Aesthetics is an issue that should be of concern to all people involved in the ultimate selection and design of a noise barrier. It is often felt to be as important as the noise reduction provided by the barrier and is the most subjective of any aspect of noise barrier design, with the phrase "beauty is in the eye of the beholder" often used in discussing noise barrier aesthetic treatments. Whether a jagged, stepped, sloped, uniform, non-uniform, colored, plain, straight, curved, or textured barrier is desired at any given location is a decision left to the responsible organization based on its policies and procedures regarding design philosophies, community input, and any other factors which are considered in the decision making process related to barrier aesthetics. Public input should always by considered in the aesthetic design of noise barriers. The intent of this section is not to justify any particular philosophy related to any element of aesthetic design, but rather to discuss elements that should be considered regardless of the particular aesthetic philosophy chosen.

In designing noise barriers, there are two general approaches or philosophies related to aesthetic treatments. One philosophy is to aesthetically design the noise wall in a manner that it blends into the surrounding environment and is as unintrusive as possible. The other philosophy is to have the noise barrier be a prominent feature in the surrounding environment. Neither should be considered right or wrong in a general sense. Both philosophies have been successfully employed and even combined on the same project. In certain instances, highway sides of noise barriers have incorporated a "blend in" philosophy while community sides of the same barriers have employed more prominent architectural treatments. Certain elements of aesthetic design should be evaluated and considered separately in the design process dependent upon whether the barrier surface is being seen from the highway or from its adjacent land uses.

Prior to discussing aesthetic design issues specific to the views of the motorist (see Section 6.1.6) and the community (see Section 6.1.7), a number of aesthetic design issues common to both barrier view points are described below.

While on occasion, a barrier can be constructed at a continuously uniform distance from the roadway and at a uniform height or elevation, it is rare that barriers can be built without some change in horizontal and vertical alignment. In attempting to make aesthetically pleasing barrier transitions and profiles, barrier designers incorporate shifts and transitions into the barrier's alignment. Such changes must be made within the restrictions and tolerances of the barrier system components. For example, angles of horizontal alignment shifts on post and panel systems are restricted to those which the particular post design can accommodate. Barrier systems with cable secured, linear ball and socket style panel connections can accommodate much greater angles.

Combined shifts in both horizontal and vertical alignment (see Figure 130) can create conditions which may not be obvious to the noise barrier designer unless the barrier can be viewed from various angles. Such conditions can occur in areas where a barrier transitions from a location on the edge of shoulder of a fill section to a point at the top of a cut section (see Figure 131). The horizontal angle of the back (community) side of the barrier's transition section can actually reflect flanking sound waves back into the community which the barrier is designed to protect (see Figure 132). While such a condition cannot always be avoided, its recognition during the design process can enable the adverse condition to be rectified by placing acoustically absorptive material on the normally reflective back side.

Figure 130. Alignment changes

photo #1496

Figure 131. Alignment changes

photo #6524

Figure 132. Alignment changes: possible flanking reflections

photo #8030

Depending upon the type of barrier system utilized, vertical transitions in noise barriers can be accomplished in a variety of manners. Such transitions in post and panel systems are often accomplished by stepping the panels. A uniform appearance can be provided by designing barriers with sections containing consistently spaced equal height steps (see Figure 133). An irregular appearance can be provided by providing random height steps at irregular intervals (see Figure 134). To avoid having to cast non-rectangular panels, and for aesthetic reasons, such steps normally are made at the location of the posts. Keep in mind that on radically changing terrain, consideration should be given to sloping the bottom of the panels to avoid burying a large portion of the panels in the ground (see Figure 135). This would avoid reducing panel lengths (to ensure structural stability) and decreasing the distance between posts which would increase the number of posts required and the costs for more posts and foundations. Barrier transitions can also be accomplished using a smooth sloped top of barrier profile (see Figure 136). This technique is common with cast-in-place noise barriers. If this technique is used in a post and panel system, irregularly shaped panels are required, and consideration should be given to also sloping the post tops at a consistent angle.

Figure 133. Vertical stepping of panels: uniform

photo #6523

Figure 134. Vertical sloping of panels

Figure 135. Vertical stepping of panels: irregular

photo #111

Figure 136. Vertical sloping of panels: smooth

photo #1839

For the purpose of this discussion, caps are considered to be separate elements of the barrier system applied to either the top of noise walls or to the top of the noise wall posts. The "cap look" is accomplished as an integral part of the fabrication/construction of the noise barrier wall panels.

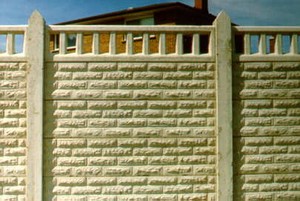

Caps have been placed on the top of noise barriers (panels, posts, or both) for both aesthetic and acoustical reasons (see Figures 137 to 140). Caps can smooth a barrier's profile eliminating saw-toothed steps and gaps and provide a pleasing shading pattern. However, care should be taken to keep the size of the cap proportional to the scale of the noise wall. Too large of a cap can give the visual perception of the noise wall being "top heavy." A cap can also interfere with the natural "washing" of the top portion of the noise wall which occurs during rain events. With the noise wall not being uniformly washed, streaking becomes more apparent over time and can become very unsightly.

Attachment and caulking details need to be carefully considered at the panel-to-post attachment points and between cap sections. Particular concern should be taken regarding the visual appearance of capped barriers which follow a meandering vertical and horizontal alignment. These conditions tend to create the potential for awkward looking barriers unless the proper care is taken in the design process.

Figure 137. Noise wall horizontal cap

photo #271

Figure 138. Noise wall horizontal cap

photo #1325

Figure 139. Noise wall horizontal cap

photo #2434

Figure 140. Noise wall horizontal cap

photo #1731

Capping of vertical posts can provide a more aesthetically pleasing barrier system but requires careful considerations in order to avoid adverse maintenance situations (see Figures 141 and 142). Capping of a steel post with a pre-manufactured cap can negate the need to provide a visually pleasing treatment on the steel post itself. However, sufficient treatment of the steel post should be provided to assure durability and reduce the likelihood of premature rusting. The design of the cap and post should be consistent with long-term maintenance anticipations. For instance, if it is necessary to remove the cap from time to time, the attachment details may be different than if the cap to post attachment is considered "permanent." In either case, drainage considerations are critical and should be considered in light of the respective cap and post materials to avoid trapping of water, resulting in premature rusting, warping, or other material degradation.

Figure 141. Noise wall vertical cap

photo #2541

Figure 142. Noise wall vertical cap

photo #5224

Several methods have been successfully used to create aesthetically pleasing treatments at the ends of noise barrier systems. Where topography permits, the barrier end can be buried into the existing ground (see Figure 143). Barriers can also be curved back away from the road at their end points. This technique may have an added advantage of providing some additional acoustical abatement of flanking noise while softening the end of the barrier (see Section 3.5.2). Ends of barriers can be reduced in height (using stepped rectangular panels as in Figure 144, or sloped panels as in Figure 145) from their acoustically required height to a height of approximately 1.5 m (5 ft), equal to right-of-way fence height. While such a treatment may provide the desired aesthetic treatment, it is likely to require construction of some area of barrier which is not absolutely necessary for acoustical reasons. Decisions related to such a treatment should weigh the added costs against the aesthetic benefits and any additional acoustical benefits provided. Ending the barrier at its required acoustical height and buffering its end points with plantings (see Figure 146) and/or berming (see Figure 147) are other techniques.

Figure 143. Barrier end treatment: buried into existing ground

photo #80

Figure 144. Barrier end treatment: stepped panel

photo #193

Figure 145. Barrier end treatment: sloped panel

photo #2385

Figure 146. Barrier end treatment: vegetation

photo #1243

Figure 147. Barrier end treatment: berming

photo #1270

Special barrier aesthetic treatments may be required in areas of cultural and/or historic significance. Often such treatments have been incorporated via special inserts, castings, or designs which reflect the historic and/or cultural characteristics of the community (see Figures 148 and 149).

Figure 148. Special considerations in cultural areas

photo #6533

Figure 149. Special considerations in historic areas

photo #6516

The view of noise barriers experienced by drivers and occupants of vehicles traveling on the highway is significantly different from the view experienced by adjacent land users. From a vehicle, a long expanse and wide viewing angle of a barrier can be seen in a very short time period. Small detail elements and textures are, therefore, less apparent from this perspective. The barrier is most often seen by the driver in a series of generally low angle views and its overall shape and patterns (the relationship of different barrier elements) becomes more apparent (see Figures 150 and 151). Issues related to the view of a noise barrier from the driver's perspective are complicated by the fact that the barrier is viewed from a different perspective by drivers traveling in one direction compared to those driving in the opposite direction.

Figure 150. View from the road

photo #2007

Figure 151. View from the road

photo #3128

The overall color of a barrier viewed from the driver's perspective becomes a major visual element. Depending upon the particular design philosophy, the chosen color can draw the eye towards the barrier (see Figure 152 and 153) or tend to blend it into the background of the surrounding terrain. In settings where trees and natural vegetation form the backdrop for the barrier, neutral to dark earthtone colors can make the barrier less obtrusive, while lighter and non-earthtone colors can make the barrier stand out. When viewed against an open backdrop such as the sky, lighter colored barriers may be less obtrusive.

Figure 152. View from the road: color

photo #3118

Figure 153. View from the road: color

photo #1218

For texture treatments on barriers to be noticeable and meaningful from the driver's perspective, they need to have fairly deep patterns and generally should be capable of creating shadow effects within the pattern itself. Aside from instances where textures are applied to create colors (such as exposed aggregate) or to deter graffiti, they provide little benefit if the design philosophy is to blend the wall into its surroundings. They can be a major element in helping to emphasizing a barrier's aesthetics if appropriately coordinated with color and pattern elements (see Figures 154 and 155).

Figure 154. View from the road: texture

photo #2368

Figure 155. View from the road: texture

photo #652

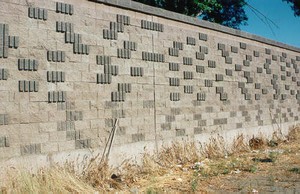

The relationship of different barrier elements (posts, panels, adjacent panels, caps, etc.) is referred to as the barrier's pattern. With the blended barrier philosophy, pattern is often de-emphasized by keeping the color and texture consistent for all barrier elements. On the other hand, the barrier's presence can be emphasized by the use of different patterns. Some examples of the wide variety of techniques used to create patterns include varying the color and/or texture of adjacent panels; providing a different color/texture on posts and/or caps than on panels; and changing the color, relief, and/or texture within the panel itself. On a long stretch of barrier, pattern (such as the occasional introduction of a non-standard panel) can help to break up the monotony of the barrier (see Figures 156 to 162).

Figure 156. View from the road: pattern

photo #1122

Figure 157. View from the road: pattern

photo #453

Figure 158. View from the road: pattern

photo #2296

Figure 159. View from the road: pattern

photo #2316

Figure 160. View from the road: pattern

photo #2352

Figure 161. View from the road: pattern

photo #328

Figure 162. View from the road: pattern

photo #5386

The shape of a noise barrier is defined by its horizontal (plan view) and vertical (profile view) configurations. A change in either the horizontal geometry or vertical profile of a noise barrier can in itself have dramatic or subtle implications in terms of the aesthetics of the barrier (see Figures 163 and 164). Similarly, the manner (uniform, non-uniform, random) in which changes in plan and elevation occur will result in either a smooth, varied, or jagged barrier shape. Barriers can be designed to meander (in plan view) and follow existing ground contours, thus creating many visually interesting configurations. Such treatments can create shapes which cast shadows, thereby giving the overall barrier a different appearance at different times of the day. Such flexibility can also enable barriers to avoid obstacles (poles, inlets, trees, etc.) that would otherwise have to be relocated or removed.

Figure 163. View from the road: shape

photo #1237

Figure 164. View from the road: shape

photo #1190

The most visible portion of the noise barrier in terms of its shape is usually its top, especially when it is viewed against a uniform backdrop such as the sky or a uniform contrasting colored background. It is for this reason that particular attention needs to be paid to the top of a barrier. Due to the types of plans and profiles typically available to individuals developing the final acoustical top of a barrier profile and the final profile in the plans, specifications, and estimate (PS&E) drawings, top of barrier profiles are often developed on drawings viewed at a right angle to the barrier (and typically the highway), and with an exaggerated horizontal scale. While an apparent desired (uniform, jagged, etc.) top of barrier profile may be developed using such plans, the actual profile (as viewed by drivers on the highway) may not meet the intent of the designer. A true profile can only be assured if one can view the barrier from the true perspective of the drivers (traveling in both directions) and from various locations along the highway. Fortunately, computer aided drafting techniques and programs, such as the Federal Highway Administration's Traffic Noise Model (FHWA TNM®), enable the designer to evaluate the barrier from such a perspective. Even after such considerations result in an acceptable top of barrier profile, the profile should be reviewed in terms of its relationship to the ground profile along the base of the barrier to assure that no unplanned awkward relationships exist.

The view of noise barriers experienced by occupants of properties behind the noise barrier (community side) is most often influenced by a relatively small, specific portion of a noise barrier system. Because of the potential closeness of such barriers to their protected receptors, the relative height of the barrier in proportion to the distance from the receptor is a factor requiring consideration. The appearance of a barrier overpowering a protected receptor by creating unwanted shadows (see Figure 165), impeding natural air flows and/or blocking panoramic views needs to be weighed against the acoustical benefits in any decision making process. Small detail elements and textures in the barrier are more easily seen and therefore are more apparent from this perspective. Since a relatively small section of the barrier is most often seen by any one observer, its overall shape and patterns are less of a factor. In general, the visual dominance of a noise barrier near residences is reduced when the barrier is placed at a distance of at least two to four times the barrier's height. Additional landscaping on the residential side may also help to reduce a barrier's visual impact ref. 18

Figure 165. View from adjacent land uses

photo #148

The overall color of a barrier viewed from the community perspective is a major visual element and the discussions in Section 6.1.6.1 pertaining to color from the roadway perspective are applicable also to the community side of the barrier (see Figure 166 and 167).

Figure 166. View from adjacent land uses: color

photo #7039

Figure 167. View from adjacent land uses: color

photo #8069

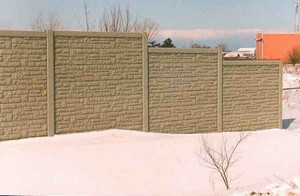

Detailed texture treatments on barriers are noticeable and meaningful when viewed from an observer in a stationary position on the community side of a noise barrier (see Figure 168). While deep textures can provide a desired look, textures of lesser relief can be successfully used in environments where the barrier is in relatively close proximity to the receptor. However, they can be a major element in helping to emphasize a barrier's aesthetics if appropriately coordinated with color and pattern elements.

Figure 168. View from adjacent land uses: texture

photo #653

As discussed in Section 6.1.6.3, pattern can play a major role in barrier aesthetics (see Figures 169 to 172). In the more confined and closely viewed community side environment, patterns need not be as bold or as large as those required along the highway side. Even if the desired philosophy tends toward uniformity of aesthetics, different community side patterns can be utilized in different areas since in many cases, only a small section of barrier is visible from any one location.

Figure 169. View from adjacent property: pattern

photo #458

Figure 170. View from adjacent property: pattern

photo #2420

Figure 171. View from adjacent property: pattern

photo #2562

Figure 172. View from adjacent property: pattern

photo #2309

While much of the discussion related to shape in Section 6.1.6.4 is also pertinent to the community side views, specific details regarding barrier plan and profile are important for the portion of the barrier seen from any particular view point. As such, horizontal shifts and top of barrier steps, slopes, and transitions, while possibly having a minor visual impact from a driver's view, can be significant from a community standpoint (see Figure 173). This is particularly noticeable where a transition (such as a step in the top of a barrier profile) or a horizontal shift occurs in the middle of a specific property. Planning such transitions to occur at property lines can in some cases minimize these types of adverse visual conditions. Since the community side of barriers is viewed from a stationary position and often from an angle perpendicular to the barrier, the need to view the barrier at shallow angles is not as critical as for the highway side.

Figure 173. View from adjacent properties: shape

photo #664

Landscaping in the vicinity of noise barriers should be integrated with the landscaping theme chosen for the general highway environment as well as being compatible with the existing landscaping (if adequate and acceptable) of the adjacent land uses and surroundings (see Figures 174 and 175). This applies whether the noise barrier is a solid wall, a berm, a combination wall and berm, or a planted barrier. Wherever possible, consideration should be given to accommodating existing vegetation in the design process. It is suggested that a field review be conducted with a landscape architect or other knowledgeable tree expert to "flag" significant trees/vegetation to avoid/saved, if practical, before the final wall alignment is set. This dictates a commitment to consider integrating the horizontal alignment of the wall with the existing topography and can have a bearing on the type of noise barrier material, the footing type, and the size of noise barrier components utilized. The vertical profile of the barrier can also be influenced by these factors. A cooperative effort balancing good engineering practice with environmental sensitivity.

Figure 174. Landscaping: integration with existing vegetation

photo #2560

Figure 175. Landscaping: integration with existing vegetation

photo #6526

In areas where the existing landscaping is sparse or not of the type deemed desirable, consideration of supplementing or replacing such vegetation with new plantings should be given. Such plantings can be in the form of trees, bushes, shrubbery, and vines placed in the vicinity of the barrier (see Figures 176 and 177). Various methods have been utilized to plant vines, which ultimately climb the barrier (see Figure 178). One method of creating a vine-covered noise barrier involves drilling angled holes through the noise barrier wall, planting vines behind the walls, and training them to grow through the holes to the highway side (see Figure 179). This method is particularly applicable in areas where space on the highway side is not available for plantings.

Figure 176.

Landscaping: supplementing vegetation

photo #1975

Figure 177.

Landscaping: supplementing vegetation

photo #6530

Figure 178.

Landscaping: supplementing vegetation

photo #470

Figure 179.

Landscaping: supplementing vegetation

photo #820

In areas where space on the highway side is available between a protective barrier (such as a Jersey barrier or steel guard rail) and the noise barrier, this area can be used for planting of vegetation, including vines (see Figures 180 and 181). In the case of a Jersey barrier, a raised planter can be created in the space between the protective barrier and the noise barrier. The type of vegetation capable of being planted and maintained in this area is dependant upon its width, soil type, irrigation (natural or artificial), orientation (full sun, shade, etc.), and climatic conditions. Even a narrow space between the noise wall and the protective barrier may be adequate to support vine growth. Such a treatment can also soften the appearance of the barrier and reduce its apparent height.

Figure 180.

photo #51

Figure 181.

photo #1759

Other specific applications where planting in the vicinity of noise barriers may be appropriate are discussed below along with other planting considerations:

While a continuous planting scheme along a barrier can be beneficial, it can also become monotonous. Occasionally breaking up this continuous planting scheme with denser plantings can add interest and create diversity. Such diversity can also be obtained by varying the species, colors, and sizes of vegetation.

It is essential that the landscape plan be coordinated with the engineering of the noise barrier and with its aesthetic design. If such coordination does not occur, situations such as the following can occur:

Figure 182. Landscaping: blocking panel aesthetic features

photo #1212

No matter how well designed a landscape plan may be from its aesthetic standpoint, it is only as good as the ability of the responsible organization to adequately maintain it. It is a waste of time and money to design an aesthetic treatment for which there is neither the commitment (in terms of manpower), the funding (long term) to adequately maintain or coordination with other maintenance considerations. Figure 183 shows a planted barrier that wasn't adequately watered. Figure 184 shows a barrier with a stain applied around the vine growth causing unstained patches on the wall; the landscapers should have coordinated the timing of their plantings with the maintenance personnel assigned to stain the wall. No matter what the desire from an aesthetic standpoint, the landscape plan needs to be responsive to these constraints. Such constraints may appropriately lead to the selection of vegetation that is native "maintenance free" and to a plan that will foster growth of natural vegetation.

Figure 183. Landscaping: consistency with maintenance philosophy

photo #6531

Figure 184. Landscaping: consistency with maintenance philosophy

photo #2155

|

Aesthetic considerations for all noise barriers. |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item# | Main Topic | Sub-Topic | Consideration | See Also Section |

| 6-1 | Alignment Changes | Acoustical | Shifts and transitions into the barrier's alignment must be made within the restrictions and tolerances of the barrier system components. Combined shifts in both horizontal and vertical alignment must avoid reflecting flanking sound waves back into the community. | 6.1.1 |

| 6-2 | Vertical Stepping/ Sloping of Panels | Aesthetic | To avoid having to cast non-rectangular panels, stepping of panels should be made at the location of the posts with consideration also given to sloping the post tops at a consistent angle. | 6.1.2 |

| 6-3 | Caps | Aesthetic | Consider the aesthetic concerns related to the size of the cap in proportion to the scale of the noise wall and related to the horizontal and vertical alignment of the cap with the entire barrier. | 6.1.3 |

| Drainage and Utility | Provide for adequate drainage requirements. | 6.1.3 | ||

| Structural | Attachment and caulking details need to be carefully considered at the panel-to-post attachment points and between cap sections. | 6.1.3 | ||

| Maintenance | Barriers with large horizontal caps may shade the top portion of a barrier and prevent the natural cleansing of that area by rain water. | 6.1.3 | ||

| 6-4 | Barrier Ends | Cost | When considering a barrier end treatment, the decision should weigh costs against any acoustical and/or aesthetic reasons. | 6.1.4 |

| 6-5 | View from the Road | . | Small detail elements and textures are less apparent from this perspective. The barrier is seen from low angle views, and its overall shape and patterns become more apparent. Also note the different perspective of drivers traveling in opposite directions. | 6.1.6 |

| 6-6 | View from Adjacent Land Uses | . | Because of the potential closeness of barriers, the relative height of the barrier in proportion to the distance from the receptor is a factor requiring consideration. Horizontal shifts and top of barrier steps, slopes and transitions property boundaries require planning to minimize adverse visual conditions. | 6.1.7 |

| 6-7 | Landscaping | Aesthetic | Trees, high scrubs, and vines could hide aesthetic inserts, designs cast in noise barriers, or other specifically designed aesthetic features of the noise barriers. | 6.1.7 |

| Drainage and Utility | Drainage under, along, or through the noise barrier could be affected by landscaping placed in inappropriate locations. | 6.1.7 | ||

| Safety | Plantings could restrict access through barrier overlap areas, to access doors or fire hose valves, or to the noise barrier itself. Plantings could also obscure the identification signs for these access features. | 6.1.7 | ||

| Litter | Landscaping in a high litter area should also consider what type of vegetation is best to use. A thorny type of bush may make litter cleanup more difficult than such litter removal from a grassy area. | 12.7 |