The objective of this chapter is to provide an understanding of:

As mentioned in Chapter 2, P3s are generally financed by a combination of debt and equity. These are broad categories, and there may be several variations on each type of financing, such as short-term debt, long-term debt, subordinate debt, preferred equity, common equity, and mezzanine financing. The risk appetite and associated pricing for different types of financing are displayed in Figure 7. This figure is only indicative. The financing term or repayment period (tenor) and pricing may differ depending on timing and other project characteristics. In addition, P3s also frequently receive upfront subsidies or grants and milestone payments from public authorities. Although both upfront grants and milestone payments may be funded by the public authority from the same revenue source, the latter are conditioned upon the P3 developer achieving certain pre-defined project completion indicators. Subsidies may reduce the amount of financing required for a project, close a financing gap or help to lower required tolls or availability payments. Financing costs can be reduced through the use of credit enhancements. These include internal credit enhancements such as cash reserves, and various types of external credit enhancements such as bond insurance. Finally, all of these elements need to be combined in a strategic fashion to optimize project delivery.

Figure 7. Types of Financing with Notional Rate and Tenor

View larger version of Figure 7

Debt plays a critical role in P3 projects. The project finance model is designed to be highly leveraged, meaning that debt - as opposed to equity - typically provides more than half of the financing required for the project. The level of debt in a project is a direct function of the project's level of risk. This attribute of the project is sometimes referred to as "gearing" and is measured by the project's debt/equity ratio. Projects with a low level of risk may be very highly leveraged, reaching as much as 90 percent debt and 10 percent equity, or 90/10. Riskier projects will require more equity financing and may feature debt/equity ratios in the range of 70/30 or 60/40. The level of debt in a particular project finance structure is dictated by the debt providers.

As a general rule, it can be said that debt providers are more conservative and risk-averse than equity investors. Debt providers accept lower returns, but only on the condition that loan repayment is predictable and involves less risk. Indeed, repayment of debt, at least senior debt, is a contractual requirement codified in the bond indenture or loan agreement. Equity returns, on the other hand, may have target rates but typically are not contractually obligated. There are two main financial products used for debt financing: bonds and loans. These may come as both senior and subordinate sources of financing. These different types of debt are described below.

There are two main types of debt often used to finance P3 projects: senior and subordinate. These designations generally describe the priority of the creditor relative to other creditors with regard to two things - payments from the project (when the project is not in default) and security (after a project has defaulted). So, for example, we have talked about the cash flow waterfall that is typical in P3 financing. The waterfall describes the priority order in which payments are applied to different project needs - paying operating expenses, establishing reserves, repaying creditors, rewarding equity investors, etc. Senior debt providers receive their payments from the project cash flow before any other capital provider, helping to ensure that they are paid in full and on time even if there may not be sufficient cash to pay a creditor lower in the order, or subordinate. For this relatively secure position, the creditor will be paid a lower return than a subordinate creditor.

Similarly, there is a priority of access to project collateral among the creditors if a default occurs. In a typical P3 project financing, a variety of assets will be used to provide security to creditors - real property (physical facilities and fixtures, and possibly land) as well as personal property (equipment, vehicles, intellectual property, and the project license itself). With first priority access, the senior debt providers are assured to be first in line to step into the shoes of the project operator, or under liquidation to receive the first proceeds of sale of any property, helping to minimize losses in that event.

One feature that defines senior debt is its coverage ratio. Annual debt service coverage ratios (ADSCR) are a critical indicator for all project financings. From one perspective, they are an indicator of the financial condition of the project. From another perspective, minimum ADSCRs are a requirement of debt providers, who will require higher ADSCRs for projects with higher levels of perceived risk. The ratio requires the net cash flow available for debt service (CFADS) from operations in any year to exceed the debt service due in that year. Cash balances at the beginning of the fiscal period are not taken into account as "cash" for the purposes of this test. All cash flows completely through the waterfall each year. As a practical matter there will be minimal cash on hand that has not been trapped by reserves or distributed to equity accounts. As the cash flow waterfall indicates, only operating expenses are higher than debt service in order of priority, so once those are deducted from revenue, the difference is CFADS. 14 The DSCR is calculated by dividing CFADS by debt service (DS), as shown in figure 8:

Figure 8. Equation. Calculation of DSCR

| DSCR = | CFADS |

| DS |

Where

DSCR = Debt Service Coverage Ratio

CFADS = Cash Flow Available for Debt Service

DS = Debt Service (Principal + Interest)

Availability payments provide a high certainty of cash flows so that the need for cash flows to exceed debt service is kept to a minimum. Availability payment deals with a AAA-rated government may be eligible for a minimum ADSCR of 1.2 or lower, whereas projects with significant toll revenue risk may require an ADSCR of 2.0 or higher for senior debt. This requires CFADS to be double the debt service for the specified year, which allows for a substantial shortfall in estimated traffic perhaps resulting from toll price elasticity well outside the expected range. Cash balances in reserve accounts and any other cash on hand are not treated as available in this measure of the project company's ability to repay debt.

The ADSCR determines the maximum amount of debt a project can use for financing (debt capacity). If cash flows only support a 2.0 ADSCR with 70 percent debt financing, then more senior debt cannot be issued to finance the project. If initial modeling determines high projected DSCRs, there may be room either for additional senior debt or for subordinate debt. Subordinate debt requires lower coverage ratios than senior debt and is lower in the priority of payments than senior debt. In exchange for this riskier position, subordinate debt typically requires higher rates. Subordinate debt is discussed in more detail in section 3.1.2.

Once a project is built, the ADSCR is also used to determine if the project can incur additional debt for capital expansion. This calculation is known as the "Additional Bonds Test" (ABT) and typically requires that an expert consultant for the project sponsor calculate ADSCR both on "historic" terms (comparing prior year's results to pro-forma existing and new debt service) and projected results (forecast indicating that ADSCR with the existing and additional debt service can be met in every future year).

Project lenders also monitor the loan life coverage ratio (LLCR). LLCR considers the ratio of the present value of total cash flow available over the life of the loan (discounted at the loan interest rate) to the face amount borrowed. Unlike the ADSCR, the LLCR does not consider each year's coverage factor; rather, it considers the extent to which the NPV of cash flows anticipated by the loan's stated maturity date are sufficient to retire the remaining principal outstanding. The minimum initial LLCR requirement for a P3 project typically requires discounted future cash flows to meet a test about 10 percent higher than required by the ADSCR. Cash balances in reserve accounts that are not earmarked for maintenance purposes can be included in this measure of the project company's ability to repay debt. Finally there is a project life coverage ratio (PLCR), which takes into account the NPV of project cash flows over the life of the project -- effectively, the term of the P3 operating concession, which may extend well beyond the loan's final maturity date. See "Debt Tail Requirements" discussion below.

To hedge against the risk of negative project performance, debt providers usually require a schedule of repayment that is shorter than the concession term, thus creating a debt repayment tail (see Figure 9). Tails will be longer for riskier projects, particularly those for which the private partner accepts demand risk, such as toll roads. By this feature, the public authority provides an additional period for the debt providers to recover their principal in cases when the debt or the project is restructured. Under availability payment deals, the tail typically is very short. In Canada, for example, tails on availability projects are typically set at 6 months because availability payments are typically calculated to include debt service payments.

Figure 9. Illustrative Project Costs, Forecast Revenues, Expenses, and Debt Service

View larger version of Figure 9

Some countries have experimented with flexible-term concessions to hedge against revenue risk. The term of these projects varies with pre-determined indicators, such as principal repayment, revenue generation and traffic volume targets or cumulative and discounted revenue targets 15. Under a "Present Value of Revenues (PVR)" criterion, Developers propose the minimum gross revenue (discounted at a common rate) they are willing to accept. The P3 contract ends when the gross revenue PV is reached. The concession term may vary, but the contract provides for a base case and minimum/maximum terms. The mechanism transfers most revenue risk to the Agency, without immediate fiscal impacts. This makes it attractive from financeability and fiscal impact perspectives.

Tax-exempt bonds are instruments that are issued to investors in the capital markets. Although these instruments are often referred to as "municipal bonds" in US market jargon, they include debt instruments issued by both state and local governments. These bonds are issued to finance the vast majority of infrastructure in the US, including transportation infrastructure, and this has been the norm for more than 150 years. In fact, the US municipal bond market is unique globally in the access to capital markets that it provides state and local governments and their agencies.

State and local government bonds are tax-exempt in that taxpayers holding such bonds are allowed to exclude their interest earnings on such instruments from gross income for purposes of determining their Federal income tax liability. Since investors do not have to pay tax on their interest income from these instruments, they do not require as high a return as they might with so-called taxable debt instruments, such as corporate bonds. Tax-exempt state and local government bonds usually offer a lower interest rate than even US Treasury bonds, since US Treasury bonds are not tax-exempt. If the creditworthiness of the US Treasury and a state/local government bond issuer were equal, the rate offered by the tax-exempt bond theoretically should be equal to one minus the tax rate multiplied by the Treasury rate. Tax rates differ among individuals, but assuming the maximum marginal tax rate of 35%, the comparable tax-exempt rate would be 65 percent of the rate offered by Treasury bonds: (1-t)r with t=0.35. As a practical matter, other factors such as liquidity differences and call features require tax-exempt bonds to pay higher yields to investors than this equation would suggest. There may be additional tax exemptions available at the state and local level. However, during the financial crisis beginning in 2008, rates on state and local government bonds increased to levels much higher than those of US Treasury bonds, due to concerns about the fiscal stability of municipal issuers. Figure 10 shows the ratio of the benchmark state and local government bond rate to the benchmark US Treasury bond rate during this period.

Figure 10. Ratio of Tax-exempt Bond Yield to Treasury Yield

View larger version of Figure 10

The tax-exemption provided by the Federal government for state and local government bonds is generally applicable only where the state or local government unit is the main party benefitting from the project and its financing. Generally, within the transportation P3 market, no more than 10 percent of an issuance of tax-exempt bonds can benefit any private business. If that threshold is exceeded, the bonds will lose their tax-exempt status. (PABs are an exception, and they are discussed in greater detail later in this chapter.) State and local governments may also use tax-exempt bonds to raise funds that are in turn committed to P3s in the form of an upfront grant. For example, Virginia DOT used Federal Grant Anticipation Revenue Vehicle (GARVEE) bonds to raise its upfront grant for the Midtown Tunnel project. With GARVEE bonds, future Federal funds are used to repay the debt and related financing costs under the provisions of Section 122 of Title 23, U.S. Code. GARVEEs can be issued by a state, a political subdivision of a state, or a public authority.

Approximately two-thirds of all tax-exempt bonds are issued as "revenue bonds," meaning their repayment comes from a designated revenue source. In some cases, the revenue source is an operating enterprise such as a toll road or water and sewer system, where debt service is paid from net revenues derived from users, after paying operations and maintenance costs. In other cases (often termed "special revenue bonds"), the revenue source is a dedicated tax or fee unrelated to the performance of the enterprise. For example, many state transportation departments issue special revenue bonds secured by statewide fuel taxes, and public transportation agencies issue bonds secured by county or regional sales taxes. Such bonds typically have a "gross" rather than "net" pledge of the dedicated revenues and these revenues are generally not subject to project-related risks, making them more secure than project-based financings.

Revenue bonds are distinguished from "general obligation" bonds that are backed by the "full faith and credit" of their issuers - that is, by the issuer's taxing power. Enterprise-backed revenue bonds can in fact be viewed as a form of project finance since specific revenue streams are designated as the source of repayment, including toll roads and other infrastructure user fees. Revenue bonds may offer public authorities a type of non-recourse financing, as bondholders cannot typically pursue repayment of revenue bonds from general government revenues unless the public authority has offered a guarantee or backstop for a specific financing. Project revenue bonds typically bear higher interest rates than their general obligation equivalents, since their revenue sources are more limited and thus represent a higher risk to the bondholder.

Where tax-exempt revenue bonds differ from the debt used in most P3 financings is in the prioritization of payments. Bonds may be issued on the basis of gross revenue pledges or net revenue pledges. General Obligation bonds are gross revenue pledges; so bondholders have the most senior claim on the revenues of the bond issuers and are in the top position in terms of the cash flow waterfall or flow of funds. Most tax-backed revenue bonds, such as those backed by gasoline tax revenues, also are gross revenue pledges. Operating revenue bonds, such as toll revenue bonds, are often net revenue pledges so debt service payment on the bonds is second to operating expenses and major maintenance costs. However, this is not always the case. Recent examples of gross revenue pledges for toll financings include Triangle Expressway in North Carolina, Grand Parkway in Texas and the Louisville-Southern Indiana Ohio River Bridges Project. Where tax-exempt revenue bond financings are based on net revenues, the public authority may offer a guarantee of O&M expenses, so the project is not truly "ring-fenced." (See Triangle Expressway case study in Appendix B.)

The particular sectors that may be financed tax-exempt with PABs under applicable tax law tend to be situations where private capital has traditionally been active, or where private parties have been heavily engaged in operation and management of the facilities. Even then, the physical facilities are typically required to be owned by the governmental unit, and if leased to a private entity for operations, then subject to certain terms ensuring that the indicia of tax ownership remain with the public authority. In transportation, these facilities include what are referred to in the Tax Code as "exempt facilities" - airports, ports, local mass transit, high-speed intercity rail, and qualified highway or surface freight transfer facilities.

For surface transportation projects, PAB allocations are available from a $15 billion pool established by the 2005 Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for Users (SAFETEA-LU). As of December 2015, approximately $12 billion of this pool had been allocated and $4.8 billion issued. Table 5 indicates which projects have received allocations and issued bonds through 2015. More information on the PAB allocation process is available on the FHWA website at: https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ipd/finance/tools_programs/federal_debt_financing/private_activity_bonds/.

| Project | PAB Allocation ($ in thousands) |

|---|---|

| Bonds Issued | |

| Capital Beltway HOT Lanes, Northern Virginia | $589,000 |

| North Tarrant Express, Fort Worth, Texas | $400,000 |

| IH 635 Managed Lanes (LBJ Freeway), Dallas, Texas | $615,000 |

| RTD Eagle Project (East Corridor & Gold Line), Denver, Colorado | $397,835 |

| CenterPoint Intermodal Center, Joliet, Illinois | $150,000 |

| CenterPoint Intermodal Center, Joliet, Illinois | $75,000 |

| Downtown Tunnel/Midtown Tunnel/MLK Extension, Norfolk, Virginia | $675,004 |

| I-95 HOV/HOT Lanes, Northern Virginia | $252,648 |

| Ohio River Bridges East End Crossing, Louisville, Kentucky | $676,805 |

| North Tarrant Express Segments 3A & 3B, Fort Worth, Texas | $274,030 |

| Goethals Bridge, Staten Island, New York | $460,915 |

| U.S.36 Managed Lanes/BRT Phase 2, Denver Metro Area, Colorado | $20,360 |

| I-69 Section 5, Bloomington to Martinsville, Indiana | $243,845 |

| Rapid Bridge Replacement Program, Pennsylvania | $721,485 |

| Portsmouth Bypass, Ohio | $227,355 |

| I-77 Managed Lanes, North Carolina | $100,000 |

| Subtotal | $5,879,282 |

| Allocations | |

| Knik Arm Crossing, Anchorage, Alaska | $600,000 |

| CenterPoint Intermodal Center, Joliet, Illinois | $700,000 |

| SH-288, Houston Metro Area, Texas | $600,000 |

| Purple Line, Maryland | $1,300,000 |

| Rapid Bridge Replacement Program, Pennsylvania | $1,200,000 |

| Purple Line, Maryland | $1,300,000 |

| All Aboard Florida | $1,750,000 |

| I-70 East Reconstruction, Colorado | $725,000 |

| Subtotal | $5,675,000 |

| GRAND TOTAL | $11,554,282 |

P3 bank loans are made directly by commercial banks and held on bank balance sheets. Large loans may be syndicated to spread the risk over several banks. Projects may therefore be financed by a group, or club, of banks. For large-scale projects, "club deals" may involve 10 or more banks. The original financing for the I-595 project in Florida featured a 10-year, $800 million bank club loan. The consortium of banks included BBVA, Caja Madrid, Calyon, Fortis, Societe Generale and Santander. One reason cited for the use of bank financing for the I-595 and Port of Miami Tunnel projects was the turmoil in the bond market in the first half of 2009 when both of these projects reached financial close.

Bank loans offer some major advantages compared to bonds. Banks are willing to advance funds, often in small amounts, during a flexible drawdown period. In contrast, bond issues sold in the capital markets generally are issued in the full amount of the debt capital required for the project, both for reasons of efficiency and to avoid market risk of not being able to complete the capital raise. As a consequence, part of the funding will likely be placed on deposit at a lower interest rate than that the project has to pay to bondholders. This interest rate differential is known as negative carry and is an additional cost that partly offsets the lower coupon on bond financing.

Compared to bonds, bank loan tenors on P3s since the financial crisis have been much shorter. Recent examples are provided in section 3.5. This partly results from the weakened financial health of the banks, which all suffered from the financial crisis. Another factor is increased bank regulation that requires banks to hold additional capital against long-term loans. This is a requirement of both the US Dodd-Frank financial legislation and the Basel III international bank regulatory regime. The net stable funding ratio requirement of Basel III requires banks to obtain additional long-term deposits, which are more expensive, when making long-term loans. P3 project loans are also not considered liquid under Basel III solvency tests, again driving up the cost of bank finance. A study by the UK National Audit Office after the banking crisis found that the cost of bank loans for P3 projects had risen by around one-third.

An interest rate swap is a contractual agreement whereby two parties agree to exchange payments on a predetermined notional amount(s) over a predetermined set of time at agreed upon interest rate(s). Typically, one party will receive the floating rate payments in exchange for paying a fixed rate. Typically, there is a "netting" of the two payments, with one party receiving the net payments in each period. There is no exchange of principal, only an exchange in interest rate payments usually settled in net dollar amounts.

Interest rate swaps are common in bank-financed deals since banks usually lend at variable rates, which borrowers then swap for a set of payments based on a fixed rate. Prior to the 2008 financial crisis, some municipal issuers issued variable rate bonds and entered into an interest rate swap with a financial institution to obtain a "synthetic" fixed rate slightly below their direct fixed rate borrowing cost. In the current regulatory and interest rate environment, swaps are not common in bond-financed US P3 projects, and most bonds used to finance these projects carry a fixed interest rate or coupon.

Subordinate debt requires lower DSCRs than senior debt but higher interest rates to compensate for its lower position in the cash flow waterfall. Subordinate debt may be provided by specialized funds or by project shareholders. TIFIA, the USDOT financing program, also is authorized to provide functionally subordinate debt.

Shareholder loans and mezzanine financing are sometimes provided by investors to satisfy project financing needs and enhance their own returns. These lending instruments offer the benefits of loans in that they pay a predetermined rate on a contractual basis. The interest on these loans is also deducted from the project company's taxable income. These loans typically carry a higher interest rate than senior debt but a lower rate than targeted equity returns.

The East End Crossing Project provides an example of shareholder loans during the construction phase on a US P3 project. The loans are referred to as equity bridge loans, and the principal of the loan is converted to equity at substantial completion.

The TIFIA program provides credit for qualified projects of regional and national significance. Many surface transportation projects - highway, transit, railroad, intermodal freight, and port access - are eligible to apply for assistance. At the time of writing, since its launch in 1998, the TIFIA program has helped 56 projects leverage nearly $23 billion in DOT credit assistance into more than $82.5 billion in infrastructure investment across the U.S.

The program nominally offers three distinct types of financial assistance - direct loans, loan guarantees, and standby lines of credits. These instruments are designed to address the varying requirements of projects throughout their lifecycles.

As a practical matter, however, virtually all of the TIFIA activity has taken the form of direct loans, because they offer the most cost-effective form of credit assistance. To be eligible for assistance, project costs generally must total at least $50 million ($15 million for Intelligent Transportation System projects and $10 million for transit-oriented development projects, rural projects and local infrastructure projects). TIFIA generally finances up to 33 percent of eligible costs but cannot lend more than 49 percent of eligible project costs.

The TIFIA Program is designed to fill market gaps and leverage substantial private co-investment by providing supplemental and subordinate capital to projects. TIFIA credit assistance provides improved access to capital markets, flexible repayment terms, and potentially more favorable interest rates than can be found in private capital markets for similar instruments. Additionally, TIFIA can help advance qualified, large-scale projects that otherwise might be delayed or deferred because of size, complexity, or uncertainty over the timing of revenues.

The TIFIA program has been vital to the development of the US P3 industry. TIFIA has been involved in almost all major US greenfield projects advanced as P3, and approximately one-third of the projects in the TIFIA portfolio are P3 projects. Some of TIFIA's P3 projects include Capital Beltway HOT Lanes, Port of Miami Tunnel, North Tarrant Express, Presidio Parkway, and Goethals Bridge (see Table 6).

| Project | Amount | Rate (%) | Term (years)* |

|---|---|---|---|

| I-95 HOT Lanes | $300.0 | 2.76 | 35.0 |

| Presidio Parkway Tranche A | $90.0 | 0.46 | 3.5 |

| Presidio Parkway Tranche B | $60.0 | 2.71 | 28.0 |

| Midtown Tunnel | $422.0 | 3.17 | 44.0 |

| LBJ-635 Corridor | $850.0 | 4.22 | 40.5 |

| North Tarrant Express | $650.0 | 4.51 | 35.0 |

| Port of Miami Tunnel | $341.5 | 4.31 | 35.0 |

| I-595 | $603.4 | 3.63 | 35.0 |

| SH-130 Segment V-VI | $430.0 | 4.45 | 35.0 |

| I-495 HOT Lanes | $588.9 | 4.4 | 40.0 |

| Source: State and Local Government Series (SLGS)

Daily Rate *Term is estimated from data at financial close. All loans mature no later than 35 years after Substantial Completion. TIFIA rate is set according to comparable-term Treasury yields. Source: https://www.transportation.gov/tifia/projects-financed |

|||

The TIFIA program has developed a tailored approach for credit evaluations of P3 projects to facilitate these procurements. To align the TIFIA evaluation process with the overall P3 procurement timeframe, the program gets involved early in the application process. This is intended to give both the public sponsor and private bidders greater cost certainty and to streamline the TIFIA review process once the selected private bidder submits the plan of finance.

This section explores the contribution that equity investors make to a P3 project, and how to evaluate the investment returns set out in the project's financial plan.

Equity investors seek to maximize their risk-adjusted returns within their investment parameters and risk profile. They do this by minimizing costs and risks. This makes them efficient managers and owners of projects. In this sense, equity investor goals are generally aligned with government clients on P3 projects. However, in some cases goals may diverge. Most equity investors who invest at the initiation of the project have a short-term horizon of 10 years or less. To ensure "skin in the game," design-build subcontractors generally are required to hold equity in P3 projects at least until construction is complete and the project is operational. Public authorities and other equity investors may require O&M subcontractors to keep equity invested in projects during the entire contract term. Different types of equity investors are discussed in more detail below.

Another strategy for equity investors to amplify their returns is to maximize leverage, or the debt/equity ratio. Increasing the level of debt financing on a project creates a higher return on a lower amount of equity invested, although it may also increase financial risks. The debt/equity ratio usually is determined by requirements of the debt providers, mainly the debt service coverage ratio (DSCR), discussed above in Section 3.1.1.

On projects with terms much longer than the debt used to finance them, equity investors look forward to the last phase of the project when all debt has been paid down, since more cash flows are then available to be paid out as dividends. In other cases, equity investors prefer to increase leverage to have more equity available for other investments. This is often the case in asset monetization, where the initial acquisition may be done using all equity, only to be leveraged after acquisition.

Equity investors are considered to be in a first-loss position and to accept the highest level of risk among sources of financing. They appear at the bottom of the cash flow waterfall. While equity investors may have target rates of return, the amount and timing of their returns are uncertain. This is the main difference between debt and equity financing. Debt providers enter into contracts to provide upfront financing and be repaid at predetermined rates and times over the course of a designated term. Equity investors take the risk and reward of being business owners. Just like investors in the stock market, equity investors may lose their entire investment without recourse. Because of this high level of risk to equity investments, equity investors require a higher return on their investments.

While equity investors are in a first-loss position, they also seek to insulate themselves from losses and to transfer risks, just like debt providers and public authorities. Major risks can be passed on to sub-contractors, up to negotiated financial limits.

Public authorities can benefit from the incentive framework in which equity investors operate. For example, equity investors will seek to minimize costs. However, public authorities need to ensure that their interests are aligned with equity investors in terms of project outcomes. That is the rationale behind the performance requirements and other contract issues discussed in chapter 2.

Equity investors in transportation P3 projects fall into three main categories, as described below:

Table 7 shows the equity investors and the amount invested for recent P3 transportation projects in the US.

| Project/Investor | Amount (millions) |

|---|---|

| East End Crossing | |

| Walsh Investors | $26.00 |

| VINCI Concessions SAS | $26.00 |

| Bilfinger Berger | $26.00 |

| I-95 HOT Lanes | |

| Fluor | $24.20 |

| DRIVe USA | $217.80 |

| Presidio Parkway | |

| Hochtief | $23.00 |

| Meridiam | $23.00 |

| Midtown Tunnel | |

| Skanska | $99.45 |

| Macquarie | $121.55 |

| LBJ-635 Corridor | |

| Cintra | $364.00 |

| Meridiam | $266.00 |

| Dallas Police / Fire Pension Fund | $70.00 |

| North Tarrant Express | |

| Cintra | $241.50 |

| Meridiam | $141.90 |

| Dallas Police / Fire Pension Fund | $42.60 |

| Port of Miami Tunnel | |

| Bouygues | $8.00 |

| Meridiam | $72.30 |

| I-595 | |

| ACS Iridium | $207.70 |

| SH-130 Segment V-VI | |

| Cintra | $136.40 |

| Zachry | $73.40 |

| I-495 HOT Lanes | |

| Flour | $35.00 |

| Transurban | $315.00 |

| Source: 2013 Guide to US P3 Transportation Projects published by Claret Consulting and available at http://ww25.doobymedia.com/2013-guide-to-us-p3-transportation-projects-semiannual-update-july-2013/. | |

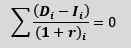

The minimum rate of return required by investors is also known as a hurdle rate. The hurdle rates used by investors to determine their bid price do not necessarily reveal their expected returns. The bid rate is likely to be an IRR on equity calculated using the equation presented in Figure 11. 16

Figure 11. Calculation of Bid Rate

|

Where r = Internal Rate of Return (Bid Rate). Di = Dividend at Year i. Ii= Amount Invested by the Shareholders at Year i. |

For an investment to be justified, and if held to the targeted investment horizon, the equity IRR must be above the hurdle rate. The approach used by bidders for pricing P3 projects is to determine the leverage and cost of debt, and then to apply their required equity return to the balance of funding needed. The required equity IRR (i.e., the hurdle rate) may then be used by bidders, under a number of different scenarios, to calculate the required annual availability payment or to set the target level of revenues from tolls.

Actual returns may turn out higher than expected because of operating efficiency, or because of changes from the assumptions made in the original project model. For example, if the rate of increase in operating costs is overestimated, and the rate of increase in revenues is underestimated, the resulting trends will increasingly diverge, and profitability will be boosted. Figure 12 shows the case of O&M costs increasing at 2.5 percent and revenues increasing at 3.5 percent. The result is an 1 increase in the net revenue from 20 percent in Year 1 to 50 percent in Year 50.

Figure 12. Revenues Trending Higher than Costs

View larger version of Figure 12

This example shows the importance of the initial choice of cost indices in forecasting growth in revenues and expenses. For example, the national CPI is a composite and may be easier to hold the growth in expenses below CPI in some regions of the country than in others.

Required equity returns decrease as the risks affecting returns reduce over time. Table 8 illustrates such a reduction, as a project moves through key phases. These differentials in required returns exist even though the investors pass most project delivery risks to their contractors (mainly on fixed priced contract terms).

| Phase | Risk-free Rate, percent | Project Risk, percent | Phase Risk, percent | Equity Return, percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construction | 6 | 2 to 4 | 4 | 12 to 14 |

| Ramp up | 6 | 2 to 4 | 2 | 10 to 12 |

| Long-term operation | 6 | 2 to 4 | - | 8 to 10 |

| Source: Adapted from Yescombe, E.R. (2007) Public-Private Partnerships: Principles of Policy and Finance. Oxford UK: Elsevier Ltd. | ||||

The risks also vary depending on differences in construction risk, such as if difficult tunneling is involved, and if applicable, the level of revenue risk on traffic volume and toll pricing. As further discussed in section 3.2.5, the investors may bear substantial revenue risk, which could be mitigated by dynamic concession terms and/or revenue bands. Table 9 indicates the targeted post-tax equity IRRs for 10 recent transportation P3 projects in the U.S.

The project IRR represents the financial return or yield of the project regardless of the financing structure. It may be used to assess the general financial viability of a project without taking account of its financial structure (i.e., ratio of debt to equity). The equity IRR generally will be higher than the project IRR. One way to understand this is to realize that the project IRR must be distributed to several parties, mainly tax authorities, debt providers, and equity investors. Project IRR can be presented in both pre-tax and post-tax forms. As discussed above, debt is typically cheaper than equity and, since P3s are typically highly leveraged, debt typically accounts for more than half of project financing. So, equity is both more expensive (equity investors expect a higher return) and less abundant in project financing. In other words, more of the project return will accrue to a smaller amount of the financing.

An inherent factor, potentially generating higher returns than declared in the bid, is the initial investors' expected exit rate of return (i.e., the return from selling the project to a new investor prior to the end of the concession). At the time of bidding, primary investors can estimate a future value of their equity, based on pro-forma projections of financial performance or recent secondary market prices. When based on availability payments, revenue streams are relatively stable and can confidently be estimated within a narrow range. Transportation projects with traffic risk will naturally produce revenue estimates across a broader range. In either case, investors also have to consider economic factors that may alter the required rate of return by the time their project is ready for sale.

In the UK, for example, secondary market investors have acquired revenue streams from many projects that have reached the operating stage. These have been availability payment based projects, and the required returns have recently been around 7 to 8.5 percent. The impact on UK projects initially bid at around 14 to 15 percent has been to generate exit rates of return above 30 percent. Potential returns on this scale have attracted investors during the uncertain bidding stages of transportation projects, leading to increased competition.

The secondary market for equity stakes in P3 projects in the US is nascent. There have been a few transactions, most involving the outright sale of the project to another developer/owner. The exception is ACS's sale of half of its stake in the I-595 project to the Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association College Retirement Equities Fund (TIAA-CREF) in October 2011. The project was still under construction at the time, and the sale was seen mainly as a move by ACS to shore up its balance sheet given financial difficulties in its home market of Spain and in other regions. Other examples of P3 project sales include the following:

Many transportation projects have, in some respects, been "repeat" projects where the format and risks of the type of project have become well understood. Although the P3 contract structure pushes risk down to the subcontractors best able to manage them, there are still long-term performance, coordination and "systematic" risks (sometimes referred to as "systemic" risks) related to the overall economy that help to justify equity rates of return. Risks that may require a higher return, but which reduce over time include the following:

The FHWA's Risk Assessment Guidebook suggests that some systematic risk may be valued through a derived discount rate, and some risk may be valued in the cash flows.

FHWA Risk Assessment Guidebook, Appendix 2, Determination of the Discount Rate

In a P3 approach, a substantial portion of the risk profile is reflected in the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC). The pricing follows the organizational structure of a P3 special purpose vehicle (SPV). Most of the risks are typically subcontracted and therefore shown in the cash flows in the bid. Some of the risks are explicitly or implicitly (for example through caps on liabilities in subcontracts) retained by the SPV. These are not only typical systematic risk categories (for example inflation, interest rate, and toll risk) but also risk categories that are associated with the long-term and integrated characteristics of the contract (long-term performance risk and project coordination risks).

Projects are structured so that debt service payments can be met by project income under various risk-based scenarios. On availability payment based projects, debt providers have low default risk as a result of the credit being a relatively safe public authority. This reduces the project risk and lowers the cost of finance. The amount of equity required will likely fall in the range of 5 to 15 percent. There is a more variable risk of public authority interference - for example, managing a P3 project more aggressively after a change of political leadership. In early credit rating exercises, availability payment projects were ranked two notches below the public authority payment counterparty.

Investors in a toll-based project may bear substantial revenue risk, which may be mitigated by dynamic concession terms and/or revenue bands. The amount of equity required may be higher, reaching 20 to 40 percent of the total funding needed. As table 10 indicates, US P3 projects reflect these realities. The toll concession projects have featured equity investments that represent 16 to 35 percent of the financing, while equity in availability payment projects has ranged from 10 to 13 percent.

A key feature of US P3 toll concession projects has been relatively large state grants to help cover capital costs (see Table 10). In addition to grants, projects may also receive milestone payments, which are conditioned upon the developer achieving certain project completion thresholds. The choice of whether to provide funding through upfront public subsidies or through milestone payments may be determined by a state's own cash flow issues or strategically through consideration of financial incentives. These issues are addressed in more detail in section 3.6. State grants help to reduce required revenues to repay financing on P3 projects, which typically translates into lower toll rates on the projects.

| Project | P3 Type | Equity as a Percentage of Financing, percent | Equity as a Percentage of Cost, percent | Subsidy as a Percentage of Cost, percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I-95 HOT Lanes | Toll | 35 | 32 | 8 |

| LBJ-635 Corridor (HOT) | Toll | 31 | 25 | 19 |

| North Tarrant Expressway (HOT) | Toll | 29 | 21 | 28 |

| I-495 HOT Lanes | Toll | 23 | 18 | 21 |

| Midtown Tunnel | Toll | 17 | 11 | 15 |

| SH-130 Segment V-VI | Toll | 16 | 16 | 0 |

| Source: Official Statements, FHWA website | ||||

Operational subsidies typically have not been a feature of US P3 projects. (A recent example is I-77 in North Carolina awarded to Cintra in April 2014.) Instead, certain functions or tasks remain outside of the scope of the project, such as maintenance or policing. The project company will sometimes sub-contract the public authority for some of these services. The US market has not featured projects that are financed through a mix availability payment and user fee (toll) revenue streams, although this is a possibility and one way to provide operational subsidies even to a user-fee-based project. The UK Nottingham Express Transit Phase II project is an example of innovative structuring that does just that. The availability payment constitutes 60 percent of project revenues to start and then gradually decreases to 40 percent as other project revenues increase. The project also features performance requirements for ridership levels to encourage the private partner to attract ridership on the transit system. 17

While revenue guarantees have not been a feature of US transportation P3 projects, they have been used extensively in other countries. Some public authorities find guarantees more attractive than direct subsidies because they do not require cash commitments and are only triggered in cases when revenues do not meet projected targets. In many cases, minimum revenue guarantees (MRG) are designed in conjunction with revenue or profit sharing mechanisms. In such cases, a revenue band may be established whereby if revenues fall below a certain threshold, the public authority will pay a subsidy to the concessionaire and if revenues rise above a certain level, the concessionaire is required to share revenue with the public authority. 18

This section provides examples of loan repayment terms from both the bond market and the bank market. The public authority generally is interested in the longest available tenor for affordability reasons, to minimize the annual payment requirement even if the nominal financing rate is higher. The most desirable maturity will correspond to the useful life of a well-maintained highway. A commercial constraint on extending this period indefinitely will be the difficulty in accurately estimating future major resurfacing expenditure.

In terms of projects that have relied on bond financing, the I-95 HOT lanes project features PABs with principal payments spread out from year 18 to year 27. Repayment of the PABs for Midtown Tunnel is generally ascending, reflecting the projected increases over time in available net revenues. The LBJ-635 and North Tarrant Express PAB principal payments are spread out from year 20 to year 30. The Capital Beltway HOT Lanes PAB principal repayments are spread out from year 30 to year 40. Tenors may go even longer.

In terms of the bank market, since the onset of the financial crisis, the ability of commercial banks to extend long-term financing has been severely eroded. The SH-130 project in Texas that reached financial close early in 2008 featured a 30-year loan in the amount of $685 million. Many banks can now extend loans to a maximum of only 7 years, which is in stark contrast to long-term lending prior to the crisis. However, for I-595, the bank debt was intended to serve as long-term financing. It had an original term of 10 years with the expectation of refinancing for another 12.5 years. The allocation of refinancing risk is discussed in section 3.5.2.

For Presidio Parkway, the loan was for 3.5 years and expected to be repaid with a milestone payment. The Port of Miami Tunnel bank debt included a $322 million, 5-year loan to be repaid with $450 million of milestone and final acceptance payments and a $22 million loan to be repaid from the first availability payment.

One factor affecting bank loan tenors is the financial health of the banks, which all suffered from the financial crisis. Another factor is increased bank regulation that requires banks to hold additional capital against long-term loans. This is a requirement of both the US Dodd-Frank financial legislation and the Basel III international bank regulatory regime.

Both bank and bond financing allow for "repayment sculpting" to match debt service to project revenues. Bond financing usually features the issuance of a series of bonds that carry different maturities and rates. Midtown Tunnel relies on $663,750,000 of PABs as part of its financing. This amount is divided into 14 separate bond maturities or tranches (11 serial bonds and 3 term bonds) that are scheduled to come due within a range of 10 to 30 years. The principal amounts, maturities, coupon, and yields for these bonds are displayed in Table 11. The difference between the coupon and the yield is a function of the actual price paid for the bond. If the bond sells at face value, then the coupon is the same as the yield. If the price paid for the bond is higher than the face value, then the yield will be lower and vice versa. The semiannual maturity shown in the table is unusual. Also, the table includes a mix of callable and non-callable bonds, which account for the differences in yield.

Banks also rely on repayment sculpting to support project ramp-up phases and revenue projections. They may offer a period of interest-only payments during construction and after (referred to as "grace period") to provide some relief to the project. They may also offer different repayment scenarios, such as fixed principal payment or fixed total payment based on the project cash flows.

While P3s sourcing debt from the public capital markets typically issue long-term bonds at the outset, P3s alternatively may rely on construction loans and subordinate loans to satisfy financing needs during construction and other periods in the contract term. Construction loans usually are replaced with long-term financing once the project is operational, or they may be paid off with milestone payments from the public authority. Some public authorities see value in construction lenders and the discipline they may bring to construction monitoring and cash flow management. This is one rationale for providing milestone payments at different stages of construction. Another motivation is reducing long-term interest expense by insulating permanent lenders from construction completion risk. Cash flow management on the public side is another rationale. This is the motivation behind Florida's extensive design-build-finance (DBF) program, where short-term financing is used to accelerate projects in advance of future years' internally available resources, federal aid, and bond proceeds. Projects may also rely on bond anticipation notes (BAN) and construction loans to be paid off with TIFIA loan proceeds as long as all of the short-term loan proceeds are used for TIFIA-eligible project costs.

| CUSIP | Maturity | Principal, US$ | Coupon, percent | Yield*, percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 928104KW7 | 1/1/2022 | 670,000 | 4.25 | 4.45 |

| 928104KX5 | 1/1/2023 | 685,000 | 4.50 | 4.60 |

| 928104KY3 | 7/1/2023 | 1,775,000 | 5.00 | 4.60 |

| 928104KZ0 | 1/1/2024 | 1,760,000 | 5.00 | 4.75 |

| 928104LA4 | 7/1/2024 | 2,900,000 | 5.00 | 4.75 |

| 928104LB2K | 1/1/2025 | 3,080,000 | 4.75 | 4.90 |

| 928104LC0 | 7/1/2025 | 4,875,000 | 5.00 | 4.90 |

| 928104LD8 | 1/1/2026 | 5,290,000 | 5.00 | 4.95 |

| 928104LE6 | 7/1/2026 | 6,700,000 | 5.00 | 4.95 |

| 928104LF3 | 1/1/2027 | 6,150,000 | 5.00 | 5.00 |

| 928104LG1 | 7/1/2027 | 8,480,000 | 5.00 | 5.00 |

| 928104LH9 | 1/1/2032 | 91,795,000 | 5.25 | 5.25 |

| 928104LJ5 | 1/1/2037 | 209,185,000 | 6.00 | 5.32 |

| 928104LK2 | 1/1/2042 | 320,405,000 | 5.50 | 5.50 |

| Source: Midtown Tunnel Official Statement available

from MSRB EMMA database, CUSIP 928104LK2. *The rate is the rate offered to bond buyers. When bonds are sold, they often do not sell at face value but at either a premium or a discount. The yield indicates the actual return offered to bondholders based on the actual price paid. |

||||

Other public authorities have adopted a different approach by providing upfront public subsidies instead of milestone payments. Under this scenario, private partners are still obliged to adhere to the construction schedule, but they invoice against committed state funds as well as bond proceeds and, if needed, their own equity during construction.

While individual bonds do feature balloon payments, in that they feature interest-only payments until their maturity when full principal is due, bond financing of large-scale transportation projects in the US, including P3s, involves the issuance of a whole series of bonds for individual projects. As discussed previously, the maturity of these bonds is typically spread out over a range of years. In the case of Midtown Tunnel, bonds mature over a period of 10 to 30 years. On the other hand, East End Crossing's Series B PABs in the amount of $195 million are essentially construction financing coming due in 2019 and priced to yield 2.28 percent.

Bank financing will include amortization beginning at least in the second year of the loan. Prior to the financial crisis, it was possible to obtain interest-only loans with balloon payments, and these may return to the market at some point. Principal payments may be constant or increasing to match decreasing interest payment on a total fixed payment arrangement. On availability payment deals, banks may be able to offer loans of up to 20 years, but on revenue risk deals, they are unlikely to offer loans longer than 7 years. If project cash flows are not sufficient to repay a loan in 7 years, then the project may face refinancing risk. Even before the crisis, many P3s internationally relied on 10-year bank loans with the government accepting refinancing risk. This is typically not an issue in the US, where bank loans have been used almost exclusively for short-term construction financing with bond financing offering terms up to 40 years, thereby eliminating refinancing risk.

A cash sweep, or debt sweep, is the mandatory use of excess free cash flows to pay down outstanding debt rather than distribute it to shareholders. Debt providers consider how far the ability to slow down distributions to shareholders mitigates their risk. They model the impact in a number of stress tests or downside scenarios. Alternatively, part of the sweep proceeds can be placed in a debt service reserve account. A cash sweep may be used where a balloon payment structure exists, to encourage refinancing of the debt well before the final balloon repayment date. It may also be used where there is uncertainty about the growth of future revenues, where lenders are concerned about the tail risk, or where substantial costs are to be incurred a long time into the future, such as for renewal, replacement, or expansion of the highway facility.

Credit enhancement involves the use of both internal structural provisions and external financial guarantees from higher-rated entities to provide greater security to creditors, thereby lowering default risk and reducing financing costs. Some of these techniques can result in a higher credit rating on the debt obligations than would be attainable otherwise. Various forms of credit enhancement and their purpose are listed in Table 12. They are described further in the sub-sections that follow.

| Type of Enhancement | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Internal Credit Enhancement | |

| Cash Reserves | Cover debt service or other expenses if net revenues are insufficient |

| Debt Tranching | Obtain higher rating on most of debt by making a portion of it junior lien |

| Cash Flow Optimization | Enhance debt through applying excess cash to prepaying portions of it ahead of scheduled amortization. |

| External Credit Enhancement | |

| Letters of Credit | Guarantee debt service to investors |

| Lines of Credit | Working capital for project sponsor |

| Bond Insurance | Guarantee debt service to investors |

| Governmental Guarantees | Guarantee debt service to investors or subsidize operations |

| Construction Risk Guarantees | Protect against contractor default |

The establishment of cash reserves provides resources to meet obligations in the event that pledged project revenues prove insufficient to meet semiannual principal and interest payments or other project spending requirements. Reserves usually are managed by a trustee acting on behalf of bondholders who has specific instructions that indicate under what conditions reserves are to be paid out, either to bondholders or to the borrower, depending upon the nature of the reserve. Under traditional P3 models, reserves are built up after project completion from the project's initial earned revenues. When bond financing is used, it is typical to establish certain reserves (such as the debt service reserve fund) upfront with bond proceeds. Reserves may drive up project costs and financing requirements but also provide additional security for investors.

Typical reserve accounts used in connection with project financing are:

A project can also structurally enhance the creditworthiness of a portion its debt financing by segmenting it into a senior tranche ("slice" of indebtedness) and a junior or subordinate tranche. Giving certain bondholders or creditors a first claim on revenues before other bondholders provides a higher level of debt service coverage for the senior holders, and often can result in a higher rating for that portion compared to all the debt being uniformly secured. Because there is lower risk on the higher rated debt, the more attractive interest cost achieved on the senior portion can more than offset the interest cost of selling the smaller tranche of lower-rated subordinate debt.

Project sponsors may enhance the creditworthiness of debt obligations through other structuring techniques as well. For example, structuring the annual "flow of funds" so that all or a set percentage of residual cash flow are captured through a "cash sweep," and using it to accelerate (prepay) portions of the outstanding debt, reduces bondholder exposure in the out years. Equity lockups and similar mechanisms provide additional security for lenders by limiting conditions under which cash flow may be released to equity holders, decreasing the risk of default on the debt. In addition, setting the term of a P3 agreement so that it extends well beyond the final maturity date of the debt obligations issued to finance a project provides latitude for restructuring and extending the debt to be repaid over a longer time period. All of these mechanisms add security to bondholders and lenders.

A Letter of credit (LOC) is a form of guarantee typically provided by a commercial bank that assures the recipient of full and timely payments. In the context of project finance, an LOC would take the form of a bank guaranteeing to a creditor (lender or bondholder) that debt service payments would be received as they became due. If the LOC is from a highly-rated bank and covers the full amount of principal outstanding plus accrued interest due on the payment date, the bond rating will reflect the bank's rating rather than the (lower) underlying rating of the project. Although LOC's are used to secure long-term (25 to 30 year) bond issues, the bank commitment typically extends only 5-10 years. If the bank elects not to renew its LOC at the end of the commitment term, either a substitute bank must be brought in with at least as high a credit rating, or the bonds must be redeemed with a final draw on the LOC and the issuer is forced to refinance the issue.

LOCs often are used in connection with variable rate demand obligations (VRDOs), which are floating rate securities that allow the bondholder to put or tender the bond back on a weekly or monthly basis. VRDOs were quite prevalent 10-15 years ago, but as a result of sustained low long-term interest rates and the decline in the credit ratings of many of the major banks, LOCs are much less common today. For example, the Bond Buyer Annual Review, an industry trade publication, reports that the volume of new municipal bond issues backed by letters of credit declined from $71.5 billion in 2008 to just $3.3 billion in 2014 - a 95% reduction. The obligor pays annual commitment fees to the bank providing the letter of credit, and to the extent the LOC is drawn upon, such advances must be repaid to the bank with interest over a defined "reimbursement period" (e.g., five years). The borrower will determine the cost-effectiveness of the bank's credit enhancement by comparing the rate on the LOC-backed issue plus annual bank fees to its own cost of borrowing without enhancement.

A Line of credit differs from a letter of credit, in that it is a standby lending commitment from a bank generally issued in favor of the obligor, not the creditor, within specified limits. Lines of credit offer liquidity on demand for project companies. They can be used for general working capital needs of the project, typically arranged at project start-up or once project revenues have begun. They offer coverage in the case of a cash flow shortfall and may be used by the borrower for debt service or for operational expenses. But they do not directly provide the bondholder with a guarantee protecting them from default risk. Lines of credit also may be used to repurchase bonds with a "put" feature that have been tendered back to the project company issuer but have not yet been remarketed to new investors.

The obligor pays annual commitment fees to the bank providing the line of credit, and any draws on the bank facility must be repaid typically within five years at interest set at some margin over the prevailing short-term London Interbank Overnight Rate (LIBOR), an international benchmark lending rate.

Monoline bond insurers use their capital base and high ratings (AAA in the best scenario) to support project financings by guaranteeing repayment, thus sharing some of the risk and reducing the price (interest rate) charged by debt providers for financing. The borrower typically pays the insurer a guarantee fee (the bond insurance premium) upfront out of bond proceeds. If the borrower defaults, the insurer steps in and pays principal and interest as originally scheduled. As with the bank LOC's, issuers take into account the cost of the credit enhancement (the bond insurance premium) in determining whether the guarantee is cost-effective.

Prior to the 2008 financial crisis, seven monoline insurers carried AAA ratings, and bond insurance was widespread - over 57% of all new municipal bond issues were insured in 2005. However, many of these insurers guaranteed subprime mortgage financings and were downgraded as a result of their exposure to those assets and/or because of indirect effects of the subprime crisis. In 2014, only 5.5% of new issues were insured. However, several new monoline insurers are back in the market with AA ratings (Assured Guaranty and Build America Mutual), and there have been some recent P3 financings with monoline support internationally. They may once again become a widespread source of financial guarantees in the US P3 market.

A governmental project sponsor can provide credit enhancement to local projects through various mechanisms, ranging from contingent funding commitments to outright guarantees. For example, the City and County of Denver provided a long-term "moral obligation" commitment to support up to 50% of the debt service payable on a Federal Railroad Administration loan secured by projected tax revenues in a tax increment district surrounding the newly expanded Denver Union Station. For the Number 7 subway line extension in Manhattan and related pubic improvements, the City of New York agreed to pay interest on $3 billion of tax increment bonds issued by the Hudson Yards Infrastructure Corporation, reducing the level of project revenues needed to cover debt service and thereby helping it obtain an A2 bond rating.

Governmental project sponsors may also provide credit enhancement indirectly, by assuming certain project operating costs, thereby allowing all project revenues to first be applied to debt service. For example, for the $1.0 billion Triangle Expressway, a 20-mile toll road near Raleigh, NC, debt service payments rank higher in priority claim on annual toll revenues than do annual operations and maintenance expenses. This is possible because NCDOT has agreed to pay O&M costs from the State Highway Trust Fund should toll revenues be insufficient after meeting annual debt service requirements. By inverting the typical flow of funds sequencing, where the first revenues received normally would pay for operations, NCDOT has enhanced the credit profile of this project, enabling it to obtain an investment grade rating of Baa3.

State/local sponsors can also "over collateralize" a new project financing by making available additional revenue streams to augment project-generated revenues. For Virginia Department of Transportation's Downtown/Midtown Tunnel project (described elsewhere in this Guidebook), new toll revenues on an existing tunnel are supplementing tolls to be collected on the new harbor crossing to help finance this $2.1 billion project.

At the federal level, the loan guarantees that are technically available (but virtually unutilized) under the TIFIA and RRIF credit programs represent a potential source of credit enhancement. Such guarantees would command a AAA rating, based on the irrevocable promise of the United States to pay principal and interest on the guaranteed obligations. However, project sponsors have instead preferred to obtain federal credit assistance in the form of direct loans, because of the lower interest rates and more flexible structuring and repayment terms.

Various external credit enhancement mechanisms are used to reduce the risk of project construction not being completed because of contractor performance issues.

Private sector companies usually participate in P3 projects through subsidiaries or special purpose vehicles (SPVs). The objective is not solely to limit the parent company's financial exposure. Indeed, a separate governance structure around a project is necessary to provide delegated authority and the autonomy needed to motivate project executives. The rationale for the SPV structure is discussed in detail in chapter 2.

The public authority project sponsor, however, reasonably requires parent company financial engagement over and above the reputational risk for the private companies undertaking construction of the project. As described below under "Contractor Surety Bonds," construction contracts typically require various surety policies, and may additionally require bank letters of credit covering a limited percentage of the value of the contract. Debt providers consider the amount of such financial guarantees in stress testing the project for downside scenarios. If the amount of parent equity investment in the SPV and/or the surety policy backstopping of the SPV's contractual obligations proves insufficient in some scenarios, debt providers may ask for the parent companies to guarantee the provision of greater amounts.

In the US, parent companies typically guarantee compliance with all financial and technical requirements of the design-build agreements that form part of the overall P3 agreement. They also guarantee equity contributions to project financing by the project company, which commitment may be further backed by a bank letter of credit. Parent companies have also pledged contingent capital to supplement any shortfalls in toll revenues during construction (in the case of Midtown Tunnel) and to replenish reserve accounts (in the case of LBJ-635).

A contractor surety bond is a guarantee, in which the surety guarantees that the contractor, called the "principal" in the bond, will perform its obligation to construct the project, as stated in the bond. It normally remains in full force and effect until the contractor fully performs the stated obligation. For example:

If the principal fails to perform the obligation stated in the bond, both the principal and the surety are liable on the bond, and their liability is "joint and several." That is, the principal, the surety, or both may be sued on the bond, and the entire liability may be collected from either the principal or the surety. The upward limit on the amount that may be collected is the amount in which a bond is issued (known as the "penal sum," or the "penalty amount," of the bond).

The beneficiaries (or obligees) of the bond depend on the applicable State and Federal statutes that require surety bonds on public projects. On bid bonds, performance bonds, and payment bonds, the obligee is usually the owner. In the case of a P3 project, this may be the project company. Where a subcontractor furnishes a bond, however, the obligee may be the project company, the general contractor, or both. In such cases, an owner must require a "dual oblige" rider.

The Miller Act of 1935 requires performance bonds for Federal construction projects, and subsequent "Little Miller Acts" at the State level require bonding for State projects. 19 While states may require performance bonds for 100 percent of the contract value for smaller projects, large mega-projects typically have only a limited portion of the total contract value covered by a performance bond, due to market capacity limitations. Performance bonds typically add 1.5 percent to project costs. 20 For comparison, Canada requires bonding at 50 percent, and the UK requires bonding at 10 percent. The rationale for different levels of bonding differs from country to country. Where the bonding requirement is low, the aim is for the public authority to have sufficient funds to re-tender the project to select another contractor. In the US, the rationale is for the public authority to have sufficient funds for the project to be completed.

Surety requirements have not been adjusted in light of P3 project structures, under which equity investors also cover some risks. There are some efforts underway to reduce the bonding requirements. 21

Surety providers may not pay immediately. They may try to negotiate a settlement or litigate. This is why debt providers prefer letters of credit. However, surety providers can and do pay out and even take control of the project to ensure completion. In fact, sureties were responsible for managing the completion of the Big Dig project in Boston after the default of Modern Continental. 22

Surety providers have responded to market concern over probability of payouts with a product referred to as a demand-pay surety, or surety with a liquidity layer. This product features a portion of the available payout that is made immediately to support continued progress on the project while the surety investigates the cause of the cash flow short fall and who is to blame.

P3 financing is a complex process with a number of moving parts. Public authorities generally seek expert advice, not only from financial advisors but also from other public authorities and Federal, state, and local agencies that have undertaken similar projects. While rating agencies do not directly advise issuers on how to structure their transactions, they do publish reports describing the criteria they use in determining bond ratings, and their credit reports on specific offerings are important sources of information for bond issuers, underwriters and advisors as well as investors,

One goal of a public authority is to minimize costs. However, this is not the only goal. Even within the public finance market in the US, the use of revenue bonds as the predominant financing tool recognizes the benefits of project finance approaches that may be more expensive than general obligation financing but offer other benefits, including off-balance sheet borrowing and project finance ring-fencing.

Public authorities may seek to maximize the level of equity in a project to ensure that the private developer has "skin in the game." However, equity is more expensive than debt, so raising the level of equity also raises project costs, whether those are paid by users in the form of tolls or by the public authority in the form of availability payments.

Credit enhancements - including cash reserves, lines of credit, surety, and insurance - help to ensure project financial sustainability, but they also carry a cost. The cost of each of these instruments needs to be weighed against the benefits and viewed in light of project-specific features.

The US P3 market is experiencing a renaissance. Many P3 models have been imported from international markets. For example, it is common in other countries for the public authority to accept demand risk (and in this way provide a type of project subsidy) by structuring availability payment projects. The public authority then requires the private partners to raise their own financing from private sources. In the US, across many sectors, it is more common to require the private partner to take on demand risk but to then subsidize its financing in the form of tax-exempt debt and government loan programs.

Since debt is typically less expensive than equity, the high leverage that is typical in project finance is one way to minimize costs. For example, if a project is expected to yield $100 million in net toll revenue in its first year with an increase in revenue of $1 million per year over 33 years, then CFADS is $100 million in the first year, increasing to $133 million in year 33. Given a 2.0 required coverage ratio, the maximum debt service for the project is $50 million in year 1 and $67 million in year 33. Over a 33-year term, total maximum debt service is equal to $1.739 billion (see Table 13).

The amount of financing that can be raised from this revenue stream depends on the structure of repayment. P3 projects typically have complex financing structures, potentially involving a large number of debt and equity instruments. The financing/funding structure would typically include equity, debt and public Agency subsidy payments. Debt service can be structured in two ways:

The total debt size under annuity-type debt service is determined by the minimum Debt Service Coverage Ratio (DSCR, an input) and the minimum cash flows available for debt service (CFADS), which typically occur in the early years. An example of an annuity-type debt service is shown in Figure 13 below.

Figure 13. Annuity-type Debt Service

View larger version of Figure 13

Under a fully sculpted debt service (see Figure 14 below), the project's cash flows available for debt service (CFADS) in each year are used to create a perfectly sculpted repayment profile. This means that the DSCR will be constant throughout the debt service period. Under this approach, the total debt size is determined by the minimum DSCR and the CFADS over the entire debt service period. This may also lead to some interest capitalization during the early years of operation if CFADS in these early years is insufficient to make early interest payments. Although the CFADS under both debt service types are equal, a fully sculpted repayment makes more efficient use of these CFADS by "pushing back" debt service to future periods with higher revenues. As a result, the debt capacity of a fully sculpted debt solution will be larger than the debt capacity of an annuity-type debt solution.

Figure 14. Fully Sculpted Debt Service

View larger version of Figure 14

In reality, P3 transactions will typically try to create a more or less sculpted debt profile using various debt instruments.

For our $100 million net revenue example, let us assume a 5.0 percent interest rate for two options:

These options are displayed in Table 13 and Figure 15. If we assume Option 2, with a bond repayment structure the total amount of funds raised (principal) will be $769 million. If we assume Option 1 with fully sculpted debt service for the 33-year term, we can raise $860 million.

| Revenue | Sculpted Debt Service | Level Debt Service | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interest rate: | 5.00% | Interest rate: | 5.00% | |||||

| Tenor: | 30 | Tenor: | 30 | |||||

| Total Principal: | 860 | Total Principal: | 769 | |||||

| Total Interest: | 879 | Total Interest: | 731 | |||||

| Total Debt Service: | 1,739 | Total Debt Service: | 1,500 | |||||

| Principal Payments | Interest Payments | Total Debt Service | Outstanding Principal | Principal Payments | Interest Payments | Total Debt Service | Outstanding Principal | |

| 100 | 7 | 43 | 50 | 853 | 12 | 38 | 50 | 757 |

| 101 | 8 | 43 | 51 | 845 | 12 | 38 | 50 | 745 |

| 102 | 9 | 42 | 51 | 837 | 13 | 37 | 50 | 732 |

| 103 | 10 | 42 | 52 | 827 | 13 | 37 | 50 | 719 |

| 104 | 11 | 41 | 52 | 816 | 14 | 36 | 50 | 705 |

| 105 | 12 | 41 | 53 | 804 | 15 | 35 | 50 | 690 |

| 106 | 13 | 40 | 53 | 792 | 16 | 34 | 50 | 674 |

| 107 | 14 | 40 | 54 | 778 | 16 | 34 | 50 | 658 |

| 108 | 15 | 39 | 54 | 762 | 17 | 33 | 50 | 641 |

| 109 | 17 | 38 | 55 | 746 | 18 | 32 | 50 | 62311 |

| 110 | 18 | 37 | 55 | 728 | 19 | 31 | 50 | 604 |

| 112 | 19 | 36 | 56 | 708 | 20 | 30 | 50 | 584 |

| 113 | 21 | 35 | 56 | 688 | 21 | 29 | 50 | 564 |

| 114 | 23 | 34 | 57 | 665 | 22 | 28 | 50 | 542 |

| 115 | 24 | 33 | 57 | 641 | 23 | 27 | 50 | 519 |

| 116 | 26 | 32 | 58 | 615 | 24 | 26 | 50 | 495 |

| 117 | 28 | 31 | 59 | 587 | 25 | 25 | 50 | 470 |

| 118 | 30 | 29 | 59 | 557 | 27 | 23 | 50 | 443 |

| 120 | 32 | 28 | 60 | 525 | 28 | 22 | 50 | 415 |

| 121 | 34 | 26 | 60 | 491 | 29 | 21 | 50 | 386 |

| 122 | 36 | 25 | 61 | 454 | 31 | 19 | 50 | 355 |

| 123 | 39 | 23 | 62 | 416 | 32 | 18 | 50 | 323 |

| 124 | 41 | 21 | 62 | 374 | 34 | 16 | 50 | 289 |

| 126 | 44 | 19 | 63 | 330 | 36 | 14 | 50 | 254 |

| 127 | 47 | 16 | 63 | 283 | 37 | 13 | 50 | 216 |

| 128 | 50 | 14 | 64 | 233 | 39 | 11 | 50 | 177 |

| 130 | 53 | 12 | 65 | 180 | 41 | 9 | 50 | 136 |

| 131 | 56 | 9 | 65 | 123 | 43 | 7 | 50 | 93 |

| 132 | 60 | 6 | 66 | 64 | 45 | 5 | 50 | 48 |

| 133 | 64 | 3 | 67 | 0 | 48 | 2 | 50 | 0 |

| 3,478 | 860 | 879 | 1,739 | 769 | 731 | 1,500 | ||

Figure 15. Plots showing Two Types of Repayment Structures

View larger version of Figure 15a

(a) Sculpted Debt Service

View larger version of Figure 15b

(b) Level Debt Service

Beyond these two simple examples, there are many variations and combinations that can be used to optimize debt financing. Banks may be flexible with coverage ratios and principal payments at the beginning of the project. Banks typically offer monthly draw schedules that allow the project company to borrow funds on an as-needed basis. Bond financing, on the other hand, typically features the raising of the total sum of principal in a single financing. This means that some of the funds are idle during the construction period. They are typically reinvested into short-term, low-risk securities such as Treasury obligations that offer an interest rate lower than the interest rate paid on the bond, producing "negative carry." The level payment structure of a bank loan may be more suitable for an availability payment deal, whereas the interest-only structure of bond financing may be preferred for a greenfield toll road that includes a ramp-up period. However, but investors in project financings will want to see an amortization schedule for the principal borrowed, based on forecasted free cash flow. In the US most availability payment deals have featured large milestone payments that have reduced the need for long-term financing.