List of Figures

States are exploring value capture techniques for several reasons. First, they raise needed revenue. Second, if properly designed and implemented, they can help integrate infrastructure investments with land use objectives by encouraging development near existing infrastructure, thereby reducing the sprawl that harms the environment and burdens taxpayers. Third, value capture techniques can enhance equity by operating more like fees than taxes. In other words, they raise revenues from those who benefit from infrastructure in proportion to the benefits received or from those who demand its expansion in proportion to the costs imposed. Fourth, if support for a tax increase is weak, value capture can be another revenue opportunity to fund infrastructure needs.

Simply put, "value capture" is "value returned because value was received. By this definition, value capture encompasses user fees, access fees, and mitigation fees or requirements. User fees, such as the per gallon fee for water, highway tolls, transit fares, parking meter fees, etc., are rarely mentioned in the "value capture" discussion. Access fees, such as special assessments, seek to recoup publicly created land values from property owners who would otherwise receive a windfall profit at other taxpayers' expense. Access fees can also be referred to as "land value return."[1] Mitigation fees or requirements, such as exactions and impact fees, seek reimbursement from private development activity when it would otherwise impose costs on other taxpayers who neither caused nor benefited from those expenditures.

As States explore value capture implementation, they seek to understand the legal prerequisites and standards applied to these techniques. This report explores some of these legal issues.

States hold broad powers to impose taxes and fees, subject primarily to due process and uniformity requirements in federal and state constitutions and statutes. To the extent that a State delegates these powers, local jurisdictions may also impose taxes and fees pursuant to the delegation and according to the same due process and uniformity requirements. Thus, value capture techniques must meet uniformity and due process requirements.

Additionally, under some circumstances, some value capture techniques could be challenged pursuant to the "takings" clause of the Fifth Amendment. The reason for this is that, unlike a tax applied to all persons and property in a jurisdiction equally, many value capture techniques apply to some properties but not to others. If properly implemented and administered, these differences are justified and do not violate the Fifth Amendment.

In the case of infrastructure access fees (such as special assessments), some properties are receiving special benefits that are not available to other persons or property generally. Therefore, it is fair (and legal) for a community to charge beneficiaries for such special benefits. In the case of mitigation fees, private development is imposing a cost on the general public by requiring new infrastructure or capacity expansion for existing infrastructure. To the extent that a private development project will impose costs on the community, it is fair (and legal) for a community to seek reimbursement for these costs (or to avoid them) by requiring compensation (or in-kind infrastructure provision) from the development projects.

"If properly implemented and administered" is an important phrase. Private property owners are reluctant to part with funds or to incur publicly mandated costs. Their self-interest encourages them to see value capture techniques as arbitrary, non-uniform or as uncompensated "takings."

Receiving a windfall benefit from a public infrastructure project or imposing infrastructure creation or expansion requirements on a community are closely related to each other despite representing impacts to opposite parties.[2] In one instance, a private party is receiving a benefit without providing compensation. In the other, a private party is imposing costs upon others without providing reimbursement.

Nonetheless, when a community seeks reimbursement from a private party for imposing a cost on that community (through the imposition of exactions or impact fees), a community justifies this reimbursement by showing:

Similarly, when a community infrastructure project provides a special benefit to private property, the community might obtain compensation from that private property by imposing a special assessment. A community justifies this assessment by establishing:

Although the Supreme Court developed the "essential nexus" and "rough proportionality" tests in the context of exactions and impact fees, because special assessments are related (albeit by addressing benefits bestowed rather than mitigating costs imposed), jurisdictions and courts apply the same standards there as well.

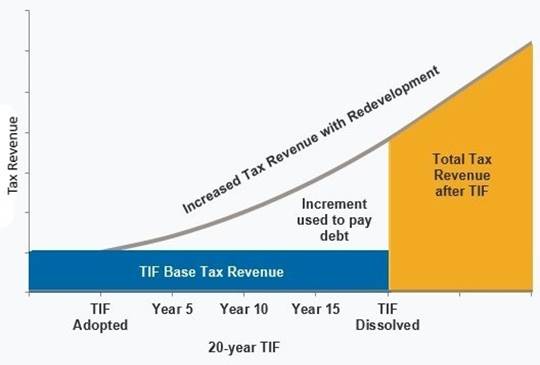

Source: Kentucky League of Cities, https://www.klc.org/infocentral/detail/26

The key to this graphic is that revenues increase after TIF creation NOT because of higher tax rates, but because of increased development and economic activity that are subject to the existing tax rates. Although there have been academic critiques of the validity of the but-for assumptions, there has been little litigation of this requirement. In the illustration, benchmarked public revenues would remain constant if the public infrastructure project is not completed.

This might be true under certain circumstances, but under other circumstances, benchmarked revenues might decline in the absence of the project or they might increase—but by a smaller amount than if the project were undertaken. The definition of the tax increment can be and should be refined to reflect the actual situation in a particular place at a particular time. The critiques of TIF referenced later in this report provide analytical methodologies for determining the extent to which the but-for test could be satisfied. The judicial decisions on this topic summarized later in this report how that courts are reluctant to second-guess the findings of a legislative body.

THF based on the following assumptions:

This report concludes by exploring some analytical methods and tools for determining the extent of benefits received (or costs imposed) by properties in order to equitably apportion infrastructure costs among those who benefit from (or impose costs upon) infrastructure systems. Jurisdictions that follow the substantive and procedural requirements contained in value capture enabling statutes and that carefully analyze the special benefits created by public infrastructure (or the costs imposed by private development) will implement value capture techniques in a manner that is likely to survive legal challenges based on due process, uniformity, essential nexus and rough proportionality. Following these requirements should also meet the but-for test applied to TIFs.

[1] NCHRP Report 873, "Guidebook to Funding Transportation Through Land Value Return & Recycling," (2018)

[2] Abraham Bell and Gideon Parchomovsky, Givings, 111 Yale Law Journal 547 (2001). https://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4571&context=ylj . See also Rick Rybeck, ""Avoiding Mis-Givings: Recycling Community-Created Land Values for Affordability, Sustainability and Equity," Journal of Affordable Housing and Community Development Law, Vol 28 No 2, October, 2019, pp 299-323. https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/publications/journal_of_affordable_housing/Volume28_Number2/ah_journal_10_18_19.pdf