List of Figures

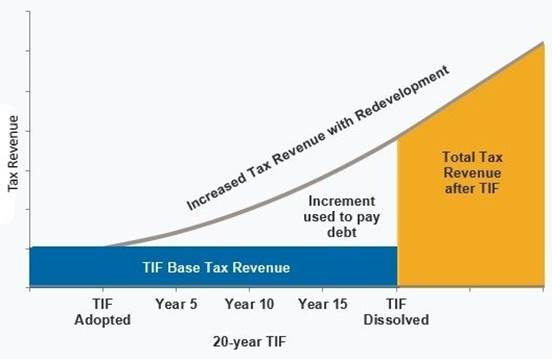

Another approach to value capture involves tax increment financing (TIF). In economically distressed areas, infrastructure improvements might be necessary to induce development. Yet, because of economic distress and a lack of economic activity, revenues may not be available for making such improvements. TIF was created for such situations. The concept is simple:

Source: Kentucky League of Cities website at https://www.klc.org/InfoCentral/Detail/26

Revenues increase after TIF creation NOT because of higher tax rates, but because of increased development and economic activity that are subject to the existing tax rates. In this illustration, benchmarked public revenues would have remained constant if the public infrastructure project had not been undertaken. This might be true under certain circumstances, but under other circumstances, benchmarked revenues might decline in the absence of the project or they might increase—but by a smaller amount than if the project were undertaken. The definition of the tax increment can and should be refined to reflect the actual circumstances in a particular place at a particular time.

TIF supporters claim that infrastructure improvements are being paid for by revenue from economic development that would not occur without these improvements. Therefore, these infrastructure improvements appear to be self-financing. In other words, TIF is an example of value capture whereby a portion of private economic gain, created by public infrastructure investment is returned to the public sector to pay for that public infrastructure.

This relatively simple funding/financing technique rests on three primary assumptions:

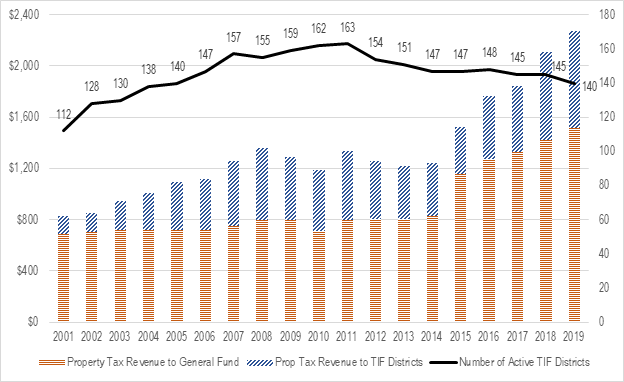

Based on these assumptions, TIF-funded infrastructure projects can be funded without reducing spending on existing programs or projects and without increasing tax rates. Taxpayers are subject to the same tax rates regardless of whether a TIF is implemented or not. It is only the increase (increment) in revenue, derived from increased economic activity, that funds the TIF portion of an infrastructure project. The ability to fund infrastructure projects without competitive spending or tax rate increases is politically advantageous. As a result, this technique has become very popular.[56] The popularity of TIFs can be seen in Figure 3, which shows the growth in the number of TIF districts and TIF revenue in Chicago from 2001 until 2019.[57] The figure shows the changing number of TIF districts in Chicago while also showing total property tax revenue allocated to the general fund and total property tax revenue dedicated to TIF districts.

Source: Sean McCarthy, Tax Increment Financing in Arizona, ATRA, 2017, p. 2. http://www.arizonatax.org/sites/default/files/publications/special_reports/file/tif_in_arizona.pdf

The widespread use of TIFs has generated concerns that TIF revenues might be reducing general fund revenues and thereby depriving public services of funding. This concern has focused attention on TIFs' underlying assumptions.

Assumption number one is that tax revenues in the affected area will not increase but-for the improvement of specified infrastructure which will catalyze private sector development and other economic activity. If this assumption is not true, and tax revenues would have increased anyway, then a TIF deprives the general fund of revenues and diminishes resources for existing projects and programs.[58] For this reason, some state enabling statutes limit TIFs to blighted areas where development is not otherwise occurring.[59]

Although some parcels reside in a single taxing jurisdiction, other parcels might exist in multiple taxing jurisdictions. For example, a property might receive a single property tax bill including taxes to be paid to a city, a county, a State, a school district, a water and sewer district, and a road improvement and maintenance district. Typically, only one of these tax authorities is authorized to implement a TIF, but implementing a TIF could potentially affect revenues for these other taxing authorities. Where multiple taxing authorities exist, the process for creating a TIF might be more complex and controversial. This complexity is not insurmountable. It does, however, require more outreach, negotiation and possibly inter-jurisdictional agreements to protect each jurisdiction's interests.

Assumption number two is that increases in development and economic activity will yield sufficient additional tax revenues to fund the specified infrastructure improvements. If this assumption is false, then either additional funding sources will be required to repay the debt or infrastructure project lenders won't be repaid. If additional funding sources are required, then in all probability the infrastructure project will compete for funding with other projects and programs.

Assumption number three is that new growth induced by the TIF will not generate new demands for increased government-funded facilities or services other than the TIF-funded project. Some types of development catalyzed by a TIF may not place additional demands on government-funded infrastructure and services like schools, parks, traffic management, police, fire and EMS services, hospitals, water supply, waste treatment, etc. However, if a TIF generates an increased demand for these public facilities or services, TIF-designated revenue sources will not cover their costs.[60] Consequently, supplemental funding for the general fund or general fund access to a portion of the tax increment may be justified and equitable. Some jurisdictions have modified their TIF enabling legislation to accommodate such arrangements.[61]

Assumption number four is that increases in development and economic activity in a TIF district are not displacing or inhibiting growth in another location. If this assumption is false, then revenue might increase in a TIF district but might not grow as fast or might actually decline in another location as a result of the TIF-induced growth.[62] Consequently, overall net revenues might not grow as much as they might appear to be based only on a review of revenue in the TIF district. This is particularly relevant if different governmental jurisdictions are involved and competing for growth and development using TIF as a growth inducement.

Shifting development from one location to another location might be valuable and satisfy a legitimate public purpose. But it won't satisfy the assumption that the tax increment would not exist but for the TIF project.

Most States authorize TIF.[63] The only exceptions appear to be Arizona and Puerto Rico. However, each State's TIF legislation is unique. Some TIF-authorizing statutes might limit the creation of TIFs to projects that are necessary to catalyze increases in economic activities and resulting tax revenue. This is known as the but-for test:

Imagine that a jurisdiction's legislature is considering spending taxpayer dollars on an infrastructure project that will confer a significant benefit on a few property owners or businesses. In all probability, such a proposed project, funded out of the jurisdiction's general fund revenues, would be opposed because public tax dollars should not be spent to benefit private entities. TIF solves the problem of using public funds for private gain by claiming that, but for the infrastructure project, these public tax revenues would not exist. In other words, economic activity generated by the project, that would not otherwise exist, will produce the revenue used to fund or finance the project. This but-for claim suggests that the project is paying for itself, and not transferring wealth from the public sector to the private sector.[64]

Does the but-for test create equity by ensuring that new development pays for itself? Typically, taxpayers in a TIF district pay taxes at the same rate as they would if the TIF district did not exist. When new development occurs, it often requires additional public goods and services. The taxes paid by new developments (the tax increment) typically cover a portion of the new operating expenses associated with these additional public goods and services. But, when a TIF district is created, the tax increment is dedicated to fund a particular infrastructure project and is therefore unavailable to cover increased costs for providing other public goods and services to new developments in the district for the duration of the TIF, which can be a substantial number of years.[65] This can create hardships for other agencies affected by TIF induced growth.

In 1972, concerns that California TIFs were depriving schools of property tax revenue were addressed when the State promised to reimburse school districts for lost TIF revenues.[66] More recently, in 2016, Chicago created a TIF for transit. This TIF was structured so that Chicago Public Schools would receive their proportionate share of TIF revenues (based on their share of regular property tax revenue). Of the remainder, 80 percent would go to the Transit TIF and 20 percent to other taxing districts.[67] And, in some States, the State TIF-enabling statute mandates approval from other tax districts when an overlapping taxing authority creates a TIF potentially impacting their revenue.[68] These types of modifications to the TIF structure could provide for greater equity and political support.

The preceding paragraphs raise a concern that new developments in a TIF district might not pay their fair share of government operating expenses. And, if new developments create a need for new infrastructure capacity, then the new developments would not be paying for this capital expense either.[69] Thus, the mere fact that a development generates tax revenue that would not otherwise exist (thereby satisfying the but-for test) does not mean that a TIF will not have an adverse impact on a jurisdiction's existing public goods and services.

A Public Policy Institute of California study compared 38 California TIF districts to similar areas without TIFs. Because baseline tax assessments increased in the non-TIF areas during the same time period, only four TIF districts were found to generate enough new revenue to be self-financing.[70] This implies a need for equity adjustments. Therefore, to avoid or minimize diverting funds from existing public goods and services, some TIF laws require a finding that increased tax revenues within a TIF district (the tax increment) would not exist but for (in the absence of) the infrastructure project being funded by the tax increment revenues.

Even if infrastructure investment increases land values, property owners are paying taxes at the same rate they would otherwise pay in the absence of a TIF. Thus, "value capture" is limited to what these taxes would accomplish even in the absence of a TIF. Although property tax rates vary from place to place, the national average is about one to two percent of value paid annually.[71] A present value calculation shows that such a tax on a long-lived asset (like land) in an economic environment where interest rates are five percent returns between 20 percent and 40 percent of the publicly created land value.[72]

Thus, to the extent that infrastructure investments lead to higher land values, the lion's share (60 percent to 80 percent) end up as windfall gains to affected landowners. Given concerns over growing inequality, spending public funds to benefit private landowners might be difficult to justify. This explains why many property owners and developers lobby for TIF creation. In the final analysis, TIF might be accurately described as "revenue segregation" rather than as "value capture."[73]

Of course, a TIF project might lead to new development activity. Thus, in addition to taxes on increased land value, new development in a TIF district will be contributing additional revenues related to the value of new buildings and the taxable economic activities that occur in them. As mentioned previously, new buildings and economic activity will place demands on public goods and services. Tax revenues derived from new buildings and economic activity subject to a TIF will not be available to pay for these public goods and services until TIF termination―generally between 15 and 30 years from TIF inception. Some states have modified their enabling legislation to address this.

In Minnesota, the State statute governing TIFs mandates a test to determine whether a proposed TIF district satisfies Minnesota's but-for requirement:[74]

The previous section highlights concerns raised in articles that challenge the validity and equity of the but-for assumption in certain instances. Perhaps more importantly, due to the proliferation of TIFs in California and the perception that TIFs were depriving school systems of revenue, the California legislature took the following steps:

California eliminated TIFs in 2012. In 2014, California replaced TIFs with Enhanced Infrastructure Finance Districts (EIFDs). EIFDs are allowed to issue TIF-type debt. But EIFD debt is subject to more stringent limitations including:

So concerns exist about the but-for test that have generated academic studies and articles. And, in some places, like California, they have generated legislative reform. But what about litigation?

Unlike special assessments, exactions, or impact fees, TIFs do not impose a special or additional tax burden on properties that benefit from the government assistance projects. Thus, affected property owners are not motivated to challenge TIFs in court. To the contrary, property owners often support TIFs because, while paying taxes that they would pay in any event, a TIF dedicates funding for infrastructure projects that will provide them with a special benefit.[76] For this reason, there has not been as much litigation regarding TIFs as there has been regarding exactions and special assessments.

Nonetheless, some parties can be aggrieved by the creation of a TIF. Taxing districts (such as school districts) might believe that a TIF designation will deprive them of revenue for the life of a TIF. As mentioned earlier, this can be as long as 25 or 30 years. Therefore, a taxing district that could lose revenue might have both an interest in challenging the legality of a TIF as well as the resources for undertaking such a lawsuit.

Businesses might be motivated to challenge a TIF if they are located in a building that a TIF-subsidized redevelopment plan will demolish, particularly if they believe that they will not be able to survive the hiatus between demolition and redevelopment or if they believe that they won't be able to afford rents (or even be offered space) in the new development.

And, in some cases, a taxpayer might sue because they challenge a municipality's exercise of its taxing and spending powers pursuant to a TIF enabling statute. Generally, a person cannot sue the United States or an individual State simply because they are a taxpayer. However, taxpayer standing has been permitted to challenge county and municipal actions in certain instances. See the Malec case below.

The lack of litigation related to the but-for requirement for TIFs might indicate that:

There are not as many cases litigating TIFs as there are litigating special assessments and exactions. The research team was unable to find any TIF but-for litigation that had been decided by the U.S. Supreme Court. The cases summarized below are from State appellate courts.

In 1997, Illinois enacted the Tax Increment Allocation Redevelopment Act (TIF Act).[77] This act enables a municipality to eliminate blighted conditions within its boundaries by allowing the municipality to collect real property tax increment revenues from local taxing districts such as schools, park, sanitary and fire districts located in the TIF district and use these revenues to fund TIF development projects or other ancillary expenses in the TIF district.

The Village of Burr Ridge in Cook County, Illinois, created a TIF ordinance to facilitate the development of a vacant 85-acre parcel in 1998. After several experts had determined that the parcel did not qualify for TIF designation, the village hired a consultant to prepare a TIF eligibility study and redevelopment plan. The study found that pursuant to the TIF Act, growth and development of the parcel had been impeded by four blighting factors: diversity of ownership, flooding, obsolete platting, and tax delinquencies. Village counsel reviewed the study and informed the village that compliance with statutory requirements was marginal. A review board concluded that the parcel did not qualify for a TIF designation because it did not satisfy the statutory requirement for blight. Subsequently, the Village Board of Trustees enacted ordinances designating the parcel as a TIF district and approving the redevelopment plan.

The school district sued and claimed that the village's ordinances did not comply with the provisions of TIF Act because the village's legislative findings of blight made in the ordinances were erroneous and not supported in fact. [78] The school district claimed that if the TIF ordinances were implemented and the attendant redevelopment plan and project allowed to proceed, the school district and other overlying taxing districts would be irreparably harmed by the illegal and improper diversion of tax revenues from their taxing districts. The school district sought an order declaring that the ordinances were void as a matter of law and an injunction preventing the village from implementing the ordinances and selling bonds or undertaking any obligations or making expenditures pursuant to the ordinances.

With regard to motions for summary judgement, the village presented the eligibility study and its author. The school district presented an urban planning expert who relied upon the guidelines promulgated by the Illinois Department of Revenue as set forth in the 1988 TIF compliance manual (TIF Guide) that is commonly relied on by experts and courts in interpreting the TIF Act.

The trial court entered an order granting the school district's motion for summary judgment on the ground that the subject property did not contain any of the blighting factors necessary to qualify it for TIF designation under the TIF Act. The village appealed. The Appellate Court of Illinois affirmed the trial court's decision.

In order for the parcel to be deemed blighted, the village was required to establish that the growth and development of the property as a taxing district was impaired by a combination of two or more statutory blight factors. The blight factors are:

The trial court noted that deference is given to legislative findings. When reviewing the eligibility report, however, the court found no fact that established blight according to guidelines in the TIF compliance manual. The expert's assertion that the facts were sufficient did not make them so.

The trial court also found that development of the parcel would occur without the aid of TIF designation. The TIF Act requires a showing that the parcel "would not reasonably be anticipated to be developed without the adoption of the redevelopment plan."[80] This is the but-for test. The trial court was aware that development of the parcel had languished, but there was no evidence that this stagnation was attributable to any alleged blighting factors on the parcel but, rather, was due to the tax disparities between Cook and DuPage counties. The trial court also noted that, in spite of the large tax impediment, a 30-screen movie complex and a residential townhome development had been proposed for the parcel but had been denied by the Village Planning Commission after a large number of residents campaigned against the two projects.

This case highlights the importance of understanding and complying with the TIF-enabling statute and with official guidance documents. It also shows that, where a but-for requirement exists, there must be documentation to show compliance.

The City of Belleville procured a TIF eligibility study and redevelopment plan for several contiguous parcels comprising about 150 acres. Based on findings in the eligibility study, Belleville enacted ordinances creating a TIF district for the parcel for the purpose of creating new residences and a shopping center. In this case, Mr. Malec, a taxpayer, challenged the validity of the TIF ordinances and an accompanying economic incentive agreement for the shopping center portion of the parcel, contending that land that is being actively farmed should not qualify as "vacant" or "blighted" pursuant to the Illinois TIF Act.[81] In addition to the farming activity, there were five or so vacant structures on about 2.5 acres of the parcel and there was a risk of subsidence due to an abandoned, underground mine beneath the site. The roads adjacent to the site were also deemed to be insufficient for the daily traffic volume.

The TIF Act specifically exempts farmland from being classified as "vacant" for the purpose of satisfying the criteria for "blight." [82] However, the TIF Act was amended to make an exception for farmland that had been subdivided. The parcel had been subdivided over the years, although it remained under the control of one or two families who, by oral agreement, leased the land to a farmer. The economic incentive agreement statute, however, does not define "vacant" nor make an exception for farmland.

The trial court and appellate court agreed that the land was vacant for the purposes of the TIF act. They recognized that TIFs and economic incentive agreements were created for urban development and, in that context, land without structures is "vacant." They buttressed their decision based on the subdivision of the property. They noted that the TIF statute did not address whether blighted structures on a parcel constituted a significant or preponderant characteristic of the parcel. Therefore, they declined to insert any such qualification. They also agreed that the weight of the evidence showed that the land would not be developed for commercial purposes but for the TIF arrangement to remediate the abandoned mine to reduce the risk of subsidence.

The dissenting appellate judge investigated the amendments allowing farmland to be classified as vacant if the farmland had been subdivided. The judge noted that these amendments were "special legislation designed to validate specific pork barrel TIF projects in Illinois."[83] This judge argued that the presence of blighted buildings on 2.5 acres of the site did not permit the remainder of the site to be classified as "blighted." The dissenting judge noted that there was both residential and commercial development nearby that occurred despite the presence of abandoned mines and a risk for subsidence in those areas also. Therefore, the dissenting judge disagreed that the but-for test had been satisfied.

This case highlights the importance of statutory definitions and that the definition of "improved" and "vacant" property can be very different depending on whether the context is urban or rural. This distinction becomes meaningful and important particularly where rural and urban areas abut one another.

A shopping center in St. Louis (the City) sought to attract a Nordstrom store. To do so, the shopping center requested designation as a TIF to subsidize its redevelopment. St. Louis created a TIF Commission to investigate this request. The City also hired planning consultants who concluded that the area was blighted and met the "but-for" test contained in the TIF statute. The City solicited redevelopment proposals for the shopping center and the shopping center submitted the only bid. They proposed a redevelopment budget of about $212 million, of which $50 million would be provided in TIF subsidy. The City negotiated for a TIF subsidy of slightly less than $30 million. At this point, the TIF Commission and the Board of Aldermen held separate public hearings. The plaintiffs in this suit objected to the TIF designation at both hearings. [84]

The Board enacted several ordinances to adopt the redevelopment plan and authorize the TIF obligations. JG St. Louis West Limited Liability Company and others filed suit against City seeking a declaratory judgment that the four TIF ordinances were invalid, as well as seeking an injunction to prohibit the use of TIF in the redevelopment of shopping mall. Plaintiffs asserted the TIF ordinances were invalid because Board acted arbitrarily and unreasonably in declaring shopping mall to be a blighted area, in finding that shopping mall would not reasonably be developed without the use of TIF, and in approving the use of public funds for clearly private purposes.

The trial court held that City's four TIF ordinances were duly enacted and the actions of Board were not arbitrary nor induced by fraud, collusion, or bad faith. The appellate court agreed and confirmed the trial court's decision.

The Missouri statute defines "blighted area," as

An area which by reason of the predominance of defective or inadequate street layout, insanitary [sic] or unsafe conditions, deterioration of site improvements, improper subdivision or obsolete platting, or the existence of conditions which endanger life or property by fire and other causes, or any combination of such factors, retards the provision of housing accommodations or constitutes an economic or social liability or a menace to the public health, safety, morals, or welfare in its present condition and use.[85]

The Plaintiffs argued that the shopping center was the economic engine of St. Louis. It was an asset to St. Louis and, as such, could not be blighted or characterized as a liability. However, the board also found evidence that there were statutory blighting factors present that threatened the center's future success. Neither the trial court nor the appellate court sought to evaluate the board's reasoning. It was merely sufficient to see that the board raised debatable issues and consulted a wide variety of independent information sources including field investigations, records from local sources, interviews with local officials, and other independent studies.

The but-for test, contained in section 99.810, provides in pertinent part:

No redevelopment plan shall be adopted by a municipality without findings that: (1) The redevelopment area on the whole is a blighted area, a conservation area, or an economic development area, and has not been subject to growth and development through investment by private enterprise and would not reasonably be anticipated to be developed without the adoption of the redevelopment plan.

Here again, the court refused to evaluate the Board's reasoning. The court noted that the Board consulted different experts with different views and made a reasoned decision. No proof was presented that the Board's action was arbitrary or induced by fraud, collusion or bad faith. Therefore, the court refused to second-guess the Board's decision that the but-for test had been satisfied.

Finally, the plaintiffs argued that applying a TIF subsidy to a privately-owned and operated parking garage was not valid because a parking garage did not constitute a redevelopment cost pursuant to the TIF statute. The statute provides a substantial set of examples of redevelopment costs, and a parking garage is not included in those examples. However, the TIF statute states that the examples are illustrative and not intended to be an exhaustive or exclusive list. The court therefore refused to find that the parking garage was not a redevelopment cost that could be eligible for TIF assistance.

The City of Marion Illinois created two TIFs (TIF 1 and Illinois Center TIF). The TIF 1 area was about 1,400 acres and consisted of about 400 properties, many of which were blighted. The Illinois Center area was a 260-acre farm less than one-half mile from the interchange between Route 13 and Interstate Highway 57. Castel Properties sued Marion claiming, in part, that the TIFs were illegal because the finding of blight was not reasonable and because the TIFs did not satisfy the but-for requirement.[86]

The adopted redevelopment plan did not address or remediate the blighted conditions on TIF 1, and the farm was acquired and subdivided immediately prior to the TIF designation. These facts created an impression that the farm/Illinois Center TIF was attached to TIF 1 merely to imply blight by association. The fact that no action was taken to rectify the blight on TIF 1 implied that this action was more about developing the farm than about rectifying blight. As noted in the Malec case, farmland cannot be classified as vacant for TIF purposes unless it has been subdivided. The subdivision of the farm immediately before the TIF designation appeared to be an illegitimate attempt to qualify the farm as vacant for TIF purposes.

While deference to an elected body's determinations and findings makes overturning them difficult, it does not mean that a court must validate them if they are based on a lack of evidence or evidence deemed to be spurious.

The trial court agreed with the City of Marion regarding the designation of TIF 1 but agreed with Castel Properties about the illegitimacy of the Illinois Center TIF. The appellate court affirmed the trial court's decision. For both TIF 1 and the Illinois Center TIF, the courts showed deference to Marion's legislative findings. But, despite showing deference, the courts were not able to sustain Marion's findings regarding blight and but-for related to the Illinois Center TIF because Marion did not provide convincing evidence.[87]

Each State's statutory TIF requirements are unique.[88] Creating and administering TIFs will adhere to the substantive and procedural requirements established by the State TIF-authorizing statute and by local laws and procedures as well. If a State has created a how-to manual for TIFs and/or has an office responsible for overseeing TIF creation and administration, these provide authoritative sources for understanding legal and regulatory issues.[89]

State TIF-enabling statutes might include the following parameters for local implementing ordinances:

To the extent that these requirements exist in State law, localities typically hire consultants to conduct an eligibility study to ensure that the proposed TIF district boundaries satisfy mandated State criteria and to develop a TIF implementation plan. Working in concert with the local planning officials, civil engineers and budgeting officials, this plan should ensure that the proposed interventions are consistent with State law, that they satisfy any but-for requirement, and are consistent with local plans and zoning.

After the eligibility study and implementation plan have been completed, a public hearing is held in accordance with State law and/or local legislative procedures. Notice of the hearing is provided to the public generally and to property owners within the proposed TIF boundaries in particular. After the hearing and making any warranted change to the TIF plan, the TIF creation and implementation ordinance is drafted and subjected to the legislative process for enactment.

[57] Citizens Budget Commission, "Tax Increment Financing: A Primer," December 5, 2017. https://cbcny.org/research/tax-increment-financing-primer

[58] Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis the New School, "TIF Case Studies: California and Chicago," August 20, 2020 https://www.economicpolicyresearch.org/insights-blog/tif-case-studies-california-and-chicago .

[59] Benjamin Scheider, "City Lab University: Tax Increment Financing," October 24, 2019 at https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-10-24/the-lowdown-on-tif-the-developer-s-friend .

[60] See graphics and explanatory notes in the Appendix to this report.

[61] Cook County, Ill., "Chicago City Transit TIF Fact Sheet". https://www.cookcountyclerk.com/sites/default/files/pdfs/2017 Transit TIF RPM1 Fact Sheet_0.pdf. See also Bridget Fisher et al., "TIF Case Studies: California and Chicago"

[62] Sean McCarthy, Tax Increment Financing in Arizona, (ATRA) 2017, p 3. http://www.arizonatax.org/sites/default/files/publications/special_reports/file/tif_in_arizona.pdf

[63] Council of Development Finance Agencies. (2015). Tax Increment Finance State-by-State Report: An Analysis of Trends in State TIF Statutes. https://www.cdfa.net/cdfa/cdfaweb.nsf/ordredirect.html?open&id=201601-TIF-State-By-State.html. Accessed September 8, 2020.

[64] Not all state statues require the but-for test.

[65] Benjamin Scheider, "City Lab University: Tax Increment Financing." Bloomberg CityLab. October 24, 2019. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-10-24/the-lowdown-on-tif-the-developer-s-friend.

[66] Bridget Fisher et al., "TIF Case Studies: California and Chicago" Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis The New School, August 20, 2020. https://www.economicpolicyresearch.org/insights-blog/tif-case-studies-california-and-chicago

[67] Cook County, Ill., Chicago City Transit TIF Fact Sheet. https://www.cookcountyclerk.com/sites/default/files/pdfs/2017 Transit TIF RPM1 Fact Sheet_0.pdf

[68] Bridget Fisher et al., "TIF Case Studies: California and Chicago." https://www.economicpolicyresearch.org/insights-blog/tif-case-studies-california-and-chicago

[69] For an elaboration, see discussions about development impact fees, especially FHWA, Value Capture Implementation Manual, Section 4, "Developer Contributions." https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ipd/value_capture/resources/value_capture_resources/value_capture_implementation_manual/ch_4.aspx

[70] Michael Dardia, Subsidizing Redevelopment in California, (Public Policy Institute of California) January 1998, p xiii. https://www.ppic.org/content/pubs/report/R_298MDR.pdf

[71] Alan Mallach, The Divided City: Poverty and Prosperity in Urban America, Island Press 2018, p 164.

[72] Present value for a perpetual stream of income or expense = Annual income (or expense) / interest rate. Thus, a perpetual payment of $2 has a present value of $2/.05 = $40. So if a landowner receives $100 in publicly created land value and must pay an annual $2 fee (the present value of which is $40), then the landowner is receiving $100 minus $40 (the present value of tax payments), leaving a $60 (60 percent) windfall gain.

[73] NCHRP Report 873, "Guidebook to Funding Transportation Through Land Value Return and Recycling," p 17. http://www.trb.org/Main/Blurbs/177574.aspx. See also David Merriman, "Improving Tax Increment Financing (TIF) for Economic Development," (Lincoln Institute of Land Policy) 2018, p 12. https://www.lincolninst.edu/sites/default/files/pubfiles/improving-tax-increment-financing-full.pdf

[74] Minnesota House Research Department, "The But-For Test," https://www.house.leg.state.mn.us/hrd/issinfo/tif/butfor.aspx, accessed Oct. 25, 2020.

[75] Bridget Fisher, Flávia Leite and Lina Moe, "TIF Case Studies: California and Chicago," Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis The New School, August 20, 2020. https://www.economicpolicyresearch.org/insights-blog/tif-case-studies-california-and-chicago

[76] Sean McCarthy, Tax Increment Financing in Arizona, (ATRA) 2017, p 2. http://www.arizonatax.org/sites/default/files/publications/special_reports/file/tif_in_arizona.pdf

[77] Tax Increment Allocation Redevelopment Act (TIF Act) (65 ILCS 5/11-74.4-1 et seq. (West 1994))

[78] Board of Education, Pleasantdale School District No. 107, Cook County Illinois v The Village of Burr Ridge, 793 N.E.2d 856, 341 Ill. App.3d 1004, 276 Ill. Dec. 97 (Ill. App. 2003)

[79] 65 ILCS 5/11-74.4-3(a) (West 1994).

[80] 65 ILCS 5/11-74.4-3(n)(J)(1) (West 2002).

[81] Malec v. the City of Belleville, 943 N.E.2d 243, 407 Ill.App.3d 610, 347 Ill.Dec. 953 (Ill. App. 2011)

[82] Tax Increment Allocation Redevelopment Act (TIF Act) (65 ILCS 5/11-74.4-1 et seq. (West 1994))

[83] Malec at 347 Ill.Dec. 984, 943 N.E.2d 274.

[84] JG St. Louis West Limited Liability Company, et al. v. City of Des Peres and West County Center, LLC, ED77037, Missouri Court of Appeals Eastern District, 41 S.W.3d 513 (Mo.App. E.D. 2001)

[85] Section 99.805(1) RSMo 1994

[86] Castel Properties, Ltd. v. City of Marion, 631 N.E.2d 459, 259 Ill.App.3d 432, 197 Ill.Dec. 456 (Ill. App. 1994)

[87] In a Minnesota case, Walser Auto Sales v. City of Richfield, 635 N.W.2d 391 (Minn. App. 2001), a consultant used dubious methods and erroneous procedures to find "blight" within a proposed TIF district. The appellate court concluded that the municipality's desired result determined the conclusion of the blight evaluation and analysis. On this and other counts, the case was remanded to the trial court for further review and adjudication.

[88] For citations to individual State laws authorizing TIF, see https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ipd/value_capture/legislation/tax_increment_financing.aspx .

[89] Minnesota has extensive online materials related to TIF formation and implementation at https://www.house.leg.state.mn.us/hrd/issinfo/tifmain.aspx?src=21 . Montana has a TIF manual available at https://leg.mt.gov/content/Committees/Interim/2017-2018/Revenue-and-Transportation/Meetings/Sept-2017/tif-manual-2014-cornish.pdf .

[90] Studies indicate that TIFs have often been used in areas that wouldn't be considered as "blighted." In some cases, TIF laws have been amended to eliminate the blight requirement. See David Merriman, Improving Tax Increment Financing (TIF) for Economic Development, (Lincoln Institute of Land Policy) 2018, p 7.

[91] Id., pp 15-16. Studies indicate that the but-for test has often been construed very loosely.