TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF FIGURES

LIST OF TABLES

There are currently two relatively new but effective VC techniques in the United States that are based on negotiated contracts–development agreements (DA) and community benefits agreements (CBA)–that provide more flexible and less litigious means to VC when compared to other existing techniques. Each serves very different and specific needs for infrastructure funding. The recent proliferation of these techniques has occurred rather quickly and with little debate, in part due to their significant perceived benefits (Selmi 2011). This chapter discusses the DA and the next chapter (Chapter 3) explores the CBA.

A DA is a contract between a local jurisdiction (usually a city) and a property owner (usually a developer) (see Sidebar 2.1). The agreement sets the standards and conditions that govern the development of the property. It not only provides certainty to the developer that his or her project will be isolated from changes in the jurisdiction's zoning laws over the course of development, but it also contracts the developer to provide benefits to the city, such as infrastructure improvements, public pen space, or monetary payment into funds, including "in lieu" fees (e.g., impact or linkage fees), in exchange for that certainty.

"DAs are contracts negotiated between project proponents and public agencies that govern the land uses that may be allowed in a particular development project. Although subject to negotiation, allowable land uses must be consistent with the local planning policies formulated by the legislative body through its general plan,5 and consistent with any applicable specific plan.

Neither the applicant nor the public agency is required to enter into a DA. When they do, the allowable land uses and other terms and conditions of approval are negotiated between the parties, subject to the public agency's ultimate approval. While a DA must advance the agency's local planning policies, it may also contain provisions that vary from otherwise applicable zoning standards and land use requirements.

The DA is essentially a planning technique that allows public agencies greater latitude to advance local planning policies, sometimes in new and creative ways. While a DA may be viewed as an alternative to the traditional development approval process, it is commonly used in conjunction with it. It is not uncommon, for example, to see a developer apply for approval of a conditional use permit, zoning change and DA for the same project."

(Source: Larsen 2002)

DAs are voluntary, negotiated, and provide legally binding assurances for both local governments and developers. As discussed later, many local governments and developers have used this technique to create win-win opportunities, especially when dealing with uncertainties in the regulatory environment. Through DA, the local government is afforded greater latitude in advancing local planning policies and greater flexibility in imposing conditions and requirements on the proposed development projects, while the developer is afforded greater assurance that once the project is approved, it can be built.

First introduced in California in the 1970s, DA was in part triggered by the new requirements for "vested rights" set by the Avco case. A vested right is the property owner's irrevocable right to develop his or her property that cannot be changed by future growth restrictions or other regulatory reversals. The California Supreme Court ruling in Avco Community Developers v. South Coastal Regional Commission (1976) resulted in more restrictive requirements for property owners, whereby vested rights are granted only after they obtain all building permits and make substantial investments on their development project. The Avco ruling left developers much more vulnerable to changes in requirements and other discretionary approvals. In an attempt to reduce the impact of Avco, the California legislature subsequently established the Development Agreement Law in 1979 (Government Code §65864 et seq.) (Barclay and Gray 2020) (see Sidebar 2.2).6

In exchange for large-scale infrastructure provisions, DAs make it easier for developers to obtain vested rights that reduce developer risk and increase investor and creditor confidence. DAs must conform to local general plans and they are often processed concurrently with general plan amendments. They are also often accompanied by specific plans that establish a special set of development and zoning standards for the project. From the local government perspective, DAs can (1) facilitate the general planning process to help achieve long-range planning goals, (2) help secure commitments for infrastructure, (3) provide public benefits not otherwise obtainable under the regulatory takings doctrine, and (4) help avoid administrative and litigation expenses (Selmi 2011). In contrast, the popularity of DAs in the developer community suggest that developers highly value the certainty afforded by vested rights and are willing to pay a high price to acquire this certainty.

Zoning ordinances can be changed at the will of the governing body, or by the people of the city through ballot initiatives. Thus, a project that was agreed upon and permitted one year could be required to dramatically change to meet legislation passed another year. "Vested rights" is a legal doctrine establishing when a project would be protected from further actions of the city government, such as changes in the zoning code. The issue is, of course, when does the vesting take place?

The Development Agreement Law was first enacted in 1979 in California, in response to the Avco Community Developers, Inc. v. South Coast Regional Commission decision (17 Cal. 3d 785, 1976). The Avco case involved a large development in Orange County, California, some of which was in the coastal zone. Under the California Coastal Act of 1976 (CA PRC Sec. 30000-30265.5), the developer had to obtain a permit from the Coastal Commission unless it had obtained a building permit. In this case, the developer had secured a final subdivision map and a grading permit, but did not have a building permit. The developer had already spent a great deal of money on the site.

The court ruled that the developer's project was indeed subject to the Coastal Act's additional requirements and restrictions, reaffirming the rule that property owners can acquire a vested right to complete construction only after they have performed substantial work and incurred substantial liabilities in good faith reliance on a permit issued by regulatory authorities. Only at that point can a project be completely free of new restrictions.

The result in Avco created great consternation in the development community, which lobbied the Legislature to create a mechanism that would allow developers to know earlier on in the process what requirements would apply to their projects. The Development Agreement Law is a result of this effort.

(Source: Barclay and Gray 2020)

DAs are negotiated and, because each DA is unique and based on a particular development site and/or project, they vary widely in content and the specific terms negotiated. In general, DAs contain the following basic elements:

A number of considerations would be taken into account when drafting a DA. For efficiency, a local agency might start with a standard agreement that has already been reviewed and approved by the agency's attorney. It is also helpful for the assigned DA negotiators to have reviewed:

When drafting the agreement, these steps help those involved to think ahead about potential implementation issues that need to be negotiated to protect the public's interests. In the final analysis, a well-drafted DA would accurately capture the deal points negotiated by the parties, and anticipate and address potential problems that may arise during implementation of its terms.

Some of the key provisions to be covered in a DA include (see Sidebar 2.3 for additional details on key provisions and Appendix A for a sample DA template):

Source: Larsen, D. J. (2002). Development Agreement Manual: Collaboration in Pursuit of Community Interest. Institute for Local Self-Government, Sacramento, CA.

From a local agency standpoint, the DA implementation process begins with the local agency's procedures for DAs.7 A well-crafted set of DA procedures would provide a useful road map to local staff and others in shepherding a DA through the approval process. Such procedures would also be useful for considering any amendments to and termination of a DA. Important parts of the process would also include the notice and hearing process, as well as mechanisms for providing decision-maker input.

Once the procedures are in place and the parties enter into negotiations for a specific development project, the developer and the local government would both work with legal counsel to develop and execute a contract that binds all parties. During the negotiation of such an agreement, planning staff would work closely with their land use attorney, appointed and elected officials, and the public to answer the following key questions:

By preparing in advance a negotiating framework and adopting basic ground rules in how negotiations are conducted, the parties would be able to create a negotiating environment that increases the likelihood of reaching consensus. Each party should be clear on their and the other party's priority issues going into the negotiations so that each priority can be addressed early on. For local agencies, these priority issues often include:

Once the preparation is complete, the key DA implementation steps could include the following (see Sidebar 2.4 for more details):

Establishing Purpose/Findings. A goal statement such as "to promote the community's needs and receive greater community benefits than otherwise can be achieved through the land use regulatory process" can be helpful in setting the tone for negotiations, so that both parties have realistic expectations going into the negotiations. Where available, reference to the DA statute can be helpful in this step.

Application Process. An application form specifying the type of information an agency needs to process the DA request ensures that the agency receives all the information it needs in a timely manner. Having a readily available form saves staff time in reviewing DAs. It also provides greater assurance that the agreement will cover all of the agency's needs, including all requirements pertaining to environmental analysis. Some agencies charge fees to process applications.

Public Hearing and Notices. The DA law, if established at the State level, may require a notification and public hearing by both the planning agency and by the local agency's governing body before a DA is approved.

Recordation and Other Post-Approval Steps. After a DA is approved, the clerk of the governing body must (a) record a copy of the DA within a pre-established time period (e.g., 10 days in California) from the entity's entry into the agreement, along with a description of the land subject to the DA, and (b) publish the ordinance approving the DA. Failure to satisfy the publication requirement in a timely manner prevents the ordinance from taking effect or being valid.

Amending the DA. After a DA has been signed, it may be amended only by mutual agreement of parties. Most DA procedures require amendments that are initiated by the developer to follow the same process as the initial application. For local agency-initiated amendments, the procedures usually require notice to the developer and provision of information about the process that the agency will employ.

DA Accountability. In California, the DA law requires local agencies to include at least an annual review of the developer's compliance with the delineated responsibilities. The review must require the developer to demonstrate good faith compliance with the terms of the DA. If a local agency finds, based on substantial evidence, that such compliance has not occurred, the agency may modify or terminate the DA. In addition, the DA law provides that the DA is "enforceable by any party." A DA typically contains provisions specifying procedures for notice and termination in the event of a default by either party.

Source: Larsen, D. J. (2002). Development Agreement Manual: Collaboration in Pursuit of Community Interest. Institute for Local Self-Government, Sacramento, CA.

Despite DAs' significant benefits, some developers avoid using them because of the potential for expensive project requirements, whereas some local agencies avoid them because of the limitations that they impose on their ability to respond to a changing regulatory environment. Nevertheless, the latitude afforded by DAs to advance local agencies' planning objectives–sometimes in new and innovative ways, as mentioned, as well as lowering developer risks and enhancing predictability–makes the DA a useful and viable technique in service to the community, including finding critical funding sources for much needed public improvements. For both parties, DAs can involve a great deal of time and energy to negotiate and implement. Accordingly, it is important at the outset to carefully evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of using a DA in each specific circumstance (see Sidebar 2.5).

DAs allow communities a degree of flexibility not otherwise available under existing local zoning regulations. Advantages include:

Critics of development agreements claim that they circumvent traditional development review processes. Other challenges include:

(Source: CDLA 2016)

In essence, DAs have three defining characteristics: (1) They allow greater latitude than other methods of approval to advance local land use policies, (2) they allow public agencies greater flexibility in imposing conditions and requirements on proposed projects, and (3) they afford project proponents greater assurance that once approved, their projects will be built. Although these characteristics can be advantageous and offer significant VC opportunities, they can also present important challenges.

Opportunity–Ability to Better Implement Innovative Planning Policies

For local agencies, literal compliance with individual zoning ordinances can sometimes thwart promotion of the larger policies underlying the general plan. The general plan, for example, may encourage the existence of open space but the applicable zoning district does not allow sufficient density for residential units necessary to accommodate an open space component. In the past, DAs enabled creative (and, at times, award-winning) land use projects because they can facilitate projects that would not have been allowed under otherwise applicable zoning regulations. The approval of creative land use concepts, and the resulting project constructions, have advanced the state of urban planning and allowed local agencies to better combat the visual and aesthetic impacts of "cookie-cutter" development approaches (CDLA 2016).

As long as the project is consistent with the local planning policies formulated by the legislative body through its general plan, DAs can provide greater latitude to incorporate land use concepts and components that are tailored to address particular community concerns. Such tailored land use concepts can also reflect various ways to maximize VC opportunities. The ability to vary from strict adherence to otherwise applicable zoning provisions can help ensure that the local agency's land use policies are being advanced, in sometimes new and innovative ways. These advantages are shared by the local agency and the developer alike.

Limitation–Potential to Promote Bad Planning

From the local agency's perspective, if a developer is willing to provide a significant level of public amenities through a DA, it may feel pressured to compromise its planning standards in a manner that could reduce the quality of life in the community. The pressure to compromise may be especially great in the case of a "friendly developer" who has a popular presence in the community. From the developer's perspective, it is possible that the legislative body may decide to put additional requirements in the DA that could limit the property uses that are already allowed and appropriate from a conventional planning perspective.

The planning policies and objectives that have been embraced by the community through the general plan adoption, together with any applicable specific plan, would be an integral part of the DA negotiations. By identifying applicable planning policies early on and continuing to use them as yardsticks in determining what land uses are appropriate, the parties would be able to avoid unacceptable compromises when negotiating DAs.

Opportunity–More Developer Requirements Without Statutory/Constitutional Constraints

For many years, local agencies have been facing legal constraints that directly affect their ability to regulate development. In particular, voter initiatives that limit local agencies' revenue raising authority (e.g., property tax) and questions associated with these initiatives have created legal uncertainties. As a result, local agencies have increasingly required developers to bear the costs to the community associated with their development projects. As mentioned earlier, many agencies have adopted impact fees, for example, to require developers to pay the costs of infrastructure, facilities, and public services required to service their projects. This has sometimes resulted in costly legal challenges.

A local agency might avoid these legal constraints and uncertainties by entering into DAs, where the developers agree to the fees and other requirements. Once the DA is executed, the developer waives his or her right to challenge the fairness or appropriateness of a particular requirement. As such, DAs are generally exempt from the essential nexus and rough proportionality tests associated with other traditional forms of developer exactions (unless the DA process uses inappropriate leverage to impose conditions or achieve developer concessions). The fact that the DA is recorded as a local ordinance also provides a convenient mechanism that could be used for binding future owners to the requirements and obligations created by the agreement.

With these constraints removed, local governments are often well-positioned to negotiate larger concessions from developers that exceed what they would have obtained otherwise. For example, they can ask the developer to agree to (1) finance public facilities and improvements without the specter of a regulatory takings claim, (2) construct a new school without fear that school facility fee limitations will be invoked, (3) complete facilities and improvements earlier in the development process (resulting in needed infrastructure and facilities being put in place prior to or concurrent with the development, reducing the development's impact on existing facilities or services), and/or (4) pay additional fees to protect the agency and existing residents from any budgetary impacts associated with the development.

Limitation–Unrealistic Expectations Can Make Project Infeasible

In the early phases of projects, developers face a myriad of issues (e.g., land availability, financing, market considerations, and various Federal, State and local regulatory requirements) that present challenges to devising financially feasible development projects. In projects where a DA is considered, some developers may choose to abandon the DA altogether in the midstream to avoid the risk of discovering after months of negotiations that the local agency expects the developer to construct an expensive public amenity, such as a school or park, that overrides any benefit he or she can derive from the DA. As mentioned in the DA implementation process, one way to avoid this problem is to discuss the parties' expectations at the outset as a prelude to DA negotiations, thereby allowing each party to assess early on whether a DA will meet each party's needs.

Opportunity–Fewer Surprises After Project Approval

As mentioned, development projects must meet the regulatory standards that are in effect at each stage of the development process until their projects become "vested" after substantial amounts of time and money have been invested. In DAs, developers receive vested rights immediately upon the execution of the agreement, because a DA "freezes" applicable local land use regulations for the proposed project.

From a developer's perspective, the added certainty associated with receiving vested rights can be extremely valuable, especially for large projects that require securing financing for large upfront costs. The added certainty is also critical in situations where a potential ballot measure or a change in the makeup of the legislative body majority could adversely affect the project.9 There are a few limits to this assurance, such as a finding that further analysis is required for final environmental clearance.10 Final approval of a DA also cannot prevent the application of State or Federal regulations.

Limitation–Relinquishing Local Agency's Regulatory Control

DAs can limit the local agency's ability to respond to a changing regulatory environment. If the agency's planning regulations are in need of review or updating, DA terms and conditions may not sufficiently protect the community's interests. Since changes to the agreement require mutual consent, it may be difficult to add conditions or requirements later, should the agency identify the need to do so after the agreement is entered into. DAs place a premium on the agency's ability to identify all of the issues presented by a project at the outset of the DA negotiations.

From the developer's perspective, the DA obligations are also locked in, without any flexibility to respond to changes in the real estate market and the resulting project economics. As mentioned, DA's protection from regulatory change is limited to local regulations. In general, DAs must be modified if necessary to comply with subsequently enacted State or Federal requirements, which could prevent or preclude compliance with the provisions of the DA.11

Other practical criticisms against DAs have included the need for greater public participation and transparency. Also, recognizing the high value placed on DAs' vested rights, especially when the DA term is long (sometimes as long as 30 years or more), developers often sell the projects before they are built, bringing in new owners who may want changes in the original development program linked to the DA. As a result, the lack of a framework for renegotiation (and appropriate terms and conditions for amendments, extensions, and terminations) can be an area of concern (Fulton and Shigley 2012).

In his article "The Contract Transformation in Land Use Regulation" related to DA, Selmi (2011) also raises questions about reconciling the public law of land use with the private contract law. He identifies six potential long-term effects 12 associated with the use of a contract-based model such as a DA and suggests the need for further legislative oversight of DAs and other land use-based contracts.

DAs have a wide range of applications in terms of project type, size, location, and the extent to which public improvements are covered. As mentioned, because DAs can be used to advance overall land use planning policies, they have been found to be most effective for large-scale development projects involving multiple developers implemented in multiple phases over a long time. As such, DAs have been particularly popular in rapidly growing areas where significant changes in land uses have taken place. In California, for example, DAs were the cornerstone of the Foothill Circulation Phasing Program, often cited as a successful DA example, where 19 developers in Orange County agreed to contribute a substantial portion of more than $250 million for public improvements in exchange for the vested right to build their projects and create new bedroom communities (Irani et al. 1991).

In terms of direct linkage to transportation infrastructure, DAs can be a useful technique in capturing and monetizing anticipated property value increases from new developments along planned major highway corridors or transit-oriented developments (TODs). These capital project-induced DAs can be at corridor level involving multiple jurisdictions or at an individual intersection or station involving a single jurisdiction. In most cases, however, DAs are driven by major real estate development projects initiated by developers and include provisions for additional infrastructure capacity needed for their projects. Public improvements for a DA, for example, could include (for both capital and operations and maintenance (O&M)) new access roads, existing street widening and other improvements, intelligent transportation systems (ITS) at intersections, and other public services (e.g., fire, police, traffic, telecommunication) needed for the development project.

Although the number of States that authorize the use of DAs is still limited, their use has been expanding rapidly where they are allowed. Since its introduction in the 1970s, the use of DAs in California has evolved greatly. Especially for large projects requiring significant infrastructure improvements, DAs are now used not only to obtain developer contributions but also as a means to engage other VC techniques (such as TIF and SAD) to ensure all necessary future funding sources for these improvements are clearly delineated at the project outset. One such case example–the SoFi Complex DA between the City of Inglewood and Hollywood Parkland Co.–is described in Section 2.5.2.

Beyond California, many cities in Washington State have been using DAs in a wide variety of applications involving both small and large complex projects and ranging from cleanup and redevelopment of a contaminated riverfront site to a 1,200-acre phased, master-planned community that includes affordable housing provisions and significant open space (MRSC 2016). Various DA applications used in Washington (presented in Table 2) provide a good representation of different ways DAs can be used by local governments to obtain VC-related funding for public improvements, including those for local transportation infrastructure.

In addition to general public improvements, DAs are sometimes used to serve a very specific public benefit purpose. In Colorado, for example, LaPlata and Eagle counties have used DAs specifically for hazard mitigation purposes to guarantee reduction in risk from project-related hazards by specifying provisions not required by existing land development regulations, including site development standards for conservation and long-term maintenance needs (CDLA 2016).

Finally, DAs are long-term by design and sometimes require amendments as market conditions change. A developer, for example, may need to extend or terminate an agreement if he/she fails to secure financing or wants to do something entirely different with the property. Either party can also seek termination if the terms of the agreement have not been met. Specific case examples pertaining to DA amendments, extensions and terminations can also be found (see MSRC 2016).13

Table 2. Range of Potential DA Applications–Washington State Example

DA Parties |

Year/Term |

Project Scope (Size) |

Public Improvements Covered |

VC Technique Used* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

City of Bellevue and WR-SRI 120th LLC |

2009/5 yrs |

36-acre, $1B mixed-use urban revitalization linked to light rail (Sound Transit East Link) (Small) |

Park and recreation space; transportation and other public improvements |

Impact fees |

City of Issaquah and Grand Glacier LLC |

2007/20 yrs |

TOD area development for zero-energy & affordable housing; sustainable development demonstration project (Small) |

Municipal facilities and services (transportation, fire, police, general gov't and parks) |

Impact fees |

City of Redmond and Microsoft |

2007/20 yrs |

27-acre, 550,000 sq. ft. development for secondary Microsoft campus with density transfer needs (Small) |

Multi-modal access, intersections, traffic signals, internal roads, transportation demand management, utilities, water/sewer, storm water |

Transport. impact fees |

Snohomish County and Community Transit |

2009/5 yrs |

Swift BRT

project with |

Transportation and other public improvements/mitigations |

Impact fees |

City of Black Diamond and BD Village Partners L.P. |

2011/15 yrs |

1,200-acre, phased, mixed-use, master-planned community development (Large) |

Transportation and other public infrastructure; park and open space, recreation facilities; affordable housing |

TDR, impact fees |

City of Des Moines and SSI Pacific Place LLC |

2007/15 yrs |

Redevelopment of a blighted area into new urban community with Sound Transit regional light rail link (Large) |

Transportation and other public infrastructure |

Traffic impact fees |

City of

Everett |

2009/20 yrs |

Cleanup and redevelopment of riverfront brownfield sites into mixed use (Large/Complex) |

Transportation and other public infrastructure |

Transport/school impact fees |

City of Issaquah and Lakeside Industries, Inc. |

2012/28 yrs |

123-acre, master-planned, urban village involving reclamation of mineral resources site & hillside development (Large/Complex) |

Transportation and other public infrastructure, affordable housing |

Impact fees and other cost sharing |

City of

Tukwila |

2009 |

512-acre, 10 million sq. ft. master-planned, mixed-use, adjacent to regional shopping mall (Large) |

Transportation and other public infrastructure; park and open space |

Impact fees |

Source: DA for each of these cases can be found at: http://mrsc.org/Home/Explore-Topics/Planning/Land-Use-Administration/Development-Agreements.aspx (MRSC 2016)

* In addition to the VC technique identified, in several cases, developers also provided additional cost-sharing measures and/or in-kind contributions to fund the needed public improvements.

As mentioned, a DA can be used to implement multiple VC techniques other than developer exactions. One such example is the DA between City of Inglewood and Hollywood Park LLC. Hollywood Park is a $5-billion, 300-acre master-planned community in the heart of the City of Inglewood. The project is anchored by the new SoFi Stadium, home to L.A. Rams and L.A. Chargers professional football teams, and consists of a major entertainment complex and mixed-use retail center. It is located only 3 miles from Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) and also close to three Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transit Authority (LACMTA) (commonly referred to as "LA Metro") transit stations. The City is currently planning an automated people mover (APM) system to connect the stadium complex with one of the Metro stations and looking to one or more VC techniques as a potential funding source for the APM. In addition to engaging multiple VC techniques as part of the DA, pre-planning and other implementation steps taken by both parties leading to the final approval also contributed to the success of the DA.

Project Components. L.A. Stadium and Entertainment District (LASED) includes:

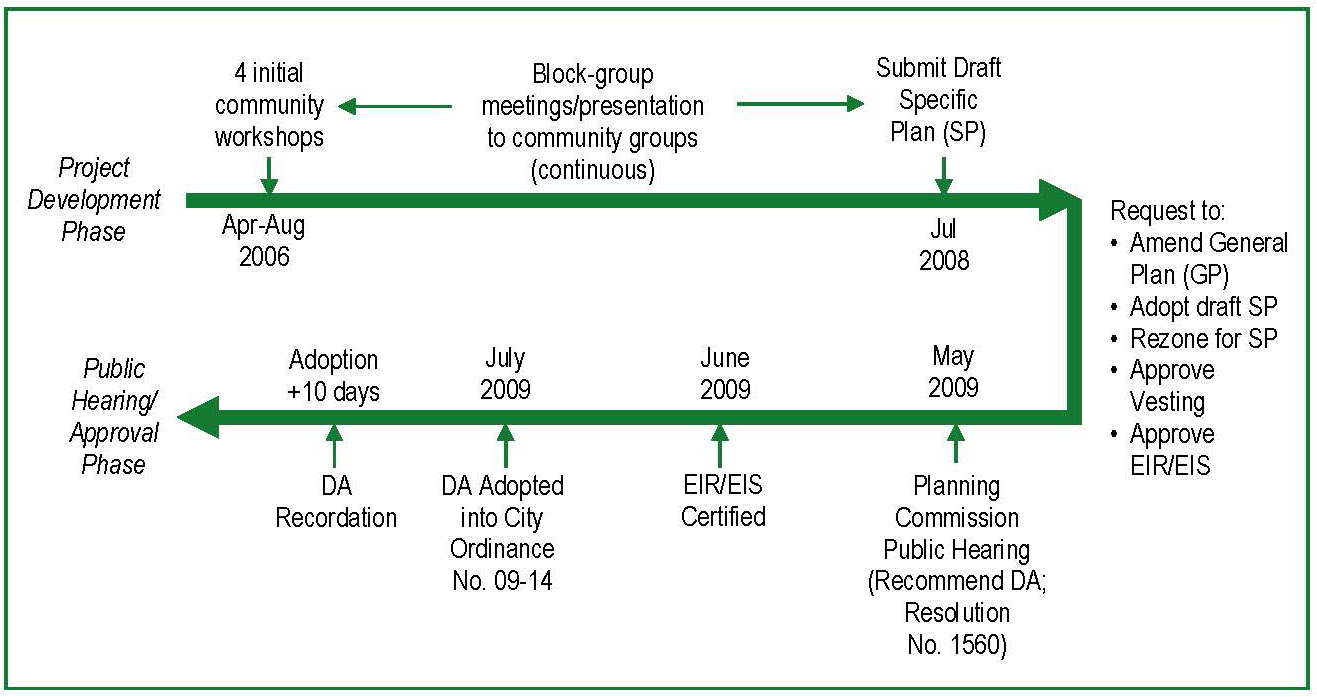

Project Development and DA Implementation Timeline: See Figure 1 below. In addition, post-adoption annual reviews are also included in the DA provisions.

Figure 1. DA Planning and Development Process (Source: Inglewood 2009)

DA Term. 15 years with an option to extend for another 5 years.

Public Benefits and Improvements. The DA identified the following as the primary public benefits that the developer would provide to the City and the community:

Financing Plan and VC Techniques Used. Public improvement construction and park maintenance costs to be paid by:

As needed, additional impact fees and other exactions payable by the developer to be adopted after the DA approval/adoption date, not to exceed $10 million.

Others–Costs in connection with DA annual reviews and

other administrative costs to be paid by the developer.

6Subject to general contract law, the use of DAs does not necessarily require State DA legislation. However, to fully capitalize on DAs' advantages, such as the exemptions from essential nexus/rough proportionality tests and vested rights, State DA legislation would be required.

7Although DAs become part of local ordinance once approved, DA implementation process and procedures, if established at all, are considered more as general guidelines rather than local regulations or ordinance.

8In California, for example, DAs are subject to voter referenda where voters must file their opposition within 30 days after the local agency's approval of the DA (prior to the final adoption) in order to put the DA approval issue on the ballot. Once the 30-day period is over, the developer can safely assume that the project will not be affected by any future ballot measures. The adoption of a DA can also be challenged in California but the challenge must be within 90 days of the adoption.