TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF FIGURES

LIST OF TABLES

The implementation of a CIP can be divided into two major steps. The first is the development of the program, and the second is its administration. Together, these two steps constitute the capital improvement programming process. As noted in the introduction, the CIP is a powerful tool in the implementation of a community’s comprehensive plan.[xv]

The CIP coordinates a community’s plans with its financial capacity and the development of its physical infrastructure to provide a blueprint for planning the community’s capital expenditures.9 This coordination requires the implementation of a CIP that complements a community’s existing comprehensive plans, as well as other subordinate system-specific plans that a community may have, such as a transportation or mobility plan. In the case of transportation, it is imperative that a community’s plans and CIPs are well coordinated with relevant metropolitan or regional transportation plans and programs to ensure eligibility for State and Federal funding sources for its projects. These different plans and programs are the essential guiding documents that should be considered in the implementation of a CIP.

This chapter reviews these interrelated guiding documents, highlighting their influence on the implementation of a community’s CIP. This chapter also provides an overview of the development and administration processes involved in the implementation of a CIP, and an overview of the timing of preparing a CIP vis-à-vis the local government’s annual budget process.

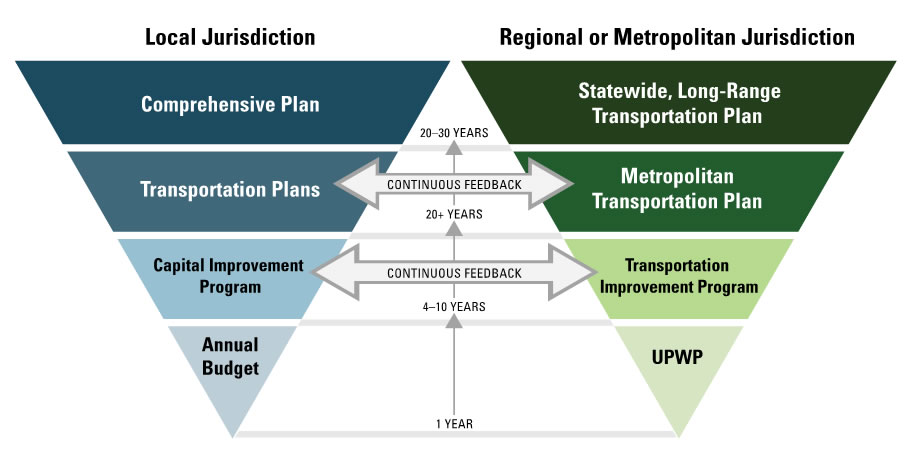

A review of the various guiding documents is critical to ensuring that the CIP considers projects that are aligned with adopted plans (and avoids projects that may contradict them) and to properly identify funding sources and constraints. This section identifies these guiding documents and discusses their characteristics, interrelationships, and their relationship with the CIP. Figure 2 shows these documents using a vertical and a horizontal scale, with a focus on the transportation element guiding documents. The vertical scale consists of four levels and illustrates the top-down, general to specific influence of the different guiding documents on one another, and on the CIP. Horizontally, the scale consists of two levels—the local jurisdiction level and the regional or metropolitan level. Figure 2 illustrates the interrelationships between a local jurisdiction’s guiding documents and counterpart regional or metropolitan transportation plans and documents, and their combined influence on the development of the CIP.

Figure 2. CIP Guiding Documents

Comprehensive plans are developed by local governments. They provide guidance and recommendations to achieve the community vision of the region over the next 20 to 30 years. Comprehensive plans are often divided into elements, with transportation being one of them. At the second level of the local guiding documents scale, some communities have a local transportation plan. Local transportation plans typically share a vision for a horizon of 20 years or more focused on a transportation mode (e.g., bicycle, transit, freight, multimodal) or in a specific location (e.g., a district or a neighborhood), and they are not required to be fiscally constrained. The CIP and its transportation element sit below these documents at the third level of the local document scale. The CIP supports the implementation of the comprehensive and local transportation plans by means of a prioritized list of transportation projects for the community over a period of 5 to 10 years. The CIP, in turn, is used to develop a recommended capital budget. Capital costs in the first (or current) year of the CIP become the recommended annual capital budget to be adopted by the local government. The CIP also contains information regarding the impact of capital projects on the operating budget. This information, in turn, is used along with the capital costs to develop the annual budget.

At the regional or metropolitan level, transportation guiding documents are governed by Federal regulations and have a structure that has some parallels with the local guiding documents, as shown in Figure 1.[xvi]

The[xvi] These guiding documents are critical to the development of the CIP in that the eligibility of its transportation projects for State and Federal transportation funding sources is tied to the projects being

part of the adopted regional plans. At the top level of the regional structure are the statewide long-range transportation plans (SLRTPs), which are developed by State departments of transportation (DOTs). At the second level in the vertical scale, in urban areas with a population of 50,000 or more and that are included in a planning area of a metropolitan planning organization (MPO), are the metropolitan transportation plans (MTPs).[xvii] MTPs are developed and adopted by MPOs and consist of a set of long-range and short-range strategies that allow the development of an integrated and intermodal transportation system in a metropolitan region. MTPs have a time horizon of at least 20 years and are required by Federal law to be fiscally constrained.[xviii] Similarly, areas with a population of less than 50,000 where a regional transportation planning organization (RTPO) has been designated have a regional long-range transportation plan (LRTP) that plays the same role as the MTP as a guiding document for local communities to develop their CIP. The MTPs and regional LRTPs are consolidated by each State DOT into the SLRTP.

At the third level of regional guiding documents are the TIPs developed and adopted by MPOs, RTPOs, and State DOTs. These TIPs are consolidated at the State level by the State DOT into an STIP. Similar to the role that a CIP plays at the local level, a TIP allows the implementation of an MTP (or a regional LRTP) by means of a prioritized list of transportation projects. TIPs and STIPs cover a period of 4 years at a minimum and must be updated at least every 4 years.

Finally, at the fourth level is the Unified Planning Work Program (UPWP), which identifies work proposed for the next 1- or 2-year period, indicating which entity (i.e., MPO, State DOT, public transportation operator, local government, or consultant) will perform the work, create a schedule, propose funding, and provide a summary of amounts and sources of Federal and matching funds. It is critical for a local government that the development of its CIP is closely coordinated with the regional planning processes and documents, particularly the TIP, and subsequently for the local annual budget to be synchronized with the UPWP. This will help ensure that the CIP transportation projects that are expected to rely on State or Federal transportation funds are indeed reflected in the regional guiding documents, so the local government is eligible to access those funds exactly when they need them. This is illustrated in Figure 1, which shows the continuous feedback processes between a local government’s CIP and its corresponding metropolitan (or regional) TIP, and between the local transportation plans (if and when they exist) and the regional long-range planning documents (i.e., the MTP or the regional LRTP).

In addition to the local and regional guiding documents, there may be other relevant documents, such as corridor or project-specific studies (e.g., economic development and value capture studies, traffic and revenue analyses), and other funding and financial documentation that may inform the development of the CIP.

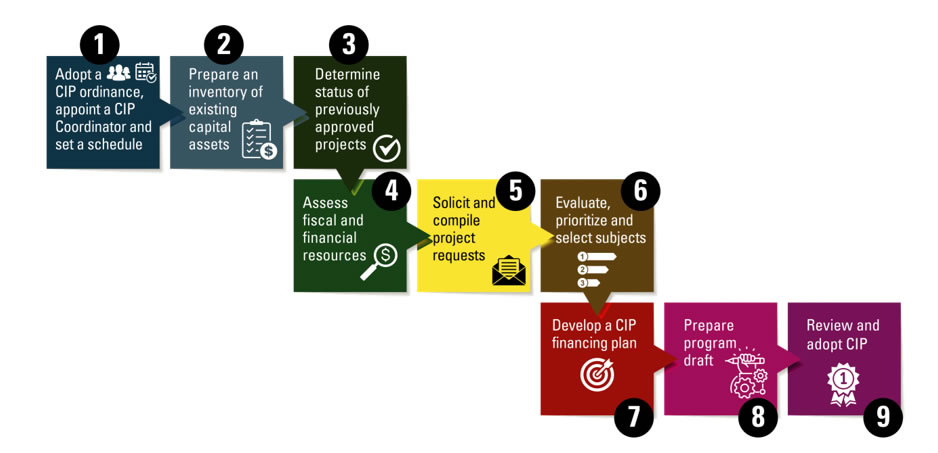

While the details vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction based on State and local laws, the process of developing of a CIP can be divided into nine sequential steps and is illustrated in Figure 2. Having a thorough understanding of the local government’s CIP internal and external stakeholders is crucial in each step of this process. It is crucial to understand stakeholders’ needs, priorities, and the resources they may be able to contribute toward the process.[xix] The steps in the process and their descriptions have been adapted from the Massachusetts Department of Revenue’s Capital Improvement Planning Guide9 and are described in the paragraphs that follow.

Figure 3. CIP Development Process [adapted from9]

When a CIP is adopted for the first time by a local government, the first step in the process typically includes creating the local legal framework for the adoption of the CIP and establishing roles and responsibilities for its development. This includes the local government governing body adopting an ordinance or bylaw requiring the adoption of a CIP and empowering a CIP coordinator to manage its development. In most cases, State law does not require local governments to adopt a CIP, so it is important for local governments to create a local framework for its adoption and continued use.

Once the legal framework has been adopted, a CIP coordinator is appointed. The CIP coordinator position is generally occupied by a local government official (e.g., mayor, council or village president, manager, administrator) or a staff member in the department of planning, public works, or finance. The CIP coordinator may be supported by a group of local government staff (or a consultant). The CIP coordinator often works with a CIP planning board or a CIP advisory committee that may consist of local officials, citizens, or key departmental staff.

Each year, the CIP coordinator establishes a schedule for all local officials with specific deadlines for completing each step of the CIP development process. Ideally, the schedule allows sufficient time to complete reviews and to present recommendations to the local government’s governing body.

Developing a comprehensive inventory of all local government property, assets, and fleet is of critical importance in developing a CIP. The inventory ideally includes all buildings, fleet, equipment, utilities, roads and streets, and sewers, and for each asset, the date when it was built, acquired, or last improved; the original cost; current condition; expected useful life; depreciated value; extent of use; and any scheduled replacement or expansion dates. This may be challenging for extensive road and street asset networks if an asset management system or pavement management system is not already in place and frequently updated. As a starting point, some information for completing this step may be found in the local government’s accounting and management systems. However, the CIP coordinator also might solicit detailed asset information from each department head for the most complete and up-to-date information. The head of the department developing the transportation component of the CIP might consider reaching out to its MPO or State DOT to inquire about asset management plans maintained by these agencies, which may have transportation asset information relevant to the local network that could assist in this task.

This step involves reviewing the capital projects that the local government already has underway to evaluate whether additional funds are needed and to determine the amount of unspent funds that may be available from completed or discontinued projects. This step also allows local officials involved in the budget process to stay informed of the progress of projects approved in prior years.

In this step, the local government’s finance office analyzes the local government’s fiscal condition by assessing recent trends and projections of revenues and expenditures, including debt and other liabilities. This analysis allows local government officials and its governing body to assess the implications for setting fiscal policies (e.g., setting tax rates and assessing debt capacity) and helps the CIP coordinator propose a CIP with a funding source schedule designed to meet the community’s fiscal policies and financial constraints.

Next, the CIP coordinator usually solicits capital improvement project requests from all local agencies and departments ranked in order of priority. In most cases, two different project request forms are used for each CIP capital improvement submission. The first one is the project cost summary form, which provides the costs to date for projects underway, costs for the next fiscal year, and estimated future costs for each capital improvement (see the example in Table 12 in the appendix). On the other hand, the project detail form provides comprehensive information on the capital improvement request. For more details about the contents provided by the project detail form, refer to Section 2.2.4 of this document, and to the examples in Figures 10 and 11 in the appendix. If the project is selected, the final version of these two forms will be included in the draft CIP. The project detail form and the project cost summary form will help ensure that all capital improvements identified are properly justified and characterized in terms of implementation schedule, cost, impact on the operating budget, and anticipated sources of funding.

In this step, the CIP coordinator convenes several meetings that typically include the local government’s managerial leadership (e.g., planning director, public works director, finance director, local government manager, mayor) to review, discuss, and critique the project proposals received. In communities that have a CIP planning board or CIP advisory committee, similar meetings and discussions may take place. It is critical to secure citizens’ participation at some point in this step. Generally, the CIP planning board is responsible for obtaining citizens’ participation in the CIP process through hearings. However, some local governments prefer to establish a citizens’ advisory panel to incorporate the public’s perspective. The objective of this step is to put together a draft CIP that is consistent with official plans and policies, contains projects that are supportive of the community’s development objectives, and can be submitted for the approval of the local government’s governing body. More specifically, proposed transportation projects are reviewed for consistency with comprehensive and transportation plans, technical feasibility, proposed costs and funding sources, schedules, and project readiness, and coordinated with other appropriate projects. At this juncture, the CIP coordinator (or the CIP planning board) may request clarification of certain aspects of a particular project from the agencies or departments that submitted it. Sometimes the CIP coordinator (or CIP planning board) may recommend excluding or postponing a project request and may communicate such recommendations to the agencies or local government departments involved, along with the reasons that supported the recommendation.

Next is the setting of priorities and ranking of project proposals, which is one of the most difficult but crucial tasks in the CIP development process. Generally, projects are prioritized using a scoring system based on established criteria to assess project readiness and the value that each project brings to the community. A CIP may have different scoring systems for different types of projects (e.g., one for roadway projects and another for sewer projects). Sometimes the CIP coordinator may convene a scenario-based workshop with the local government’s managerial leadership and the planning board to jointly analyze different priority project combinations and to select one that best meets community goals. These systems provide a uniform structure for evaluating capital improvements. Table 12 in the appendix shows an example of the scoring system used by Vanderburgh County (Indiana) for evaluating roadway infrastructure projects.12

However, scoring systems are not designed to replace professional or political judgment. Certain projects may rank low according to the scoring system, but they may still be included in the draft CIP as a result of a specific need or resource availability. For example, projects receiving a low score because they do not contribute to policy areas but are critically needed (such as replacing a very old bridge) can be elevated in the ranking based on needs and resources.

This step results in a list of projects selected to be included in the draft CIP in order of priority.

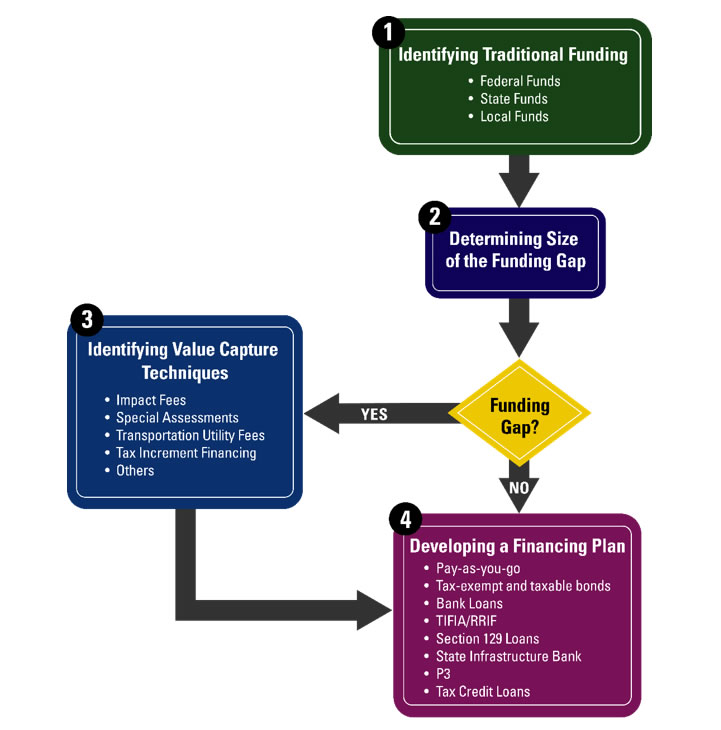

The objective of this step is to recommend a method to fund each project based on the policies and constraints identified in the assessment of fiscal and financial resources. There are numerous funding sources and financing mechanisms that may be used to pay for local capital projects. These were discussed in detail in Chapter 1, and include current revenue (e.g., general taxation, fees), debt instruments (e.g., general obligation and revenue bonds), State and Federal grants, and what is known as value capture techniques (e.g., tax increment financing, special districts and special assessments).

During this step, the feasibility of using different funding sources and financing mechanisms is evaluated for each project selected. In general, municipal debt is one of the most common sources for very costly capital projects. Bonds are issued for periods ranging from 5 to 30 years, over the course of which principal and interest are paid. Paying back debt over time has the advantage of allowing the amortization of the capital project over the life of the asset. For smaller capital projects, communities often use current revenue available in a given year. Finally, for certain projects, communities can seek capital funding from programs and grants offered by State and Federal governments. Transportation projects fall into this category. Local circumstances may impact the cost and potential funding sources for a project. For example, in locations where flood control is a significant issue, a local government’s transportation improvements may be more costly; however, if flood control infrastructure is managed by a separate local government unit with its own funding sources, both local government units have an opportunity to leverage one another’s funds on projects of mutual interest. Identifying all of these opportunities to leverage different funding sources is critical for CIP coordinators.

State and Federal transportation funds and grants have traditionally been a major funding source for the largest and most significant transportation improvements in communities across the country. However, three factors are increasing the adoption of innovative funding and financing techniques by State and local governments. The first is that Federal transportation funds can be used on only about a quarter of public roads, leaving more than 3 million miles of roads, especially local roads, without any access to Federal-aid highway funding.13 The second factor is that the growth in local transportation needs has outpaced the availability of traditional State and Federal funding sources.14 Finally, the third is that Federal funding and revenue targets that local governments, MPOs, and State DOTs rely on when preparing their CIPs, TIPs, and STIPs have become less predictable due to short-term Federal budget appropriations, extensions, and continuing resolutions.15 It is in this context that innovations such as the use of value capture techniques are increasingly playing a pivotal role in helping communities raise local transportation funds to reduce funding gaps and increase funding certainty for critically needed projects.

Figure 3 illustrates the typical process used to identify transportation funding sources and develop the financing plan for a CIP’s transportation component. The process starts with the identification of traditional transportation funding sources available for each capital improvement selected. This may involve discussing opportunities to leverage funds with other local agencies (e.g., a flood control district) for common priority projects. Next, the CIP coordinator compares the funding available from traditional sources with the funding needed by the proposed projects to estimate the funding gap. The CIP coordinator may then consider incorporating value capture techniques to help secure additional funding and narrow the gap as much as possible. Once traditional funding sources and value capture techniques are identified, the CIP coordinator reviews all financing mechanisms available and develops the financing plan. Developing a financing plan that effectively uses value capture benefits from the CIP coordinator having a realistic understanding of the timing when revenue from the value capture techniques is needed, and when the revenue can actually be accounted for in the CIP. Each technique will have different timing and process requirements before revenue becomes available (e.g., feasibility studies, hearings, approvals), which will impact when funding can be incorporated into the CIP financing plan.

Figure 4. Developing a CIP Financing Plan

The next step is usually the preparation of the draft CIP by the CIP coordinator. The draft CIP includes a prioritized list of projects with their schedule and cost estimates, funding sources, and detailed project information (e.g., project description and justification, photos, maps). The draft CIP consists of the four elements described in Section 2.2. These elements are (1) narrative, (2) prioritized list of projects and costs estimates, (3) funding and financing sources, and (4) project detail forms. The final draft CIP and the recommended capital budget is submitted to the governing body for its review and adoption. In communities that have a CIP planning board, they may have to review the draft CIP before recommending it for submission to the local governing body for adoption.

The last step in the CIP development process is the review and adoption of the draft CIP and capital budget by the local governing body. The governing body typically reviews all recommended projects included in the draft CIP and, in particular, the projects listed for the next fiscal year that should be accounted for when developing the annual budget. Projects and capital equipment purchases that are included for the first time in the CIP also need special attention. In addition, ongoing projects that incur delays and higher costs than that originally estimated should be expected to be reviewed in depth. Finally, the governing body will likely pay additional attention to projects that are moved forward several years within the CIP time horizon.

In this step, the public and representatives of public groups and organizations will likely have the opportunity to review the CIP projects at public hearings. Once the review has been completed, the governing body makes the pertinent revisions and changes to the draft CIP and the capital improvement budget. Finally, the resulting CIP and capital budget are adopted.

The process of administering a CIP can be divided into two major steps—executing the approved CIP and updating the CIP.

Once the governing body adopts the capital budget and the fiscal year begins, local government departments are authorized to commence implementation of the projects. However, they will need to coordinate the purchasing of equipment or services in advance with the department of finance or budget to confirm that the funds are available at that time.

The execution of transportation capital improvements involves a set of actions that can be grouped into the following categories: planning and community engagement, environmental, right-of-way, design, and construction. Each of these actions has an inherent level of uncertainty. In the case of major transportation infrastructure projects, planning and community engagement actions may require more than 1 year. Dealing with utilities and right-of-way coordination may be challenging and time consuming, particularly when dealing with various entities (e.g., power and telecommunications). Certain capital projects are also required to complete a set of environmental processes before construction begins. In addition, the need for acquiring land for right-of-way adds more complexity and uncertainty to the execution of capital improvement projects. Finally, the actions under the design and construction categories warrant close monitoring to detect any design errors and construction problems that would impact the capital improvement budget and schedule.

The CIP is a powerful tool for coordinating all of these actions and it helps ensure that the capital improvement is executed on schedule and within the budget. If the CIP is the only tool used to monitor the execution of the capital improvements, it is critical to review it annually. There are other procedures for monitoring the execution of capital improvements, depending on State laws, the local CIP ordinance, or other local ordinances. For example, local governments may require the department, agency, or organization authorized to execute the capital improvement to submit reports on a regular basis to the administrative body in charge of monitoring the execution.9 By monitoring the execution of capital projects, local governments are able to identify such issues as major problems (e.g., structural failure, accident) and changes in the schedule and costs.

It is important to update the CIP periodically. Most communities do it every year, while others do it on a biennial basis. Updating the CIP involves repeating steps 2 through 9 of the CIP development process, shown in Figure 2, to reflect new information, policies, and proposed projects. The CIP coordinator typically reviews the entire program, as necessary, to ensure that changes in community needs and fiscal policies are accounted for, and that new uncommitted funding sources are allocated. The periodic review and update of the CIP will also ensure that cost and funding amounts for the current and future years are also updated.

Certain local governments may review the CIP only when major capital improvements are needed. However, this practice significantly reduces the usefulness of the CIP as a fiscal planning tool and reduces the chances of accessing certain funding sources and grants that require time and planning to be secured. Moreover, this practice limits the capabilities of the CIP as a tool to monitor ongoing projects in terms of schedule, costs, and financial status.

In terms of the timing of preparation, local governments may find it desirable to prepare the CIP and the annual budget at the same time. However, the preparation of the CIP and the annual budget require significant work and sometimes it is not possible to perform both processes at the same time. In these instances, local governments may prefer to complete the annual budget process before developing or updating the CIP. The paragraphs that follow discuss the relationships between the CIP and the annual budget in terms of timing and content.

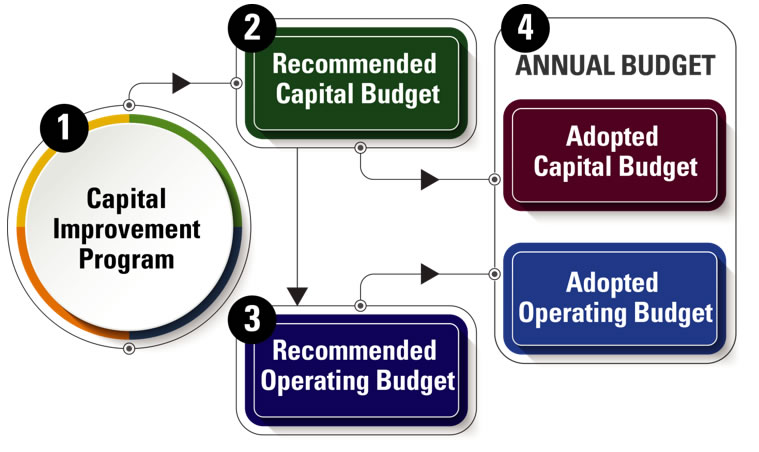

A capital cost is defined as each individual outlay of a capital expenditure. For example, for the construction of a bridge, the cost of designing it or of acquiring the land where the bridge will be located are capital costs. Capital costs during the first year of the CIP become the recommended capital budget. However, the recommended capital budget is not legally binding. It only provides recommendations for developing the adopted capital budget (see Figure 4).

Figure 5. Annual Budget Structure

Some of the capital costs contemplated in the recommended capital budget are transferred to the recommended operating budget, as indicated by the arrows in Figure 4. This is the case of capital expenditures that are funded using financing mechanisms that involve debt. The debt service then becomes an operating expenditure that should be included in the recommended operating budget. Adopted capital and operating budgets are the two main elements of the annual budget.

In addition to debt service, capital expenditures may affect the operating budget in terms of maintenance costs and cost of personal services. In other words, certain capital improvements can increase or decrease operating expenditures. For instance, the replacement of an old bridge that requires frequent maintenance work for a new one would decrease operating expenses for future years. On the other hand, the construction of a new corridor to serve a new development will be translated into new operating expenditures. Therefore, it is highly beneficial to evaluate the operating expenditures associated to each capital improvement during the CIP process.

[xv] Depending on the jurisdiction, comprehensive plans are also known as master plans, general plans, and more recently, strategic plans.6

[xvi] Regional or metropolitan level guiding documents are governed by 23 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Part 450, Planning Assistance and Standards.

[xvii] For local governments in areas with a population of less than 50,000, the applicable long-range transportation planning guiding document is the statewide long-range transportation plan.

[xviii] According to Federal transportation planning and programming regulations (23 CFR Part 450), a transportation plan or program demonstrates constraint by “including sufficient financial information to confirm that projects in those documents can be implemented using committed or available revenue sources, with reasonable assurance that the federally supported transportation system is being adequately operated and maintained.”

[xix] Internal stakeholders include, but may not be limited to, the local government’s constituents and governing body, its different department heads, and the staff in each of these departments. From the transportation component standpoint, the community’s external stakeholders would include, among others, Federal agencies (e.g., Federal Highway Administration, Federal Transit Administration, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency), State agencies (State DOT and State environmental agencies), and regional planning bodies (e.g., the MPO).