TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF FIGURES

LIST OF TABLES

This chapter illustrates how communities of different sizes have used value capture techniques to fund different transportation projects included in their CIPs. Moreover, this section presents how these communities used the CIP as a fiscal planning tool to execute the projects on time and within budget.

Table 8 identifies the four case studies (i.e., projects) included in this chapter and provides the following information fields: community name and the State where it is located, community size, project name, and value capture techniques used to fund the project. In this document, it is assumed that a large community has a population of more than 500,000, a medium community has a population between 100,000 and 499,999, and a small community has a population of fewer than 100,000.

Community Name and Location |

Community Size |

Project Name |

Value Capture Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

City of Phoenix, AR |

Large |

Baseline and Loop 202 Intersection |

Impact Fees |

Fairfax County, VA |

Large |

Special Assessments: Dulles Corridor Metrorail Project |

Special |

City of Hillsboro, OR |

Medium |

Jackson School Road Project |

Transportation |

Town of Horizon, TX |

Small |

Eastlake Boulevard Extension Phase 2 |

Tax Increment Financing |

The following sections provide relevant information on each project. Specifically, each section provides some background information on the project and how the project was funded or financed. Moreover, this section discusses the lessons learned by each community.

The Baseline and Loop 202 Intersection Project is an example of how the City of Phoenix, a large size community, uses the impact fees as a complementary funding source to deliver critical projects that satisfy the transportation needs of new developments. The City of Phoenix uses the CIP to ensure that funds from complex funding packages are available when they are needed.

The City of Phoenix, Arizona, had an estimated population of 1.6 million in 2019. The CIP plays a pivotal role in the capital improvement planning process of the City of Phoenix. On one hand, the CIP is used as a tool to implement the Phoenix comprehensive plan, along with the transportation plans. On the other hand, Phoenix uses the CIP as a fiscal planning tool to keep its budget balanced as mandated by the State of Arizona.17

The City of Phoenix established the impact fee program in the 1980s for the areas with the fastest growth. At that time, these areas located in northern and southern parts of the city were entirely or mostly undeveloped. Impact fees are charged under the police power (similar to land use controls and associated infrastructure standards). Impact fees must comply with extensive common law precedents or court cases and a State statute, so credit must be provided for developer facility dedications or contributions, and offsets must be provided for future homeowner or business contributions to growth-related infrastructure (via water rates, sales taxes, property taxes, etc.).18 As the State of Arizona mandates, impact fees must be used to fund projects that serve new developments. The law prohibits the use of funds generated by impact fees to repay debt. The law also prohibits impact fee revenues from being spent on operations, maintenance, repair, rehabilitation, environmental, or other non-capital expenditures.

Originally, impact fees areas were mostly consistent with urban village boundaries (the City of Phoenix has 15 urban villages). Each urban village had its own adoption process, projections of development (e.g., by type, density), inventory of needed facilities (e.g., location, attributes, cost), and impact fee rate (by equivalent dwelling unit). Over time, the City of Phoenix consolidated areas (where defensible), streamlined processes, and changed various aspects of the program to reduce the administrative burdens on the development community and meet increasing State of Arizona requirements.

Currently, the City of Phoenix collects impact fees for the following categories: streets, drainage (in specific areas), water, wastewater, water resources, police, fire, parks, and libraries. Only large facilities, such as major arterial streets, water transmission mains (16†and larger), 100-year event regional flood control channels or basins, and neighborhood parks, are eligible to be funded with impact fees.18, 19

According to the City of Phoenix, the impact fee program, overall, has been a notable success, providing more than $34 million in revenues in fiscal year 2019–20.18 Numerous transportation, potable water, wastewater, and drainage or flood control projects have been constructed using cooperative arrangements between the City of Phoenix and developers, the Flood Control District of Maricopa County (FCDMC), and/or the Arizona State Land Department (ASLD). Existing impact fee balances or future impact fee revenues have been combined with developer contributions, FCDMC funding, and ASLD participation to initiate key infrastructure projects that have facilitated development in the growth areas over the past 30 years.

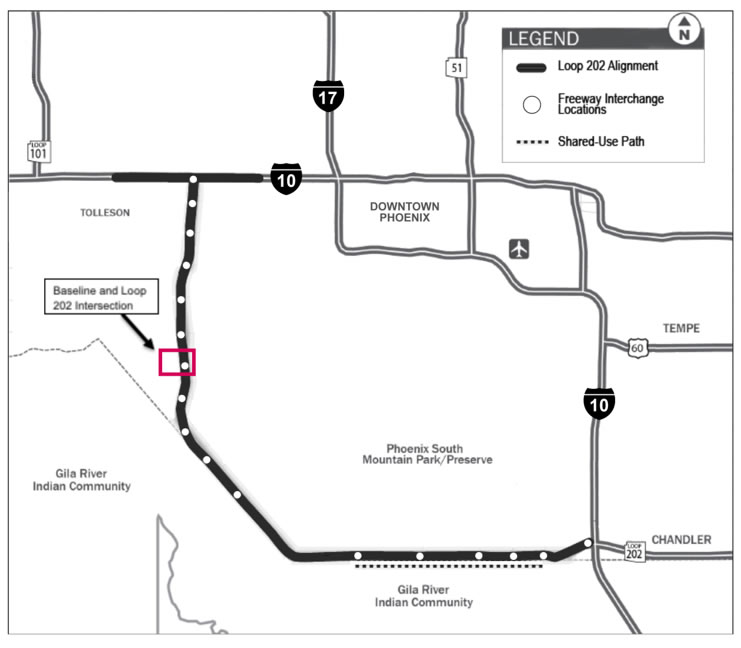

One of the last major highway projects in the City of Phoenix proper is the South Mountain Freeway (Loop 202). It connects the western part of the valley with the eastern part of the valley via a six-lane project that links Interstate 10 on the west side of downtown Phoenix to Interstate 10 southwest of downtown (see Figure 5). Loop 202 was recently completed after many decades of planning, public debate, legal action, and then funding issues, providing additional transportation access to three Phoenix village planning areas—Estrella, Laveen, and Ahwatukee.20

Figure 6. Loop 202 (South Mountain Freeway) (Source: Arizona DOT)

Loop 202 connects with a number of major arterial streets in Phoenix, and one of those is Baseline Road, which is an important east-west artery that serves much of the Laveen area. The area in the vicinity of the Baseline and Loop 202 intersection (see red square in Figure 5) is a mix of recently developed single-family residential land and vacant land that will be used for residential and commercial development. On the east side of the intersection, a new arterial road and associated improvements were required, and the frontage of this road is held by numerous landowners who plan to construct commercial developments.

Some of the landowners plan to initiate improvements soon while others do not; one landowner wanted to begin development immediately, precipitating the need for arrangements on the design and construction of the roadway on both sides of Loop 202. This negotiated transaction was intended to be a public and private agreement to expedite and get economies of scale for the design and construction of the roadway connection to the new Loop 202, which was under construction.20

In the Baseline and Loop 202 Intersection Project, the City of Phoenix and landowners agreed to perform design and construction of the project at one time to accommodate the anticipated development on all four commercially zoned corners, avoiding ongoing road construction and associated congestion while reducing costs. To facilitate this type of arrangement, the City of Phoenix decided to assist with the coordination of the project and contribute financially to it using street impact fee funds.20

Specifically, the City of Phoenix agreed to pay for the curb-to-curb construction costs of the project if the adjacent landowners pay for all remaining costs, including those associated with sidewalks, parking lot and collector access, streetlights, signage, and adjacent improvements (including landscaping). The City of Phoenix used existing funds in the Southwest (Laveen/Estrella) street impact fee account for this purpose. The total cost of the project was approximately $3.3 million, and the city contributed approximately $1.6 million from street impact fees. In addition, the adjacent landowners provided the required public right-of-way to be dedicated for the roadway improvements.

Overall project costs were reduced because of this coordination between the City of Phoenix and landowners. In addition, construction timelines were reduced, helping to limit congestion and access problems. As a result, the City of Phoenix was able to achieve many of its transportation and economic development objectives without having to take on the responsibility of designing and constructing a major arterial intersection itself. The role of the City of Phoenix was limited to coordination and providing a financial contribution that was capped at $2 million.

The Baseline and Loop 202 Intersection Project is funded by impact fees along with other funding sources. The use of impact fees brings opportunities and generates some challenges.

Impact fees bring the opportunity of having a new funding source, collected upfront, for transportation projects. The implementation of impact fees creates little public resistance, even though they are sometimes seen as a new tax. Finally, impact fees encourage developers to start the projects as soon as they are ready, thus expediting the pace of development. This is because all developers must pay impact fees regardless of the implementation status of the new transportation improvement. The practice of delaying developments, waiting for transportation improvements to be completed, and avoiding contributing to those is observed in other parts of the City of Phoenix where impact fees are not in place.20

The City of Phoenix faces different challenges associated with its impact fees. In order to implement the transportation impact fees, the City of Phoenix had to spend a significant amount of resources and coordinate across city departments to fulfill the obligations mandated by the State of Arizona. Once the impact fee was implemented, the City of Phoenix faced other challenges that can be grouped into revenue stream challenges and administrative challenges.

Revenue streams generated by impact fees are mainly driven by the pace of development and the size of the development. Small developments of less than 1,000 square feet provide small revenues. Moreover, new developments occurring in areas with several landowners generally develop slowly, and therefore, impact fee revenue generation is also slow. The fact that revenues are so cyclical and could potentially be reduced or eliminated because of new statutory restrictions makes it difficult to use impact fees as collateral for issuing bonds. In practice, an entity with real property taxing power, such as the City of Phoenix or a Community Facility District, uses future real property tax revenues as collateral to secure low-interest rate financing. Then, impact fee revenues are used to pay the debt. In some instances, developers funded the projects and the City of Phoenix repaid them using revenues generated by impact fees. Every year, as part of the CIP development process, the City of Phoenix performs forecasts on impact fee revenue potential for the next 5 years. This practice allows the city to closely monitor impact fee annual revenues and describe the uncertainty associated with them. Another challenge is that impact fees are not sufficient to fund the entire transportation project. They just complement traditional funding sources, helping to close the funding gap.20

Regarding administrative challenges, the State of Arizona requires the development of 10-year horizon impact fee plans, annual impact fee reports, and a biennial audit of the impact fee reports. This is translated into a significant amount of resources spent every year to administer the impact fees. Another administrative challenge is associated with the lack of flexibility of funds generated by impact fees. These funds must be exclusively used to fund projects that meet the transportation demand of new developments. Finally, the City of Phoenix encounters resistance from developers and landowners who complain about the fees. One of the main complaints is that impact fees charged to new developments located north of the city are the highest in the entire city. The reason why this occurs is because transportation project costs are higher in that area due to drainage issues that should be addressed during project construction. To decrease developers’ and landowners’ resistance, the City of Phoenix created the Committee of Development. This committee obtains inputs from developers and landowners, and provides them with all available information about impact fees. As a result, the City of Phoenix increases transparency and accounts for inputs from developers and landowners, thus ensuring fair and equitable impact fees.20

The Dulles Corridor Metrorail Project illustrates how Fairfax County, a large and heavily urbanized community, uses revenues generated by two Transportation Improvement Districts (TIDs), a type of special assessment, to partially fund a transit project listed on its CIP. Fairfax County uses the CIP as a planning tool to coordinate the financing and timing of the Dulles Corridor Metrorail Project in a way that maximizes the return to the public.

Fairfax County, located in the Commonwealth of Virginia, had an estimated population of 1.14 million in 2019. The comprehensive capital project planning process of Fairfax County has three essential components. These are the comprehensive plan, the CIP, and the capital budget. The comprehensive plan communicates policy directions for the next 20 to 25 years. The CIP identifies the capital improvements to support the implementation of the policies of the comprehensive plan. Finally, the capital budget serves as a tool to appropriate the funds for the capital improvements identified by the CIP.21

The Commonwealth of Virginia provides a legal framework authorizing local communities with taxing power, such as towns, cities, or counties, to establish TIDs. Under the current legislation, local communities can tax commercial and industrial properties located in the TID to fund transportation improvements within the district. Local communities can establish a TID if at least 51 percent of commercial and industrial real property owners (measured in area or real property assessed value) must make a formal petition.[xxi] Residential properties are not taxed by the TID. However, multifamily rental properties are considered commercial properties and taxed by the TID.

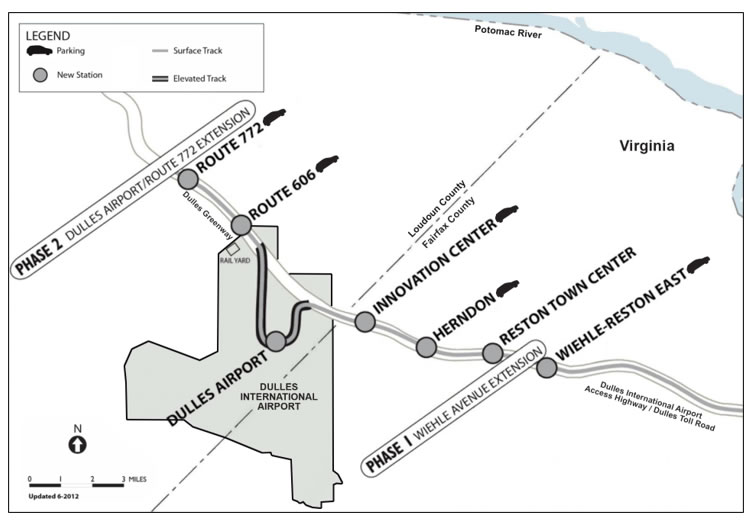

The Dulles Corridor Metrorail Project is a 23-mile extension of the Washington, DC, area metro from the East and West Falls Church stations located along I–66, extending along the Dulles Connector Road to Route 123, then through Tyson’s Corner to Route 7, turning west to reconnect with the Dulles International Airport Access Highway, and then to Dulles Airport and into Loudoun County (see Figure 6). The project was designed to be executed in two phases. Phase 1 of the project runs 11.7 miles from East Falls Church to Wiehle Avenue in Reston, Virginia (see Figure 6). Phase 2 will continue 11.4 miles from Wiehle Avenue to eastern Loudoun County, Virginia, as shown in Figure 6. Phase 2 will add six stations, including stops in Reston, Herndon, Dulles Airport, and Ashburn.22

Figure 7. Silver Line Project23

The construction of Phase 1 of the Dulles Corridor Metrorail Project began in March 2009. Phase 1 opened to the public on July 26, 2014. The total cost of Phase 1 was approximately $2.9 billion. This phase was funded with a mix of Federal, Commonwealth, and local funding sources. Local funds were provided by Fairfax County, Loudoun County, and the Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority. Fairfax County agreed to pay $400 million for Phase 1 construction costs. In 2013, the county completed its $400 million payment using a combination of funds generated by the Phase 1 TID and bonds secured by future revenues of the TID. Total tax revenue collected since the TID was established in June 2004 was approximately $364.1 million (as of February 2020). The Phase 1 TID allows a tax rate of up to $0.40 per $100 of assessed real property value. The tax rate for the Phase 1 TID in 2020 was $0.11 cents per $100 of assessed value of commercial or industrial real properties. This tax rate will remain in effect until all debt service payments have been paid in full.21

On the other hand, the construction of Phase 2 began in 2014 and it is expected to start operations in early 2022.24 25 The Phase 2 estimated cost is $2.8 billion. Fairfax County agreed to pay a total of $575 million for the construction of Phase 2. For Phase 2, a total of $330 million will be funded by a second TID established around the Phase 2 metrorail corridor within Fairfax County. Total tax revenue collected since the TID was established in December 2011 is approximately $120.7 million. The initial tax rate of the special assessment was $0.05 per $100 of the taxable value of commercial or industrial real properties in 2011, with annual increases of $0.05 up to a maximum of $0.20 that was reached in 2014 and was kept constant through 2020. When full revenue operations commence on Phase 2 in April 2021, the tax rate may be increased to fulfill debt obligations.21

Fairfax County used funds generated by two TIDs to partially fund Phase 1 and Phase 2 of the Dulles Corridor Metrorail Project. This section discusses opportunities and challenges faced by Fairfax County during the implementation and administration of the TIDs.

The TIDs generate consistent revenue streams that can be used as funding or financing mechanisms. Particularly, revenues generated can be deposited into the TID account and be used on a pay-as-you-go basis. Nonetheless, future revenues generated by the TID can be used to issue bonds and secure the funds upfront or during appropriate project phases to pay for the project. In this regard, Fairfax County has been using funds generated by the two TIDs on a pay-as-you-go basis and to issue bonds. In other words, TIDs have been used as funding and financing mechanisms to deliver the Dulles Corridor Metrorail Project.21 In addition, funds generated by TIDs offer a certain flexibility in terms of the type of project for which they can be used. Specifically, TID revenues can be used to fund transportation projects within the district that are identified in an adopted land use development plan.

In general, the implementation of TIDs may face resistance from landowners and developers because it is a new tax. Moreover, real property owners within the district may argue that their neighbors outside the district or future residents are not asked to pay the fee although they are benefiting from the improvements. This can be translated into a lack of support. According to the Commonwealth of Virginia, to initiate the process of establishing a TID, at least 51 percent of the commercial and industrial real property owners (measured in area or real property assessed value) must make a formal petition. In Phase 1 of the Dulles Corridor Metrorail Project, this challenge was overcome with the help of a group of developers who supported the idea of contributing to fund the project by means of a TID. The group was named Landowners Economic Alliance for the Dulles Extension of Rail (LEADER). This group carried out an outreach campaign to gather the support required to formulate the TID petition of Fairfax County.26

Once the TIDs are established, Fairfax County faces other challenges that can be grouped into revenue stream challenges and administrative challenges. Revenues generated within the TIDs are mainly driven by new development and growth in real property assessed values. These two main drivers are uncertain, and this uncertainty is transferred to future revenues generated by the TIDs. Every year, as part of the CIP development process, Fairfax County performs forecasts on TID revenue potential for the next 10 years.21 Moreover, the District Commission performs a revenue computation for the current year (budgeted) and a forecast for the following year.27 28

Fairfax County faces two main administrative challenges. These are perceived lack of transparency and equity. Regarding transparency, some landowners and citizens may see TIDs as a hidden local government within the county. To address this challenge, the Board of Supervisors meetings with the Phase 1 and Phase 2 Dulles Rail Transportation Improvement District Commissions are streamed live and can also be viewed on demand via the Fairfax County website. On this website, meeting materials since the TIDs were established are available to the public. Finally, the TIDs may raise equity concerns. Specifically, some property owners in the district may argue that tax rates are high. In this regard, the District Commissions of Phase 1 and Phase 2 TIDs evaluate the capacity of meeting the annual debt commitments of the TIDs adopting different tax rates and recommend a tax rate for the next fiscal year. The results and recommendations of these analyses are presented every year to the Board of Supervisors, landowners, and the public.29 30

The Jackson School Road Project is a clear example of how a medium size community uses the CIP as a fiscal planning tool to prepare a diverse funding package that addresses a roadway maintenance backlog. The use of the CIP ensures the adequate combination of funds from various sources in time and quantity over the entire life of the project. As a result, the funds are available when they are required, expediting the delivery of the project. The City of Hillsboro funded the Jackson School Road Project using TUFs, impact fees, and other traditional funding sources.

The City of Hillsboro, located in Washington County, is the fifth largest city in the State of Oregon. In 2019, the city had an estimated population of 109,128 residents. The Hillsboro City Council has adopted the Hillsboro 2035 Community Plan. The plan shares the vision and expresses the desire of the community for a safe, environmentally sustainable, and accessible transportation system with enhanced transit, pedestrian, and bicycle facilities.31 The City of Hillsboro uses the CIP to implement its community plan. In this regard, the City of Hillsboro CIP includes a list of transportation capital improvements that requires the investment of millions of dollars to be funded from various sources, including value capture techniques.

Transportation capital improvements are funded by means of Federal, State, and local sources. Historically, communities in the State of Oregon had relied on gas taxes, vehicle registration fees, and large truck weight-mile fees to pay for transportation improvements. In fact, Oregon was the first State to adopt a gas tax in 1918. Currently, the State of Oregon fuel taxes are $0.36 per gallon. Moreover, Washington County imposes an additional $0.01 per gallon local gas tax. As of today, the City of Hillsboro does not have a local gas tax in place. State and county gas taxes are not sufficient to pay for improving and maintaining the streets of the City of Hillsboro. In 2006, the city started exploring new funding sources to help close its funding gap.32 These efforts resulted in the adoption of a TUF that the City of Hillsboro approved in 2008 and went into effect in March 2009. The TUF was aimed at closing a funding gap in the street maintenance budget. The TUF is collected from all residential, business, government agency, school, and nonprofit properties in the city through the utility bill. Funds generated are used to improve pavement conditions throughout Hillsboro. In fiscal year 2020–21, the TUF is estimated to generate $3.8 million for the Pavement Management Program (TUF–Pavement Management) and $1.2 million for the Bicycle and Pedestrian Capital Improvement Program (TUF–Pathways).33

Using a combination of traditional funding sources and value capture funding, the City of Hillsboro is in the process of delivering the Jackson School Road Project. Northeast Jackson School Road between Northeast Grant Street and Northwest Evergreen Road is a collector street serving as a north-south link between downtown Hillsboro and Highway 26. It also serves as access to Jackson, Lincoln, and Mooberry elementary schools, and Hamby Park. Jackson School Road is currently a two-lane roadway with intermittent center turn lanes and incomplete sidewalks. It lacks safe bicycle lanes and has limited roadway lighting.34 Improvements include the following:

Project construction started in March 2020 and is expected to be completed in 2025. The estimated cost was approximately $29 million. The Jackson School Road Project was funded with a mix of traditional and value capture funding sources. The value capture mechanisms used to fund the project were impact fees and TUFs.35

The Traffic Development Tax (TDT) is an impact fee managed by Washington County. It became effective on July 1, 2009. The TDT is a one-time charge to developers based on the estimated traffic generated by a new development within Washington County. Funds generated by the TDT are dedicated to fund road and transit capital improvements that provide additional capacity to the transportation system of Washington County.36

The Traffic Impact Fee, managed by Washington County, was replaced by the TDT in 2010. However, remaining revenues are used to fund transportation projects. Revenues from the Traffic Impact Fee were used to fund transit capital improvements (Traffic Utility Fees for Transit) and streets or pathways capital improvements (Traffic Utility Fees for Collectors).37

Before the TUF was established in 2009, the City of Hillsboro relied solely on gas tax revenues to fund street maintenance. However, this revenue source was not sufficient to pay for ongoing maintenance needs, creating a significant maintenance backlog. Revenues generated by the TUF allowed the city to eliminate the maintenance backlog and maintain its streets in an adequate condition and meet its target level of service. The City of Hillsboro TUF consists of TUF–Pathways and TUF–Pavement Management. TUF–Pathways is the portion of the revenues generated by the City of Hillsboro TUF dedicated to sidewalk and bicycle path maintenance and improvements. TIF–Pavement Management is the portion of the City of Hillsboro TUF dedicated to street pavement maintenance.37

Table 8 presents the value capture mechanisms used to fund the Jackson School Road Project.37–41 Specifically, Table 8 shows the amount that each value capture mechanism contributes to the project in comparison with traditional funding sources. As can be observed, the value capture funding sources provide almost $18 million and traditional sources around $11 million. In other words, approximately 64 percent of the Jackson School Road Project is being funded using value capture techniques (see Table 8).

Project Costs |

Prior Years |

2020-21 |

2021-26 Estimate |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Pre-Construction |

$5,093,675 |

$350,000 |

$590,000 |

$6,033,675 |

Construction |

$4,042,000 |

$5,900,000 |

$10,073,367 |

$20,015,367 |

Other |

$1,805,747 |

$350,000 |

$0 |

$2,155,747 |

Total |

$10,941,422 |

$6,600,000 |

$10,663,367 |

$28,204,789 |

Funding Sources |

||||

TUF–Pavement Management |

$462,802 |

$396,000 |

$387,000 |

$1,245,802 |

TUF–Pathways |

$831,945 |

$726,000 |

$709,500 |

$2,267,445 |

Traffic Impact Fee – Transit |

$803,614 |

$462,000 |

$451,500 |

$1,717,114 |

Traffic Impact Fee – Collector |

$61,132 |

$61,132 |

||

Traffic Development Tax |

$5,984,964 |

$1,592,000 |

$3,999,000 |

$11,575,964 |

Traditional Funding Sources |

$2,796,965 |

$3,424,000 |

$5,116,367 |

$11,337,332 |

Total |

$10,941,422 |

$6,600,000 |

$10,663,367 |

$28,204,789 |

Source: Information extracted from38 39 40 37 41

The City of Hillsboro used funds generated by its TUF to deliver the Jackson School Road Project. This section discusses opportunities and challenges faced by the City of Hillsboro during the implementation and administration of its TUF.

The City of Hillsboro TUF brings the opportunity of adding additional funds to the street department budget to meet road maintenance needs. In 2020, revenues generated by the TUF represent approximately 60 percent of the City of Hillsboro’s street maintenance budget.42

The most frequent challenges faced by communities that want to establish a TUF are legal, political and public resistance, and administrative. Legal challenges sometimes arise from the lack of legislation enabling communities to create TUFs. In the case of the City of Hillsboro, the State of Oregon does not specifically define the principles that communities must follow to establish TUFs. Therefore, the City of Hillsboro had to reach community consensus before establishing the TUF.43 In 2007, the City of Hillsboro started the feasibility analysis of the implementation of the TUF. Consensus was reached in 2008. Finally, the TUF went into effect in March 2009. Political and public resistance may arise for two reasons. First, the public may feel that the form in which TUF rates are calculated is inequitable. This public resistance is frequently translated into political resistance, particularly during election years.44 Second, some entities, such as school districts and nonprofit organizations, may feel that they should be exempt from this fee. Once the TUF is established, administrative challenges related to equity and fairness at the time the TUF rate needs to be revised may occur. Another administrative challenge is associated with proper use of the revenues to exclusively fund maintenance projects and the need for project coordination with other utilities often buried in the street right-of-way (e.g., electricity, water, internet).

The City of Hillsboro Council appointed an Ad Hoc Transportation Finance Advisory Committee to address these challenges. The committee consisted of members representing the interests of all parties involved, making it possible to reach a consensus about all aspects related to the TUF. The committee members were:32

During nine 2-hour sessions, the committee discussed all aspects of the TUF. Based on the inputs from city staff and the consultant regarding the feasibility of implementing a TUF and the expected revenue, the Ad Hoc Transportation Finance Advisory Committee recommended the adoption of a citywide TUF to pay for the operations and maintenance costs of the city’s street network. The committee also recommended a TUF rate structure focused on equity and fairness. This structure considers waivers, credits, and incentives to account for different customers’ behaviors and circumstances. Moreover, the committee recommended the creation of a public education and outreach program to help the public better understand the need for establishing a TUF and the benefits associated with it. In this regard, the City of Hillsboro has a website with all information about its TUF, including ordinances. Moreover, the City of Hillsboro uses social media and advertisement campaigns to inform the public about the TUF. These initiatives have the objective of reducing public resistance and, consequently, political resistance. Regarding administrative challenges, the committee proposed the appointment of an oversight committee to ensure a fair and equitable system for rate revisions and the mandate of reducing or eliminating the TUF if sufficient revenue from State, Federal, or regional sources becomes available for street maintenance.32 Finally, the City of Hillsboro coordinates its maintenance plans with city departments or the private companies responsible for utilities buried in the street right-of-way every 1 or 2 years to reduce traffic disruptions and avoid duplicative efforts.42 The City of Hillsboro collects TUF revenues through the utility bill.

The Eastlake Boulevard Extension Phase 2 Project provides an example of how a small community facing rapid growth challenges was able to effectively collaborate with other local governments to improve regional mobility and tap into value capture as an innovative transportation funding tool to deliver a critical transportation project. The project also illustrates how beneficial capital improvement programming is in advancing projects that require complex intergovernmental cooperation and funding arrangements.

Having a CIP and incorporating value capture into project funding through a Transportation Reinvestment Zone (TRZ) enabled the Town of Horizon City not only to ensure that project funds would be available when needed, but also to develop interagency partnerships and leverage other financing mechanisms. The Eastlake Boulevard Extension Phase 2 Project was jointly funded by the Town of Horizon City using municipal TRZ revenues, and the County of El Paso, which used vehicle registration fee revenues. The Town of Horizon City and the County of El Paso partnered with a regional agency—the Camino Real Regional Mobility Authority (CRRMA), which in turn issued bonds backed by the county’s vehicle registration fees to pay for the project. The paragraphs that follow describe the project in more detail and summarize lessons learned that could be of interest to other local governments facing similar situations or challenges.

The Town of Horizon City is located approximately 20 miles southeast of the City of El Paso, in El Paso County, Texas. The town has grown very rapidly over the last two decades, going from 5,233 in 2000, to 16,735 in 2010, and reaching a population of 19,741 by 2018 (according to the U.S. Census estimate). Horizon City’s general fund revenue budget for 2020 was approximately $10 million, and its largest revenue source is property taxes. The town covers about 8.7 square miles and is mostly landlocked, abutting the City of El Paso, the City of El Paso Extra-Territorial Jurisdiction (ETJ), and the City of Socorro (Texas) ETJ.

In the face of these geographical and financial constraints, Horizon City has turned to strategic planning and management, and has been forced to consider innovative funding to meet its transportation infrastructure and mobility needs. Horizon City developed and adopted its first comprehensive plan—Vision 2020—in 2011. The Vison 2020 Plan also included the town’s first Major Thoroughfare System Plan. In 2020, a new comprehensive and strategic plan was adopted—Shaping Our Horizon: 2030—along with amendments to the Major Thoroughfare System Plan. In 2014, the town adopted its first CIP, which included $15 million for infrastructure projects, and issued certificates of obligation to fund local projects. Since then, Horizon City has continued to invest in infrastructure, with a combination of local and Federal funds and a 2018 CIP debt issuance totaling $13 million to fund park projects.45 The town’s most recent CIP totals $117.7 million of funded and unfunded projects.

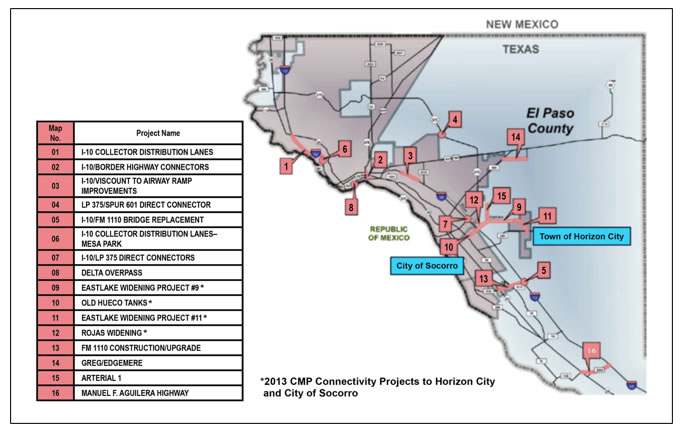

In 2013, Texas DOT, El Paso County, CRRMA, the Town of Horizon City, and the City of Socorro partnered to develop the El Paso County Comprehensive Mobility Plan (CMP). The plan, endorsed by the El Paso MPO, presented a long-term mobility vision for the El Paso region and outlined objectives, strategies, and policy measures to achieve this vision.46 The 2013 CMP consisted of a set of 16 multimodal projects, including pedestrian facilities, spread throughout El Paso County (see Figure 7). The plan included accelerating projects outside the boundaries of the City of El Paso to meet the connectivity and growth requirements of the Town of Horizon City and its neighbor to the south of I–10, the City of Socorro, Texas (see projects 9, 10, 11, and 12 in Figure 7). The total estimated cost of the 2013 CMP was $406 million, and the funding package included $260 million in Federal and State funds, $132 million in county vehicle registration fee (VRF) funds, $9 million from the City of Socorro, and $5 million from the Town of Horizon City.46

Eastlake Boulevard Extension Phase 2 (referred to as Eastlake Widening Project #11 in Figure 7) was the CMP project to which Horizon City dedicated its contribution. The project was critical for the town as it significantly improved the town’s access to I–10 and connectivity to the City of El Paso, as well as to its neighboring City of Socorro. The project consisted of reconstructing and widening the existing Eastlake Boulevard from Darrington Road to Horizon Boulevard from four to six lanes, and initial estimates were approximately $19 million.46

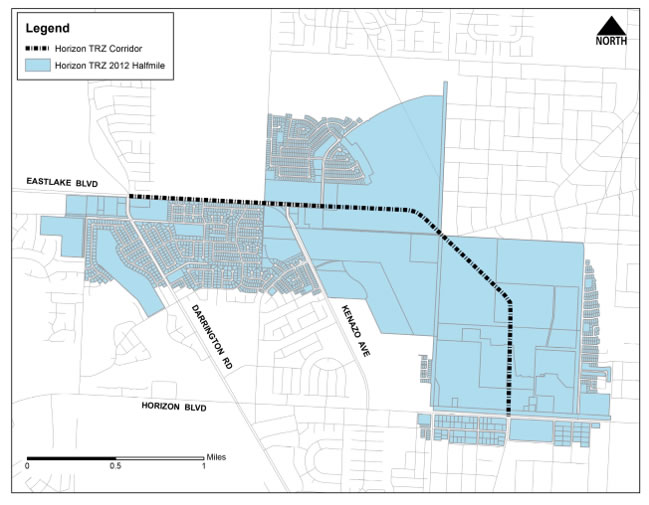

Figure 8. 2013 El Paso County Comprehensive Mobility Plan46

After reviewing different options to generate its local match contribution to the CMP funding package, the Town of Horizon City decided to try a relatively new transportation funding tool for Texas local governments—a transportation reinvestment zone. TRZs are a tax increment financing mechanism that relies on real estate property tax increments within the zone to generate funding for transportation infrastructure. The Horizon City Town Council approved creation of TRZ No. 1 in November 2012. The zone designated the TRZ to include all parcels within a buffer of approximately a half-mile on either side of the roadway, which included 2,104 parcels and a total extension of 1,939 acres (see Figure 8). About 40 percent of the TRZ acreage was zoned as residential, with most of the remainder being vacant and zoned as either commercial or agricultural.47 Based on the amount of potentially developable land, the construction of Eastlake Boulevard Extension Phase 2 was expected to create a significant amount of growth, which would in turn generate the TRZ revenues needed to pay for the town’s share of the project cost.

In spring 2013, an unexpected change in ownership of a large parcel within the TRZ (a private golf course) created a situation that led the Town Council to rescind TRZ No.1 and adopt a new TRZ with revised boundaries. The Horizon Regional Municipal Utility District (HRMUD), a local government unit that provides water utility services to Horizon City, acquired the golf course to facilitate disposal of its treated wastewater. The change in ownership from private to public meant the parcel become exempt from paying property taxes, creating the need to revise TRZ revenue estimates. After rescinding TRZ No.1, the Town of Horizon created TRZ No.2 with slightly revised boundaries and adopted it by ordinance in December of 2014. TRZ No. 2 was expected to generate revenues to finance up to $6 million dollars in project costs, approximately the amount needed by Horizon City to meet its cost share for the Eastlake Boulevard Extension Phase 2.49

Figure 9. Town of Horizon City TRZ No. 2 and Eastlake Blvd. Extension Phase 245

The Eastlake Boulevard Extension Phase 2 Project relied exclusively on local entities and local funding, which allowed the project to move rapidly from design through construction.49 Starting in 2015, a series of interlocal agreements were signed between and among the 2013 El Paso County CMP partners.50 First, El Paso County and CRRMA signed an interlocal agreement providing CRRMA with access to the county’s VRF revenues to issue bonds and tasking it with developing (designing and building) a slate of the county’s 2013 CMP projects.51

In November 2016, Horizon City signed a three-party interlocal agreement with El Paso County and CRRMA.52 The agreement provided for the development and financing of Horizon City’s local share of Eastlake Boulevard Extension Phase 2. The agreement committed CRRMA and El Paso County to fund the Horizon City’s share of project costs using county VRF proceeds. The town committed to repay CRRMA principal and interest using TRZ No. 2 revenues over a period of 18 years and to acquire the right-of-way for the project. The county funded its share of the project using VRF revenues. Finally, CRRMA served as the vehicle to issue bonds backed by the county VRFs, and as the clearinghouse to reimburse the county for the portion of the VRFs using revenues from Horizon City’s TRZ No. 2.49

This unique arrangement allowed Horizon City to move from project planning through design and construction in less than 5 years. The project was completed 9 months ahead of the original schedule and under budget.53 The financing plan was partly responsible for this for two reasons. First, the town avoided issuing its own TRZ revenue bonds, which would have been more costly because of the risk associated with the real estate market. Second, the town did not have a need to pursue a Texas DOT State Infrastructure Bank loan, which would have delayed the project by forcing it to go through the Federal review process.49 The milestones below provide a comprehensive picture of the project timeline:

In addition, the development agreement with a single executing agency—CRRMA—and the accelerated schedule enabled El Paso County and the Town of Horizon City to benefit from project cost savings.49 While the initial cost estimate called for a project cost of just over $19 million, the actual cost to completion was $16.7 million, resulting in a savings of about $2.3 million. Tables 9 and 10 provide the initial and final cost estimates for the project design and construction, and the funding breakdown between the County of El Paso (77.3 percent) and the Town of Horizon City (22.7 percent).49

Item |

Estimated Cost |

County Portion |

Horizon City Portion |

|---|---|---|---|

Engineering and Environmental |

$2,269,525 |

$1,754,343 |

$515,182 |

Construction |

$16,785,565 |

$12,975,242 |

$3,810,323 |

Total Estimate |

$19,055,090 |

$14,729,585 |

$4,325,505 |

Item |

Estimated Cost |

County Portion |

Horizon City Portion |

|---|---|---|---|

Engineering and Environmental |

$1,536,643 |

$1,187,825 |

$348,818 |

Construction |

$15,143,338 |

$11,705,800 |

$3,437,538 |

Maintenance (10/2018 – 5/2019) |

$42,073 |

$32,523 |

$9,551 |

Total Estimate |

$16,722,054 |

$12,926,148 |

$3,795,906 |

The Eastlake Boulevard Phase 2 Extension Project is an example of effective cooperation among local government agencies to improve regional mobility and transportation infrastructure. The County of El Paso and the Town of Horizon City were confronted with an urgent need to improve their transportation infrastructure, provide connectivity to the rest of the El Paso metropolitan area for its rapidly growing population, and generate economic development. The town’s leadership saw an opportunity to advance its economic goals through the transportation investments envisioned in the 2013 El Paso County CMP, and despite being a small and young community, took the bold steps of using a relatively new funding tool in the form of a TRZ and negotiated a unique funding and development agreement with other local entities to make the project happen.54

However, this process was not easy and required forging partnerships and developing trusting relationships with other local entities, as well as implementing management processes and tools, such as a CIP, to allow it to effectively manage its growing capital improvement project portfolio. The CIP allows the town to understand and plan more effectively the Eastlake Boulevard Extension Phase 2 Project financing agreement, as well its growing list of other capital projects.54

The Town of Horizon City’s City Charter requires a 3-year CIP that is presented to the Council twice a year—once in May for review and again in September for final adoption. As the town has continued refining its process for developing their CIP, they have added projects with longer planning horizons to coordinate with requests made to the MPO. Furthermore, the additional projects reflect the council’s recognition that many capital projects require long lead times for development.

More specifically, as the town worked to develop the Eastlake Extension Phase 2 Project, it encountered both internal and external challenges that had to be addressed, and which resulted in other lessons learned for the future. Table 12 describes these challenges and how the town addressed them, and summarizes the lessons learned.54

Challenge |

Description |

Lesson Learned |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Internal Challenges |

||||

Introducing new funding concept to policymakers |

Introducing TRZs, a then little-known funding source, to the City Council was an important step since they would have to vote in favor of directing the increment to fund the specific transportation project. The 2013 CMP was largely conceived and developed externally by the County of El Paso and other regional agencies, so bringing the plan to the City Council required coordination to present the concept of value capture and its specific application to the project. Coordination with Town finance also had to occur. |

Plan project development with plenty of time to allow for ongoing discussions with policymakers and key municipal staff. Particularly when the municipality is new to the funding source, policymakers must be comfortable with the concepts and have time to explore different scenarios and ask questions about funding projections and project development. |

||

Determining zone size |

Determining the right buffer size for the zone is usually a balancing act for municipalities. The zone should be adequate to cover contingencies that may arise as the TRZ-funded projects are developed; however, the zone should not be so unnecessarily large that the municipality risks over-committing its future general revenue fund, and decreasing its ability to fund basic services. The town worked with the Texas A&M Transportation Institute to develop the buffer it believed to be most appropriate for this specific situation. |

CIP managers must work with the municipalities’ financial staff and team analyzing zone projected revenues to size the zone appropriately. |

||

External Challenges |

||||

Coordinating with external partners |

As the first agreement of its kind, coordination with the County of El Paso and CRRMA under the 2013 CMP was critical. Staff and Town of Horizon City policymakers met with county leaders and county management repeatedly to discuss the project, the town’s commitment to its funding share, and the three-party agreement and the participating parties’ responsibilities. |

Communication with partner agencies is critical to project success. Designate a team to lead those discussions so conversations are consistent and ongoing. |

||

Right-of-way acquisition |

The town committed to securing the necessary right-of-way for the extension. Three distinct property owners were involved, and the town worked to secure either rights-of-way or permanent easements. Working with property owners and utility companies was critical to maintain the project on schedule, so Town staff worked to meet with property owners and the design team to secure the necessary right-of-way for the road construction. |

Work with property owners as early as possible in project development to begin negotiations and work on property transfers. |

||

Changes in property designation |

While the TRZ’s financial analysis anticipated that the land use could change to commercial, the models did not anticipate that a significant change from private to public ownership would occur, yet it did. The golf course sale from private ownership to the HRMUD was material enough for the town that it determined the best approach was to recalibrate the financial analysis and re-establish the TRZ so the golf course as a public property was no longer included in the zone. Fortunately, the timing of the project was not negatively affected by the creation of TRZ No. 2. |

Expect the unexpected and be prepared to deal with it. |

||

[xxi] VA Code § 15.2-4603 (2019).