TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF FIGURES

LIST OF TABLES

DIFs have expanded and evolved substantially throughout the United States over recent decades and currently appear in many different forms covering a wide range of infrastructure types with varying degree of applications around the country. These changes have taken place through State or local legislation, regulations, and numerous court cases. Although the process has at times been challenging and complex with much debate over specifics, the underlying fee principles are now better defined and more straightforward than ever—perhaps one reason why DIFs have grown substantially in many communities.

The legal underpinning of DIFs are based primarily on the essential nexus and rough proportionality requirements associated with exactions in general, stemming from the rulings from two landmark U.S. Supreme Court cases—Nollan v. California Coastal Commission (1987)18 and Dolan v. City of Tigard (1994).19 Because DIFs will likely continue to be contested in the future regardless of these rulings, it is beneficial to have some understanding of past legal challenges and of how DIFs have evolved over the years in response. Overall, the legal evolution of DIFs can be divided into three periods: (1) pre-Nollan/Dolan, (2) Nollan/Dolan, and (3) post-Nollan/Dolan.

In the absence of explicit State enabling legislation, many public agencies originally developed impact fees as a form of monetary exaction. Pre-Nollan/Dolan, local agencies originally defended the legal basis for impact fees as an exercise of local government's broad police power—one of the trinity of powers that distinguishes government from private organization20—to protect the health, safety, and welfare of the community. Local governments generally considered exactions to represent an exercise of police power because, when properly applied, they engender a legitimate governmental (public) interest.

In the pre-Nollan/Dolan period, before the 1990s, lawsuits and subsequent court rulings often determined public agencies’ ability to collect exactions. Unlike in the decades prior to the 1990s, when courts mostly ruled in favor of public agencies, the basic trend since then has been for courts to lean in favor of stronger legal rights for property owners (which, in this case, includes developers), making public agencies moderate their regulatory position on exactions. This shift in the courts, after the Nollan/Dolan rulings, was also due in large part to public agencies’ heightened use of DIFs, which was brought about by strong resistance to property tax increases in general and a continued decline in Federal funding.

The most important legal aspects to police power involving exactions in the pre-Nollan/Dolan period were the constitutional arguments against zoning; that is, zoning failed to meet the constitutional guarantees associated with the due process, equal protection, and takings (or just compensation) clauses.21 Due process guarantees generally involved both procedural (e.g., whether local jurisdictions provided appropriate notice, proper hearing, timely permitting) and substantive (e.g., whether zoning is a legitimate use of the police power) issues. Under equal protection, the primary legal issue was whether a zoning ordinance favored certain property owners over others.

The most contentious and difficult legal challenge regarding zoning and exactions under police power, however, was the takings (also known as just compensation) clause. The constitutional protection against taking property without just compensation usually applies to situations in which a government agency physically takes a property (i.e., through eminent domain). Additional complexities arise, however, when a regulatory taking occurs and when the government imposes (1) a regulation (e.g., downzoning) that limits the owner's use of that property or (2) exactions on specific groups to pay for an improvement that benefits not only the group but the larger public (Rappa 2002).

The Nollan (1987) and Dolan (1994) rulings directly addressed these regulatory takings concerns on exactions and for overarching guidance on their justification and accountability. These two cases established that in order to collect exactions (1) there needs to be a direct relationship between the project proposed and the exaction required (referred to as the essential nexus test per Nollan) and (2) the exaction must be roughly proportional to the impact created by the project (referred to as the rough proportionality test per Dolan). Following the Nollan decision in 1987, several States began adopting impact fee-enabling legislation to facilitate localities’ ability to implement DIFs: first, Texas in 1987, followed by Illinois in 1988, and then California and New Jersey in 1989. As of 2015, 29 States had established enabling legislation for DIFs (FHWA 2019, 34).

To pass the Nollan/Dolan tests, public agencies began commissioning what is now called a nexus (or fee) study to demonstrate a legal basis for the required nexus and to develop a quantitative basis for specific impact fee levels that are proportional. A strong nexus study, along with robust State and/or local enabling legislation helps defend the use of DIFs. Especially for new developments, however, impact fees vary widely due to the significant variations in the level of concessions developers provide that often depend on the local economic conditions and political climate (Fulton and Shigley 2012).

It is important to note that, pre-Nollan/Dolan, there had been numerous lower court rulings that established a reasonable relationship standards for exactions based on police power (specifically, per the Fourteenth Amendment).22 Although the courts, in the post-Nollan/Dolan period, have made it clear that lawful impact fees must meet the stricter Nollan/Dolan standards, the courts have also accepted very relaxed approaches, including the common use of flat fees set at average levels applied uniformly throughout the community (HUD 2008, ii). As presented earlier, as long as the process achieves an overall, reasonable correspondence between costs and fees, it is legally accepted as an impact fee.

The California Supreme Court ruling on the Ehrlich v. Culver City(1996) case23 helped to establish an additional and more inclusive test for exactions by reconciling the elements of the stricter Nollan/Dolan essential nexus/rough proportionality test with the pre-Nollan/Dolanreasonable relationship test, which had already been codified into the California State legislation (Kim 2018, 19). The Ehrlich ruling has been significant in two respects: (1) local jurisdictions must also apply a Nollan/Dolan analysis to monetary exactions (i.e., in the form of fees, including DIFs, as opposed to land dedication or in-kind facility/service provisions) and (2) only those fees specifically imposed on a particular project were entitled to be judged by the heightened Nollan/Dolan criteria, with other generally applicable fees being tested under a reasonable basis.

The Ehrlich ruling served as an important precedent for the U.S. Supreme Court’s more recent ruling on Koontz v. St. John River Management District (2013),24 the third landmark case on exactions. The Koontz ruling further clarified Nollan/Dolan decisions by (1) expanding the application of the Nollan/Dolan test to include monetary exactions explicitly and (2) allowing lower courts to resolve the applicability of legislative exactions (i.e., pertaining to entire areas of cities or more programmatic applications) while making it clear that Nollan/Dolan tests are applicable for adjudicative exactions (i.e., pertaining to individual parcels or project-specific disputes; Wake and Bona 2015, 559–562).

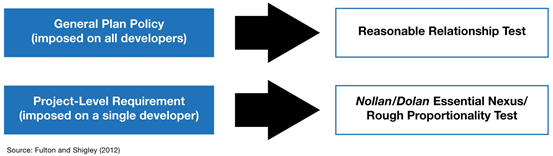

Figure 2 provides an overall relationship test guideline for exactions as relates to all three landmark cases (i.e., Nollan 1987, Dolan 1994, and Koontz 2013). As shown, the reasonable relationship test is considered sufficient for exactions that are imposed on all developers as part of a broad policy scheme, whereas the stricter essential nexus and rough proportionality test should probably be used when exactions are imposed on a single developer. Transportation agencies considering the use of DIFs should consult with their own counsel to make sure that the DIF is structured to pass a legal challenge should that occur.

Figure 2. Chart. Nollan/Dolan/Koontz Relationship Test Guidelines for Exactions.

More generally, public agencies’ experimentation with impact fees has been paralleled by increasing State court involvement in the review of these fees. A general trend in State courts has been to require a "rational nexus" between the fee and the public improvement needs created by development as well as the benefits incurred by the development. This analysis is a moderate position between a standard that requires that the fee be "specifically and uniquely attributable" to the needs a new development creates and the relaxed standard that the fee be "reasonably related" to the needs a development makes (APA 1997).

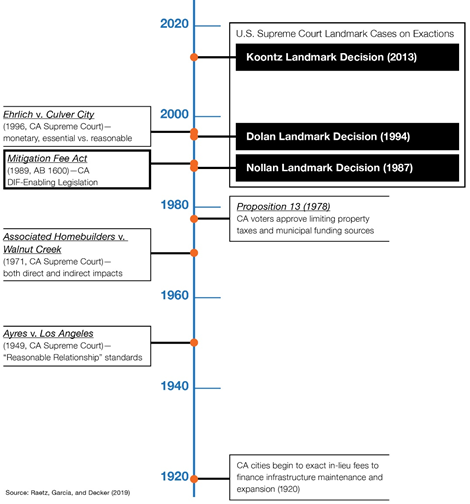

Figure 3 summarizes the overall evolution of DIFs in terms of legal challenges and court rulings as presented earlier. The timeline shown is for California specifically, but it could be considered generally representative of a typical sequence of events from the legal perspective at other States.25

In summary, working back from the beginning, fee-based exactions (i.e., in-lieu fees instead of land dedications) in California started as early as in the 1920s, falling under the police power granted to cities and counties in Article 11 of the California Constitution. These fees went largely unchecked until State courts required a reasonable relationship test in Ayres v. City Council of Los Angeles in 1949.26 The California Supreme Court later expanded the eligible fee uses significantly in Associated Homebuilders Inc. v. City of Walnut Creek in 1971,27 with the ruling that development fees could also be used to mitigate indirect as well as direct impacts. In short, before Proposition 13 in the late 1970s, in which voters imposed significant restrictions on the ability of local governments in California to raise property taxes, the courts had generally ruled in favor of exactions under the police power doctrine.

Figure 3. Illustration. DIF Legal Evolution/Timeline—California Example.

After Proposition 13, public agencies in California started to increasingly use DIFs to make up for the significant loss in property tax revenues. Throughout the United States, outside of California, local governments also relied on DIFs as the resistance to property tax increases gained strong support. As a result, courts became much more restrictive, which precipitated the two landmark Nollan (1987)/Dolan (1994) decisions by the U.S. Supreme Court described earlier. Soon after the Nollan decision, California was one of the first States to adopt the impact fee-enabling legislation, the Mitigation Fee Act (MFA) of 1989 (Assembly Bill 1600), which was meant to regulate impact fees more stringently.28 Finally, the Ehrlich case in 1996, presented earlier, helped to resolve potential conflict between the reasonable relationship and stricter Nollan/Dolan standards, which culminated in the Koontz landmark decision by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2013.

Policy experience with DIFs has been highly diverse from State to State. Some have statewide enabling legislation that broadly allows local authorities to impose impact fees, whereas other States grant authority only to certain localities. In most States, DIF policies have evolved through the specific court-tested efforts of individual local jurisdictions to generate funds needed to provide public services. As of 2015, 29 States had passed statewide legislation that affects the ability of local agencies to levy DIFs (FHWA 2019). State DIF legislation is generally intended to codify existing constitutional and decisional law regarding impact fees and exactions; that is, previous court decisions that had already shaped the law in each State.

The development of DIF legislation across States has been asymmetric and diverse, ranging from very specific and restrictive yet comprehensive—as is the case for Texas—to very brief and general—such as the legislation in Indiana. Texas, cited as having the first DIF legislation, specifies not only the procedure for calculating fees but also the formulas to use as well as the recalculation and refund requirements (HUD 2008).29 Indiana, on the other hand, specifies a single and unified impact fee for each new development.30

For some States, such as New Mexico and Indiana, statewide DIF statutes have been largely motivated by the need to address their critical affordable housing issues. In general, most States allow the use of DIFs for improvements related to water/sewer/stormwater, roads, parks/libraries, schools, and police/fire. Although DIFs use is more prevalent for water/wastewater, several States emphasize DIFs specifically for transportation infrastructure, in some cases through the establishment of various forms of transportation districts.

Oregon’s DIF-enabling legislation, for example, clearly states local communities’ ability to use Transportation SDC(TSDC) for public transportation.31 Illinois’ DIF Statute adopted in 1988 allows collection of transportation impact fees for roads that are directly affected by traffic demands generated by new development (Carrión and Libby 2000, 8).32 In New Jersey, the Transportation Development District Act of 1989 allows the creation of transportation improvement districts (TID) and transportation development districts (Carrión and Libby 2000, 8).33 The New Jersey DOT forms districts upon the petition of local officials. The legislation provides for the development of a master traffic plan to measure the extent of existing deficiencies and the impact of future development. Impact fees may then be charged to new developments based on specific impacts and any projects necessary to offset the impacts.

California and Florida have the highest use of DIFs, but these States have had very different experiences in terms of their DIF legislative needs. In California, as described earlier, the ability to impose DIFs was largely determined by established case law until the MFA in 1989, which was enacted soon after the 1987 Nollan ruling.34 The MFA (Assembly Bill 1600), which became effective on January 1, 1989, is broad in its language, allowing local governments to use impact fees on capital projects that are reasonably related to increased demand for public facilities, but specific about the way that impact fees are imposed on development projects.35 For example, the agency imposing the fee must:

Currently, the MFA, together with established case law, regulates how local agencies set and report on impact fees.

In contrast, Florida did not have State DIF-enabling legislation until 2006 (Mathur and Smith 2013, 19).36 Its DIF legislation is brief and does not specify eligible uses for impact fee funding, leaving those decisions to public agencies. As such, two other pieces of State legislation have largely determined local imposition of DIFs:

For the transportation sector specifically, as the Concurrency rule39 fell short in addressing congestion, Florida adopted the Community Planning Act in 2011, which removed the transportation concurrency requirement to allow an alternative mobility fee funding system, a form of DIF program.40 As of 2016, more than 20 local jurisdictions in Florida have implemented mobility fee programs (Renaissance Planning 2017).

For some States, DIF-enabling legislation has very limited application. Arkansas, for example, adopted a State enabling fee act in 2003 that only applies to the water/wastewater sector for municipalities and excludes DIF authority for counties altogether (HUD 2008, 38).41 In other States with no statewide DIF legislation, such as Tennessee and North Carolina, impact fees and development taxes are generally authorized for individual jurisdictions through special acts of the State legislature (HUD 2008, 37). For example, Kentucky has no DIF-enabling legislation but allows an open space mitigation fee specifically for Lexington-Fayette County as part of the county’s zoning ordinance.

For many States, DIFs were commonly used by home-rule (charter) cities42 long before the passage of State DIF legislation (HUD 2008, 95). Colorado’s long history of DIF uses by home-rule cities eventually evolved into the State DIF legislation that passed in 2001.43 Ohio has no specific State DIF-enabling legislation, but home-rule cities (as well as other general law cities) have a long history with sewer tap or connection fees, excise taxes, and other local charges on new developments. The Ohio Supreme Court affirmed these charges, which are effective as long as the State legislature does not issue an express or implied prohibition of the fees. They are still subject to constitutional tests of equal protection and due process (Carrión and Libby 2000, 9–11).

Rulings at the State court level have generally defined how DIFs may be applied and used at the local level. Thus, there are numerous authorities and guidelines available to assist local and regional agencies in the planning processes that must be undertaken to develop a legally defensible DIF program. For some cities, such as San Francisco, the local-enabling ordinance preceded the State enabling act, whereas for others, DIF ordinances pertaining to specific project cases operationalize the authority granted by the State statutes.

After Nollan/Dolan, the government—rather than the developer—has generally borne the burden of proof to show that the fee bears a reasonable relationship to the impact of the proposed development. However, once the locality enacts the proper legislative fee, the burden shifts to the developer to show that the fee either fails to advance a legitimate State interest or deprives the developer of any viable economic use of its land (LCC 2003, 6; Raetz, Garcia, and Decker 2019, 18). The locality's burden of proof on the legitimacy of DIFs is met through legislatively enacted findings (that precede DIF program enactment), which generally comply with the State DIF statute.44

Local ordinances generally provide details on the uses of DIFs, including whether the fees are exclusively for capital expenditures or whether they may be used for operations, maintenance, and/or other administrative expenses. Although the local statutes also specify the projects that are eligible for impact fee funding, the details on eligibility vary at the State level. California and Oregon statutes, for example, specify project eligibility, whereas the Florida statute does not, thus leading to concerns that the Florida DIF statute could be amended to potentially limit the extent of eligible projects in which impact fees can be charged based on the current authority granted to public agencies (Mathur and Smith 2013, 20).

Although the Florida State statutes are ambiguous on the types of expenses eligible for DIF funding, the local statutes are clear. For example, in the City of Aventura, its Code of Ordinances operationalize the City’s authority to charge a transportation mitigation impact fee.45 The Code specifically allows impact fee use for the expansion, operation, and maintenance of the City’s public transportation system. Furthermore, it specifies 3 percent of fee revenues can be used for the cost of administering the impact fee program (Mathur and Smith 2013, 20). Broward County operationalized its DIF authority46 through the County Land Development Code, which specifies that the fee can be used for capital as well as operating expenditures with 2 percent set aside for administration expenses (Mathur and Smith 2013, 19).

In California, the City of San Francisco originally enacted the transportation impact development fee(TIDF) in 1981 through a local ordinance that the San Francisco County Board of Supervisors passed. The ordinance is now covered in Article 4 of the San Francisco Planning Code and allows the TIDF to fund capital, operations, maintenance, and overhead costs. Only nonresidential users pay the fee, and specific properties are exempt, including those in specific redevelopment areas (e.g., those used for warehousing and recreation or owned by the city, State, or Federal governments). This local statute was passed without the benefit of State enabling legislation and was, therefore, vulnerable to legal challenges. The most critical one was the 1981 class-action lawsuit in Russ Building Partnership v. City and County of San Francisco, in which the city successfully defended the local statute and the fee was upheld in the courts.47

Although cities big and small in California have historically relied on impact fees for almost 100 years, their experiences have varied significantly. Unlike San Francisco, for example, some larger and more urbanized cities, such as Los Angeles and Oakland, only recently established substantial citywide impact fee structures for residential projects (Raetz, Garcia, and Decker 2019, 20). In 2015, the Los Angeles City Controller released an audit of the city’s impact fees, calling for broader use and better management of the fees, noting that the city might be missing out on as much as $91 million per year in potential revenue from commercial, industrial, and residential development. Since then, Los Angeles has established citywide parks and affordable housing impact fees. The City of Oakland’s recent decision to implement a citywide impact fee structure—covering affordable housing, transportation, and capital improvement costs—was motivated in part by the recent court decisions that restricted the reach of its inclusionary zoning program to for-sale projects.

In Oregon, Portland operationalized the city’s authority to charge a TSDC through its City Code to fund multimodal transportation improvements and associated bus and transit improvements, sidewalks, bicycle paths, and pedestrian facilities.48 Further, in operationalizing the State statute, the Code explicitly prohibits the use of the fee for maintenance and repairs, and for the purchase or maintenance of rolling stock (e.g., buses, railcars, etc.; Mathur and Smith 2013, 18).49

In Ohio, even without the State enabling legislation, the City of Beavercreek has had a formal impact fee ordinance since 1993. For transportation improvements, the city defined a special impact fee district to provide new streets, roads, and related traffic facilities needed for new developments. The fee is paid at the time of application for a zoning permit or final residential plat approval concerning the land to be developed within the special district. Funds collected from the developers goes into a special trust fund, and no funds may be used for maintenance. The impact fee ordinance was intended to shift an appropriate share of the cost of new roads and streets onto the new development (Carrión and Libby 2000, 10–11).

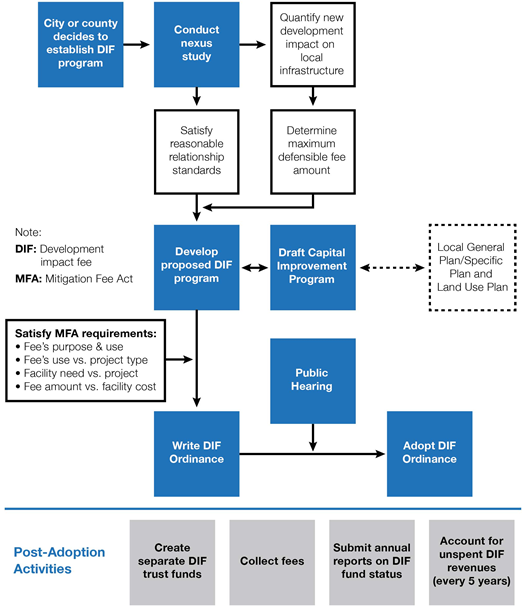

As a representative example, depicts the local DIF implementation process and basic steps involved in establishing local a DIF ordinance for cities and counties in California (see chapter 6 for additional details on DIF implementation processes).

Figure 4. Chart. Legislative Process for Local DIF Ordinance—California Example.

As shown, a city or county first selects DIF as their choice of VC techniques to raise revenues and decides to establish a new impact fee. A locality can typically satisfy the reasonable relationship standard required by the State DIF-enabling legislation (in this case, the MFA) by conducting a nexus study. This study quantifies the impact of new development on local infrastructure and determines its cost, which is considered the maximum legally defensible fee amount. Exceeding this maximum fee ceiling could leave the locality vulnerable to litigation (Raetz, Garcia, and Decker 2019, 20).

Localities often draft CIPs in concert with their proposed fee program. CIPs generally establish the basic plan for the construction and financing of public facilities within a jurisdiction. In California, as in many other States, the use of CIPs is encouraged (though not required) by the State DIF legislation to help set out the planned use of DIF revenues for improvements related to new developments. Nexus studies, particularly when combined with CIPs, help strengthen the required findings in establishing or increasing a fee as specified in the State DIF statute.

Once the locality meets the State requirements, it can then draft the DIF ordinance. As required by California’s MFA, the locality must hold at least one public hearing and get feedback before formally adopting the ordinance (Raetz, Garcia, and Decker 2019, 20).50 The MFA also stipulates other critical postadoption administrative needs, including:

17 Unless otherwise specifically noted, the primary source of the key discussions provided in this section come from Barclay and Gray (2020).

18 Nollan v. California Coastal Commission, 483 U.S. 825 (1987), https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/483/825/.

19 Dolan v. City of Tigard, 512 U.S. 374 (1994), https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/512/374/.

20 The other two are the authority to tax and the power to take property under eminent domain.

21 Due process clause is contained in both the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution, equal rights clause in the Fourteenth Amendment, and just compensation or takings clause in the Fifth Amendment.

22 The reasonable relationship test requires that there is a reasonable connection between the fee charged to the developer and the needs that development generates. In addition, lower courts have also expounded on a “specifically and uniquely attributable” test that requires that the fee charged to the developer is directly and uniquely attributable to that development. See, for example, Ayres v. City Council of Los Angeles (1949), 34 Cal.2d 31, https://law.justia.com/cases/california/supreme-court/2d/34/31.html.

23 Ehrlich v. City of Culver City (1996), 12 Cal. 4th 854, 50 Cal. Rptr. 2d 242, 911 P.2d 429, https://law.justia.com/cases/california/supreme-court/4th/12/854.html.

24 Koontz v. St. Johns River Water Management Dist., 570 U.S. 595 (2013), https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/570/595/.

25 As was the case for both Nollan and Koontz, California has been one of the States making the most use of DIFs and has set several legal precedents that led to the U.S. Supreme Court landmark decisions on exactions and impact fees.

26 Ayres v. City Council of Los Angeles, 34 Cal.2d 31, 207 P.2d 1, 11 A.L.R.2d 503, https://law.justia.com/cases/california/supreme-court/2d/34/31.html.

27 Associated Home Builders etc., Inc. v. City of Walnut Creek (1971) 4 Cal.3d 633, 639-647, https://law.justia.com/cases/california/supreme-court/3d/4/633.html.

28 California Government Code §§ 66000-66025.

29 Tex. Local Gov't Code § 395.001 et seq. Since its original enactment in 1987, the Texas DIF statute was amended in 2001 to (1) provide credit when alternative funding is available, (2) increase the road impact fee service area (from 3 to 6 miles), (3) increase the mandatory update period (from 3 to 5 years), (4) eliminate the recalculation requirement, and (5) decrease the number of public hearings for fee update (from two to one).

30 Ind. Code § 36-7-4-1300 et seq.

31 ORS 223.299. In this case, for capital improvements only.

32 605 Ill. Comp. Stat. § 5/5-901 et seq.

33 N.J. Rev. Stat. § 27:1C-1 et seq.

34 Cal. Gov. Code § 66000 et seq.

35 Additionally, the MFA specifically allows the use of impact fees for transportation-related improvements but does not specify whether their use is exclusively for capital expenditures or also for operations and maintenance expenses. Also, as presented in table 1 in chapter 2, the MFA explicitly excludes Quimby Act in-lieu fees for parks, fees covering the cost of processing applications, or fees collected under development agreements.

36 Fla. Stat. § 163.31801.

37 Laws of Florida Ch. 85-55. This law made substantial revisions to §§ 163.3161–163.3211.

38 Fla. Stat. § 163.3180.

39 For a development to "be concurrent" or "meet concurrency,” the local government must have enough infrastructure capacity to serve each proposed development.

40 Laws of Florida Ch. 2011-139. This law made substantial revisions and additions to §§ 163.3161–163.3247. With the removal of the transportation concurrency requirement, Florida Legislature has encouraged the adoption of mobility fees if local government repeals transportation concurrency (Renaissance Planning 2017).

41 Ark. Code § 14-56-103.

42 A home-rule or charter city has the ability (as granted by its State) to pass its own laws to govern itself as it sees fit so long as it obeys the State and Federal Constitutions. Because of their relative legislative independences, home-rule cities are better positioned to use DIFs without the State enabling legislation.

43 Colo. Rev. Stat. § 29-1-801 et seq.

44 As will be presented in chapter 6, involvement by the City Attorney is crucial throughout the DIF implementation process.

45 Chapter 2, Article 4, Division 5, § 2-302.

46 § 27.40. DIF in this case is in the form of transportation concurrency fee because the county has chosen to require transportation concurrency.

47 Russ Bldg. Partnership v. City and County of San Francisco (1987) 199 Cal.App.3d 1496, 1504.

48 Chapter 17.15.

49 Chapter 17.15.100.B.3.

50 Cal. Gov. Code § 66018.

51 Cal. Gov. Code § 66006(a).

52 Cal. Gov. Code § 66017(a).

53 Cal. Gov. Code § 66006(b).

54 Cal. Gov. Code §66001(d)).The MFA also includes a mechanism by which a party can protest an impact fee. When a local agency approves a development project or imposes the fee, the agency must send a notice of the fee amount and a 90-day window to file any legal protest. When protesting, the applicant must still pay the fee in full (or show evidence of arrangements to pay the fee when due), as well as serving a notice outlining the reason for their protest. If the court invalidates a fee ordinance or finds in favor of the plaintiff, the local agency at fault must refund the unlawful portion of the fee plus interest (Cal. Gov. Code §§ 66020–66022). Also, the protesting party may request an independent audit at his or her own expense (Cal. Gov. Code § 66023).