CONTENTS

FIGURES

TABLE

In Texas, municipalities may establish transportation reinvestment zones (TRZs) to fund projects, which are like tax increment finance zones, solely for transportation. The municipality designates a contiguous zone in which it will promote a specified transportation project. Once the zone is created, a base year is established and the incremental increase (or a portion of the increase) in property tax revenue accruing to the municipality from this area is designated as a tax increment that is used to partially fund the transportation project's capital cost. The proposed zone must be deemed underdeveloped and the TRZ must (1) promote public safety; (2) facilitate the improvement, development, or redevelopment of property; (3) facilitate the movement of traffic; and (4) enhance the local entity's ability to sponsor transportation projects. TRZs can be established by municipalities only, not by counties. A municipality could use TRZ revenues to fund their share of a county or State project.84

In 2007, Senate Bill 1266 amended chapter 222 of the Texas Transportation Code, providing legal context for TRZs (sections 222.105–222.107) to address funding shortcomings for transportation projects throughout the State. Since then, TRZ legislation has evolved to remedy some technical issues related to project definition, boundary changes (limits), and the ability to rescind pledges. The legislation also was expanded to be applicable to rail, transit, parking lots, ferries, airports, and port and navigation projects.85

TRZs can be established at the municipal level only. TRZs have confronted implementation issues related to the issuance of an opinion by the Texas Attorney General stating that their use could be subject to challenge under the "equal and uniform taxation" requirement of the Texas Constitution. An amendment to the Texas Constitution was passed to exempt municipalities from the constitutional requirement for equal and uniform property taxation with regard to TRZs. No similar provision was made to exempt counties.86

The City of El Paso adopted TRZs to generate revenue for $403 million in Interstate 10 projects that had been identified in their 2008 comprehensive management plan. The value-creating investments included interchange improvements, new connections between existing roadways, new roadways, safety and pedestrian access improvements, and aesthetic and transit improvements to several corridors in the city. Funding sources for the investments included motor fuel tax funds, tolls, and TRZ revenue. Local partners involved in planning, funding, or otherwise supporting implementation of the TRZ projects included the City of El Paso, the Camino Real Regional Mobility Authority, El Paso's Metropolitan Planning Organization, the Texas Department of Transportation (DOT) – El Paso District, and local property owners.87

Caution should be taken when developing reinvestment zones given possible issues over the "equal and uniform taxation" clauses. In Texas, pursuant to an amendment to the State Constitution, counties cannot consider reinvestment zones; however, cities are authorized.

Local agencies can use reinvestment zones to gain more control over which projects get funded in their municipality in close collaboration with their State DOT and planning partners.88

Aldrete, R., S. Vadali, D. Sagaldo, S. Chandra, L. Cornejo, and A. Bujanda. 2016. Transportation Reinvestment Zones: Texas Legislative History and Implementation. Final Report. PRC 15-36F. College Station, Texas: Policy Research Center, Texas Transportation Institute.

Attorney General of Texas. 2014, August 14. Opinion No. GA-1076.

Attorney General of Texas, Ken Paxton. 2015, February 26. Letter to the Honorable Joseph C. Pickett, Chair, House Committee on Transportation, Texas House of Representatives.

Reeves, Kimberly. Texas AG opinion barring use of transportation reinvestment zones to fund roads draws flak. 2015, February 27. Austin Business Journal. Retrieved on March 21, 2017. http://www.bizjournals.com/austin/blog/abj-at-the-capitol/2015/02/texas-ag-opinion-barring-use-of-reinvestment-zones.html.

Saginor, J., E. Dumbaugh, D. Ellis, and M. Xu. 2011. Leveraging Land Development Returns to Finance Transportation Infrastructure Improvements. UTCM Project #09-13-12. College Station, Texas: Texas Transportation Institute.

Texas Department of Transportation. n.d. Transportation Reinvestment Zones. Retrieved on March 21, 2017. http://www.txdot.gov/government/programs/trz.html.

Vadali, S. 2014. Using the Economic Value Created by Transportation to Fund Transportation. NCHRP Synthesis Report 459. Washington, DC: Transportation Research Board.

Vadali, S.R., R.M. Aldrete, and A. Bujanda. 2009. Financial model to assess value capture potential of a roadway project. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, No. 2115, pp. 1–11.

Vadali, S., R. Andrete, A. Bujanda, S. Swapni, B. Kuhn, T. Geiselbrecht, Y. Li, S. Lyle, M. Zhang, K. Dalton, and S. Tooley. 2010. Transportation Reinvestment Zone Handbook. FHWA/TX-11/0-6538-2. College Station, Texas: Texas Transportation Institute.

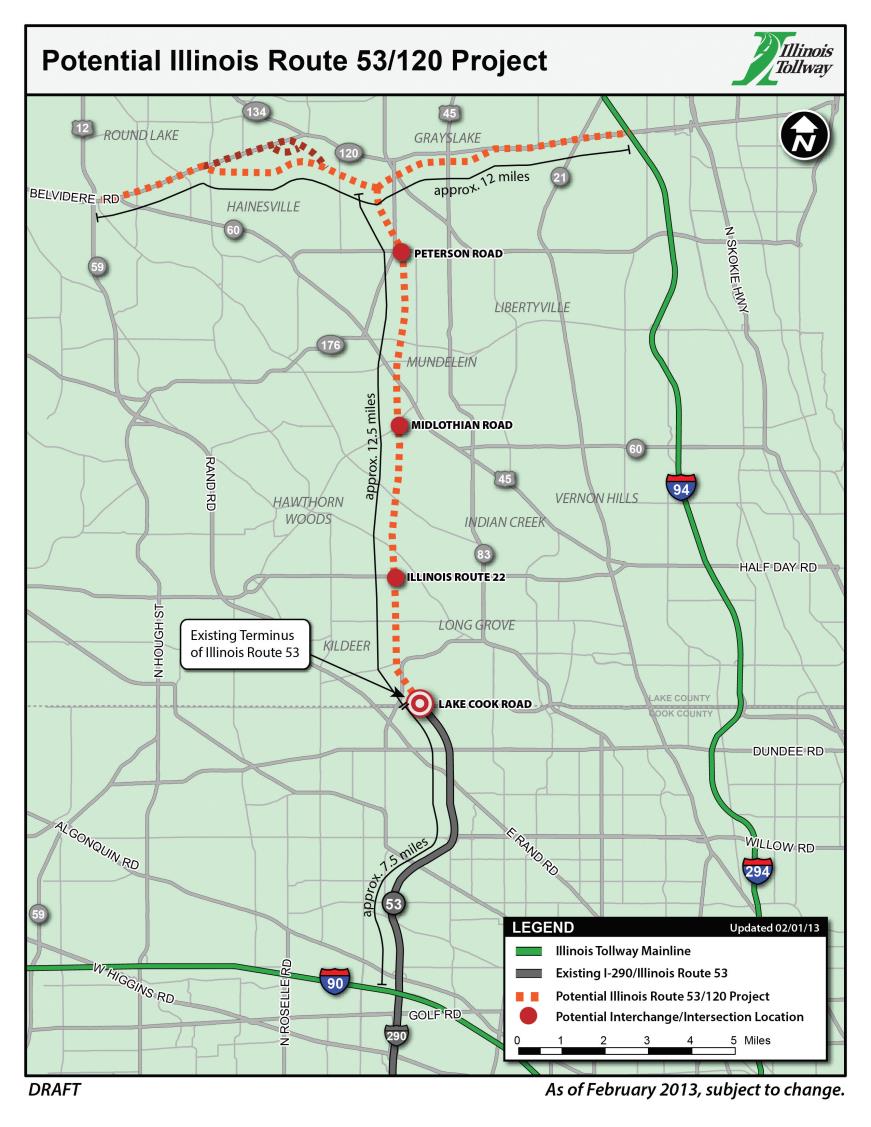

Figure 5. Canceled Illinois Route 53/120 project.89

Northwest of Chicago, north-south Interstate 290 (I–290) terminates at east-west Interstate 90 (I–90). Since the 1960s, transportation planners believed that some continuation of I–290 to the north of I–90 would be beneficial. In the late 1960s, Illinois Route 53 was constructed from I–90 north to Arlington Heights. In the late 1980s, it was extended further so that Route 53 extended 7.5 miles north of I–90. Between then and 2019, numerous planning efforts were undertaken to examine extending Route 53 an additional 12 miles north to east-west Route 120. Plans also were proposed to improve or bypass a 12-mile section of Route 120, the eastern portion of which would have an interchange with north-south Interstate 94. The planning effort was complicated because of the environmental sensitivity of some of the proposed right-of-way and due to the significant cost, estimated at about $2.7 billion. During the late planning phase, tax increment financing was being considered to partially fund Illinois Route 53/120.

In 2009, a local referendum was conducted. Seventy-six percent of the votes approved going forward with the project, although only about 21 percent of eligible voters actually participated in the referendum.

A 2015 feasibility study was tasked with determining a financially viable, fiscally sustainable, and equitable approach to fund the project. Toll revenue (based on $0.20/mile) was estimated to be capable of supporting between $250 million and $330 million in bonds. (Adding congestion-based tolls and additional tolls on nearby toll facilities could increase bonding capacity by an additional $380 million to $510 million.) However, even with enhanced tolling, TIF, and an additional county fuel tax, the Finance Committee could only envision revenues valued between $745 million and $993 million for a $2.7 billion project, leaving a substantial funding gap to be filled.

The 2015 study proposed a Sustainable Transportation Fund that would collect 25 percent of increased property taxes from non-residential parcels near the roadway. This TIF was estimated to provide financing for between $81 million and $108 million, which would be devoted to the Environmental Restoration and Stewardship Fund. These environmental safeguards and enhancements were critical for obtaining local political support for the project and were not eligible for funding from toll revenues pursuant to Illinois law.91

In 2016, some key local officials began to withdraw their support. Concerns included environmental issues, high proposed tolls, and the need for State or local tax revenues to fill the large funding gap.

In July 2019, the Illinois Tollway Authority

announced that they were stopping the $25 million environmental impact

statement that was underway due to a lack of consensus about the project and an

inability to develop an acceptable funding proposal. Over the five decades that

the Illinois Route 53 extension had been under consideration, the Illinois DOT

had spent $54 million acquiring about

1,100 acres of right-of-way. Illinois, Lake County, and some of its communities

will now decide what to do with the acquired right-of-way.

Scattershot suburban development in rural areas can overwhelm rural road capacity. Traffic congestion on rural roads was the impetus for this project.

Because the transportation system in the United States consists primarily of roads that do not impose tolls, creating new toll facilities (and increasing the tolls on existing toll facilities) is difficult because people object to tolls and introducing new tolls or increasing existing tolls often will divert some traffic from the toll facility onto nearby facilities without tolls.

The dispersed and low-density nature of

sprawl development requires extensive infrastructure expansion, the cost of

which may exceed the utility to users (as measured by potential user fees) and

to nearby landowners (as measured by potential increases in land values). TIF

revenues were limited to environmental protection. Aggressive proposed tolls,

combined with an additional county gas tax, were only able to generate

one-third (or less) of the estimated project costs, and no other source of

funds could be found to fill a funding gap of more than $1 billion. Even if

projected TIF revenues ($81 million to

$108 million) had been available for road construction, they would not have

come close to closing

this gap.

Although this was not studied, this project raises interesting questions:

Could there have been enough development demand near the proposed interchanges to generate tax revenues sufficient to fund the highway?

If that amount of development would occur, would it overwhelm the proposed highway and replicate the congestion that the facility was intended to resolve?

Community stakeholders were able to support a TIF concept for environmental protection and stewardship. Typically, TIFs are more popular than special assessments because it appears that TIFs do not entail any expenditure of existing revenue nor any increase in tax rates.93

As Tollway Ends Route 53 Extension Study, Now the Question: Do What With That Lake County Land? Daily Herald, July 15, 2019. https://www.dailyherald.com/news/20190712/as-tollway-ends-route-53-extension-study-now-the-question-do-what-with-that-lake-county-land.

Illinois Route 53/120 Feasibility Analysis. 2015, March.

Illinois Route 53/120 Project: Blue Ribbon Advisory

Council Resolution and Summary Report. 2012,

June 7. https://www.illinoistollway.com/documents/20184/96209/2012-06_FinalCouncilSummaryReport_web.pdf/4a6426bf-a46b-476e-bdee-bdc4b2d26d21.

Illinois Tax Increment Association. About TIF. http://www.illinois-tif.com/about-tif/.

Move Illinois. Illinois Route 53/120 Project Overview. https://www.illinoistollway.com/documents/20184/96146/IL_Route53_120_FactSheet_FINAL_081613.pdf/d704f34b-bdb2-4532-bb47-ec94c80f272c.

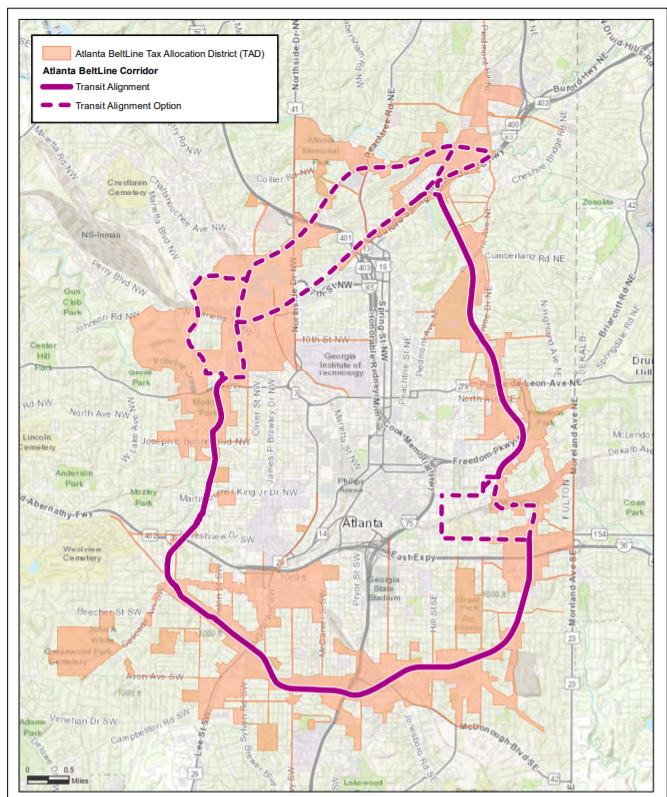

Figure 6. Atlanta BeltLine Tax Allocation District.94

The Atlanta BeltLine is a comprehensive transportation and economic development effort, and it is one of the Nation's largest urban redevelopment programs. By transforming Atlanta's mostly abandoned freight rail corridors, the completed BeltLine will ultimately include at least a 33-mile trail network and about 22 miles of transit. The full trail network and transit system are currently planned to be completed by 2030 and will ultimately connect 45 neighborhoods in Atlanta. The project is expected to generate $10 billion in total economic growth within the City of Atlanta, much of which will support ongoing project costs through a tax allocation district (TAD), which is the term for a TIF in Georgia.

When the TAD was created in 2005, properties around the proposed BeltLine generated limited tax revenue. To spur economic development, the City of Atlanta, Fulton County, and Atlanta Public Schools agreed to create a TAD on parcels surrounding this BeltLine's rail corridor. As investment increases around the BeltLine, this TAD generates tax revenue to support ongoing project delivery.

The City of Atlanta incorporated a legislatively directed goal of creating 5,600 units of affordable workforce housing over the TAD's lifespan, funded with TAD and other revenues. As of May 2021, 3,340 affordable units had been built within walking distance of the BeltLine.96

Alongside TAD revenue, other funding sources for the BeltLine include: the City of Atlanta; private investment and philanthropic contributions; county, regional, State, and Federal funding; and public-private partnerships. Ballot referenda in 2016 increased the local sales tax by 0.9 percent (from 8.0 to 8.9 percent) for transit and transportation projects within the City of Atlanta, a portion of which will fund some BeltLine transit, access, and the remaining right-of-way for the entirety of the 22-mile loop.

A 2005 forecast pegged total TAD revenues at $3 billion. Due to the Great Recession of 2007–2009 and other factors, total TAD revenues are expected to be much lower. More recent projections forecast that the TAD will generate about $1.6 billion from 2012 to its conclusion in 2030.97 In fiscal years 2008 through 2016, the TAD generated only $166 million.98

This funding shortfall led to the creation of a special service district (SSD) in 2021. The SSD is a special assessment district in which owners of about 5,000 commercial and multifamily property owners pay slightly more in property taxes ($2 per $1,000 of assessed value) to fund the completion of the BeltLine's 22-mile multiuse trail loop. Revenue from the SSD will be used to finance bonds that are expected to generate an estimated $100 million.99 Passage of the SSD is expected to unlock an additional $100 million in philanthropic matching contributions, as well as an anticipated $50 million in State and Federal grants. It is hoped that by ensuring the completion of the BeltLine's mainline trail, the SSD will enhance the TAD.

$4.8 billion (approximately $600 million spent through fiscal year 2019)100

In 2013, the Atlanta BeltLine organization published a Strategic Implementation Plan with the funding sources and amounts shown in table 1. Note that there is an $891 million funding gap.

| Funding Source | Amount (in millions) |

|---|---|

| TAD | $1,575 |

| Federal funds | $1,295 |

| City of Atlanta | $146 |

| Federal, State, regional, or local funding for streetscapes | $343 |

| Local funding for parks | $157 |

| Private philanthropic donations | $312 |

| Other | $11 |

| Unidentified (funding gap) | $891 |

| Total | $4,730 |

Atlanta BeltLine. 2013. Atlanta BeltLine 2030 Strategic Implementation Plan. Final Report. https://beltline.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Beltline_Implementation-Plan_web.pdf.

Atlanta BeltLine. The Project: Project Funding and Financials. https://beltline.org/the-project/project-funding/.

Atlanta Beltline. The Project: Special Service District (SSD). https://beltline.org/the-project/special-service-district/.

Federal Highway Administration. Case Studies: Atlanta BeltLine Tax Allocation District. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ipd/value_capture/case_studies/atlanta_beltline_tax_allocation_district.aspx.

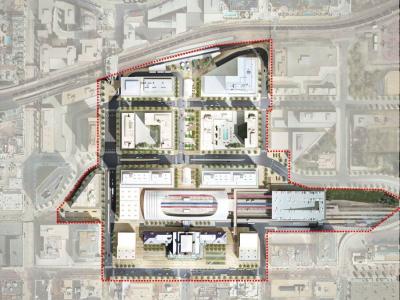

Figure 7. Denver Union Station project. 103

The project is a public-private partnership development venture located on approximately 50 acres in lower downtown Denver, Colorado, which includes the historic Denver Union Station building (excluding renovation of the building itself), rail lines, vacant parcels, street rights-of-way, and offsite trackage rights. The project comprises the redevelopment of the site as an intermodal transit district surrounded by transit-oriented development, including a mix of residential, retail, and office space. The transit district will serve as a regional multimodal hub connecting commuter rail, light rail and bus rapid transit, regularly scheduled bus service, and others, including:

Construction of light rail and commuter rail stations.

A regional bus facility.

Extension of the 16th Street Mall and the shuttle service.

Accommodation of the Downtown Circulator service.

Pedestrian improvements and improved street, replacement parking, and utility infrastructure.

Denver Union Station acts as a hub for all of Metro Denver's mass transit. The facility includes transportation options offered by the Regional Transportation District (RTD), the Colorado DOT, Greyhound, and Amtrak, and it connects intercity transit options to the Denver International Airport. By facilitating transit ridership, this project will reduce vehicle traffic and its accompanying emissions. Since the project's completion, the project area has added more than 200 stories of office, retail, residential, and hotel space.

Funding and financing sources included sales tax revenues, TIF, and an appropriation backstop from the City and County of Denver to improve the credit quality of debt. TIF provided repayment of $300 million in Federal loans, or approximately 60 percent of total project costs, which were approximately $500 million. The sale of government land (another form of value capture) provided an additional $38.4 million in revenue that was applied to the project.105

The project also received loans from two Federal credit programs: the Railroad Rehabilitation and Improvement Financing program and the Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (TIFIA) program. TIF revenues and property taxes were expected to cover debt service; however, sales taxes and the city-contingent commitment provided a backstop in the event that these revenues were insufficient.

TIF can benefit from a backstop support to improve credit quality.

TIF can work in tandem with traditional sources of funding, such as sales tax revenues.

BATIC Institute. Webinar: Denver Union Station Redevelopment Project, March 30, 2016. http://www.financingtransportation.org/capacity_building/event_details/webinar_dus.aspx.

Denver Union Station Project Authority. 2011, February 1. Plan of Finance Prepared for Federal Highway Administration. TIFIA Joint Program Office.

Federal Highway Administration. Project Profile: Denver Union Station. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ipd/project_profiles/co_union_station.aspx.

RTD website. https://www.rtd-denver.com/fastracks/union-station.

84 Vadali, Sharada, et al. 2018. Guidebook to Funding Transportation Through Land Value Return and Recycling. NCHRP Report 873. p. 35. http://www.trb.org/Main/Blurbs/177574.aspx.

85 Ibid. p. 65.

86 Ibid.

87 Ibid. p. 35.

88 Ibid. p. B-15.

89 Illinois Tollway. Illinois Route 53/120 Project Overview. https://www.illinoistollway.com/documents/20184/96146/IL_Route53_120_FactSheet_FINAL_081613.pdf/d704f34b-bdb2-4532-bb47-ec94c80f272c. Project was cancelled.

90 Vadali, Sharada, et al. Guidebook to Funding Transportation Through Land Value Return and Recycling. NCHRP Report 873. p. B-17. http://www.trb.org/Main/Blurbs/177574.aspx.

91 Illinois Route 53/120 Finance Committee. 2015, March. Illinois Route 53/120 Feasibility Analysis. p. 35. https://www.illinoistollway.com/documents/20184/96146/201503+53-120+finance+committee_final+report.pdf/9173fbe2-173a-47ee-85b5-1639f9221997?version=1.0&t=1462802607425.

92 The findings provided in NCHRP Report 873 were written in 2017 and were very upbeat. The findings presented here are the author's conclusions after reading the 2015 Financial Analysis and newspaper accounts of the evolution of the project.

93 Vadali, Sharada, et al. Guidebook to Funding Transportation Through Land Value Return and Recycling. NCHRP Report 873. p. B-17. http://www.trb.org/Main/Blurbs/177574.aspx.

94 Atlanta BeltLine. Atlanta BeltLine Tax Allocation District. https://beltline.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/ABI_TAD.pdf.

95 Federal Highway Administration. Project Profile: Atlanta BeltLine. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ipd/project_profiles/ga_atlanta_beltline.aspx.

96 Atlanta BeltLine. Affordable Housing on the BeltLine: Goals & Progress. https://beltline.org/the-project/affordable-housing-on-the-beltline/goals-progress/.

97 Atlanta BeltLine. 2013. Atlanta BeltLine 2030 Strategic Implementation Plan. Final Report. p. 32. https://beltline.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Beltline_Implementation-Plan_web.pdf.

98 Invest Atlanta. 2016, June 30. Beltline Tax Allocation District Fund: Financial Statements and Supplementary Information. https://www.investatlanta.com/assets/beltline_tad_2016_fincial_statements_jpv8LwM.pdf.

99 Atlanta BeltLine. The Project: Special Service District (SSD). https://beltline.org/the-project/special-service-district/.

100 Atlanta BeltLine. The Project: Project Funding & Financials. https://beltline.org/the-project/project-funding/.

101 Atlanta BeltLine. 2013. Atlanta BeltLine 2030 Strategic Implementation Plan. Final Report. pp. 46–47. https://beltline.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Beltline_Implementation-Plan_web.pdf.

102 Ibid.

103 USDOT. Denver Union Station Project. https://www.transportation.gov/buildamerica/projects/denver-union-station.

104 Ibid.

105 Vadali, Sharada, et al. Guidebook to Funding Transportation Through Land Value Return and Recycling. NCHRP Report 873. p. 53. http://www.trb.org/Main/Blurbs/177574.aspx.

106 Ibid. p. B-16.

107 Ibid.