The Atlanta BeltLine project highlights the use of tax increment financing (TIF), known in Georgia as a tax allocation district (TAD), for a multimodal project that includes roadway improvements, bike lanes, pedestrian paths, and transit, in addition to the development of green space and other amenities.

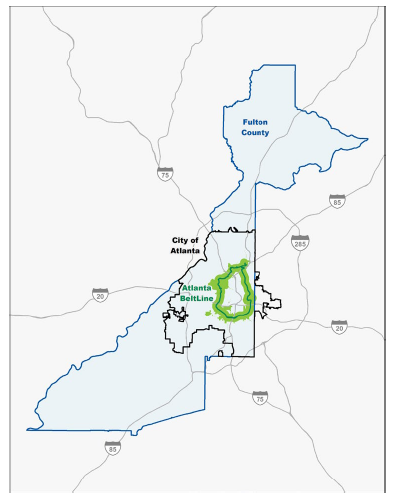

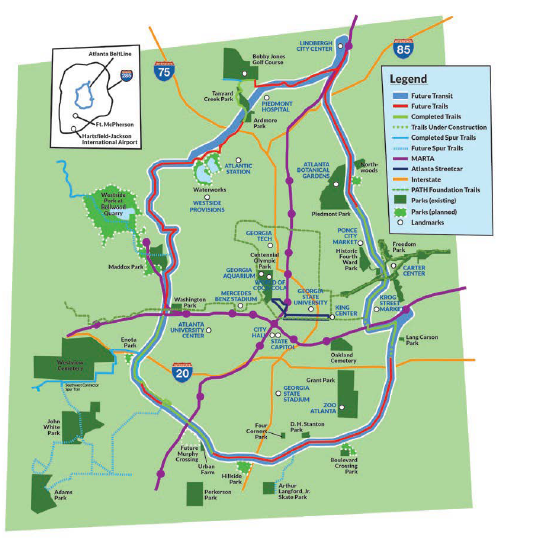

The Atlanta BeltLine is a planned 6,500-acre development that will loop around Downtown Atlanta. It is expected to spur an additional 15,000 acres in development beyond its immediate area. The project aims to connect 45 neighborhoods through 45 miles of streetscape alterations, 33 miles of trails, 22 miles of streetcars, and 2,000 acres of parks. It has been under construction since 2006, opening in phases in the years since. By 2030, all phases of the Atlanta BeltLine are expected to be complete. The Atlanta BeltLine loop is built on a historic 22-mile rail corridor, and the 15,000-acre planning area includes 22 percent of the city's population and 19 percent of its land area. 1

The objectives of Atlanta BeltLine are as follows:

The Atlanta BeltLine is considered to be successfully achieving many of these goals, although it is falling behind on affordable housing construction and faces other equity challenges. 4 5 Several of the goals above seek to address many of the challenges of Atlanta's public spaces and neighborhoods. For example, prior to the BeltLine's construction, the surrounding neighborhoods were distressed. From the perspective of greenspace, in the early 2000s, Atlanta was ranked 50th out of the Nation's 55 most populous cities in terms of parkland as a percentage of city area.

The Atlanta BeltLine concept was first conceived in 1999 as Georgia Tech graduate student Ryan Gravel's master's thesis. The idea quickly took off after gaining the interest of several citizen groups and Atlanta City Council President Cathy Woolard. 6 By 2005, the Atlanta BeltLine had moved from concept to construction, after receiving the approval of the city of Atlanta and several other government entities, as well as the backing of several private and nonprofit organizations.

Atlanta BeltLine Stakeholders

The creation and continued progress of Atlanta BeltLine is the result of coordination between several governmental organizations, non-profit organizations, and local businesses. Several organizations were already in existence prior to the planning of the BeltLine, while others were created for the purpose of carrying out the project. Table 1 and Table 2 briefly describe the roles of key parties involved in the development of the project.

| Stakeholder | Description of Role |

|---|---|

| City of Atlanta | The city of Atlanta, which is the future owner of all Atlanta BeltLine investments, participates in the Atlanta BeltLine TAD. It also appoints members to the Atlanta BeltLine, Inc. (ABI) and Atlanta BeltLine Affordable Housing Advisory boards. |

| Fulton County | Fulton County participates in the Atlanta BeltLine TAD. It makes appointments to the ABI board of directors and the Atlanta BeltLine Affordable Housing Advisory Board. |

| Atlanta Public Schools | Atlanta Public Schools is an Atlanta BeltLine TAD participant and appoints members to the ABI Board of Directors and the Atlanta BeltLine Affordable Housing Advisory Board. |

| Invest Atlanta | Invest Atlanta is the city's economic development agency. It is responsible for the creation and management of all Atlanta-based TADs. It is playing an active role in the affordable housing components of the project. |

| Atlanta BeltLine, Inc. (ABI) | ABI was formed by Invest Atlanta as a nonprofit organization to manage the Atlanta BeltLine program. The organization defines the program, seeks grants and other funding, facilitates community engagement, manages vendors, tracks progress and reports to government entities. |

| Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority (MARTA) | MARTA is the Atlanta transit agency that will develop intermodal linkages to the Atlanta BeltLine and be responsible for the development of the Atlanta BeltLine's transit components. |

| Georgia Department of Transportation (GDOT) | GDOT owns the ROW on the Atlanta BeltLine corridor and coordinates with ABI to manage the Atlanta BeltLine's ROW. GDOT also administers the Statewide Transportation Improvement Program, part of which funds the Atlanta BeltLine's design, ROW acquisition, and construction. |

| Atlanta Regional Commission | The Atlanta Regional Commission is a planning and intergovernmental coordination agency that has supported ABI's planning and assisted in securing State funds. |

| Tax Allocation District Advisory Committee (TADAC) | The Atlanta BeltLine TADAC was established by the city of Atlanta to make recommendations to ABI, Invest Atlanta, and the city on issuance, allocation, and distribution of TAD bond proceeds. The TADAC also measures the Atlanta BeltLine's impact and progress on implementation of its redevelopment plan. |

| BeltLine Affordable Housing Advisory Board | The BeltLine Affordable Housing Advisory Board advises on issues related to affordable housing, with members from Fulton County, the city of Atlanta, Atlanta Public Schools, community development corporations, and the real estate community. |

| Department of City Planning | The Atlanta Department of City Planning is responsible for the Atlanta BeltLine's planning area zoning. It separated the 16,000 acres within one-half mile of the rail corridor into 10 subareas for land use master plans, which encourage land uses that facilitate transit, parks, denser development, walking, and bicycling. |

| Stakeholder | Description of Role |

|---|---|

| Atlanta BeltLine Partnership | The Atlanta BeltLine Partnership is funded by the private sector. It was created to raise capital, awareness, and support for the project. The Atlanta BeltLine Partnership hosts guided tours, "adopt-a" programs, speakers, and other programming. |

| PATH Foundation | The PATH Foundation was created to enhance and preserve Georgia greenways. The organization works with ABI and the Atlanta BeltLine Partnership to develop the Atlanta BeltLine trail network, including coordinating the use of private funding. |

| Trust for Public Land | The Trust for Public Land helped evaluate the Atlanta BeltLine TAD's financial feasibility and purchased the parcels on which Atlanta BeltLine parks will be developed. |

| Trees Atlanta | Trees Atlanta is working with ABI to create an arboretum, plant trees, and remove certain species from the Atlanta BeltLine area. |

BeltLine Progress

Since its inception, the Atlanta BeltLine has visibly progressed, which has helped to strengthen its image and the commitment of policy makers and stakeholders to the project. As of mid-2019, $500 million in capital improvements had been made, mostly related to parks and trails. According to ABI, as of the end of 2018, $559 million in capital improvements had been invested in the Atlanta BeltLine project, spurring $4.6 billion in private redevelopment (an 8.5-to-1 return on investment). Figure 3 and Figure 4 highlight the dramatic transitions in the Atlanta BeltLine planning area.

Before: The Eastside Trail by Ponce City Market as an overgrown railroad corridor in 2008.

After: The Eastside Trail as an open multi-use trail with development, public art, an arboretum, and more.

Reproduced with permission from Atlanta BeltLine, Inc.

Before: Historic Fourth Ward Park and Ponce City Market in 2008.

After: Historic Fourth Ward Park during an Atlanta Symphony Orchestra performance in 2018.

Roadway Improvements

Some of the 45 miles of planned streetscape work will be completed as a component of transit construction and some, such as the Ponce de Leon improvements, are the result of coordination between multiple agencies and funding sources.

The Atlanta BeltLine, Inc. (ABI) 2005 Redevelopment Plan set out a vision for roadway improvements as a tool for increasing economic redevelopment in the Atlanta BeltLine's neighborhoods. ABI anticipates that some streetscape projects will be implemented as part of private developments and as part of transit implementation. 7 Additional streetscape improvements beyond those identified in the Redevelopment Plan will continue to be implemented as part of other Atlanta BeltLine projects. 8

In addition to streetscape improvements, a number of roadway projects to mitigate traffic impacts of redevelopment were identified as part of the Redevelopment Plan. These projects were further defined and additional projects were identified through the Subarea Master Planning process; many are located outside the Atlanta BeltLine TAD. 9

The Atlanta City Council approved the Atlanta BeltLine's 25-year financial plan in 2005, following a 12-3 vote, establishing the Atlanta BeltLine TAD. Shortly after, Atlanta Public Schools and the Fulton County Board of Commissioners voted to enter into an intergovernmental agreement with the city to share future tax revenues with the Atlanta BeltLine through the TAD. 10 Soon after its formation, the TAD faced a legal challenge from local attorney John Woodham, 11 who argued that participation by Atlanta Public Schools in the TAD violated the "Educational Purpose Clause" in the Georgia State Constitution, as it diverted funds that could be used for education to non-educational purposes. 12 The case pushed for the removal of Atlanta Public Schools from the agreement, a move that, if successful, would dramatically decrease the Atlanta BeltLine's primary funding source, reducing TAD revenues by 45 percent. 13

In 2008, due to the ABI lawsuit and the broader risk to other TADs in Georgia, the State held a referendum to change the constitution to allow TADs to use educational purpose revenue. The referendum narrowly passed with 51 percent of the vote, after which Georgia passed House bill 63, also known as the "Redevelopment Powers Law." The Redevelopment Powers Law explicitly allows TADs to use school district revenue to fund redevelopment projects. 14

As inactive rail corridor, the Atlanta BeltLine has utilized the "Rails to Trails" program to mitigate some of the real estate title risks commonly associated with purchasing rail corridor and converting it to a trail and transit system. 15

The Atlanta BeltLine revenue projections were based on a financial feasibility study estimating future growth in the value of properties in the 6,500-acre redevelopment area of the Atlanta BeltLine that comprises the TAD. Initial projections were completed in 2006 and based on historic property value increases. The TAD boundary was drawn in order to include key Atlanta BeltLine-driven redevelopment opportunities, avoid single-family neighborhoods, connect trails to nearby parks, and include major roadway corridors that would be improved in relation to the project. 16

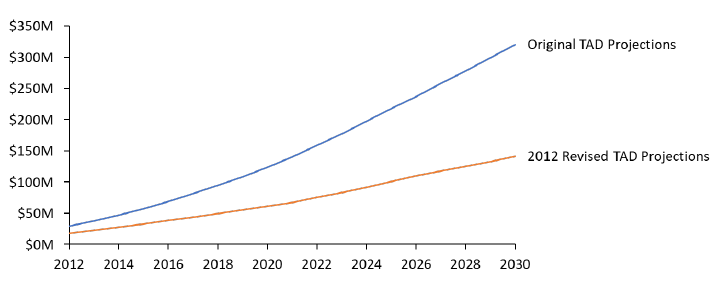

The ABI issued tax allocation district bonds based on the robust growth projections included in its initial feasibility study. However, the 2007-2009 recession led to a major slowdown in the growth of property values in the Atlanta BeltLine TAD area, such that these projections required a downward revision (see Figure 7).

Initial Funding Plan

The growth in property tax revenues within the 6,500 acres that comprise the Atlanta BeltLine TAD is to be directed to capital expenditures for parks, trails, and transit. 17 These revenues can be spent as they are collected or used to secure financing.

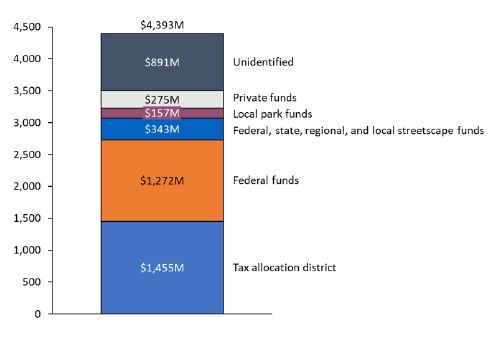

Property values were estimated to rise by $20 billion between 2006 and 2030, and of this growth, the TAD was originally projected to collect $3 billion in revenue for the BeltLine, or 66 percent of the project's $4.4 billion in required investments. The balance was expected to come from Federal, State, local, and private philanthropic funds.

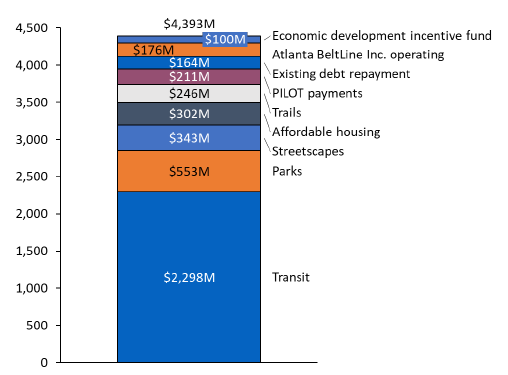

Funding for the Atlanta BeltLine is expected to be used for a number of purposes, based on the relative flexibility of the TAD guidelines. The uses of the $4.4 billion are illustrated in Figure 5 and Figure 6.

Transit investments account for about half of the costs, with spending on parks, streetscapes, affordable housing, and trails taking significant shares.

Breakdown of Atlanta Beltline funds, totaling $4,393 million. with nearly half spent on transit, $553 million on parks, $343 million on streetscapes, $302 million on affordable housing, more than $200 million on Trails and PILOT payments, and more than $100 million on existing debt repayment, Atlanta Beltline, Inc. operating, and economic development incentive fund.

Nearly half of the $4,393 million funding comes from the tax allocation district, $1,272 million from federal funds, $343 million from Federal, State, regional and local streetscape funds, $157 million from local park funds, $275 million from private funds, and $891 million from unidentified sources.

Shifts in Funding Plan

As a consequence of the 2007-2009 recession and a lawsuit that paused Atlanta Public Schools' revenue contribution, funding from the TAD was halved, as illustrated in Figure 7.

Despite this decline in revenue, the Atlanta BeltLine's initial program and projected costs have remained at $4.4 billion, requiring it to seek other funding sources and delay some projects. As of mid-2019, an estimated $900 million in funding had yet to be identified.

Furthermore, the ABI's revenue shortfall resulted in amendments to the agreement between it and the Atlanta Public Schools - two in 2009 and one in 2016. The process that led to these amendments is described in the next section Coordination and Partnership.

As TAD legislation was passed in 2009 after years of legal wrangling, the 2007-2009 recession was at its worst and the ABI struggled to pay its payments in lieu of taxes (PILOTs) to Atlanta Public Schools and make the investments to complete its master plan. In 2012, the city of Atlanta stepped in on behalf of ABI to renegotiate the PILOT payment with Atlanta Public Schools, which was eventually paid several months late.

In December 2013, the city communicated that the Atlanta BeltLine TAD would be unable to make the next payment. Atlanta Public Schools was unwilling to accept a lower PILOT payment as it was struggling with its own financial problems. The city and Atlanta Public Schools held meetings throughout 2014 and 2015 to resolve the issue, and in early 2016, they signed a third amendment. The city agreed to become current on payments through 2015, use funds from the sale of a civic center to make additional payments, and transfer property owned by the Atlanta Housing Authority to the school system for educational purposes. In turn, the PILOT payments to Atlanta Public Schools were lowered to $100.8 million from $174.9 million, a 42-percent reduction. 21

1 Owens, "The Atlanta BeltLine."

2 Atlanta BeltLine Redevelopment Plan, report prepared for the Atlanta Development Authority, November 2005, http://beltlineorg.wpengine.netdna-cdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/Atlanta-BeltLine-Redevelopment-Plan.pdf.

3 Atlanta BeltLine, Inc., Atlanta BeltLine 2030 Strategic Implementation Plan: Final Report, December 2013, http://issuu.com/atlantabeltline/docs/beltline_implementation_plan_web.

4 Nedra Rhone, "Can the Atlanta Beltline Improve Its Image?" The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, April 30, 2018.

5 "Affordable Housing," Atlanta BeltLine, Inc., 2019, https://beltline.org/category/programs/affordable-housing-programs/.

6 "Project History," Atlanta BeltLine, Inc., 2018, .

7 Atlanta BeltLine, Inc., Atlanta BeltLine 2030 Strategic Implementation Plan: Final Report.

8 Atlanta BeltLine, Inc., Atlanta BeltLine 2030 Strategic Implementation Plan: Final Report.

9 Atlanta BeltLine, Inc., Atlanta BeltLine 2030 Strategic Implementation Plan: Final Report.

10 "How the Atlanta BeltLine is Funded," Atlanta BeltLine, Inc.,2018, https://beltline.org/about/the-atlanta-beltline-project/funding/.

11 Woodham v. City of Atlanta, 657 S.E.2d (Ga. 2008).

12 Alyson M. Harter, "Update on Tax Allocation Districts (TADs) and the BeltLine Project," Williams Mullen, October 1, 2008, https://www.williamsmullen.com/news/update-tax-allocation-districts-tads-and-beltline-project.

13 Dan McRae, "Quick Takes: TADs - What to Do After the BeltLine Case," Seyforth Shaw Attorneys LLP, February 21, 2008, https://www.danmcrae.com/quicktakes/qt_08-feb21.pdf.

14 Molly Bloom, "After Years of Conflict, Mayor Kasim Reed and APS Reach Beltline Deal," The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, January 29, 2016, https://www.ajc.com/news/local-govt--politics/after-years-conflict-mayor-kasim-reed-and-aps-reach-beltline-deal/Wm6CxnlSwUmsVu78pcNsaK/.

15 "Rails to Trails," Surface Transportation Board, Public Information Resources, https://www.stb.gov/stb/public/resources_railstrails.html.

16 City of Atlanta, Georgia, The BeltLine, http://www.atlantaga.gov/Home/ShowDocument?id=1628.

17 "We're Developing a New Future for Atlanta!" Atlanta BeltLine, Inc., 2018, .

18 Atlanta BeltLine, Inc., Atlanta BeltLine 2030 Strategic Implementation Plan: Final Report.

19 Atlanta BeltLine, Inc., Atlanta BeltLine 2030 Strategic Implementation Plan: Final Report.

20 Atlanta BeltLine, Inc., "How the Atlanta BeltLine is Funded."

21 "City, APS Finally Settle 3-Year Feud Over Beltline TAD Payments," Buckhead View, January 31, 2016.