Bozeman, MT's impact fees program highlights how impact fees can be used to finance a significant share of capital investments in roads, bike lanes, and pedestrian facilities, as well as other classes of infrastructure.

The city of Bozeman, MT, in Gallatin County, is Montana's third-most populous city, with a population of about 45,000. It is well situated, given its relative closeness to two national tourist attractions, Big Sky Resort and Yellowstone National Park, and it is home to Montana State University and its 16,000 students. Bozeman has grown rapidly over the last two decades, and it is consistently ranked as one of the fastest-growing micropolitan cities in the United States as well as one of the strongest economies of its size.

Bozeman's population growth accelerated in the 1990s. After increasing by only 5 percent between 1980 and 1990, it grew by 20 percent during that decade. Its population also grew by 32 percent in the 2000s, with its housing stock increasing by over 50 percent during that time. Bozeman is projected to grow by another 33 percent in the 2010s. The city's rapid growth drove it to annex several thousand acres of land, and it currently covers 12,900 acres - 80 percent more than in 1996. 1 Details of Bozeman's population growth can be found in Table 1.

| Year | 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2020 (Projected) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 22,827 | 27,555 | 28,210 | 34,983 | 37,326 | 43,399 | 50,000 |

By the 1990s, Bozeman's growth started to strain its resources. To address its growing pains, city leadership implemented impact fees in March 1996 to fund additional infrastructure. Impact fees were charged to new developments in Bozeman to pay for the capital aspects of key services, specifically the additional road, sewer, water, and fire/emergency medical service needs that the construction of these new developments would drive. Bozeman policymakers took the view that new users were the drivers of increased capital needs, rather than existing users, and therefore impact fees were a much fairer way to pay for this construction than increased property taxes on existing developments. Any new home or business that connects to water or sewer services or contracts with the city for fire protection must pay impact fees. Bozeman still levies property taxes, but they primarily cover basic municipal services and operations.

Impact fees in Bozeman are set based on formal studies estimating the cost of growth over time and assigning a proportionate share of this cost to new construction. The amount of impact fees is dependent on key development attributes, such as whether the development is commercial, residential, or industrial; the size of the development; and other characteristics such as the development's number of bathrooms, parking lot size, and greenspaces. The city reviews the level of impact fees every 3-5 years.

When impact fees were first established, Bozeman's authority to charge them was unclear under the Montana State Constitution. The city had started studying impact fees a decade prior to implementing them when it hired a private attorney to study their legality, along with a team of city and county lawyers. Despite the city's significant legal preparation in advance of launching its impact fee program, it faced challenges almost immediately from the inception of the program. In December 1996, less than a year after impact fees were launched, the executive director of the Business and Consumers Bureau of Montana, Inc., requested an official legal opinion on the program from Montana's attorney general. He pointed to language in Montana's constitution stating that cities do not have self-governing powers, but "only those powers expressly given them by legislature." 3 The city, on the other hand, believed that given its express jurisdiction over services such as fire, water, and streets, it also had the right to raise money for these services. This dispute between the city of Bozeman and developer advocates continued for several years. It is outlined further in the Coordination and Partnership section of this case study.

In 2005, the Montana State House and Senate passed Senate bill (SB) 185, which gave Bozeman and other municipalities the clear authority to impose impact fees. SB 185 was a compromise bill that also included some safeguards developers had sought in order to limit the scope of these fees. For example, SB 185 established limits around the use of impact fees, disallowing their use to pay for services and requiring they be used for capital improvements. SB 185 also restricted the collection of impact fees to five types of public facilities: water supplies, sewers, transportation, stormwater, and emergency services, the latter of which included police, emergency medical services, and fire protection. Any impact fees beyond these five categories must be approved by a two-thirds city council vote. Finally, the law established advisory committees to review how impact fee funds are spent. 4

Impact fees have facilitated the improvement of Bozeman's infrastructure as it has continued to expand in population and size. To accommodate these ongoing changes and determine the impact fee levels that approximate the cost of providing new infrastructure, the city regularly hires consultants to conduct market studies on its impact fees. The studies gauge how population expansion and certain types of developments, such as retail, restaurants, and industrial, will affect traffic and in turn affect road needs, based on person-miles added to the system. Bozeman then calculated how many city roads and State roads will need be built according to the city's transportation master plan, at a cost of $3.3 million per lane-mile, and determined how to allocate these newly needed roads across new developments. Each person-mile of travel has been estimated to have a cost of $319. Bozeman also began calculating and allocating bicycle and pedestrian miles created from new developments and included new bike lane and sidewalk construction as part of a more holistic transportation impact fee. 5

Through this process, Bozeman was able to calculate the maximum allowable impact fee for each new development. This maximum allowable impact fee has increased with each study as costs and city needs have increased. The city council decides what percentage of the maximum allowable impact fee to charge. Bozeman has raised these fees several times, with street impact fees increasing to 60 percent of the maximum allowed in 2008. This increase caused fees for a 1,500- to 2,499-square-foot single family home to rise from $2,380 to $3,238. Those for a bank nearly doubled, from $10,470 to $19,024 per 1,000 square feet. Industry advocates viewed impact fees as harmful on the housing market, especially as the economy was struggling. For example, a 2007 study by the National Association of Home Builders concluded that every $819 charged at the time of construction would add $1,000 to the final price of a home. 6 Nonetheless, Bozeman went ahead due to significant needs to fund new infrastructure. After implementation, the city still expected to be short $7.4 million over 5 years for capital improvement program street projects. 7 Between 2011 and 2012, Bozeman considered cutting street impact fees by one-third to stimulate sluggish home building in the aftermath of the 2007-2009 recession. However, a reduction in impact fees would have required the city to raise property taxes to cover the growth-induced costs, which many residents and politicians in the region would consider an unfair distribution of responsibility. The proposal was not implemented. 8 The housing market quickly recovered, and in 2013 Bozeman voted to charge the maximum allowable street impact fees. 9

As discussed previously, Bozeman's impact fees cover road and other transportation infrastructure capital expansions and major renovations that can be attributed to growth, while property taxes cover operations and basic services. For instance, of the $33 million in street construction estimated as required between 2015 and 2020, $25.4 million or 77 percent, was projected to come from impact fees. 10

In order to avoid increasing property taxes to pay for its remaining capital needs, in 2015 Bozeman established an "Arterial and Collector Special Assessment." The city expects to fund the remainder of its $7.9 million in roadway capital needs from this assessment on all property owners within the Bozeman city limits. 11 , 12 The city's arterial and collector fund also included significant monies from owner or developer payback agreements, Federal and State grants, reimbursements, and other sources.

Impact fees pay for a much larger share of Bozeman's streets' capital costs than in Montana's larger cities, in part because its small size precluded access to State funds. 13

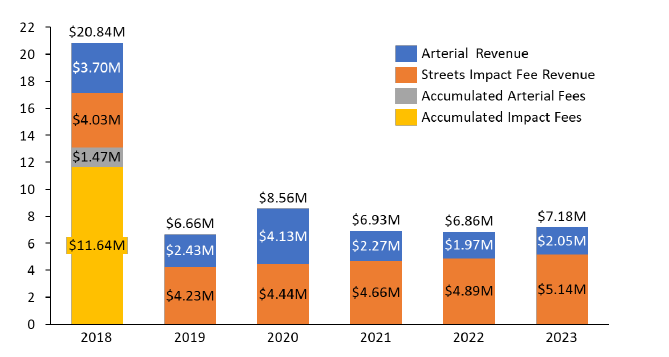

The impact fees calculated in Bozeman's most recent draft study (conducted in May 2018) would, when adopted, generate an average of $3.5 million to $5.0 million per year through 2040, or a total of $80 million to $115 million over the next 23 years. 14 The city's capital improvement plan for fiscal years 2018-2023 accounts for about $57 million in total improvements, utilizing accumulated funds from past years and projected impact fee and arterial revenue during that period. About 70 percent of this capital funding is expected to come from road impact fees, with arterial revenue funding the balance. The revenue breakdown is shown in Figure 1.

2023 includes arterial revenue, streets impact fee revenue, accumulated arterial fees, and accumulated impact fees.

Legal Challenges to Impact Fees

From the first year impact fees were implemented, Bozeman faced legal challenges, and for more than two decades, developer groups have continued to push back against them. A timeline of these disputes is as follows:

Throughout this process, citizen activists, who had significant influence in Bozeman given its culture and small size, supported the impact fee. While developers on the other side of this argument were highly influential and well-resourced, the citizen activists made very vocal arguments that helped explain the benefits of the policy to residents, preventing developers from solely shaping the impact fee debate. 17

Impact Fee Effects on Developers and Attempts to Mitigate

Although impact fees enjoyed broad support, even sympathetic citizens and council members were concerned that they could harm the city's economy. As Bozeman sought to woo several national commercial chains, it found that many of its efforts failed or came close to failure. Citing impact fees, Kohl's threatened to scrap its plans for a new Bozeman store, although it ultimately relented. Meanwhile, Qdoba and Best Buy scoped Bozeman for potential locations, but both chose not to open sites in the city, with Qdoba choosing to locate 2 hours away in Billings, MT, instead. While it is unclear whether impact fees were the true motivation behind these stores' decisions, it is clear that Bozeman had higher fees than other cities in Gallatin County, other Montana cities, and other regional hubs such as Boise, ID, and Spokane, WA. 18

Bozeman made several tweaks to its impact fees, mindful of the business community's concerns. For example, when Bozeman increased road impact fees to 60 percent in 2008 during a period when the city's retail market was especially sluggish, it included special incentives for retail spaces so that street impact fees dropped from $6,672 to $5,599. 19 In 2013, by unanimous vote, Bozeman also began permitting developers to defer payment of street impact fees until a structure was ready to be occupied, rather than when construction began, in line with an argument that developers had made at least since 1997. To reduce the risk of nonpayment if this option were exercised, the impact fee deferral process required a $50 application fee, a lien against the property, a $1,000 penalty, interest, and responsibility for the city's legal costs if fees were not paid on time. 20

1 Bozeman Transportation Master Plan, prepared by Robert Peccia & Associates and Alta Planning + Design for the city of Bozeman, Montana, April 25, 2017, https://mdt.mt.gov/publications/docs/brochures/bozeman_tranplan_study.pdf.

2 "Google Public Data," Google, September 18, 2018, https://www.google.com/publicdata/directory.

3 Gain Shontzler, "Attorney General Declines Request for Impact Fee Opinion," Bozeman Daily Chronicle, December 9, 1996, https://www.bozemandailychronicle.com/attorney-general-declines-request-for-impact-fee-opinion/article_3b0c3487-7fed-5858-87a4-4e7347888a2d.html.

4 Walt Williams, "County May Study Impact Fees," Bozeman Daily Chronicle, December 7, 2005, https://www.bozemandailychronicle.com/news/county-may-study-impact-fees/article_245282f4-1655-5e76-837c-91b5ca96d37b.html.

5 City of Bozeman Transportation Impact Fee Update Study, prepared by Tindale Oliver Consulting for the city of Bozeman, Montana, 2018, https://www.bozeman.net/Home/ShowDocument?id=6942.

6 Amanda Ricker, "City to Consider Tripling Fire Impact Fees," Bozeman Daily Chronicle, June 21, 2008, https://www.bozemandailychronicle.com/news/city-to-consider-triplingfire-impact-fees/article_91600ade-6499-512a-9e81-83c9ba0952a7.html.

7 Amanda Ricker, "City Vote Upholds Impact Fee Increase," Bozeman Daily Chronicle, January 14, 2008, https://www.bozemandailychronicle.com/news/city-vote-upholds-impact-fee-increase/article_25870262-9a2f-5191-991e-595289f74707.html.

8 Amanda Ricker, "Bozeman to Consider Cutting Street Impact Fees Monday," Bozeman Daily Chronicle, October 23, 2011, https://www.bozemandailychronicle.com/news/city/bozeman-to-consider-cutting-street-impact-feesmonday/article_38845172-fd3b-11e0-b4d8-001cc4c03286.html.

9 Amanda Ricker, "Bozeman Votes to Charge Full Amount for Street Impact Fees." Bozeman Daily Chronicle, February 5, 2013, https://www.bozemandailychronicle.com/news/city/bozeman-votes-to-charge-full-amount-for-street-impactfees/article_f002ba3c-6fae-11e2-9c48-001a4bcf887a.html.

10 City of Bozeman, Montana, City Manager's Recommended Budget for Fiscal Year 2016, May 11, 2015, https://www.bozeman.net/home/showdocument?id=3731.

11 "Arterial and Collector Street Special Assessment," Bozeman, Montana, https://www.bozeman.net/departments/finance/special-assessments/arterial-and-collector-street-special-assessment

12 Eric Dietrich, "Building Industry to Audit Bozeman Impact Fee Program," Bozeman Daily Chronicle, December 16, 2015

13 Amanda Ricker, "Chamber, Developers Say Impact Fees Driving Businesses Away from Bozeman, But City Says It Would Have to Raise Taxes Without the Fees," Bozeman Daily Chronicle, July 31, 2011, https://www.bozemandailychronicle.com/news/chamber-developers-say-impact-fees-driving-businesses-away-from-bozeman/article_903b4002-bafa-11e0-9e91-001cc4c002e0.html.

14 Tindale Oliver Consulting, City of Bozeman Transportation Impact Fee Update Study.

15 Al Knauber, "Developers Fight Impact Fees," Bozeman Daily Chronicle, March 30, 1997, https://www.bozemandailychronicle.com/developers-fight-impact-fees/article_5a79d055-efd8-577a-97a0-743eda547da5.html.

16 Eric Dietrich, "SWMBIA Again Suing Bozeman Over City Impact Fees," Bozeman Daily Chronicle, June 15, 2017, https://www.bozemandailychronicle.com/news/city/swmbia-again-suing-bozeman-over-city-impactfees/article_d8bca7ae-d777-54d5-8ef9-13e97e462dc5.html.

17 Steven Kirchhoff, former Bozeman mayor, Interview, December 5, 2018.

18 Ricker, "Chamber, Developers Say Impact Fees Driving Businesses Away from Bozeman."

19 Ricker, "City Vote Upholds Impact Fee Increase."

20 Amanda Ricker, "Bozeman Builders Will Be Allowed to Defer Impact Fees," Bozeman Daily Chronicle, April 2, 2013, https://www.bozemandailychronicle.com/news/city/bozeman-builders-will-be-allowed-to-defer-impactfees/article_af8b45d6-9b47-11e2-9bcd-001a4bcf887a.html.