U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

Erica Interrante

FHWA Office of Policy Transportation Studies

PDF Version 2.8MB

This report presents a summary of findings from research by the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) on trends related to the travel behavior of youth (ages 15–26). Its objective is to provide answers to questions about youth travel trends and identify factors that significantly affect their travel decisions and are shaping the way they travel.

The efforts of the FHWA’s Next Generation of Travel project have been to examine the effects of these hypotheses in the context of rises and falls in Person Miles Traveled (PMT), trip making and mode selection, as well as to develop a better understanding of how views on car ownership, other modes of travel, the environment and technology affect youth travel. Our findings are based on several qualitative and quantitative research efforts, including a review of current literature, nationwide focus groups, and a statistical analysis, which includes the development of a set of multivariate models to assess factors that influence travel among younger populations. Data from the National Personal Transportation Survey (NPTS, 1990) and the National Household Travel Surveys (NHTS, 2001 and 2009) were used in this analysis.

Total Annual Person Miles Traveled (PMT) Per Age Group, By Transportation Survey Year

Source: NPTS, NHTS Data Program 1995, 2001, 2009

It is well-known that on a national scale, there has been a significant drop in both vehicle miles traveled (VMT) and person miles traveled (PMT) in the past decade. Total PMT, which includes vehicle travel, has dropped most significantly among younger populations (ages 21–30), as shown in the graph above.

Our research reveals that, compared with previous generations, youth travel has decreased. They are driving less, making fewer trips and traveling shorter distances. Younger commuters also appear to drive alone to work more frequently then similarly-aged workers from previous generations. Understanding these changes has policy implications for the future of transportation when considering how to best finance the system while continuing to make it affordable for the average user, as as well as determine traveler needs based on mode shifts and an increase desire for multimodal systems and/or vehicles that are fuel efficient.

Relative to these declines, there has been considerable research in the field of travel behavior and travel demand to explain what is occurring nationally and among younger populations. Explanations that have been presented concerning these changes include the following:

The following report summarizes and highlights the most significant outcomes our research, in context of these explanations and to the degree of which they may influence travel decisions.

Figure 2: Annual Household Income and Trip-Making (2009)

Source: NPTS, NHTS Data Program 1995, 2001, 2009

Economic factors, such as employment status and household income, strongly influence the travel of both youth and adults. Economic factors are statistically shown to be highly correlated with PMT and trip making. They are also a consistent predictor of commute mode choice.

The youth of today have been greatly impacted by the Recession (2009). A recent Pew Center survey (2010) reported that thirty-seven percent of young respondents (ages 18-29) were either out of work or underemployed, the highest in three decades.[1] Unemployment not only affects work travel, but limits resources for travel for other purposes, such as shopping or recreation.

Youth are making choices about their travel that are being influenced by the constraints of their personal income. These choices may include foregoing vehicle ownership, driving less, taking more public transit, and possibly choosing to live areas with shorter trip distances and access to other modes of travel. Because of their financial situation, many may still be living at home with parents and are dependent on the family vehicle.

Figure 3: Unemployment Rates by Age Group (1910-2009)

Youth who are living on their own, in addition to their housing expenses, are also likely to have a substantial amount of student loan debt. Although the economy may be dampening their ability to own a vehicle, many may chose to eventually purchase a car once they are more settled in life with a family and a career.

Although travel related to geographic location was not the focus of this study, feedback from focus group participants suggested that geographic location, coupled with finances played the greatest role in whether or not youth owned a vehicle. Youth who lived in more car dependent areas viewed a car as a necessity versus those who lived in areas with robust transit service.

The effect of geography

on PMT and mode choice is

well-documented in research. Population density and living in New York City is positively

correlated with transit use. Population density is also negatively correlated with

PMT, which may be due to urban area characteristics that discourage car travel,

such as shorter trip distances to work and places of interest, congestion and

lack of parking, and the availability and use of other modes of transportation.

The effect of geography

on PMT and mode choice is

well-documented in research. Population density and living in New York City is positively

correlated with transit use. Population density is also negatively correlated with

PMT, which may be due to urban area characteristics that discourage car travel,

such as shorter trip distances to work and places of interest, congestion and

lack of parking, and the availability and use of other modes of transportation.

Current national housing trends have shown that younger populations, although less settled than older populations, prefer to live in urban areas. As young people continue to gravitate towards urban areas, they will become accustomed to living in places that offer a variety of travel options.

The Internet and mobile technologies have enabled people to access information from almost any location, increasing mobility and changing the way we work, socialize and travel. Research is inconclusive on whether the use of ICT increases or substitutes for travel. Studies have shown that individuals use technology in different ways; some use technology to consolidate trips and others use it to reach activity opportunities that require longer travel times.

Figure 4: Use of Technology by Age (2001, 2009)

Source: NPTS, NHTS Data Program 1995, 2001, 2009

Today’s youth are especially noted for their frequent use of web-based technologies, which raises questions to whether this affects the time they spend traveling and/or substitutes for trips that could be made in person. For instance, are their shopping trips being replaced by online purchases? And do their reliance on mobile phones and other devices reduce their willingness to drive and/or increase their preferences for being transported?

Statistically, our research has shown that there is little correlation between technology use (i.e. measured as the number of times a person uses the Internet) and reductions in travel. In fact, in one survey year, web use is associated with increases in travel. Questions still exist as to whether this is an effect of income, as Internet use is positively correlated with education and income, or does a person’s increased access to information encourage them to engage in more activities and/or possibly make traveling more efficient?

Most youth participants in the focus groups viewed their mobile phones and use of the Internet as significantly improving their day-to-day activities and travel experiences through saved time and added convenience. They did not see social media tools and online communication platforms replacing their in-person socializing with friends (who lived in the general vicinity), but rather as a way to keep connected with their friends and family on an immediate basis.

As we look ahead, how might current trends concerning youth affect the future of personal travel? Given the effects of the most recent Recession and past economic trends, we may say that personal income will continue to remain a leading influencer in total travel. Car ownership decisions will also continue to be economically-driven.

As continued urbanization creates the need for greater travel options, the next generation of travelers may become less reliant on their cars and more accustomed to using other modes of travel. Environmental concerns may also have an impact on car buying and travel decisions.

The growing availability and use of travel information, made possible by advancements in ICTs, is increasing the public’s familiarity with the transportation system and their ability to make informed travel decisions, possibly encouraging growth in travel through increased efficiencies.

The following full report details these and other factors that may be influencing the travel decisions of youth, and presents information for further discussion on emerging issues related to travel demand, transportation policy, and the needs and perspectives of those who are soon to be the most predominate users of the transportation system.

We would like to recognize and thank the following people for their contributions to this project including, Michael Lawrence, Lewison Lem, Janine Mans, Judy Mueller, Rami Chami and Devon Cartwright Smith from Jack Faucett and Associates for their coordination of research activities related to the project, technology scan and scenario development; the research team from the University of California- Los Angeles Institute of Transportation Studies, including Evelyn Blumenberg, Brian Taylor, Michael Smart, Kelcie Ralph, Madeline Wander and Stephen Brumbaugh for their work on the statistical analysis and Maddy Wolf from Premium Solutions for her work with the focus groups.

From FHWA, we would like to recognize and thank the following people for their work on this project, including those who reviewed and provided feedback on the materials, Office of Policy-Transportation Studies (HPTS) Director Mary Lynn Tischer, Adella Santos (HPPI), Gabe Rousseau (HEPH), Diane Turchetta (HEPN) and James Pol (RITA); Alan Adon for his work on the cover design; Cynthia Hatley for her contributing research on the generations, and for overall project management and report writing, Heather Rose (HPTS) and Erica Interrante (HPTS).

CHAPTER ONE: Background—Factors that Influence Travel

CHAPTER TWO: Profile of Generation Y—The Millennials

CHAPTER THREE: Youth and Travel—What is Happening and Why?

This study explores factors that influence the travel behavior of youth and their impact over time. The youth of today have shown to be traveling less. Is this a result of the latest recession, which has notably impacted younger generations, or are youth changing their travel preferences for other reasons? And what role is the use of new technologies for communicating and accessing information among the generation who grew up with the Internet playing in their travel decisions? This is the focus of this report.

The work completed under FHWA’s The Next Generation of Travel project provides for both a quantitative and qualitative evaluation of current and emerging travel shifts among the different generations, with a focus on youth ages 16-27. The quantitative portion of this project is the statistical analysis conducted by the University of California-Los Angeles (Blumenberg et. al.), using primarily National Household Travel Survey (NHTS) data to analyze differences across age cohorts and generations over time and to identify any new or emerging predictors of travel that fall outside the traditional norms as a person ages from youth to retirement. In addition to the statistical analysis, several focus groups were held across the country to further explore the results of the statistical analysis and generational perceptions on transportation-related issues.

In conjunction with both the statistical analysis and focus groups, in-depth literature reviews were written on both current sociological issues and their effect on travel behavior, and emerging transportation technologies, with an emphasis on how future generations will interface with these technologies in the areas of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT), Global Positioning Systems (GPS), Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS), electronic payment systems and fuel efficient vehicles.

This report summarizes the information and findings from this research. Its purpose is to identify trends that are influencing the travel decisions of youth and speculate how these trends may impact future travel forecasts. It may also be used to help guide future research and policy initiatives related to personal travel.

The study of travel demand has been relatively consistent in identifying factors that typically have an effect on personal travel. These factors include traveler characteristics, such as a person’s age, income, worker status, number of vehicles owned, how far he/she travels to frequent points of destinations and for what purpose. These factors are commonly measured through rises and fall in VMT (vehicle miles traveled), PMT (person-miles traveled) and number of trips, as well as changes in travel related to mode choice, trip purpose and length.

On a broader scale, social, economic and technological influences also affect personal travel, but in ways that are difficult to measure given their interrelatedness to traveler characteristics, such as the impact of the economy on personal income, which affects a person’s decision not to own a vehicle. The following information provides brief explanations of how factors that influence travel are affected over time, through three overlapping processes—life cycle effects, period effects and cohort effects.

Figure 5: VMT by Age and Income

Life cycle effects can be defined as the characteristics or events that occur during a person's life that create a change in one's lifestyle. Life cycle effects considered most often in travel behavior-related studies include age, income, whether children are present in the household, household size, worker status and vehicle ownership. Of all the life cycle effects identified, age and income have the greatest impact on how much a person travels. Research has shown that over time the amount of vehicle miles people travel peaks around mid life and then gradually decreases as they age, most likely due to health issues that impede driving as a person ages, such as poor vision.

Income is also a strong indicator of how much a person travels. Historical trends have shown that as real personal incomes have risen, so has vehicle miles traveled (VMT).

Higher incomes contribute to increased car ownership and expenditures on transportation and can influence the length and number of trips people take as they may commute longer distances and/or take more discretionary trips.

Period effects are social movements, economic downturns, major events, medical, scientific, or technological breakthroughs that affect all age groups on a large scale and simultaneously, but the degree of impact may differ according to where people are in their life cycle.

The economy plays a significant role in increases and decreases in VMT because of its effect on gas prices, employment, personal income and the household budget. In the short term, rises in the price of gas have contributed to drops in VMT, which has occurred during times of past economic recessions.

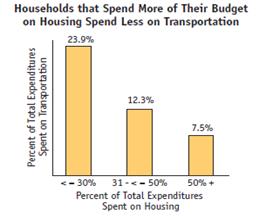

Source: Center of Neighborhood Technology calculation using data from 2002 Consumer Expenditure Survey

As people lose their jobs and/or their income becomes reduced or stagnates during a recession, they adjust their household budget to meet the demands of rising transportation costs. In addition to fuel, insurance, vehicle repair and maintenance expenses, other factors that affect household transportation costs include the number of miles someone needs to travel, the number of wage earners per household, location, vehicle fuel efficiency and the costs for bus and rail services. Often there is a tradeoff between what a household spends on housing vs. transportation (i.e. if more is spent on housing, then less is spent on transportation and vice versa)[2]

In addition, high unemployment reduces the number of people driving to work, and reduced consumer spending results in fewer shopping trips and freight shipments. Although these declines may not have a lasting effect, they show how sensitive changes in VMT are to changes in the economy.

Policies and programs affect personal travel behavior. In the past 10 to 15 years, regulatory initiatives from the public sector have made the process for obtaining a driver's license more difficult through graduated licensing regimes. In addition, due to budget constraints, many school systems that once offered driver's education as part of the high school curriculum have eliminated the program, shifting the cost of driver's education from the state to parents. Today, only 15 percent of students are enrolled in driver's education through their schools. Additionally, student and employer subsidies in urban areas and other public subsidies for public transportation use may encourage a shift to other modes.

Social trends and movements over time have affected personal travel in a variety of ways; for instance, women entering the workforce over the past 40 years has added to the number of vehicle trips, and an increase in trip chaining, as women often combine their commute with transporting children and other household responsibilities. This change has resulted in a permanent shift in travel demand and increased vehicle ownership per household.

Large-scale catastrophes and tragic events may also lead to changes in public opinion that could affect travel; for instance, incidents like the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf Coast in April 2010, remembered as the largest marine oil spill in petroleum industry history, raised the public's environmental awareness. A poll conducted through the Pew Center in June 2010, reported that sixty-five percent of young people surveyed said that the highest goal of U.S. policy should be protecting the environment.

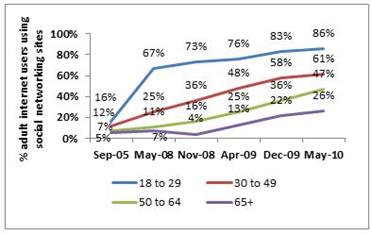

Technological breakthroughs and market-wide adoption of products in the realm of Information Communication Technologies (ICT) have changed the way people interact with one another. Nearly all of U.S. zip codes have some level of broadband access, further making high-speed Internet available to a majority of households in the U.S. Younger generations are especially noted for their frequent use of online platforms and social networking sites.

The Internet and mobile technologies have enabled people to access information from almost any location, increasing mobility and changing the way we work, socialize and travel. Mobile phone applications that provide travel information have enabled people to become more efficient travelers. With these technologies, people can map out routes instantly, avoid congestion, find parking, pay for a transit trip, arrange for carpooling and locate a vehicle, if using a car sharing service. Web-based technologies have also enabled more people to work from home.

Figure 7: Paradigm Applied to an Online Purchase

Substitution (negative): Travel decreased An online purchase replaces the physical trip a person makes to a brick and mortar store. |

Complementarity (positive): Travel increased An online purchase creates a physical trip to a store related to the online purchase (e.g. batteries for a new toy) or other information acquired online. |

Neutrality: No effect An online purchase is independent of a shopping trip and has no effect on travel. |

Modification: Travel shifts An online purchase may reduce a shopping trip, but may create a trip associated with the delivery of a package. It may also change the characteristics of a shopping trip, such as timing and chaining. |

Technology use may also change how people use their time and, therefore, how much they travel and for what purpose (Kwan, 2002). Within the past decade, there have been various studies with mixed results on the effects of Internet use on travel using the following analytical paradigm: substitution, complementarity, modification and neutrality (Figure 7).

There are a number of additional considerations when relating Internet use to travel including the following:

Whether people live in a more rural or urban area may also affect the frequency of their Internet usage, as well the time they are willing to spend traveling each day. Taking all these considerations into account increases the complexity of drawing definitive conclusions, and it is a topic for further study.

Period events, social trends and technological advancements leave a deep impression on young adults because they are still developing their core values at an early stage of their life cycle. It is difficult to say which formative experiences younger generations will carry forward throughout their life because as people age they tend to become more alike and more like previous generations before them. An example would be the amount of miles someone travels over their lifetime; typically, people travel more in their younger and working years, but as they age, they travel less (as shown in Figure 1). This is a generational travel norm that isn't expected to change much over time, as a person's travel often decreases because of health limitations that occur with age.

Generational norms that change and have a lasting impact may be a result of a unique event or set of circumstances that affect a specific generational cohort. An example may be how the onslaught of new ICTs integrated into daily life has affected the way younger generations communicate and how they are using their time, and whether this is affecting their travel.

Age cohorts are usually defined by decades or significant time periods. People born in the same year, for example, are birth cohorts (generation) for that year.For this study, a cluster analysis was conducted to determine where there are natural "travel behavior breakpoints" among teens and young adults. As a result of the analysis, the age group defined as "youth" in this study is 16-26.

|

Generation Millennial: Profile

|

The integration of new technologies into the American lifestyle as well as the impacts of the 2009 Recession are two of the most defining aspects having affected the lives of many under the age of 30.

A Pew Center survey in February 2010 stated that 37 percent of young respondents were either underemployed or out of work, the highest share within this age group in more than three decades. Long spans of unemployment not only causes depression, anxiety and other health-related issues, but can affect long-term income growth. Because of their financial situation, many young people are delaying marriage, staying in school, and choosing to remain living at home with their parents. Their financial situation also affects their choice of travel mode, whether or not they own a fuel-efficient vehicle and other income-related travel decisions which are made in the context of rising fuel prices and growing transportation costs.

The Millennial generation is the first to grow up with the Internet enmeshed into their daily lives, and their usage far exceeds older age groups. Electronics and technical devices are carried around and attached to them almost as the extension of an arm or hand on the human body. This generation was raised with toy electronics as closely as the Boomer Generation was raised with America’s teddy bears and the Barbie Doll.

Instant communication through evolving technology has caused a shift in how and how often this generation communicates. Many would prefer to receive a text message rather than a phone call, and the iPod and social networking sites are a constant in daily life.

Figure 8: Use of Social Networking by Age

Source: The Pew Research Center, 2010

Some researchers believe that younger persons' preoccupation with the Internet and mobile devices plays a role in reducing their driving because they have become so preoccupied with their mobile devices that they would rather take public transportation than drive. Additional questions have been raised about whether the time that youth spend socializing, shopping and going about their daily activities online replaces any trip making.

Younger generations are also known for openly sharing personal information and being less concerned over privacy issues related to new technologies than older generations. "Tech experts generally believe that today's tech-savvy young people will retain their willingness to share personal information online even as they get older and take on more responsibilities," and that the benefits of personal disclosure "will outweigh their concerns over their privacy," according to a Pew Center report on people's expectations for the future of the Internet.[3] Knowing this, it is possible that this group will be highly accepting of new transportation-related technologies, such as GPS, electronic toll collection, and paying virtually for travel.

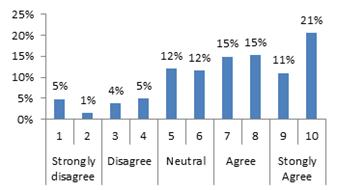

Figure 9: Gen Y Response, "The Environment is an Important Factor when Purchasing a Vehicle"

Source: Deloitte, Automotive Gen Y study, 2010

Younger generations have shown to have environmentally-sensitive viewpoints. In a CNN poll in March of 2012, fifty-one percent of respondents under the age of 50 felt that protecting the environment should be a priority over economic growth.

Although economics still plays a significant role in their car purchasing decisions, recent surveys have shown that young people are influenced by their environmental views when buying a vehicle (Figure 9). As the future innovators of clean energy technologies, they may prefer vehicles that are better for the environment, such as hybrid and/or electric cars and possibly even smaller vehicles. They may also choose other travel options to get them around that require less driving.

Multi-modal Transportation Center in Detroit, MI

San Francisco Bay Area Transit

As metropolitan areas have grown substantially over the past few decades, young people have become accustomed to living in areas with more public transit and land use that supports other travel options. Current trends have shown that younger populations prefer to live in urban areas. Their preference for urban living may affect the way they travel over the long-term, as youth become accustomed to living in areas that are less car-dependent. In high-density areas, youth may also become accustomed to shorter commutes, or given advancements in ICT, they may telework.

Of the most known facts about youth under the age of 30, is that their travel, both VMT and PMT, is decreasing. As shown in the tables below, using data from the National Household Travel Survey (NHTS), there has been an over twenty percent drop in travel among young people ages 16-30 within the past 10 years, and declines in travel since 1995. It should be noted that the 2009 survey data was collected in 2008, at the onset of the recession.

Figure 6: Percent Change in Vehicle Miles Traveled (VMT) and Person Miles Traveled (PMT) for NHTS Survey Years 1995, 2001 and 2009

Survey Year |

Average Annual VMT (per person by age group) |

Percent Change |

||||

16-30 |

31-55 |

56+ |

16-30 |

31-55 |

56+ |

|

1995 |

9,872 |

12,446 |

7,081 |

- |

- |

- |

2001 |

9,748 |

12,892 |

7,951 |

-1.25 |

3.58 |

12.28 |

2009 |

7,319 |

11,493 |

7,781 |

-24.9 |

-10.8 |

-2.06 |

Survey Year |

Average Annual PMT (per person by age group) |

Percent Change |

||||

16-30 |

31-55 |

56+ |

16-30 |

31-55 |

56+ |

|

1995 |

15,524 |

17,041 |

11,309 |

- |

- |

- |

2001 |

15,552 |

18,299 |

12,220 |

0.18 |

7.38 |

8.05 |

2009 |

12,253 |

16,214 |

11,704 |

-21.2 |

-11.3 |

-4.2 |

Historically, VMT has been correlated with a number of influencing factors. Increases in population,income and vehicle ownership are most often associated with rises in VMT; however, recent discussions question whether vehicle ownership should continue to be an influencing factor as a majority of households now have two or three vehicles. For instance, in 2001, the number of household-based vehicles exceeded the number of drivers by 12 million, [4] an indicator that owning a vehicle may no longer be a predictor of future VMT growth, since it is no longer a constraint of auto travel.

Figure 7: Unemployment Rates by Age Group (1948-2012)

As personal travel is highly correlated with economic factors, such as employment and income, economic recessions and/or rising fuel prices are most often associated with declines in VMT. As noted earlier, the most recent recession of 2008 has left many young people jobless or underemployed. Youth unemployment rates have always been higher than non-youth unemployment rates; however, the gap between the two has widened over time (U.S. Department of Labor, various years). In 2008, one in five young workers (16-24) was unemployed, almost three times the unemployment rate of older individuals.

Researchers from the Brookings Institution found that from 2007 to 2010, individuals under the age of 24 experienced the largest decline in employment; in contrast, employment rates among individuals 55 years and older have largely remained stable (Greenstone and Looney, 2010). High unemployment is not only likely to reduce their work travel, but limits the resources they have to spend for other purposes, such as shopping and recreational activities.

Figure 8: Percent of Young People (19-26) Living at Home with Parents (1990, 2001 and 2009), Source: NHTS

High unemployment has also caused many young people to return home to live with their parents. A Pew Center survey found that one-in-eight young adults (ages 22 to 29) had moved back into their parents’ homes after living on their own due to the recession. There has also been a decline in marriage among younger groups and an increase in multigenerational households.

Due to high rates of serious accidents among teenage drivers, graduated licensing policies have been enacted in many states, which have made the process for obtaining a driver's license more lengthy and rigorous. Since 1996, most US States have adopted some form of a graduated licensing, which usually involves a multiple step process for young drivers to get their license, including a minimum number of supervised driving hours, restrictions on the hours of the day young people can drive, as well as on the number of passengers they can carry. Longer waiting periods for obtaining full licensure has risen the licensing age for many to 17 years and above.

Figure 9: Number of States per License Rating

| Ranking | 1990 | 2000 | 2008 |

| License Stringency: Lowest | 42 | 13 | - |

| License Stringency: Low | 9 | 19 | 9 |

| License Stringency: Medium | - | 14 | 12 |

| License Stringency: High | - | 3 | 30 |

In addition to more stringent licensing regimes, many school systems which once offered driver's education as part of the high school curriculum have eliminated the program, shifting the cost of driver's education from the state to parents. Today, only 15 percent of students are enrolled in driver's education through their schools. In many states, driver’s education is mandatory for first-time drivers, so students and/or their families must bear the costs, which may range from $300-$500 per program, depending on the area.

Stringent licensing regimes and the reduction of publically-funded driver education programs may reduce VMT if young people are no longer incentivized to take up driving, but the affect it may have on total travel is uncertain. It is possible that young people will find alternative modes to meet their daily travel needs, such as getting a ride with a parent or friend, using public transit, walking, or using a bicycle. Additionally, the availability student and employer subsidies for public transportation, which have been effective in boosting ridership in certain areas, encourage young people to use other modes of travel.

Where people chose to live is inextricably linked to their travel behavior. In suburban areas, where there are typically greater distances between activities and fewer travel choices, driving has become predominant mode of travel. As suburban areas have experienced the fastest growth in their aging populations, younger populations have shown a preference for city living; however, their preferences for city living may change as young people age and have children. Demographic research has shown that people do not maintain their same preferences throughout their lives, and preferences based on geography may change among young people as they get older and have children. [5]

Figure 10: Housing Preference and Willingness to Make Tradeoff |

|

Source: RCLCO Consumer Research

2007 |

Real estate surveys on Smart Growth, however, have showed that younger home buyers (under age 35) are more accepting of high density neighborhoods, especially if the homes in these areas are well-designed and affordable.[6]

The RCLCO[7] Consumer Research survey found that seventy-seven percent of Gen Y respondents planned to live in an urban area, and two-thirds preferred to live in a community where they could walk to work, shop and go about their daily activities all in close proximity. Gen Y also values access to transit. In a real estate survey by the Concord Group, eighty-one percent reported that it was very or somewhat important for them to live near bus and rail lines, and sixty-seven percent would pay a premium to do so. In the RCLCO survey cited above, over fifty percent of respondents said that meeting green objectives would figure into their housing decisions.[8]

The integration of ICT and mobile phone technologies into the lives of young people are defining elements of their lifestyle. Their daily use of web-based technologies far exceeds older generations. Youth also tend to be early adopters of new communication technologies and quick to assimilate these technologies into their lifestyles.

Figure 11: Use of Technology by Age, Source NHTS

In the realm of today’s rapid adoption of new communication technologies, questions arise as to how this affects the use of a person’s time and thus, how it influences their travel. For instance, are youth spending more time online than in travel? Are their shopping trips to brick and mortar stores being replaced by online purchases? Are they socializing more online than in person? Or does their use of online travel information, such as directions, traffic conditions, or fast payment options, influence their trip making? Research is inconclusive on how the use of ICT increases or substitutes a person’s travel. Studies have shown that individuals use technology in different ways; some use technology to consolidate trips and others use it to reach activity opportunities that require longer travel times. This is a topic for further study, but given the predominance and use of ICT in the lives of young people, it should be considered as a factor that may influence travel.

|

Proposed Hypotheses: Younger generations are traveling differently than previous generations, what is happening and why?

|

There are many factors that influence the travel decisions of youth. Some factors are life cycle-related, while others are influenced by what is occurring in the economy, regulatory environment, transportation system and new technologies. Some factors may have only a temporary affect on travel choices, while others may have a lasting impact and result in the change of travel behavior patterns of future generations.

Figure 12: Potential Explanations for the Travel Differences between Young and Older Adults (2009)

Type of effect |

Characteristics |

Life Cycle |

Delayed marriage |

Multigenerational households |

|

Period |

Economic downturn |

Changes in driver’s licensing laws/regulations |

|

Cohort |

Reliance on technology |

Location/urbanicity |

|

Environmental awareness |

The purpose of the work under FHWA’s Next Generation of Travel project has been to explore factors that are influencing the travel behavior of youth and are shaping the way they travel. These factors have been explored quantitatively, using data from the Nationwide Personal Transportation Survey (NPTS- 1990) and the National Household Travel Surveys (NHTS-2001 and 2009) and qualitatively, through seven focus groups that were held at different sites around the country. The quantitative analysis involved the development a set of statistical models to analyze four selected travel-related measures, including: person miles traveled (PMT), activity participation (number of daily trips); journey-to-work (commute) mode choice and travel mode used for social trips. The focus of the qualitative analysis was to develop a better understanding of the thoughts related to the travel differences and preferences between youth and non-youth and to support or add new insight to the findings of the quantitative analysis. The results of these analyses are detailed in supporting documents to this report, What’s Youth Got to Do With It? Exploring the Travel Behavior of Teens and Young Adults (2012) and Next Generation of Travel Research: Qualitative Report (2012), and are available on the FHWA-HPTS Webpage: https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/policy/otps/transfutures.cfm

This section presents a summary of our findings, which identify generation shifts in travel behavior, the predominate role of the economy in influencing travel decisions, and other factors that may be contributing to the changes in the way youth are traveling.

Employment status, household income and other measures of economic status have shown to have a significant influence on all aspects of youth and adult travel behavior across all generations. Changes in the economy help to explain the growth in mobility, trip-making and driving among both youth and adults during the 1990s and the subsequent contraction of mobility, trip-making, and driving during the 2000s.

Figure 13: Percentage of Youth Working By Age and Year (1990, 2001, 2009)

Between 2001 and the recession of 2009, personal travel (per person) nationally dropped substantially, and most especially among young people. At the same time, the percentage of youth working under the age of 26 has dropped compared to youth from previous decades.

Among all the variables analyzed, economic factors have the greatest influence on personal travel across all age groups. Education, employment, auto access and being a driver are all positively associated with PMT.

Figure 14: PMT and Variables of Interest (1990, 2001, 2009)

Yellow (+) indicates positive and statistically-significant relationship; red (-) indicates negative and statistically-significant relationship; and blue (0) indicates no statistically-significant relationship.

| Teen (15–18) | Young Adult (19–26) |

Adult (27–61) | |||||||||

| 1990 | 2001 | 2009 | 1990 | 2001 | 2009 | 1990 | 2001 | 2009 | |||

| Worker Status | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| Young Adult Living at Home | (Not Included) | 0 | 0 | 0 | (Not Included) | ||||||

| Technology (Web Use) | n/a | 0 | + | n/a | 0 | + | n/a | 0 | + | ||

| License Stringency | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | ||

Income and employment are also associated with greater levels of trip-making. Trips per person increased between 1990 and 2001, but declined between 2001 and the Recession of 2008.

Figure 15: Number of Trips and Variables of Interest (1990, 2001, and 2009)

| Teen (15–18) | Young Adult (19–26) |

Adult (27–61) | |||||||||

| 1990 | 2001 | 2009 | 1990 | 2001 | 2009 | 1990 | 2001 | 2009 | |||

| Worker Status | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| Young Adult Living at Home | (Not Included) | 0 | 0 | 0 | (Not Included) | ||||||

| Technology (Web Use) | n/a | 0 | + | n/a | 0 | + | n/a | 0 | + | ||

| License Stringency | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | ||

People our age are carrying significant amounts of student loan debt. When you look at your opportunity to buy a car, and have several hundred dollars of debt each month because you have to repay your student loan—that really takes the car payment off the table.—Washington, D.C. |

As voiced through the focus groups, personal finances play a large role in decisions to own a vehicle. Youth especially, living on constrained budgets often burdened by student loan debt, see the expense of gas (namely), upkeep and parking as a primary reason for not owning a vehicle. Some youth are saving their money to buy a car, as they see it as something to be acquired when they are more settled in a career and/or with a family of their own. Most see themselves owning a vehicle at some point in the future.

The presence of children in the household is most often associated with greater personal travel among adults. Among teen and young adults, however, living at home was observed statistically to have no effect on their travel.

GDL restrictions imposed by the states have played a role in the decline of licensure among young people, but have statistically shown not to reduce their travel over the long-term. More teens are licensing later, but most do eventually obtain a license and drive.

Although GDL restrictions are associated with less travel among young people over the short term, they are, interestingly enough associated with higher occurrences of trip-making. Why? Possible reasons may be that unlicensed youth are, in the meantime, traveling more using other modes, are being chauffeured by parents and friends, and/or are ignoring restrictions.

A correlation that possibly shows that trip making is not affected by licensure is the frequent use of transit among commuters in states with strict GDL restrictions. Additionally, youth in the focus groups who primarily lived in areas where transit was not an option, expressed that they anticipated owning a car or having access to a car once they had obtained a license.

If you live in the city, a car is almost like a luxury, as opposed to a requirement if you live in the suburbs.—Boston, MA |

Population density was shown in the quantitative analysis to be negatively associated with PMT across all age categories and years. In the focus groups, geographic location, coupled with finances played the greatest role in whether or not youth owned a vehicle. For many youth, the effects of the recession on their employment prospects, housing expenses (which may be especially high in downtown locations) and added student loan debt, made living in area that provided sound transit services and other inexpensive and convenient means of getting around very desirable. City dwellers did not feel that it was necessary to own or have access to a vehicle, unlike youth who lived in car dependent areas who viewed their vehicle as a necessity. This finding is in line with previous research which has shown that geographic characteristics, such as population density and metropolitan area size, affect commute mode choice.

Figure 17: Commute Mode for Youth (1990, 2001, 2009)

The likelihood of driving alone to work has shown to be diminishing over time. People born in the 1980s and 1990s show a diminishing probability of driving alone.[9] Although no definite conclusions can be drawn, there is certain ongoing research that suggests that the rate of commuting by car among those under the age of thirty–five is steadily decreasing, possibly indicating that more youth are commuting by other modes than youth in previous generations (Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2010)

Other findings of mode use that have been explored through the quantitative analysis:

Transit Use—Individuals are more likely to use transit in denser areas and in cities with robust transit systems, like New York City. Those with higher incomes are less likely to use transit.

With regards to social trips, the probability of taking transit increases with distance for youth in all three survey years, with the exception of traveling on weekends. As youth age from their teens to their 20s, they are less likely to use transit for social trips.

Biking—People are less likely to bicycle as trip distance increases. Women are also less likely to bicycle than men. Income is not related to the likelihood of biking among youth but is negatively related to bicycling among adults in two of the survey years.

Walking—People are less likely to walk as their incomes and trip distances increase. They are, however, more likely to walk in dense urban environments. Immigrants and people living in the New York City are more likely to walk for social and recreational purposes than are others.

Buses run frequently, it’s environmentally–friendly; there are lots of routes and the technology is great!—San Francisco, CA |

Participants in the focus groups did not express that their environmental views had a significant impact overall on their decisions to own a car. Concerns about the effect of driving on the environment were voiced stronger among youth who lived in certain locations. In the Washington D.C. area, for instance, almost all participants thought that their future car purchases would be either a hybrid or electric vehicle, based on the knowledge that these vehicles were better for the environment. In other locations, either little was known about hybrid and/or electric vehicles, or reasons for purchasing these vehicles was more related to getting better gas mileage rather than for the environmental benefits.

The use of ICT, measured as daily web use in the NHTS, did not decrease travel; in fact, it tended to be associated with increasing travel (which was mostly the case in comparisons made using the 2009 NHTS). This suggests that when daily web use affects travel, it appears to complement travel, not substitute for it. Such increases may be attributed to an income effect, as daily web use is correlated with income, which is highly associated with PMT. Currently, the availability of data needed to do a more robust analysis is lacking.

In a car, I’d have to be actively engaged in my commute, whereas now I can nap or read.—Washington D.C |

When questions were posed to youth about how their use of ICT affects their travel, many were slow to respond, as it was a topic that seemed to require more thinking. Youth who regularly engaged in everyday activities using the web applications on their phones, viewed them as significantly improving their day to day activities and travel experiences through saved time and added convenience.

With technology you are in constant contact with people and at least for me, I am more likely to go see them.—Portland, OR |

Youth who engaged in online shopping and banking were unsure about how this affected their travel, and admitted that they most often did not make their online purchases as a conscious decision to reduce their travel. Most did not see social media tools and online communication platforms replacing their in-person socializing with friends (who lived in the general vicinity), but rather as a way to keep connected with their friends and family on an immediate basis.

Youth did not view teleworking as desirable at this stage in life, given their need for interaction with peers in the workforce and their desire to engage in activities outside of the home.

Privacy concerns related to use of ICT technologies were minimal. Many saw major companies like Google and Facebook as having a lot of information about them already. Many saw tracking and mapping applications adding convenience to their lives by making traveling easier and potentially influencing their routes. Some youth expressed opinions that if an agency was collecting data about them, they would want to know how this data would be used and that it would be properly protected.

I think that we are always willing to sacrifice these liberties (privacy) for convenience or other things.—San Francisco, CA |

In an age of increasing urbanization and modal choices, is the car still a symbol of freedom for youth as it has been for previous generations? Albeit economic constraints, for most youth, the answer is "yes." The car is still recognized as adding convenience to everyday life by giving people the ability to go about their daily activities as they please, as well as an effective means for transporting others and personal goods. Cars of the future may become smaller, safer, more fuel efficient, and even driverless; however, the impact they will have on the traveling public thirty to forty years from now will remain significant.

For everyone, your first car means one thing—freedom.—Richmond, VA |

Anable, Jillian. "‘Complacent Car Addicts’ or ‘Aspiring Environmentalists’? Identifying travel behavior segments using attitude theory." Transport Policy. Volume 12, 2005. (pg. 65–78).

Anderson, Janna and Lee, Rainie, "Millennials will make online sharing in networks a lifelong habit," Pew Research Center’s Internet and American Life Project, July 9, 2010

APTA. "It Pays to Ride Public Transportation." Pamphlet of the American Public Transportation Association, March 2009. Available at: <http://www.apta.com/resources/bookstore/Documents/2009 It Pays to Ride Transit.pdf>

Associated Press. "Some schools drop driver’s ed to cut costs."MSNBC.com US News: Education. Dec. 18, 2009. Accessed online Jan. 14, 2011. <http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/34483262/ns/us_news-education/>

Bamberg, Sebastian, and Peter Schmidt. "Changing Travel-Mode Choice as Rational Choice: Results from a Longitudinal Intervention Study." Rationality and Society. Vol. 10 (2), May 1998.

Blumenberg, Evelyn, Brian Taylor, Michael Smart, Kelcie Ralph, Madeline Wander and Stephen Brumbaugh, What’s Youth Got to Do With It? Exploring the Travel Behavior of Teens and Young Adults, University of California-Los Angeles, Institute of Transportation Studies, 2012

Booz Allen Hamilton. "Energy Trends: New Hybrids Breaking Out of Niche?" Booz Allen, 2004.

Boston Consulting Group. "Batteries for Electric Cars: Challenges, Opportunities and the Outlook to 2020." Boston Consulting Group, 2010. Accessed online Jan. 10, 2011. <http://www.bcg.com/documents/file36615.pdf>

Black, Lee, Jack Mandelbaum, Indira Grover, and Yousuf Marvi. "The Arrival of ‘Cloud Thinking.’" Management Insight Technologies White Paper. November 2010.

Bressler, Jeff. "Generation Y, the Green Car Generation." Autrotropolis.com. Accessed online. Jan 3, 2011. <www.autotropolis.com/wiki/index.php?title=Generation_Y,_the_Green_Car_Generation>

Brokaw, Tom. "Tom Brokaw Reports: Boomer$." CNBC. March 2, 2010, Available at <http://www.cnbc.com/id/34840866/>

Brokaw, Tom. "The Greatest Generation," Random House, 1998.

Business Dictionary.com, <http://www.businessdictionary.com/definition/cohort.html>

Campbell, S.M., Hoffman, B.J., & Lance, C.E., Twenge, J., "Generational Differences in Work Values: Leisure and Extrinsic Values Increasing, Social and Intrinsic Values Decreasing" <http://jom.sagepub.com/content/early/2010/03/01/0149206309352246.full.pdf> August 6, 2010.

Capgemini. Cars Online 07/08: Responding to Changing Consumer Trends and Buying Behavior. Accessed online Jan 11, 2011. <https://www.capgemini.com/resource-file-access/resource/pdf/Cars_Online_07_08.pdf>

Capgemini. Cars Online 09/10: Responding to Changing Consumer Trends and Buying Behavior. Accessed online Jan 11, 2011. <http://www.us.capgemini.com/news-events/press-releases/Capgemini-Cars-online-study/>

Center for Disease Control. "U.S. Teen Birth Rate Hits Record Low in 2009, CDC Report Finds, Total births and fertility rate also down." Center for Disease Control Press Release. CDC National Center for Health Statistics Office of Communication December 21, 2010. Accessed online January, 28, 2011.

Center of Neighborhood Technology, Chicago, IL, http://www.cnt.org/

Changewave Research. Corporate Smart Phones and Tablets - 1Q 2011 Business Spending Outlook, December 1, 2010.

Cisco. "Cisco Study Finds Telecommuting Significantly Increases Employee Productivity, Work-Life Flexibility and Job Satisfaction." Accessed online 12/8/2010. <http://newsroom.cisco.com/dlls/2009/prod_062609.html?print=true>

Choo, Sangho, Particia Mokhrarian, and Ilan Salomon. "Impacts of Home-Based Telecommuting on Vehicle-Miles Traveled: A Nationwide Time Series Analysis." A study prepared for the California Energy Commission (UCD-ITS-RR-02-05), October 2002. <https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/policy/otps/telecommutingOct2012.pdf

Choo, Sangho, Particia Mokhrarian, and Ilan Salomon. "Does Telecommuting Reduce Vehicle Miles Traveled? An Aggregate Time Series Analysis of the US." Transportation 32(1), 2005, 37-64 July 2004. <http://econwpa.repec.org/eps/em/papers/0505/0505001.pdf>

Cheung, Edward. Baby Boomers, Generation X and Social Cycles, 1995, p.97., P. Taylor, Pew Center Conference, Washington, D.C., 2010.

Clean Air Campaign. "Tax Benefits." Accessed online Jan 17, 2011. <www.cleanaircampaign.org/Our-Services/Employer-Services/Tax-Benefits>

ComScore. "Mobile Facebook, Twitter Growth Explodes." Accessed online January 6, 2011. <http://www.marketingcharts.com/interactive/mobile-facebook-twitter-growth-explodes-12179/>

Contrino, Heather and Nancy McGuckin. "An Exploration of the Internet’s Effect on Travel." August 1, 2006.

Copeland, Larry. "Driver’s ed set for revival in public school." USA Today. Sept. 29, 2009. Accessed online Jan. 14, 2011. <http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/nation/2009-09-28-drivers-ed_N.htm>

Copeland, Michael V. "The hydrogen car fights back", Fortune magazine, October 14, 2009.

Crane, Randall. "Is There a Quiet Revolution in Women’s Travel?" Journal of the American Planning Association 73 (3), 2007. Deloitte and Touch "A new era: Accelerating toward 2020 – An automotive industry transformed." Deloitte and Touche, 2009.

Dargay, Joyce, Dermot Gately, and Hillard G. Huntington. "Price and Income Responsiveness of World Oil Demand, by Product." New York University Working Paper December 20, 2007.

Deloitte Development LLC. "Generation Y: powerhouse of the global economy Restless generation is a challenge–and a huge opportunity–for employers." <http://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/us/Documents/human-capital/us-consulting-hc-generationy-snapshot-041509.pdf>

Dieringer Research Group Inc. "WorldatWork Telework Trendlines." Dieringer Research Group Inc., 2009.

Doyle, D., & Taylor, B. "Variation in metropolitan travel behavior by sex and ethnicity." In Travel patterns of people of color: Final report. Columbus, Ohio. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration, 2000.Goldberg P. K., "The Effects of the Corporate Average Fuel Efficiency Standards." Journal of Industrial Economics, Vol 46 (4), 1998 (pgs1-33).

Effectiveness and Impact of corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) Standards, Board on Energy and Environmental Systems, The National Academy of Sciences, 2002.

Facebook. "Facebook Statistics." Accessed online Jan. 7, 2011. And ComScore. "Mobile Facebook, Twitter Growth Explodes." Accessed online January 6, 2011. <http://www.marketingcharts.com/interactive/mobile-facebook-twitter-growth-explodes-12179/>

Fairfield, Hannah. "Driving Shifts into Reverse." The New York Times. New York Edition page BU7. May 2, 2010.

Festin, Scott M. "Summary of National and Regional Travel Trends: 1970-1995." US Department of Transportation Federal Highways Administration May 1996 .

First Data Government and Transit Task Force. "Transit Payment Systems: A Case for Open Payments". 2010. <http://www.fundxpress.com/downloads/thought-leadership/transit-payment-systems_wp.pdf>

Flamm, Bradley. "Environmental Knowledge, Environmental Attitudes, and Vehicle Ownership and Use." A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley, Fall 2006.

Flamm, Bradley. "Environmental Knowledge, Environmental Attitudes, and Vehicle Ownership and Use." A presentation to the TRB Annual Meeting, January 23, 2007.

Fletcher, Dan. "Facebook: Friends Without Borders," Time Magazine, May 2010

Frey, William H., Metro America in the New Century: Metropolitan and Central City Demographic Shifts Since 2000, The Brookings Institute, 2005.

Gately, Dermot and Hillard G. Huntington. "The Asymmetric Effects of Changes in Price and Income on Energy and Oil Demand."The Energy Journal 23(1), 2002. (pgs. 19-55).

Glenn, Norval D., "Cohort Analysis" Sage Publications, Inc., 1977

Goldin, C., Katz, L., & Kuziemko, I. "The homecoming of American college women: The reversal of the college gender gap." Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 20(4), 2006 (pgs 133-156).

Golob, Thomas. "Impacts of Information Technology on persona travel and commercial vehicle operations: research challenges and opportunities." TRB. June 2000.

Gossen, Rachel and Charles L. Purvis, "Activities, Time, and Travel Changes in Women’s Travel Time Expenditures, 1990–2000"Greene D.L., J.R. Kahn and R.C. Gibson, "Fuel Economy Rebound Effect for US Households." Energy Journal, Vol 20 (3), 1999 (pgs 1-31).

Greed, Clara. "Are we there yet? Women and Transport Revisited" in Gendered Mobilities. Burlington ,VT: Ashgate Publishing, 2008.

Gregory, Ted. "Fewer 16-year-olds in Illinois have driver's licenses." Chicago Tribune, June 22, 2010. <http://articles.chicagobreakingnews.com/2010-06-22/news/28514675_1_licenses-rob-foss-teen-drivers>

Harris Interactive. "Cloud Computing: Final Report." Harris Interactive Public Relations Research. September 24, 2010.

Hiroyuki, Iseki. "Survey on Status of Knowledge and Interest of Smartcard Fare Collection Systems among US Transit Agencies".2006. <http://its.berkeley.edu/sites/default/files/publications/UCB/2006/PRR/UCB-ITS-PRR-2006-12.pdf>

Holguin-Veras, Jose, Kaan Ozbat, and Allison de Cerreño. "Evaluation Study of Port Authority of New York and New Jersey’s Time of Day Pricing." March 2005. NJ Department of Transportation. FHWA/NJ-2005-005.

Huso, Deborah. "It’s All in the Family," Washington Post Homebuyers Guide, The whole Family Edition. April 2010.

Hybridcars.com, "Profile of Hybrid Drivers." March 31, 2006. Accessed online <http://www.hybridcars.com/hybrid-drivers/profile-of-hybrid-drivers.html>

IBM Group. Future Focus: Travel. White Paper June 2009. <https://www.304.ibm.com/businesscenter/cpe/download0/177501/IBM_White_Paper_3.pdf >

IE Market Research. "3Q. 2010. US GPS Navigation and Location Based Services Forecast." IEMR, July 1, 2010.

Jake on Jake on Jobs.com, "Work/Life Balance Isn’t Healthy for 20-Somethings," February 14, 2009.

Jones, Sydney, and Susannah Fox, "Generations Online in 2009 "Pew Internet & American Life Project." January 28, 2009.

Karaca-Mandic, Pinar and Greg Ridgeway. "Behavioral Impact of Graduated Drivers Licensing on Teenage Driving Risk and Exposure." Journal of Health Economics, vol. 29 (1), 2010 (pgs 48-61).

Kelley, Debbie. "Human Resource Expert: Prepare now for post-recession market." Colorado Springs Gazette. August 11, 2009. Accessed online: <www.gazette.com>

Kotkin, Joel. The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050, The Penguin Press, NY, 2010.

La Rue, Todd. "Multigenerational Demand for Urbanism." RCLCO presentation at the CNU XVI in Austin Texas.

Lenhart, Amanda, Kristen Purcell, Aaron Smith and Kathryn Zickuhr. "Social Media and Mobile Internet Use Among Teens and Young Adults" Pew Research Center’s Internet and American Life Project. February 3, 2010. <http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2010/Social-Media-and-Young-Adults.aspx>

Litman, Tod. The Future Isn’t What It Used To Be: Changing Trends and Their Implications for Transport Planning, Victoria Transport Policy Institute, Canada, July 2010.

Logan, Gregg Stephanie Siejka and Shyam Kannan. "The Market for Smart Growth." A report by RCLCO prepared for the EPA. Accessed online February 2, 2011. http://www.epa.gov/smartgrowth/pdf/logan.pdf>

Madland, David, Teixeira, Ruy. "New Progressive America: The Millennial Generation", Center for American Progress, May 13, 2009, <https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/progressive-movement/report/2009/05/13/6133/new-progressive-america-the-millennial-generation/>

Martin, Scott. "New Study Reveals More about Map and GPS Habits." GPS Lodge. August 16, 2006. Accessed online Dec. 22, 2010. <http://www.gpslodge.com/archives/006968.php>

"Maximizing the value of telepresence." Frost and Sullivan White Paper.

McGukin, Nancy and Yukiko Nakamoto. "Differences in Trip Chaining by Men and Women." Research on Women’s Issues in Transportation. TRB Conference Proceedings #35. Chicago, Il: November 18-20, 2004.

McGuckin, N., and E. Murakami. "Examining Trip- Chaining Behavior: Comparison of Travel by Men and Women." Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, No. 1693, TRB, National Research Council, Washington, D.C., 1999, (pp. 79–85). http://nhts.ornl.gov/1995/Doc/Chain2.pdf

Meeker, Mary. Internet Trends 2010. April 12, 2010. Morgan Stanley Research. Accessed online 1/3/2010. <http://conversations.marketing-partners.com/2010/06/internet-trends-2010-by-morgan-stanley’s-mary-meeker/>

Metro America in the New Century: Metropolitan and Central City Demographic Shifts, The Brookings Institution, 2005.

Mildwurf, Bruce. "State deficit could put brakes on driver's ed classes." WRAL. April 7, 2010. Accessed online Jan 14, 2011. <http://www.wral.com/news/local/politics/story/7378142/>

Miller, Virginia. "Telling the Story of Public Transportation’s Positive Environmental Impact" American Public Transportation Association Press Release. April 21, 2010.

Mokhtarian P L, "A Typology of Relationships between Telecommunications and Transportation" Transportation Research Part a-Policy and Practice. Vol. 24, 1990 (pgs 231-242).

Mokhtarian P L, "A conceptual analysis of the transportation impacts of B2C e-commerce" Transportation. Vol. 31, 2004 (pgs 257-284).

Mokhtarian P L, Circella G, "The role of social factors in store and internet purchase frequencies of Clothing/Shoes", in workshop proceedings of: The international workshop on Frontiers in Transportation: Social Interactions. Amsterdam, Netherlands: 2007.

Morello, Carol. "Suburbs Taking on a More Diverse Look," Washington Post, May 9, 2010.

Multisystems, Inc. "Fare Policies, Structures and Technologies: Update". 2003. TCRP Report 94. <http://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/tcrp/tcrp_rpt_94.pdf>

Neff, Jack. "Is Digital Revolution Driving Decline in U.S. Car Culture?" Advertising Age, May 2010.

National Journal. Millennials: Just Kind of Doing My Own Thing. 2010 (pgs 66-68).

National Surface Transportation Policy and Revenue Commission Briefing Paper 4A-05: Implication of Rural/Urban Development Patterns on Passenger Travel Demand, January 2007.

National Surface Transportation Policy and Revenue Commission Briefing Paper 4A-04: Implications of Regional Migration on Passenger Travel Demand, January 2007.

National Surface Transportation Policy and Revenue Commission Briefing Paper 4H-01: Potential Impacts on Increased Telecommuting on Passenger Travel Demand, January 2007.

National Surface Transportation Policy and Revenue Study Commission, Briefing Paper 4A-03: Implications of Alternative Assumptions Concerning Future Immigration on Travel Demand for Different Modes, January 2007.

National Surface Transportation Policy and Revenue Study Commission, Briefing Paper 4A-02: Implications of Aging on Passenger Travel Demand for Different Modes, January 2007.

National Surface Transportation Policy and Revenue Study Commission, Commission Briefing Paper 4A-06, Implications of Rising Household Income on Passenger Travel Demand, 2007.

Glenn, Norval, Cohort Analysis, Sage Publications, 1977

Oregon Department of Energy. "Oregon Department of Energy- Transportation." Accessed online Jan 17, 2011 <https://www.oregon.gov/energy/TRANS/Pages/transhm.aspx>

Our Nation’s Travel: Current Issues, 2001 National Household Travel Survey, USDOT-FHWA, Publication No. PL-05-015, 2001.

Parka, Sung Y. and Guochang Zhaoc, "An estimation of U.S. gasoline demand: A smooth time-varying cointegration approach" Energy Economics. Volume 32, Issue 1, January 2010 (pgs 110-120).

Pascal, Jeffrey and and D'Vera Cohn. "Immigration to Play Lead Role In Future U.S. Growth." Pew Research Center, February 11, 2008.

Pendyala R M, K G Goulias, and R Kitamura. "Impact of Telecommuting on Spatial and Temporal Patterns of Household Travel" Transportation. Vol. 18, 1991 (pgs 383-409).

Pisarski, Alan, Commuting in America III: The Third National Report on Commuting Patterns and Trends, Transportation Research Board, 2006, pg. 19 Price Waterhouse Cooper. "Capitalizing on Change: The Electric Future of the Automotive Industry." Price Waterhouse Coopers Global Automotive Perspectives Services, 2009.

Pisarski, Alan. Commuting in America III: The Third National Report on Commuting Patterns and Trends, Transportation Research Board, 2006.

Plug-In Cars: Powering America Towards a Cleaner Future, Environment Texas Research and Policy Center, Siena Kaplan Frontier Group, Rob Sargent Environment America Research & Policy Center, January 2010.

Price Waterhouse Cooper. "Capitalizing on Change: The Electric Future of the Automotive Industry." Price Waterhouse Coopers Global Automotive Perspectives Services, 2009.

Salomon, I. "Telecommunications and Travel Relationships - a Review" Transportation Research Part a-Policy and Practice. Vol. 20, 1986 (pgs 223-238).

Schofer, Joseph, Frank Koppel, and William Charlton. "Perspectives on Driver Preferences for Dynamic Route Guidance Systems." Transportation Research Record. Vol. 1588, TRB, 1997 (pgs 26-31).

Shaputis, Kathleen. The Crowded Nest Syndrome, Clutter Fairy Publishing, 2004.

Singer, Audrey. "Immigration." The State of Metropolitan America. Brookings Institution. Accessed online February 16, 2011. <http://www.brookings.edu/metro/MetroAmericaChapters/immigration.aspx>

Small, Kenneth A. and Kurt Van Dender. "Fuel Efficiency and Motor Vehicle Travel: The Declining Rebound Effect." Energy Journal, vol. 28, no. 1 (2007), pp. 25-51.

Smith, Aaron. "Home Broadband 2010." Pew Research Center’s Internet and American Life Project. August 11, 2010. <http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2010/Home-Broadband-2010.aspx>

Smith, A. M., J. Pierce., R. Upledger., and P.A. Murrin. "Motor vehicle occupant crashes among teens: impact of the graduated licensing law in San Diego." 45th Annual Proceeding of the Association for Advancement of Automotive Medicine. Barrington, IL: AAAM, 2001 (pgs. 379–385).

Society for Human Resource Management/National Journal Congressional Poll (on energy and climate change policies), Pew Center, June 2010.

"State Departments of Transportation Lead the Way Using New Media", AASHTO Communications Brief, February 2010.

State of Metropolitan America: On the Front Lines of Demographic Transformation, The Brookings Institution, Metropolitan Policy Program, 2010.

Sweeney, R. "Millennial Behaviors & Demographics", 2006 New Jersey Institute of Technology.

The Pew Research Center, "Recession Turns a Graying Office Grayer," 09/03/2009. <http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2009/09/03/recession-turns-a-graying-office-grayer/>

The Pew Research Center. Millennials: A Portrait of Generation Next: Confident, Connected and Open to Change, Washington, D.C. 2010.

The Pew Research Center. Portrait of Millennial Conference, Newseum, Washington, D.C., 2010.

The Pew Research Center. Generations and their gadgets, Washington, D.C. February 2011, http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2011/Generations-and-gadgets.aspx

The Infinite Dial 2010: Digital Platforms and the Future of Radio, 18th Edison Research/Arbitron Internet and Multimedia Study, May 2010.

Thornhill, M. & Martin J., Boomer Consumer, LINX Corp.

"TomTom Survey Reveal Interesting Facts about Drivers." Accessed online December 22, 2010. <http://www.gpslodge.com/archives/027579.php>

Tonn B E, Hemrick A, "Impacts of the Use of E-Mail and the Internet on Personal Trip-Making Behavior" Social Science Computer Review. Vol 22, 2004 (pgs 270-280).

"Transit Subsidy will Drop $110/ month unless extended, APTA Warns." Weekly Transportation Report: AASHTO Journal. December 3, 2010.

Transport for London. "Transport for London’s Oyster Card". 2007. <https://oyster.tfl.gov.uk/oyster/entry.do>

TRB Special Report 220: A Look Ahead Year 2020, Transportation Research Board Committee for Conference on Long Range Trends and Requirements for the Nation’s Highway and Public Transit Systems, 1998.

Trong, Stephanie. Sky, Delta Airlines: The M Factor, 2010 (pgs 70-73, 100-105).

US Department of Transportation. FHWA. "NPTS Brief: Mobility and the Melting Pot". January 2006. www.nhts.ornl.gov Valdez-Dapena, Peter. "All that hype won’t sell electric cars." CNN Money. October 27, 2010. Accessed online Jan 11, 2011. < http://money.cnn.com/2010/10/27/autos/jdpa_hybrid_electric_study/index.htm>

U.S. Department of Energy. Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy. Retrieved from <http://www.fueleconomy.gov/>

U.S. Energy Information Administration, Office of Integrated Analysis and Forecasting, U.S. Department of Energy, 2010. Available at <http://www.eia.gov/oiaf/aeo/aeoref_tab.html>

Valdez-Dapena, Peter. "All that hype won’t sell electric cars." CNN Money. October 27, 2010. Accessed online Jan 11, 2011. <http://money.cnn.com/2010/10/27/autos/jdpa_hybrid_electric_study/index.htm>

Wachs, M. "Men, women, and wheels: The historical basis of sex differences in travel patterns." Transportation Research Record, Vol. 1135, 1987 (pgs 10-16). And Wachs, M. "Men, women, and urban travel: The persistence of separate spheres." In M. Wachs & M. Crawford (Eds.), The car and the city: The automobile, the built environment, and daily urban life. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1991.Wald, Matthew, "U.S. Drops Research Into Fuel Cells for Cars," New York Times, May 7, 2009.

Wald, Matthew, "U.S. Drops Research Into Fuel Cells for Cars," New York Times, May 7, 2009. <www.nytimes.com/2009/05/08/science/earth/08energy.html> retrieved 9 May 2009

Walls, Margaret and Elena Safiro. "A review of the literature on telecommuting and its implication for vehicle travel and emissions." Resources for the Future. Discussion Paper 04-44. December 2004.

Wilson R, Krizek K, and S. Handy. "Trends in Out-of-Home and At-Home Activities: Evidence from Repeat Cross-Sectional Surveys" Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board. Vol. 2014, 2007 (pgs 76-84).

Worchester Polytechnic Institute. "Geolocation, Next Phase of the Social Media Revolution, Focus of June 14 Workshop at WPI." June 8, 2010. Accessed online Jan. 6, 2011. <http://www.wpi.edu/news/20090/wireless2010.html>

Wronski, Richard. "RTA looks into potential of riders using cell phones instead of tickets or transit cards". May 2009. <http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2009-05-26/news/0905250222_1_cell-phones-debit-cards-fare>

Yamashita, Tomohisa, Kiyoshi Izumi and Koichi Kurumatani. "Analysis of the Effect of Route Information Sharing on Reduction of Traffic Congestion." In Application of Agent Technology in Traffic and Transportation. Whitestein Series in Software Agent Technologies and Autonomic Computing, 2005.

Yannan, Tuo. "GPS-enabled phones the next "must have"." China Daily. Jan. 14, 2011. Accessed online Jan 17, 2011 <http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/business/2011-01/14/content_11855043.htm>

Young, Peg. "Upward Trend in Vehicle-Miles Resumed During 2009." Transportation Trends in Focus. Department of Transportation. April 2010.

[1] The Pew Research Center, Millennials: A Portrait of Generation Next, Confident, Connected, Open to Change, February 2010, pg. 9

[2] Figure 2: A Heavy Load: The Combined Housing and Transportation Burdens of Working Families, Center of Neighborhood Technology, October 2006, pg. 1

[3] Anderson, Janna and Lee, Rainie, "Millennials will make online sharing in networks a lifelong habit," Pew Research Center’s Internet and American Life Project, July 9, 2010, pg. 1

[4] Our Nation’s Travel: Current Issues, 2001 National Household Travel Survey, USDOT-FHWA, Publication No. PL-05-015, 2001, pg. 6

[5] Kotkin, Joel, "The Geography of Aging: Why Millennials are Headed to the Suburbs." December 9, 2013

[6] Logan, Gregg Stephanie Siejka and Shyam Kannan. "The Market for Smart Growth." A report by RCLCO prepared for the EPA. Accessed online February 2, 2011. < http://www.epa.gov/smartgrowth/pdf/logan.pdf>

[7] Robert Charles Lesser and Company

[8] La Rue, Todd. "Multigenerational Demand for Urbanism." RCLCO presentation at the CNU XVI in Austin Texas.

[9] What’s Youth Got to Do With It? Exploring the Travel Behavior of Teens and Young Adults, University of California-Los Angeles, Institute of Transportation Studies, 2012, pg. 103