U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

Federal Highway Administration Research and Technology

Coordinating, Developing, and Delivering Highway Transportation Innovations

| REPORT |

| This report is an archived publication and may contain dated technical, contact, and link information |

|

| Publication Number: FHWA-HRT-14-034 Date: August 2014 |

Publication Number: FHWA-HRT-14-034 Date: August 2014 |

This chapter presents analysis of the benefits and costs of performance bonds. Additionally, this chapter determines a default rate for the industry.

The benefits a State transportation department receives from a performance bond are derived from three different phases of the project: before the contract, during the contract, and after a claim is filed. However, the State transportation department receives financial benefits from a performance bond only after a claim is filed. There is some dispute about the value of the benefits during the contract, however. Because the near-miss benefit (explained below) claimed by the sureties could not be validated during the case studies and there was no data pertaining to the near misses, it was not included as a financial benefit.

The benefits received by the State transportation department before the contract begins result from the typical long-term relationship between the surety and the contractor and the surety’s use of enterprise risk management2 to underwrite the performance bond. The long-term relationship between a surety and a contractor allows the surety to understand the contractor’s business plan and assess the contractor’s managerial capacity to execute that plan. When a surety, as a creditor, uses the enterprise risk management approach to underwrite a contractor, it gives the contractor the incentive to adopt the enterprise risk management discipline in its own management and governance. The cost of each of these benefits is included in the cost of the premium for the performance bond.

The sureties state that benefits the State transportation department receives during the contract result from the surety’s effort to sustain a contractor during the project and the ability of the State transportation department to use the threat of calling the surety to improve contractor performance. Like a lender, the surety can intervene to prevent failures and losses in ways that the State transportation department cannot; the result of this proactive effort is referred to as “near misses.” The validity of this benefit is disputed in the industry. During the case studies performed for this investigation, none of the State transportation departments had experienced a surety proactively working with an at-risk contractor before the State transportation department reported a problem with a contractor. In fairness, the State transportation department may not ever know that the surety is working with the contractor behind the scenes. However, because the sureties’ claims of the existence of near misses could not be validated, it was not included as a financial benefit, and yet any costs associated with this purported benefit are included in the premium for the performance bond.

During the case studies performed with five State transportation departments, it was reported that the biggest benefit of having a performance bond during a project is the department’s ability to threaten to call the surety if the contractor’s project performance does not improve. The performance bond premium assigned to a contractor for a specific project is based on the financial risk of the contractor. As a result, a contractor does not want the State transportation department to report poor performance on an ongoing project to the surety, because such a report is likely to impact the surety’s evaluation of the contractor’s financial risk on future projects, which could potentially increase the contractor’s premium rate on future performance bonds. This would disadvantage the contractor on future bids.

After a claim is filed, the benefit the State transportation department receives depends on the option taken by the surety to remedy the default. Once a project defaults, the surety can pay damages to the State transportation department, assume the role of the contractor and complete the project, or hire a new contractor to complete the project. The benefits of each option have a financial value, and the costs associated with these benefits are included in the premium cost of the performance bond. The benefits of each of these options are discussed below.

When the surety elects to pay the damages, it provides the State transportation department with capital funds that the State transportation department would have had to obtain from its own sources, had the bond not been in place. The amount paid is based on the assumption that the financial benefit is equal to the costs to complete the project. However, the amount replaced may be less than the amount needed to complete the contract if a contractor has entered default partway through construction. Some possible reasons that the amount replaced is less than the amount needed include the following:

When a surety decides to assume the contractor’s responsibility and complete the contract, the State transportation department accrues the following two benefits:

It is assumed that, together, these benefits result in the completion of a defaulted contract approximately 60 days sooner than if a State transportation department had to complete the contract on its own. (It is estimated that the State transportation department would require a minimum of 60 days to re-bid the uncompleted portions of the contract.)

When the surety takes over a project, the construction contract does not have to be re-bid, and therefore, the contract price does not increase. Otherwise, the State transportation department would re-bid the project, which typically results in a higher price, because typically the original contractor had the lowest bid on the project. This benefit is assumed equal to the difference between the lowest bid and the second-lowest bid, which is estimated as 7 percent.

Defaults occur in the highway industry less the 1 percent of the time. The average default rate for five State transportation departments between 2008 and 2010 never reached 1 percent, instead ranging from 0.34 to 0.69 percent. This was further validated by default rates between 0 and 0.55 percent from five additional State transportation department case studies between 2007 and 2011. Therefore, the default benefit would be equal to the default rate multiplied by the total capital program value. In the following benefit-cost analysis, the highest default rate of 0.69 percent is used.

Based on the infrequency of defaults (less than 1 percent of the time), defaults are considered a statistically random event and cannot be attributed to any particular category of project. As a result, State transportation departments reported that the biggest benefit to a performance bond is the ability to improve a contractor’s performance by threatening to report poor performance to the surety. Reporting poor performance can impact the contractor’s ability to secure a future performance bond with that surety; therefore, it is an effective motivator.

The total costs of performance bonds that the State transportation department is ultimately responsible for are the performance bond premium, passed through by the contractor, and the State transportation department administrative costs associated with the management of performance bonds. Below is a discussion of the method used to calculate the total performance bond costs that are the responsibility of the State transportation department.

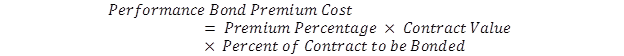

The performance bond premium cost results from the premium charged by the surety and the percent of the contract value that needs to be bonded, as shown in figure 6.

Figure 6. Equation. Performance bond premium calculation.

Determining a generalized cost of performance bonds is not a particularly straightforward task. The surety industry rates each contractor individually, in the context of a specific contract, and develops a separate premium for each individual project performance bond. Hence, it is nearly impossible to generalize or infer a specific cost for the bonding of a given project. Peurifoy and Oberlender provide the following guidance:(63)

The actual performance bond premium rate charged to a specific contractor accounts for the contract amount and project duration, as indicated above. The rate also varies based on a number of factors, mainly the contractor’s capacity to perform the work and its financial stability.

Table 15 lists the average performance bond costs in 2002, as provided by Peurifoy and Oberlender in their analysis of the subject, and shows bond costs as a range in cost in terms of dollars per $1,000 of project value. When these costs are translated to percentages of project value, the bond costs range from 0.65 to 1.2 percent for Heavy Civil projects.

Table 15. Representative costs of performance bonds per $1,000.(63)

Project Size |

Heavy Civil Projects |

First $500,000 |

$12.00 |

Next $2 million |

$7.50 |

Next $2,500,000 |

$5.75 |

Next $2,500,000 |

$5.25 |

> $7,500,000 |

$4.80 |

A portion of surety bond costs is fixed and does not decrease as the bonded amount decreases. Sureties’ costs are reflected in the bond premium, so that the premium, when expressed as a percentage of the amount bonded, will be larger for smaller bonds and smaller for larger bonds. This is reflected in the results of the outreach survey of prime highway contractors, which found that the price to secure performance bonds ranges from 0.22 to 2.5 percent of the contract amount, depending on the project’s size (see table 16 for details).

Table 16. Respondent contractor-reported bond rates.

Project Size |

Low (Percent) |

Average (Percent) |

High (Percent) |

Cost for project bond when bond < $100,000 |

0.22 |

1.06 |

2.5 |

Cost for project bond when bond $100,000-$1 million |

0.22 |

0.99 |

2.5 |

Cost for project bond when bond > $1 million-$10 million |

0.22 |

0.93 |

2.5 |

Cost for project bond when bond > $10 million-$50 million |

0.0976 |

0.70 |

0.85 |

Cost for project bond when bond > $50 million-$100 million |

0.475 |

0.52 |

0.85 |

Cost for project bond when bond > $100 million |

0.475 |

0.52 |

0.85 |

Overall Average |

0.79 |

||

Means Construction Cost Data (Means), a well-recognized source of construction costs for project estimations, provides percentage values for performance bond costs. In Means’ construction data book for heavy construction, the cost of bonds for highways and bridges is listed as a range from 0.4 to 0.93 percent of total contract value.(64) A thesis on the cost effectiveness of performance bonds, written by Lorena Myers of the University of Florida in 2009, collected State construction data from September 2007 to September 2009. As part of this study, the SFAA reported that the cost of performance bond premiums on projects typically ranged from 2 percent of total contract cost for small projects (i.e., those valued at less than $100,000) to 0.5 percent for very sizeable projects (i.e., those valued at more than $50 million. Table 17 shows one-time performance bond premiums for different ranges of contract amounts, as reported by the SFAA.

Table 17. State transportation departments construction performance bond rates.(11)

Contract Amount |

Performance Bond Premium |

Project Size Category |

Percent |

$100,000 |

$1,200-$2,500 |

< $1 million |

2.50 |

$1,000,000 |

$7,700-$13,500 |

$1 million-< $10 million |

1.35 |

$10,000,000 |

$56,950-$81,000 |

$10 million-< $50 million |

0.81 |

$50,000,000 |

$206,475-$341,000 |

> $50 million |

0.68 |

The surety industry is required to report data to regulators in all 50 States, which includes the number of performance bonds that are underwritten and the premiums paid for those bonds. Sureties report this data differently from State to State, so data can only be aggregated and used nationwide in an approximate fashion. With that caveat, it appears that in 2010 in the United States, the surety industry underwrote approximately $170 billion in construction contracts for bridges, highways, and airport runways issued by all levels of government, of which approximately $60 billion was for resurfacing contracts. The premiums for these bonds appear to have been priced at between $300 million and $350 million, which implies that the 2010 premium rate in this sector was approximately $2.25 per $1,000 of bond amount. Interviews conducted with surety company representatives suggest that such a premium is low by historical standards, so it is not used as the sole reference point in this review.

A point estimate, such as the one above, is a weighted average of a non-linear pricing structure, as illustrated in table 18 provided by the SFAA.4

Table 18. Non-linear premium structure in a typical bridge or highway performance bond.

Bonded Amount |

Total Premium |

First $500,000 |

$10.80 |

$500,000-$2,500,000 |

$6.70 |

$2,500,000-$5 million |

$5.30 |

$5 million-$7,500,000 |

$4.90 |

Above $7,500,000 |

$4.40 |

Because the performance bond premium rate is not linear, it is important to not use an overall average of all project sizes for the benefit-cost analysis. Also, there is minimal variability of the premium rates reported through different avenues; as such, the premium rates and project categories shown in table 16 are used for the benefit-cost analysis at the end of this chapter.

Based on data available online, the percent of the contract value required to be bonded varies from State to State, from 25 percent to 100 percent, depending on the size of the project. However, only six states do not require 100 percent contract value performance bond. When a project is larger than $500 million, the percent of contract value that requires a bond can change because it is difficult for a single company to acquire a performance bond of that amount. As a result, a 100 percent contract value is used in the benefit-cost analysis.

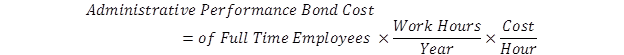

The administrative costs are the costs associated with the additional staffing required to manage the performance bond process. The calculation to find this number is shown in figure 7.

Figure 7. Equation. Administrative costs of performance bonds.

As reported by the five case study State transportation departments, the administrative staff required to manage the performance bonds process ranges between 0.5 full time employees and 1 full-time employee. Using the most costly option, one full-time employee at a fully burdened rate of $100/hour, the annual cost to administer the performance bonding process is $104,000. Due to the minimal cost compared to the premium cost of performance bonds, the annual cost to administer the process is not included in the overall cost of the performance bond process.

The default rate measures the frequency of the occurrence of defaults and is used to measure the risk of default. Default rate equals the number of defaults divided by the total number of projects. The actual default rate for the industry is not a published number. Also, using default data from a single year and/or from a single State transportation department does not account for any anomalies and can skew the data. Accordingly, the average default rate was determined based on project data from multiple states and multiple years available in literature, and on outreach efforts and case studies conducted during this investigation.

Myers’ thesis provided data for 19,135 construction projects for 30 States, shown in table 19.(11) Only six States reported contractor defaults between 2007 and 2009: Alabama, Georgia, Idaho, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Texas. For these States, there were a total of 10 defaulted contractors over 34 projects, while the rate of default was 0 for all other States. The total default rate for the entire 30 States is 0.19 percent. The second half of the data was collected as the recession hit the United States, which causes an expectation of a higher than normal default rate during this time frame. Even with the potential for a higher default rate, due to the recession, the default rate is only 0.19 percent. The bigger concern is hiring a contractor for many different jobs, which thereby impacts all jobs if the contractor defaults, as is evidenced by the fact that only 10 contractors defaulted during 34 different projects.

Table 19. State default rates.(11)

State |

Number of Defaults |

Total Projects |

Default Rate (Percent) |

Alabama |

7 |

631 |

1.1 |

Alaska |

0 |

187 |

0 |

Arizona |

0 |

205 |

0 |

Arkansas |

0 |

408 |

0 |

California |

0 |

1,237 |

0 |

Colorado |

0 |

326 |

0 |

Connecticut |

0 |

134 |

0 |

Delaware |

0 |

170 |

0 |

Georgia |

19 |

513 |

3.7 |

Hawaii |

0 |

129 |

0 |

Idaho |

2 |

188 |

1.06 |

Illinois |

0 |

2,682 |

0 |

Iowa |

0 |

1424 |

0 |

Kansas |

0 |

643 |

0 |

Maine |

0 |

545 |

0 |

Michigan |

0 |

1,303 |

0 |

Minnesota |

0 |

447 |

0 |

Mississippi |

2 |

392 |

0.51 |

Montana |

0 |

231 |

0 |

New Jersey |

0 |

256 |

0 |

New Mexico |

0 |

126 |

0 |

New York |

0 |

559 |

0 |

Ohio |

0 |

1,393 |

0 |

South Carolina |

6 |

681 |

0.88 |

South Dakota |

0 |

292 |

0 |

Texas |

1 |

1,333 |

0.075 |

Washington |

0 |

650 |

0 |

West Virginia |

0 |

945 |

0 |

Wisconsin |

0 |

901 |

0 |

Wyoming |

0 |

204 |

0 |

During the outreach effort conducted with State transportation departments, the average default rate between 2008 and 2010 of five of the responding State transportation departments never reached 1 percent, but instead ranged from 0.34 to 0.69 percent (see table 20 for details). The highest default rate, 0.69 percent, occurred in 2010, though the annual default rate increased from 2009’s rate at only two of the State transportation departments.

Table 20. Contractor respondent default rates (2008-2010).

Low |

Average |

High |

Total |

Default Rate (Percent) |

|

2010 Letting budget |

$150 |

$1,242 |

$2,507 |

$6,208 |

N/A |

Number of 2010 projects let |

100 |

378 |

604 |

1,891 |

0.69 |

Number of 2010 defaults |

0 |

3 |

7 |

13 |

|

Number of 2009 projects let |

150 |

408 |

628 |

2,038 |

0.34 |

Number of 2009 defaults |

0 |

2 |

3 |

7 |

|

Number of 2008 projects let |

100 |

337 |

633 |

1,684 |

0.36 |

Number of 2008 defaults |

0 |

2 |

4 |

6 |

|

Average |

0.46 |

||||

| Note: Includes Alabama, California, Florida, South Carolina, and Vermont. N/A = Not Applicable. |

Five case studies performed as part of this research gathered project data between 2007 and 2011. Of the five States, only one had a default that respondents could remember during this time frame. Again, the average default rate was less than 1 percent and ranged between 0 and 0.21 percent, as shown in table 21.

Table 21. State transportation department case study default rates (2007-2011).

State |

Number of Defaults |

Total Number of Projects |

Default Rate (Percent) |

Iowa |

0 |

3,980 |

0 |

Oklahoma |

0 |

974 |

0 |

Utah |

0 |

912 |

0 |

Virginia |

0 |

1,811 |

0 |

Washington |

1 |

481 |

0.21 |

Last, the surety industry underwrote approximately 85 percent of the bridge and highway construction that all levels of government undertook in 2010, but this represented only approximately 9 percent of the surety industry’s underwriting across all sectors. Similarly, public-sector bridge and highway construction accounted for only 15 percent of the construction sector’s $1.09 trillion output5 in the United States during 2010. The surety industry wrote $3.5 billion of performance bonds in that year, which, at an average premium of 0.64 percent, suggests that during a typical year, more than half of the construction efforts in the United States, both public and private, are covered by performance bonds.

As seen by the above data, defaults occur in the highway industry less than 1 percent of the time. Thus, defaults are considered a statistically random event that cannot be attributed to any particular category of project. In the following benefit-cost analysis, the highest average default rate of 0.69 percent is used to maximize the benefits of performance bonds.

The benefit-cost analysis of performance bonds is based on the above performance bond cost analysis and the performance bond benefit analysis. Because the performance bond cost varies by project size, the benefit-cost analysis has been conducted for five different project size categories. The cost of the performance bond is the contract value multiplied by the average performance bond premium percentage, as shown in figure 8.

![]()

Figure 8. Equation. Performance bond cost calculation.

Using the upper limit of each project size category, the associated performance bond costs are shown in table 22.

Table 22. Performance bond costs by project size.

Project Size |

Average Performance Bond (Percent) |

Performance Bond Cost |

< $100,000 |

1.06 |

$1,060 |

$100,000-$1 million |

0.99 |

$9,900 |

$1 million-$10 million |

0.93 |

$93,000 |

$10 million-$50 million |

0.70 |

$350,000 |

$50 million-$100 million |

0.52 |

$520,000 |

> $100 million |

0.52 |

$520,000 |

The most common remedy for a highway project construction default is for the surety to take over the project; this remedy also provides the highest benefit to the State transportation department. A default rate of 0.69 percent is used unilaterally in the benefit calculations because it was the highest average default rate identified by the research. The benefits result from the costs of default avoided by the State transportation department: expected cost of default, completion of contract at original cost, and completion of contract on schedule. The expected cost of default avoided by the State transportation department is equal to the default rate multiplied by the project value, shown in figure 9.

![]()

Figure 9. Equation. Avoided default cost calculation.

The avoided cost of re-bidding the defaulted contract is equal to the contract value multiplied by the default rate and the assumed increase in costs that result from a re-bid of 7 percent, shown in figure 10.

![]()

Figure 10. Equation. Avoided cost of re-bid calculation.

The avoided cost of additional delay due to default is equal to the days saved multiplied by the daily delay rate and the default rate, shown in figure 11. For projects less than $1 million, it was assumed that the delay would be 30 days at a daily rate of $1,000. Projects between $1 million and $10 million were assumed to have 60 days of delay at a daily rate of $5,000. Projects greater than $10 million were assumed to have 60 days of delay, at a daily rate of $10,000.

![]()

Figure 11. Equation. Avoided delay calculation.

The total benefit of a performance bond received by the State transportation department is equal to the sum of the above three benefits, shown in figure 12.

![]()

Figure 12. Equation. Total performance bond benefit calculation.

Table 23 provides assumptions for the performance bond benefit analysis. Table 24 uses the assumptions in table 23 to provide a summary of performance bond benefits and upper limit of the project size category for the contract value in the calculations.

Table 23. Assumptions for the performance bond benefit analysis.

Project Size |

Average Performance Bond Premium (Percent) |

Number of Days Saved |

Cost per Day Saved |

Cost to Re-bid (Percent of Contract) |

< $100,000 |

1.06 |

30 |

$1,000 |

7 |

$100,000-$1 million |

0.99 |

30 |

$1,000 |

7 |

$1 million-$10 million |

0.93 |

60 |

$5,000 |

7 |

$10 million-$50 million |

0.70 |

60 |

$10,000 |

7 |

$50 million-$100 million |

0.52 |

60 |

$10,000 |

7 |

> $100 million |

0.52 |

60 |

$10,000 |

7 |

Table 24. Performance bond benefits by project size.

Project Size |

Avoided Cost of Default |

Avoided Cost of Re-bid |

Avoided Schedule Delay Cost |

Total Benefit |

< $100,000 |

$690 |

$48 |

$207 |

$945 |

$100,000-$1 million |

$6,900 |

$483 |

$207 |

$7,590 |

$1 million-$10 million |

$69,000 |

$4,830 |

$2,070 |

$75,900 |

$10 million-$50 million |

$345,000 |

$24,150 |

$4,140 |

$373,290 |

$50 million-$100 million |

$690,000 |

$48,300 |

$4,140 |

$742,440 |

> $100 million |

$690,000 |

$48,300 |

$4,140 |

$742,440 |

The benefit-cost analysis included the calculation of the benefit-cost ratio. The benefit-cost ratio is equal to the performance bond benefit divided by the performance bond cost. A value greater than one indicates a net benefit to the State transportation department for performance bonds; a value less than one indicates a net cost to the State transportation department for performance bonds; and a value of one indicates there is no net cost or net benefit for the performance bond. The analysis required the following different elements to have assumed values: number of days the schedule is delayed as a result of a default; the cost per day of a schedule delay; the default rate; the cost to re-bid a project; and the contract value used in each project size category to calculate the benefit-cost ratio. However, the resulting benefit-cost ratio is heavily influenced by the assumptions made; should any of the assumption values change from the assumptions in table 23, the benefit-cost ratios will change. For each iteration of the analysis, table 25 shows which assumptions varied from the assumptions in table 23, as well as the resulting benefit-cost ratios.

Table 25. Performance bond benefit-cost ratio.

Project Size |

Benefit-cost ratios with varied assumptions |

|||

Original Assumptions from Table 23 |

Default Rate = 0.46 Percent |

Doubled the Number |

Lower Limit of Project Category for Contract Value |

|

< $100,000 |

0.89 |

0.59 |

1.08 |

2.65 |

$100,000-$1 million |

0.76 |

0.51 |

0.79 |

0.95 |

$1 million-$10 million |

0.82 |

0.54 |

0.84 |

1.02 |

$10 million-$50 million |

1.06 |

0.71 |

1.07 |

1.11 |

$50 million-$100 million |

1.42 |

0.95 |

1.43 |

1.44 |

> $100 million |

1.42 |

0.95 |

1.43 |

1.43 |

These analyses show that if the default rate is held constant at 0.69 percent, projects over approximately $10 million have a net benefit from performance bonds; projects between $100,000 and $1 million have a net cost for performance bonds; and projects less than $100,000 and between $1 million and $10 million vary between net cost and net benefit. However, when the default rate is lowered to 0.46 percent, the average default rate from table 20, the benefit-cost ratios are less than one for all project categories, indicating a net cost for performance bonds on all projects. For further details of this analysis, see appendix C.

2 Enterprise risk management is the consideration of uncertainty in all aspects of decisionmaking across the full span of an organization’s activities. All aspects of decisionmaking can be viewed from different perspectives, and the consideration of uncertainty should be evident from each of those perspectives. ISO 31000 defines six steps of enterprise risk management: 1. define goals and objectives in terms of risk and reward; 2. event identification; 3. risk assessment; 4. risk mitigation; 5. management controls; and 6. reporting.

3 The mean of the differences between the lowest bid and second-lowest bid in 128 contracts let in 2010 in Alabama, California, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, and Vermont was 7.3 percent. These 128 contracts were the subset of 642 contracts let in those states that were each over $1 million in value and were not repaving contracts. The mean difference for all 642 contracts was 8.7 percent and the mean difference for the subset of 292 contracts of all types over $1 million was 7.5 percent.

4 The SFAA is the designated statistical reporting agent for the surety and fidelity industries in all U.S. States, except Texas. In these 49 states, the association collects all of the data required by State insurance regulators from the industry.

5 U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Annual Industry Accounts, Gross Output by Industry.