U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

Federal Highway Administration Research and Technology

Coordinating, Developing, and Delivering Highway Transportation Innovations

| REPORT |

| This report is an archived publication and may contain dated technical, contact, and link information |

|

| Publication Number: FHWA-HRT-14-034 Date: August 2014 |

Publication Number: FHWA-HRT-14-034 Date: August 2014 |

This chapter presents the performance bond paradox. That paradox is that in spite of the fact that default rates are quite low, State transportation departments are unwilling to eliminate the performance bonds meant to deter or mitigate the effects of defaults. Subsections include State transportation department and contractor perspective on performance bond elimination, performance bonds’ ability to help State transportation departments select a competent contractor, bonding requirements, and project frequency. This chapter also contains a recommendation for raising the minimum project size that requires a performance bond.

During the outreach effort to the industry, 6 States responded to a State transportation department survey and 11 construction contractors responded to a separate contractor survey. One of the topics of the transportation survey was the concept of eliminating performance bonds and the overall satisfaction of the performance bond system’s ability to select a competent contractor.

VTrans and ALDOT noted that they would be very uncomfortable if performance bonds were eliminated. VTrans does not use risk management professionals because its projects are too small to justify their use, and no projects defaulted between 2008 and 2010 (out of approximately 350 total projects). The survey respondent from ALDOT was not sure whether his or her department had a risk management professional, nor could he or she provide project default information. The SCDOT respondent stated that he or she would be somewhat uncomfortable if performance bonds were eliminated. The South Carolina respondent did not know if SCDOT had a risk management professional and reported 14 defaults on more than 1,000 projects from 2008 to 2010.

Even when the rate of default was considerably lower, two State transportation departments still noted the same level of discomfort. Caltrans and FDOT reported that they are both somewhat uncomfortable eliminating performance bonds, despite the fact that both have risk management professionals on staff and that each only experienced six defaults between 2008 and 2010. (Caltrans completed over 1,800 projects and FDOT completed over 1,300 during this period.) See table 26 for more details. Additionally, the five State transportation department case studies found that none of the State transportation departments were willing to totally eliminate performance bonds from the prequalification process at this time.

Table 26. State transportation department respondent descriptive information.

State |

Prequalification |

Audit Prequalified Contractors |

Bonding Requirements |

Post-Project Contractor Performance Evaluation? |

Comfort Level if Performance Bonds are Eliminated |

Alabama |

Yes |

No |

Full coverage required |

No |

Very uncomfortable |

California |

No |

N/A |

Full coverage-flexibility for mega projects |

No |

Somewhat uncomfortable |

Florida |

Yes |

No |

Full coverage, but no bond for projects < $250,000 and only $250 million coverage for projects > $250 million |

Yes |

Somewhat uncomfortable |

Georgia |

Yes |

NR |

NR |

NR |

NR |

South Carolina |

Yes |

No |

Full coverage required |

Yes |

Somewhat uncomfortable |

Vermont |

Yes |

No |

Full coverage required |

Yes |

Very uncomfortable |

| N/A = Not Applicable. NR = No Response. |

These data suggest that smaller State transportation departments, as well as State transportation departments that do not closely track their contractor rates of default, may be most uncomfortable eliminating performance bonds. Irrespective of their default rates and risk management procedures, State transportation departments currently appear rather comfortably wedded to the use of performance bonds.

In NCHRP Synthesis 390, the 24 State transportation departments surveyed mostly expressed satisfaction with the current bonding system’s ability to identify competent construction contractors, as shown in table 27. In fact, only the Florida, New Mexico, and Oklahoma State transportation departments noted that they were dissatisfied with the current bond system.(17)

Florida has an extensive performance-based contractor prequalification system and has been using it for a number of years. (FDOT nonetheless reported being somewhat uncomfortable eliminating performance bonds.) It should be noted that ODOT-OK does not currently have a high number of qualified specialty contractors bidding on work.

Table 27. State transportation department satisfaction with current bond system.(17)

State Transportation Department |

Rated Satisfaction with Current Bond System |

State Transportation Department |

Rated Satisfaction with Current Bond System |

Arizona |

Satisfied |

New Hampshire |

Satisfied |

Arkansas |

Satisfied |

New Mexico |

Dissatisfied |

California |

Satisfied |

North Carolina |

Satisfied |

Colorado |

Satisfied |

Oklahoma |

Dissatisfied |

Connecticut |

Satisfied |

Pennsylvania |

Don’t know |

Florida |

Dissatisfied |

South Carolina |

Satisfied |

Louisiana |

Satisfied |

Texas |

Very satisfied |

Maine |

Very satisfied |

Utah |

Satisfied |

Maryland |

Satisfied |

Vermont |

Satisfied |

Massachusetts |

Satisfied |

Virginia |

Satisfied |

Nevada |

Satisfied |

Washington |

Satisfied |

Based on the responses to the contractor survey, most contractors did not believe that the ability to furnish performance bonds provided a guarantee of competence. A minority felt that performance bonds guaranteed that a State transportation department would award its work to qualified contractors, while most felt that a well-qualified contractor and a marginally qualified contractor who have the same bonding capacity did not compete on a level playing field. Responding contractors believed that well-qualified contractors are typically penalized when performance bonds are the primary (non-price-related) qualification for making a bid award. Based on the responses to the State transportation department survey, only one State transportation department felt similarly, while three State transportation departments felt that well-qualified contractors are not penalized through the use of performance bonds.

All responding contractors believed that the implementation of performance-based prequalification would eliminate some contractors from the bidding process, while only half expressed satisfaction with the current bonding company valuation process. Most contractors supported the idea that a fair system can be developed through the use of a performance-based system, which validates a similar finding in NCHRP Synthesis 390.(17)

Almost all responding contractors expressed confidence in the applicability of an objective and fair performance-based prequalification system, and most noted that they would support a performance-based system if it included an “appropriate” appeals component (see table 28 for details). All agreed that performance-based prequalification enables State transportation departments to select qualified contractors more readily than a selection process, without a prequalification step. Based on these findings, it seems that the construction industry would not be a barrier to the implementation of performance-based contractor prequalification.

Table 28. Respondent contractor views on methods of determining project qualification.

Please Indicate Your Level of Agreement with the Following Statement: |

Strongly Agree |

Agree |

Neutral |

Disagree |

Strongly Disagree |

“Performance bonds guarantee the State transportation department will award its work to a qualified contractor.” |

2 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

“A well-qualified contractor cannot compete on a level playing field with a marginally qualified contractor with the same bonding capacity.” |

5 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

“If eligibility to bid was based on satisfactory past project performance, some of my competitors would not be eligible to bid.” |

3 |

5 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

“I believe a performance-based prequalification system can be established that is reasonably objective and fair.” |

2 |

6 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

“I would support a performance-based system if there are appropriate appeal mechanisms.” |

2 |

5 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

Very Satisfied |

Satisfied |

Neither |

Dissatisfied |

Very Dissatisfied |

|

Please Indicate Your Level of Satisfaction with the Bonding Companies’ Valuation Process. |

0 |

5 |

4 |

0 |

1 |

The default rate for the industry is less than 1 percent, which indicates that it is a statistically random and infrequent event. State transportation departments protect themselves against potential financial losses from a default by requiring contractors to purchase performance bonds, though performance bonds have not been shown to have a causal relationship in default prevention. The SFAA reported that nationally, State transportation departments spent $300 million to $350 million in 2010 on performance bonds just for resurfacing projects to cover the less than 1 percent chance of a default. Additionally, 5 States spent $114,159,432 between 2007 and 2011 on performance bonds to be able to handle the financial burden of 2 defaults out of 8,158 projects, of which more than 50 percent were worth less than $1 million. However, when asked about abandoning the use of performance bonds, State transportation departments were very hesitant to do so. It appears that State transportation departments are not currently comfortable eliminating performance bonds. However, State transportation departments were more comfortable with the idea of possibly raising the minimum contract value that requires a performance bond.

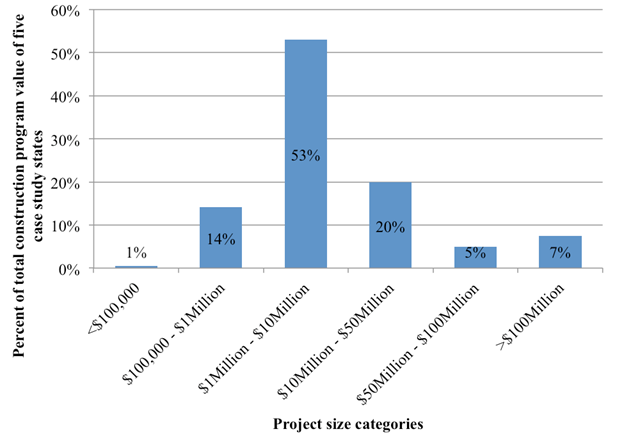

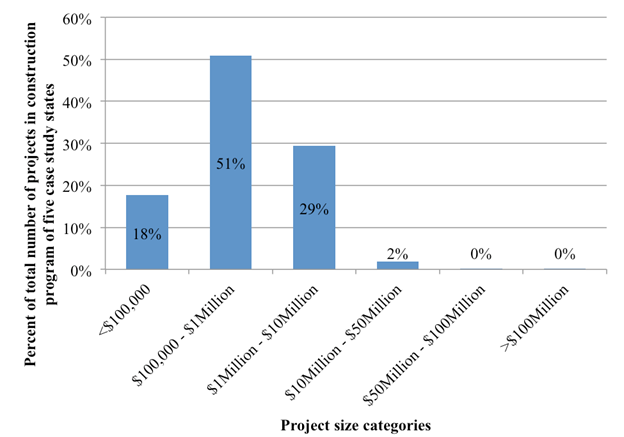

Project data from 2007 to 2011 was collected from five State transportation departments as part of the case studies performed during this investigation. Based on this actual project data, it was found that 68 percent of the construction program value was attributed to projects of $10 million or less, and 15 percent of the construction program value was attributed to projects of $1 million or less, as shown in figure 13. It was also found that 98 percent of the total number of projects in the construction program were less than $10 million in contract value, and 69 percent of the total number of projects in the construction program were less than $1 million, as shown in figure 14. There is no reason to suspect that this is not an accurate representation of the industry.

Figure 13. Graph. Percent of construction program based on total value in project category.

Figure 14. Graph. Percent of construction program based on number of projects in each project size category.

While most States do not accept the abandonment of performance bonds, several States did suggest that they would be interested in raising the minimum project value that requires a bond. Currently, the minimum project value that requires a bond varies between $0 and $300,000. Based on the previous benefit-cost analysis, projects with a contract value of less than $10 million tend to experience a net cost from performance bonds. Also, more than half of the projects in a State construction program, by value and by number, are worth less than $10 million, as shown in figure 13 and figure 14. Because of the sensitivity of the performance bond benefit-cost analysis to the assumptions, State transportation departments will most likely debate increasing the minimum project size that requires a bond. It is recommended that the minimum be somewhere between $1 million and $10 million.

The total cost savings of raising the floor of the minimum project size that requires a bond was calculated for each case study for the years 2007 through 2011. The total cost savings values were calculated by multiplying the total dollar amount for projects awarded under $100,000, between $100,000 and $1 million, and greater than $1 million to $10 million, by the associated average performance bond premium percentage, 1.06, 0.99, and 0.93 percent, respectively. The total savings that results from raising the performance bond floor to $1 million is the sum of the savings from projects under $100,000 and projects between $100,000 and $1 million between 2007 and 2011. The total savings that result from raising the performance bond floor to $10 million is the sum of the savings from projects under $100,000, projects between $100,000 and $1 million, and projects between $1 million and $10 million. Table 29 illustrates the amount of money each of the case study States could have saved between 2007 and 2011 if the minimum contract value that requires a bond was raised to between $1 million and $10 million.

Table 29. Five year cost savings from increase in minimum contract value that requires a performance bond.

State |

Savings if Performance Bond |

Savings if Performance Bond Minimum Raised to $10 Million |

Iowa |

$7,860,376 |

$26,361,418 |

Oklahoma |

$2,418,408 |

$12,673,639 |

Utah |

$1,986,490 |

$13,118,597 |

Virginia |

$4,843,811 |

$21,415,938 |

Washington |

$1,182,681 |

$6,517,335 |

While there is the ability to achieve considerable premium savings by raising the performance bond threshold, there remains a risk, albeit small, that a State transportation department will still experience a default. A State transportation department can further reduce the likelihood of default through the implementation of performance-based prequalification because it will help screen out poorer performing contractors. If a default does occur, the State transportation department still can recover funds from the contractor to offset the cost of default. Any unrecovered costs would be borne by the State transportation department, but as the above analysis indicates, large savings in bond premiums can significantly offset these costs.