U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

Federal Highway Administration Research and Technology

Coordinating, Developing, and Delivering Highway Transportation Innovations

| REPORT |

| This report is an archived publication and may contain dated technical, contact, and link information |

|

| Publication Number: FHWA-HRT-14-034 Date: August 2014 |

Publication Number: FHWA-HRT-14-034 Date: August 2014 |

This chapter presents a model for a performance-based contractor prequalification program, based on industry examples and literature. First is a discussion of the goals and requirements for the system, followed by the presentation of each of the three tiers of the model: administrative prequalification, performance-based prequalification, and project-specific prequalification. The program includes a quantitative method for modifying the contractor bidding capacity, based on the results of performance ratings.

The challenge in creating a model for performance-based prequalification is to achieve meaningful incentives for good performance and to encourage improvements to poor performance.(39) The model should not be too difficult to administer and the rating or evaluation of the contractor should be clear, tied to key project performance measures, transparent, and should include an appeals process that is perceived as fair and is fair. Also, each State has unique factors, such as geography, weather, demographics, and politics, which require that the model is adaptable to the needs and priorities of each State. The proposed performance-based contractor prequalification program considered the following four guiding principles for its development:

The proposed performance-based prequalification model combines elements of the processes used by IOWADOT, FDOT, ODOT-OH, and MTO, and borrows concepts and terminology from each. Additionally, NCHRP Synthesis 390 provides the basic foundation for the performance-based prequalification model in this chapter.(17) This approach, developed in the NCHRP Synthesis 390, is based on the study’s comprehensive literature review, including the survey responses recorded from 41 U.S. State transportation departments and 7 Canadian provincial ministries of transportation; a content analysis of solicitation documents from 35 State transportation departments; and interviews with 10 construction contractors, from firms that range in size from a local chip seal contractor to a major national Heavy Civil contractor.

The model proposed here consists of a two-tier process that is applicable to design-bid-build projects, and an optional third tier for project-specific qualification for DBB best value, DB, construction manager/general contractor, public-private partnerships, other alternate project delivery methods, and projects with specialized requirements. The following is a summary of the tiers:

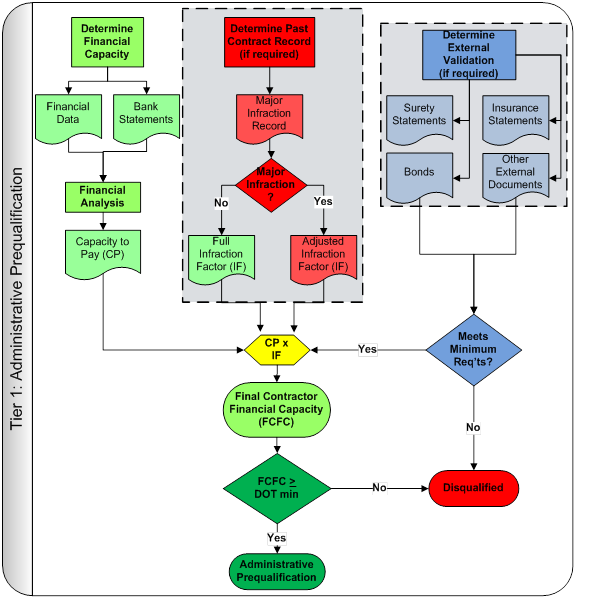

The first tier of the performance-based contractor prequalification model (shown in figure 15) consists of administrative prequalification (as defined in NCHRP Synthesis 390), which is already used, to varying degrees, by most State transportation departments. NCHRP Synthesis 390 defines administrative prequalification, as follows:(17)

A set of procedures and accompanying forms/documentation that must be followed by a construction contractor to qualify to submit bids on construction projects using traditional project delivery. These include evaluation of financial statements, dollar amount of work remaining under contract, available equipment and personnel, and previous work experience. This may be on a project-by-project basis or on a specified periodic basis.

Administrative prequalification consists of the following three components:

Figure 15. Chart. Tier one administrative prequalification.

The first aspect of tier one administrative prequalification is an evaluation of the contractor’s financial situation. At a minimum, a State transportation department should assess the financial positions of contractors for the following situations:

Administrative prequalification requires, at a minimum, that the contractor’s final contractor financial capacity is greater than or equal to a minimum requirement established by the State transportation department. The final contractor financial capacity is based on the contractor’s capacity to pay and on an infraction factor, based on the contractor’s past contract record with the State transportation department, as shown in figure 16. If a contractor’s resulting final contractor financial capacity does not at least meet the minimum State transportation department requirement, then the contractor is disqualified. External validation, such as surety statements, bonds, and insurance statements, can also be an added measure for administrative prequalification. When external validation is included, both the minimum external validation and minimum final contractor financial capacity requirements have to be met in order to gain administrative prequalification and move on to tier two performance-based prequalification.

![]()

Figure 16. Equation. Final contractor financial capacity calculation.

There are two steps required to calculate a contractor’s final contractor financial capacity:

To a contractor, payments to place a remedy for a contractual failure are an unexpected expense. The contractor’s liquidity is the most reliable indicator of its ability to make unexpected payments in the short run (i.e., without liquidating fixed assets or otherwise changing its capital structure). In the longer run (i.e., over periods of more than one year) the contractor’s solvency is indicated by its ability to withstand the variability of economic cycles and still be able to make unexpected payments. State transportation departments should satisfy themselves regarding the following:

A contractor’s liquidity is reflected in the value of assets that can be liquidated (i.e., converted into cash within 1 year) and made available for investment or spending. The amount by which these current assets exceed the value of the contractor’s corresponding current liabilities, and the amount of cash the contractor needs to retain as a minimum balance, are the amounts available to pay for a remedy for a contractual failure. Liquidity and solvency measures have been used in varying forms by the surety industry, FDOT, the IOWADOT, UDOT, ODOT-OH, and MTO as a basis for computation of a contractor’s bidding capacity. Specific to this model, the liquidity and solvency measures are used to calculate the capacity to pay.

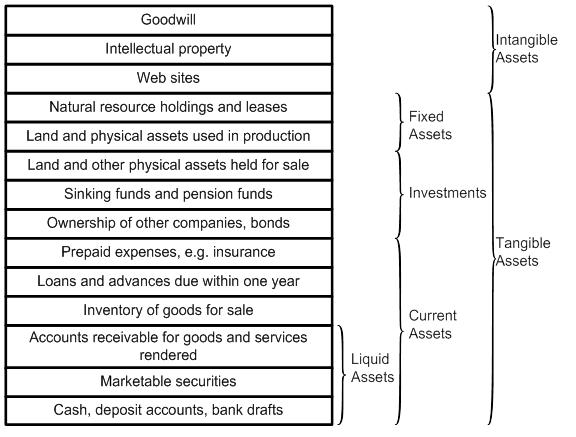

Generally accepted accounting principles classify all of a contractor’s assets according to their use in the delivery of services and how readily they can be turned into cash.

Figure 17. Graph. Classes of assets.

Assets that can be converted into cash within one year are current assets; liabilities that need to be retired within one year are current liabilities. Liquidity is the amount by which current assets exceed current liabilities (i.e., net current assets); in other words, the amount of cash that could be made available within one year to meet unexpected expenses, as shown in figure 18.

![]()

Figure 18. Equation. Liquidity calculation.

The liquidity of the contractor on the day that the contractor needs to make an unexpected payment to remedy a contract failure is what matters to a State transportation department. The agency cannot know that, however; all it can know is the liquidity of the contractor at the outset of the letting process. Months or years could elapse from the onset of the letting process to the date on which the contractor fails to meet its obligations.

The liquidity of a contractor can change significantly and quickly: a sudden downturn in work can result in rapid draw-downs of cash, as the contractor continues to pay the wages of key personnel, make long-term lease payments for heavy equipment, and service its debt. Energy and material prices, often fixed for the durations of construction contracts, can escalate suddenly and erase profit margins. The longer the duration of the contract, the less certain a State transportation department can be that the contractor’s liquidity will be as good towards the end of a contract as it was in the beginning.

Over periods longer than the one year that is defined for current assets and current liabilities, State transportation departments should look at the contractor’s ability to draw upon longer-term resources to maintain its liquidity in the face of deteriorating business conditions. The long-term ability is best indicated by the contractor’s solvency, or the contractor’s ability to draw upon its existing assets and its future income to meet its long-term obligations.7 In general terms, a firm with higher solvency can withstand more adverse economic conditions and still meet the basic test of survival: continued payment of its obligations. In the specific terms of paying for the remedy to a contract failure, a contractor with higher solvency is more likely to maintain sufficient liquidity through adverse economic conditions in order to make that unexpected payment.

The general measure of a contractor’s solvency is the extent to which its assets exceed its liabilities (i.e., equity), as shown in figure 19. This general measure indirectly includes income because all income retained by the contractor becomes part of and increases the contractor’s assets. For this reason, some of the specific measures of solvency deal with income separately from assets.

![]()

Figure 19. Equation. Solvency calculation.

The contractor’s capacity to pay that takes into account net current assets should be the basis of the capacity to pay on a short project that lasts up to 1 year. For longer projects, contractors can draw upon their equity to make payments; this is reflected in their capacity to pay. In figure 20, net current assets is the liquidity measure (current assets - current liabilities) and equity is the solvency measure (assets - liabilities). The equation also includes a weighting for the duration of the project; on a shorter-duration project, liquidity is more heavily weighted, while on a longer-duration project, solvency is more heavily weighted.

![]()

Figure 20. Equation. Capacity to pay calculation.

Where:

n equals the duration of the project expressed in years, with a minimum value of 1 year and a maximum value of 5 years.

Similar to what is currently practiced by some State and Federal agencies, the model includes a system for addressing major contract breaches or incidents. The system is modeled from the Ontario infraction system and is similar to the Florida Deficiency Letter. Both MTO and FDOT typically issue a warning, followed by an adverse contracting action if the contractor does not make the required corrections. If one or more major infractions are found, the contractor’s capacity to pay will be decreased according to the State transportation department’s published infraction factor scale, which is based on the severity of the specific infraction and the length of time since it occurred, which results in the final contractor financial capacity, as shown in figure 16.

At this time, a specific infraction factor scale is not proposed. However, the spectrum of results from the infraction factor scale could range from complete disqualification, due to a previous recent default, to a small capacity to pay reduction for an old contract, for which a warranty callback was ignored. FDOT has created an infraction factor scale, which could possibly be modified for individual State transportation department use. The length of time the contract record remains valid also needs to be resolved before the proposed model is implemented. In the industry, contract records currently remain on file anywhere from 3 years to an indefinite point in time. NCHRP Synthesis 390 found that agencies that conducted contractor performance evaluations generally kept evaluations for a minimum of 3 years.

As stated above, if the final contractor financial capacity meets or exceeds the State transportation department’s minimum financial requirements and the minimum external requirements are met, then the contractor moves on to tier two performance-based prequalification. Otherwise, the contractor is disqualified.

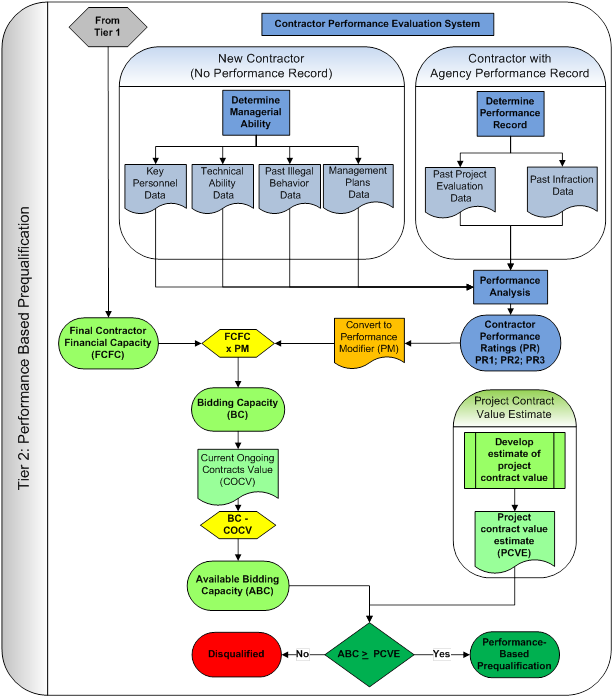

Tier two focuses on contractor performance and encompasses two primary areas: the determination of the contractor’s managerial ability and a post-project evaluation of performance on each contract. NCHRP Synthesis 390 defines performance-based prequalification in the following way:(17)

Performance-based prequalification, tier two, qualifies contractors to bid on a specific project, based on the contractor’s available bidding capacity. For a given project, the contractor’s available bidding capacity is its bidding capacity, based on the final contractor financial capacity from tier one and its past three years’ performance ratings, less the current ongoing contracts value, which is the value of work the contractor is currently committed to for all public and/or private owners with whom it has an active construction contract. Figure 21 graphically illustrates the mechanics of tier two.

A contractor is qualified if the resulting available bidding capacity value exceeds the project contract value estimate requirement established by the State transportation department for the given contract, which is equal to current engineer’s estimate for the project in question.

Figure 21. Chart. Tier two performance-based prequalification.

Contractors that are currently qualified and already have performance scores on contracts would be assigned a performance rating once a year, as is done in the Ontario system. The performance modifier is modeled after MTO’s method for determining a contractor’s overall performance score, which uses the contractor’s performance rating for the past three years, as determined by the agency’s performance-based contractor evaluation system. Figure 22 shows that the latest year’s average performance rating carries half the weight and the oldest year’s performance rating carries the least weight. This use of the last three years, with the heaviest weight on the most recent years, gradually reduces a year with an adverse rating’s impact to the point where, after three years, it disappears, in order to create an objective mathematical process to reward a marginal contractor who is committed to improving performance. The system contains a mechanism that skews the performance modifier from the past toward the present to forgive an uncharacteristic, yet well-deserved performance rating. The performance modifier is computed using the equation in figure 22.

![]()

Figure 22. Equation. Performance modifier calculation.

Where:

PR1 = average of all performance ratings for most recent year (year 1).

PR2 = average of all performance ratings for next most recent year (year 2).

PR3 = average of all performance ratings for oldest year (year 3).

New contractors that do not have performance records and that were administratively qualified in tier one would be assigned a starter performance modifier, based on an agency-determined set of factors that could include the following:

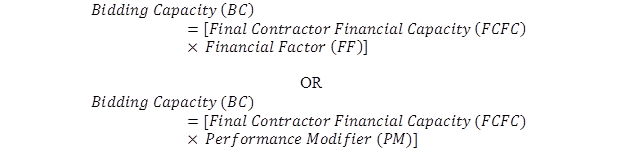

The computation of the contractor’s bidding capacity is deliberately modeled after the performance bonding paradigm, where the performance modifier replaces the surety evaluation of contractor default risk. The contractor’s bidding capacity is the maximum amount of work a given contractor can bid on if it has no other ongoing obligations, which is the product of the final contractor financial capacity and the performance modifier, as shown in figure 23.

The scale for a performance modifier varies from State to State, such as a 100-point scale, a 10-point scale, or a scale that uses 1 as average, with a maximum score of 1.5 and a minimum score of 0.5. In order to achieve a realistic bidding capacity, the final contractor financial capacity is multiplied by a financial factor that results from the performance modifier. In the surety world, the final contractor financial capacity is multiplied by a risk factor that varies between 5 and 10, whereas FDOT uses an ability factor between 5 and 15 to multiply the final contractor financial capacity. Depending on the performance modifier scale used by the State transportation department, the performance modifier can be used directly for the financial factor to compute the bidding capacity or the performance modifier can be converted to a financial factor.

Figure 23. Equation. Bidding capacity calculation.

At this point, the algorithm performs the same function that current systems in Iowa and Utah do; it reduces the amount of work a contractor can bid on, based on its past performance. To completely achieve the research goals, a process for rewarding contractors with superior records of performance is also needed. There are two viable alternatives to supply this function as follows:

In both options, the bidding capacity for a superior performer would be higher when using the performance-based prequalification model than it would when using the bonding capacity that results from the surety industry’s analysis.

The first alternative follows the same philosophy as the FDOT model that uses an ability factor, which essentially equates the financial factor, based on the performance modifier, to the multiplier of the final contractor financial capacity, which results in the bidding capacity of the contractor. Table 32 shows the proposed method for the first alternative, which allows the financial factor to range from 0 to 15 times the final contractor financial capacity, analogous to the FDOT system. Three performance ranges are established: green for superior performance, orange for above-average performance, and yellow for satisfactory performance. Because the green range includes the top performers, the surety would provide bonding up to 10 times the final contractor financial capacity. This system would allow the superior group to bid up to 15 times its final contractor financial capacity. The second group is the above-average performers, and the assumption was made that the surety industry would bond them at the average rate of 7.5 times the final contractor financial capacity. The upper end of this group would also have the incentive ability to bid more work that the surety supports. The last group would be the satisfactory group.

Table 32. Linking financial factor to performance alternative.

Financial |

Performance |

Financial |

Bidding |

Surety |

Incentive/Disincentive |

$950,000 |

100 |

15 |

$14,250,000 |

$9,500,000 |

$4,750,000 |

$950,000 |

97 |

14 |

$13,300,000 |

$9,500,000 |

$3,800,000 |

$950,000 |

95 |

13 |

$12,350,000 |

$9,500,000 |

$2,850,000 |

$950,000 |

93 |

12 |

$11,400,000 |

$9,500,000 |

$1,900,000 |

$950,000 |

91 |

11 |

$10,450,000 |

$9,500,000 |

$950,000 |

$950,000 |

89 |

10 |

$9,500,000 |

$7,125,000 |

$2,375,000 |

$950,000 |

87 |

9 |

$8,550,000 |

$7,125,000 |

$1,425,000 |

$950,000 |

84 |

8 |

$7,600,000 |

$7,125,000 |

$475,000 |

$950,000 |

82 |

7 |

$7,125,000 |

$7,125,000 |

$0 |

$950,000 |

80 |

6 |

$7,125,000 |

$7,125,000 |

$0 |

$950,000 |

65-79 |

5 |

$4,750,000 |

$4,750,000 |

$0 |

$950,000 |

64 |

5 |

$3,707,317 |

$4,750,000 |

($1,042,683) |

$950,000 |

60 |

5 |

$3,475,610 |

$4,750,000 |

($1,274,390) |

$950,000 |

56 |

5 |

$3,243,902 |

$4,750,000 |

($1,506,098) |

$950,000 |

50 |

5 |

$2,896,341 |

$4,750,000 |

($1,853,659) |

The second alternative assumes an output from the tier two contractor performance evaluation system that yields the performance modifiers shown in table 33. Rather than three groups of contractors, as above, there are two. The average contractor’s performance modifier is equal to one. A performance modifier above 1.00 permits a contractor to bid on more work than it could if its bidding capacity equaled its surety-developed bonding capacity. The reverse is true if it is below 1.00.

Table 33. Alternative performance modifier system.

Financial |

Performance |

Financial |

Bidding |

Surety |

Incentive Extra |

$950,000 |

1.45 |

7.5 |

$10,331,250 |

$7,125,000 |

$3,206,250 |

$950,000 |

1.40 |

7.5 |

$9,975,000 |

$7,125,000 |

$2,850,000 |

$950,000 |

1.35 |

7.5 |

$9,618,750 |

$7,125,000 |

$2,493,750 |

$950,000 |

1.30 |

7.5 |

$9,262,500 |

$7,125,000 |

$2,137,500 |

$950,000 |

1.25 |

7.5 |

$8,906,250 |

$7,125,000 |

$1,781,250 |

$950,000 |

1.20 |

7.5 |

$8,550,000 |

$7,125,000 |

$1,425,000 |

$950,000 |

1.15 |

7.5 |

$8,193,750 |

$7,125,000 |

$1,068,750 |

$950,000 |

1.10 |

7.5 |

$7,837,500 |

$7,125,000 |

$712,500 |

$950,000 |

1.05 |

7.5 |

$7,481,250 |

$7,125,000 |

$356,250 |

$950,000 |

1.00 |

7.5 |

$7,125,000 |

$7,125,000 |

$0 |

$950,000 |

0.95 |

7.5 |

$6,768,750 |

$7,125,000 |

($356,250) |

$950,000 |

0.90 |

7.5 |

$6,412,500 |

$7,125,000 |

($712,500) |

$950,000 |

0.85 |

7.5 |

$6,056,250 |

$7,125,000 |

($1,068,750) |

$950,000 |

0.80 |

7.5 |

$5,700,000 |

$7,125,000 |

($1,425,000) |

$950,000 |

0.75 |

7.5 |

$5,343,750 |

$7,125,000 |

($1,781,250) |

Before each letting, the State transportation department would require each bidder to disclose its current ongoing contracts value. The State transportation department would then subtract that amount from each contractor’s bidding capacity to find the available bidding capacity, as shown in figure 24. If the available bidding capacity was greater than the contractor’s bid amount, it would be considered a responsible bidder, and if it had the low bid, it could then be awarded the contract. If the available bidding capacity was less than the contractor’s bid amount, the agency would declare the contractor non-responsible for this particular project only and reject its bid. This would permit that contractor to remain eligible to continue to bid on projects that did not exceed its available bidding capacity. Thus, the marginal contractor is not debarred. The agency is merely limiting the risk it will take on continued marginal or unsatisfactory performance on future projects.

![]()

Figure 24. Equation. Available bidding capacity calculation.

The State transportation department develops a project contract value estimate for the project in question from the current engineer’s estimate. This value will either equal the engineer’s estimate or be increased by an amount to account for market conditions. In order to acquire a tier two performance-based prequalification, the contractor’s available bidding capacity value needs to equal or exceed the project contract value estimate requirement for the given contract, which is equal to the estimated value of the contract that will be completed in a single fiscal year or equal to the highest estimated fiscal-year expenditure on a project that will take multiple years to complete. If the contractor’s available bidding capacity is not at a minimum equal to the project contract value estimate, then the contractor is disqualified; otherwise, the contractor is prequalified, so long as there is not a project-specific prequalification required on the project. If there is a project-specific prequalification, then the contractor advances to the tier three project-specific prequalification process.

Below are three scenarios that illustrate how the first and second tiers of the proposed model would work.

A new contractor with excellent supporting documents, recommendations, and an excellent technical score would have its available bidding capacity determined as follows:

Table 34. Contractor prequalification scenario A, tier one.

Tier One |

|

Capacity to Pay (CP) = |

$2.7 million |

Final Contractor Financial Capacity (FCFC) = |

$2.7 million |

Minimum Final Contractor Financial Capacity = |

$500,000 |

$2.7 million > $500,000; therefore, this contractor is administratively prequalified.

Since this is a new contractor, no major infractions could have been incurred, so its capacity to pay becomes its final contractor financial capacity. Since the contractor exceeds the minimum final contractor financial capacity, it meets the tier one qualification.

Table 35. Contractor prequalification scenario A, tier two.

Tier Two |

|

Managerial Ability Evaluation for New Entrant (performance modifier) = |

75 |

Minimum Performance Modifier = |

65 |

New Contractor Financial Factor (FF) = |

1.0 |

Bidding Capacity (BC) = |

Final Contractor Financial Capacity (Financial Factor) = $2.7 million (1.0) = $2.7 million |

Current Ongoing Contracts Value (COCV) = |

$1.1 million |

Available Bidding Capacity (ABC) = |

$1.6 million |

Project Contract Value Estimate = |

$1 million |

$1.6 million > $1 million; therefore, this contractor is performance-based prequalified.

The new contractor in Scenario A is evaluated based on its key personnel, technical ability, past illegal activity, and management plans. Based on these factors, the contractor is assigned a performance modifier of 75, which would likely exceed the minimum score (for the purposes of this example, assume FDOT’s minimum score of 65). The new contractor would not be eligible for a financial factor increase, but since its available bidding capacity is greater than the project contract value estimate, it would still be qualified to submit a bid and to start building a performance record with the State transportation department.

This scenario is for an existing contractor that incurred one minor infraction for removing concrete for a bridge barrier wall and allowing broken concrete to fall into sensitive wetland. A 20 percent sanction on its capacity to pay was imposed as a result. The contractor’s annual performance rating is also low, due mostly to insufficient onsite supervision on several projects. Based on these factors, the contractor’s available bidding capacity does not meet the minimum project contract value estimate, due to the fact that the contractor was not able to receive a financial factor greater than one, due to the low performance modifier.

Table 36. Contractor prequalification scenario B, tier one.

Tier One |

|

Capacity to Pay (CP) = |

$22 million |

Final Contractor Financial Capacity (FCFC) = |

$17.6 million (applying 20 percent infraction) |

Minimum Final Contractor Financial Capacity = |

$500,000 |

$17.6 million > $500,000; therefore, this contractor is administratively prequalified.

Table 37. Contractor prequalification scenario B, tier two.

Tier Two |

|

Performance Modifier (PM) = |

55 |

Minimum Performance Modifier = |

65 |

Contractor Financial Factor (FF) = |

1.0 |

Bidding Capacity (BC)= |

Final Contractor Financial Capacity (Financial Factor) = $17.6 million (1.0) = $17.6 million |

Bidding Capacity (BC)= |

$17.6 million |

Current Ongoing Contracts Value (COCV = |

$14.1 million |

Available Bidding Capacity (ABC) = |

$3.5 million |

Project Contract Value Estimate = |

$5.5 million |

$3.5 million < $5.5 million; therefore, this contractor is disqualified.

This contractor would normally seek a contract that is the size and nature of the contract in Scenario B. The contractor meets the tier one qualification requirements. However, after factoring its infraction, the contractor only has $17.6 million of capacity to pay remaining. Under tier two of the performance evaluation, it fails to meet the minimum performance modifier needed to obtain a financial factor greater than 1.0, which results in an available bidding capacity of $3.5 million. The project requires that the available bidding capacity is at least $5.5 million in order to qualify to bid on the project, and therefore, this contractor is not qualified to bid. Had the contractor put more focus on its performance, it may have been eligible for a performance modifier increase, which could have offset the reductions from the infraction and workload.

In this scenario, an existing contractor has invested heavily in staff training on safety and environmental topics, as well as in project management and team-building skills. The contractor is approximately the same size as the one in Scenario B and wants to bid on the same project. The contractor has had considerable bidding success lately and has a significant amount of work on the books. The State transportation department appreciates the contractor’s professional conduct and cooperative project approach, and because of this, the contractor has received excellent evaluations on most of their agency projects. The contractor’s Performance Modifier corresponds to a financial factor of 10.0 and it has not incurred an infraction on any of its projects in numerous years.

Table 38. Contractor prequalification scenario C, tier one.

Tier One |

|

Contractor Capacity to Pay (CP) = |

$21 million |

Infraction Factor = |

1 |

Final Contractor Financial Capacity (FCFC) = |

$21 million |

Minimum Final Contractor Financial Capacity = |

$500,000 |

$21 million > $500,000; therefore, this contractor is administratively prequalified.

Table 39. Contractor prequalification scenario C, tier two.

Tier Two |

|

Performance Modifier (PM) = |

89 |

DOT Minimum Performance Modifier = |

65 |

Contractor Financial Factor (FF) = |

10.0 |

Bidding Capacity (BC) = |

Final Contractor Financial Capacity (Financial Factor) = $21 million (10) = $21 million |

Contractor Bidding Capacity (BC) = |

$210 million |

Current Ongoing Contracts Value (COCV) = |

$180 million |

Contractor Available Bidding Capacity (ABC) = |

$30 million |

Project Contract Value Estimate = |

$5.5 million |

$30 million> $5.5 million; therefore, this contractor is performance-based prequalified.

Since the contractor in Scenario C has not incurred any major infractions, their capacity to pay becomes their final contractor financial capacity, and because they exceed the minimum final contractor financial capacity, they meet the tier one qualification requirements. In addition, this contractor’s performance modifier corresponds to a financial factor of 10.0; as a result, their bidding capacity rises from $21 million to $210 million. The contractor has an available bidding capacity greater than the project contract value estimate and therefore qualifies to submit a bid. Even though this contractor would have initially been disqualified, due to insufficient capacity to pay, their consistently strong performance enables them to qualify in spite of the high value of their ongoing contracts. This performance level could have a similar positive impact in the case of an infraction that was incurred from one isolated incident.

Tier three, detailed in figure 25, is a project-specific prequalification tier that is designed to closely evaluate a contractor’s qualifications and experience in terms of the specific needs of a given project. NCHRP Synthesis 390 defines project-specific prequalification in the following way:(17)

This final tier is an optional portion of the prequalification process and is intended for use only on projects delivered by alternative project delivery methods and/or on projects that have specific requirements, such as experience. For instance, a design-bid-build project for the seismic retrofit of a major bridge requires a contractor that has some level of specific technical experience in order to mitigate the risks to quality and service life. The project-specific prequalification for this hypothetical project could be as simple as restricting competition to only those contractors that can show documented, relevant experience. At the other extreme, a design-build project estimated to cost hundreds of millions of dollars may require a complex evaluation of contractor qualifications and past experience in order to short-list the best-qualified design-build teams before they evaluate pricing information.

Figure 25. Chart. Tier three project-specific prequalification.

The following scenario illustrates how the model will typically operate. A State transportation department has determined that project-specific prequalification is required for a mechanically stabilized earth wall system that will need to be much higher than the State’s previously built mechanically stabilized earth walls. Six contractors are competing. Five of the six contractors have identical financial capacity and work experience, but have different performance records. The sixth contractor is a smaller firm with an exceptional track record. The agency has a minimum financial capacity rating of $1 million to be administratively prequalified for this class of work. Table 40 shows how the tier one operates for this particular scenario.

Table 40. Tier one administrative prequalification example scenario.

Tier One—Administrative Prequalification |

||||||

Contractor |

Capacity to Pay |

Major Infraction Record |

External Validation |

Major Infraction Adjustment (Percent) |

Final Contractor Financial Capacity |

Administrative Prequalification? |

A |

$12 million |

0 |

Ok |

100 |

$12 million |

Yes |

B |

$12 million |

Warranty deficiency |

Ok |

95 |

$11.4 million |

Yes |

C |

$12 million |

0 |

Ok |

100 |

$12 million |

Yes |

D |

$12 million |

0 |

Ok |

100 |

$12 million |

Yes |

E |

$12 million |

Two cure notices in past 2 years |

Ok |

50 |

$6 million |

Yes |

F |

$8 million |

0 |

Ok |

100 |

$8 million |

Yes |

From table 40, all six interested contractors are administratively qualified to proceed to tier two, where their past performance will be factored into the qualification to bid on this specific project. The following are the tier two assumptions for this example:

The engineer’s estimate for the given project is $28 million. By statute, the agency is allowed to award a project at 8 percent over the engineer’s estimate at the time of the letting. Therefore, the project contract value estimate = 1.08 x $28 million = $30 million.

Contractor performance modifier and financial factors are set using table 40.

Table 41 shows the outcome of the tier two prequalification calculations. Two contractors were eliminated from the bidding because their performance reduced the amount of work that they could continue to bid. If contractor B would have raised its performance rating to an 82, it would have been allowed to bid. Contractor E’s dismal performance record, combined with its infraction history, was also eliminated, even though its current financial position was equal to that of contractors A through D. Without the performance-based prequalification program, contractor E could conservatively have gotten a performance bond for five times its capacity to pay ($60 million) less its current ongoing contracts value ($30 million). This would have been $30 million and it would have been allowed to bid on this project.

Table 41. Tier two performance-based prequalification example scenario.

Tier Two—Performance-Based Prequalification |

|||||||

Contractor |

Final Contractor Financial Capacity |

Performance Modifier |

Financial Factor |

Bidding Capacity |

Current Ongoing Contracts Value |

Available Bidding Capacity |

Performance-Based Prequalification? |

A |

$12 million |

88 |

9.5 |

$120 million |

$80 million |

$34 million |

Yes |

B |

$11.4 million |

75 |

5 |

$57 million |

$40 million |

$17 million |

No |

C |

$12 million |

84 |

8 |

$96 million |

$40 million |

$56 million |

Yes |

D |

$12 million |

80 |

6 |

$72 million |

$40 million |

$32 million |

Yes |

E |

$6 million |

56 |

5 |

$30 million |

$30 million |

$0 |

No |

F |

$8 million |

97 |

14 |

$112 million |

$20 million |

$92 million |

Yes |

| Note: Performance modifier and financial factor from table 40. |

The State transportation department uses a two-envelope system similar to the one used by the NSW Department of Commerce in Australia. This system requires that bidders submit a sealed envelope that contains their project-specific qualification data and a second sealed envelope that contains a responsive bid. The first envelopes are opened publicly and the qualification data in them is then compared to the prequalification criteria. The second envelopes of those unqualified bidders are returned to the bidders unopened and are declared nonresponsive. The remaining bid envelopes are then opened and the contract is awarded to the lowest responsive bidder. The State transportation department establishes the following three evaluation criteria for project-specific prequalification, as follows:

The contractor shall have built a minimum of five mechanically stabilized earth (MSE) walls in excess of x meters high and y meters long.

The contractor shall assign the general superintendent from at least one of the relevant projects listed in the qualifications identified for the project at hand.

The contractor shall have no minor safety infractions for projects that are completed or ongoing in the 12 months that proceed the date the bids are due. Table 42 shows the details of this scenario.

Table 42 shows the outcome, based on the results of the previous two tiers.

Table 42. Tier three project-specific prequalification example scenario.

Tier Three—Project-Specific Prequalification |

|||||||||

Contractor |

Project-Specific Prequalification Criteria |

Meet all prequalification criteria? |

Hypothetical Bid Amount |

Responsive/ Responsible? |

Final Result |

||||

Number of MSE wall projects completed (min of 5) |

Is the superintendent from a qualifying MSE project? |

Any minor safety infractions over past 12 months? (max of 0) |

|||||||

A |

6 |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

$31,400,000 |

Yes |

|||

B |

Excluded in tier two |

||||||||

C |

5 |

No |

No |

No |

$30,800,000 |

Excluded |

|||

D |

5 |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

$33,500,000 |

Yes |

|||

E |

Excluded in tier two |

||||||||

F |

8 |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

$29,350,000 |

Yes |

Winner |

||

The literature on performance-based prequalification devotes a significant amount of attention to evaluating the barriers and challenges to implementing a performance-based contractor prequalification system. (See references 1, 2, 17, 35, and 37.) Ultimately, the various analyses reviewed in this study noted very few significant barriers to the implementation of a performance-based contractor prequalification. Many State transportation departments already have some form of contractor evaluation included in their bid process; many have some form of performance-based prequalification included as well. Based on input provided by the contractor surveys and collected in the literature, contractors seem to welcome implementation of this approach as a tool to reduce or remove the number of marginally qualified contractors against whom they need to compete. Nevertheless, NCHRP Web Document 38 notes that the following implementation issues will need to be addressed when introducing a performance-based prequalification process, as follows:(1)

Integration with existing construction administration systems, such as Site Manager.

Qualifications of the evaluators to consider.

Evaluation process administrative rules.

Frequency of evaluations.

Appeals process development.

Lifespan of evaluations/duration of disqualification.

Impact on contractor bonding.

Legal implications.

Of the potential barriers listed above, significant focus should be placed on the implementation of administrative rules for the evaluation process.(2) The agency will need to ensure that its evaluators are indeed qualified to evaluate the subject contractors. In most cases, contractors should be evaluated by the agency construction personnel who administer the evaluated contract. Implementation will require that an ongoing training program for the evaluators be developed and implemented to ensure consistency between evaluators and across different types of projects. This component of the program will also be necessary to demonstrate the agency’s commitment to fairness and to ensure the reduction of as much subjectivity in the process as possible. Agencies that currently use this type of system (such as FHWA and FDOT) have found that a review of all contractor evaluations one level above the “evaluator” is also required to make the program as consistent as possible.(31,33) This issue was highlighted in NCHRP Synthesis 390, in which 8 out of 10 interviewed contractors indicated that their major concern with performance-based prequalification is the agencies’ ability to rate them consistently from project to project.(17)

The administrative rules of the process also need to be transparent and logically derived.(28) It is important to determine the frequency of evaluations. The literature on this topic seems to support at least one interim evaluation provided to the contractor before the final evaluation. (See references 31, 32, 33, and 34.) FDOT furnishes evaluations on a monthly basis. The crucial element will be to notify the contractor when it is not performing well and to provide it with the opportunity to correct its deficiencies and shortcomings before negative evaluations become part of its permanent record. There is a need for an appeals process, whereby the contractor can refute an unfavorable rating, which provides the contractor with due process before it is penalized by the evaluator.

The question of the appropriate length of an evaluation’s life span also needs to be addressed because it is an integral component of the evaluation process. NCHRP Synthesis 390 found that the majority (73 percent) of its survey respondents maintained evaluations in their active record for at least 3 years.(17) Survey results also support this time interval, and literature on the subject recommends a “rolling [3]-year average.”(2,34) This selected duration creates an incentive for contractors to perform in a satisfactory manner, since a bad evaluation could impact the work they can secure for a 3-year period. The amount of time a contractor can remain disqualified, due to certain behavior, may be longer. Those that lose their qualification because of criminal acts are usually debarred from participation indefinitely. In contrast, those contractors that are disqualified for marginal performance, usually because they default on a contract, are able to regain their qualification after they prove to the agency that they have corrected the problems that caused the default(s).

In addition to the literature review, the topic of acceptance for implementation of performance-based prequalification was tackled during the outreach surveys with both the State transportation departments and the contractors. All responding contractors believed that implementing performance-based prequalification would eliminate some contractors from the bidding process, while only half expressed satisfaction with the current bonding company valuation process. Most contractors supported the idea that a fair system can be developed through the use of a performance-based system, which validates a similar finding in NCHRP Synthesis 390.(17)

Almost all responding contractors expressed confidence in the applicability of an “objective and fair” performance-based prequalification system and most noted that they would support a performance-based system if it included an “appropriate” appeals component (see table 13 for details). All agreed that performance-based prequalification enables agencies to select qualified contractors more readily than does a selection process that does not have a prequalification step. Based on these findings, it seems that the construction industry would not be a barrier to the implementation of performance-based contractor prequalification.

The State transportation departments had more mixed attitudes toward performance-based prequalification. None of the State transportation departments agreed that performance bonds guarantee that a State transportation department will award work to qualified contractors, and three out of five disagreed with the statement. Three State transportation departments felt that using a performance-based prequalification process can assist with the selection of more qualified contractors. One State transportation department that currently uses performance-based prequalification indicated that the process provides its agency with “more assurance that contractors bidding on the work have experience, financial resources, and equipment necessary to perform the work.”

When asked if contractors would be receptive to the implementation of performance-based prequalification, two out of three State transportation department respondents, whose agencies do not currently use performance-based prequalification, said they felt contractors would not welcome the change. This perception stands in marked contrast to the overwhelmingly positive feedback that contractors provided about the change. State transportation department respondents otherwise felt that agency members, the bonding industry, general public, and legislators would either be neutral to or would welcome the implementation of performance-based prequalification (see table 43 for response rates).8

Table 43. Respondent State transportation department views on stakeholder willingness to adopt performance-based prequalification.

Willingness to Use Performance-Based Prequalification |

Would Actively Work to Institute the Change |

Would Welcome the Change |

Would Be Neutral to the Change |

Would Not Welcome the Change |

Would |

Agency members |

0 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

Contractors that bid agency work |

0 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

The bonding industry |

0 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

The general public |

0 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

Legislators |

0 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

Interestingly, when representatives of the agencies that do not use performance-based prequalification were asked what the greatest barrier to the implementation of performance-based contractor prequalification would be, no two respondents identified the same obstacle. One cited construction industry opposition; one cited a lack of agency resources to expand the program; one cited a fear of legal repercussions associated with unfavorable decisions made during a performance-rating process; and one cited the belief that it cannot be implemented in a “fair and equitable” manner.

The results of the outreach surveys with the State transportation departments and contractors reinforce the NCHRP Synthesis 390 conclusion that barriers to performance-based prequalification implementation are low among members of the construction industry and that, while State transportation departments show little willingness to completely abandon performance bonds, they acknowledge the potential benefits of evaluating contractor project performance and entering it in the prequalification process.

7 Interest payments on debt, the final principal payment on debt, lease payments, and any other fixed obligations.

8 State transportation department respondents noted that their agency’s control over making changes to prequalification practices extended to changes to administrative rules (provided the rules still followed the applicable legislation) and their ability to influence changes to legislation.