U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

Federal Highway Administration Research and Technology

Coordinating, Developing, and Delivering Highway Transportation Innovations

| REPORT |

| This report is an archived publication and may contain dated technical, contact, and link information |

|

| Publication Number: FHWA-HRT-14-034 Date: August 2014 |

Publication Number: FHWA-HRT-14-034 Date: August 2014 |

Agency name: Iowa Department of Transportation (IOWADOT)

Delivery method(s) the organization is allowed to use:

Does the agency use performance-based prequalification in any form? Yes.

Which projects require performance bonding? All projects.

What is the value of the performance bonds required for projects? 100 percent of construction cost.

Agency's prequalification process

IOWADOT has an annual prequalification program based on a review of the contractor’s financials, experience, and equipment, and it places the heaviest weight on a contractor’s work performance, organizational management, and safety. Contractors need to prequalify for specific types of work and there are minimum financial requirements for larger projects. The current system has been in place for the past 30 years. The management and implementation of the prequalification program requires half the time of one technician (1,040 hours). The size, type, and/or complexity of a project does not change the effort required to prequalify.

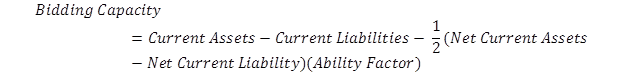

Once prequalified, IOWADOT calculates the bidding capacity of each contractor, based on the company’s financials and past performance evaluations as shown in figure 26. The ability factor (AF) is calculated from the most recent 30 project performance evaluations, which is used in figure 27. If a contractor has no previous IOWADOT performance evaluations, an average project performance score (APPS) of 50 is assigned. The current program has APPSs for contractors that range between 12.5 and 80.0 on a 100-point scale.

Figure 26. Equation. Contractor bidding capacity calculation.

Figure 27. Equation. Ability factor calculation

The contractor project performance evaluations are done at the completion of every project. The contractor receives a copy of the completed performance evaluation. If the evaluation is negative, the contractor does not have to be informed prior to submittal of the performance evaluation. IOWADOT does not have an appeals process in place for a contractor that receives a negative project performance evaluation. A negative project performance evaluation does not automatically disqualify a contractor from future work. However, a negative performance evaluation does impact the bidding capacity of a contractor because it also negatively impacts the AF. All performance evaluations remain on the record indefinitely. Because the performance evaluation system has been in place for 30 years, IOWADOT does not have any other experiences to compare the existing performance evaluations system to. As a result, IOWADOT cannot identify the impact performance has had on the overall success of projects.

One effective practice that IOWADOT employs is to send out a letter of commendation to the top 15 contractors in the State on an annual basis. This letter turns into a marketing instrument for those contractors and stimulates competition within the contracting community to become part of the IOWADOT top 15 firms. A challenge for the current performance evaluation program is that there is poor calibration between individual IOWADOT raters; the final evaluation score varies, due to variance in how different IOWADOT staff evaluates the performance. Additionally, if a contractor owns significant assets, its ability factor could drop very low and it would still be able to bid.

Agency’s experience with performance bonding and sureties

IOWADOT requires all projects to have a performance bond valued at 100 percent of the construction cost.

In the past 24 years, IOWADOT has implemented approximately 24,000 contracts and has only had to call in a surety 12 times, and only 1 of those resulted in a default. When the default occurred, there was a 4 to 6 week delay in the project. However, if this delay had occurred later in the construction season, the delay would have had a much larger impact. To resolve the default, the surety asked that the project be re-let to a different contractor and then paid the difference over the original contract.

IOWADOT remembered the specifics of three other situations where assistance from the surety was required. In these three occasions, the contractors asked to be released from their contracts because of reasons unrelated to their performance. Two decided to not invest in specialty equipment upgrades, which were required for their contracts, and the third decided to concentrate all their business in a neighboring State with a bigger construction budget. On all three occasions, IOWADOT got the surety involved and agreed to re-let the contracts with the surety to pay the difference between the original amount and the low re-bid. On two of those projects, IOWADOT got the projects for less than the original amount and refunded the difference in the bond to the surety. IOWADOT has never had a surety inform them of a performance issue or become involved in a project without an agency’s request.

IOWADOT received a monetary payment to satisfy the performance bond for the project that defaulted. IOWADOT has never had a dispute with any performance bond surety about sufficient compensation for a performance bond. In IOWADOT’s experience, 99 percent of the time a surety is informed of a performance issue, the surety does not become involved and the project does not default. The other 1 percent of the time, the surety becomes involved and the project does not default.

IOWADOT has a low satisfaction with sureties, due to the lack of communication between IOWADOT and the surety. A performance bond has become a cost of doing business, which IOWADOT believes brings nearly no benefit. Currently, it is required by law to bond 100 percent of the project amount that is at risk. IOWADOT believes that there would be a benefit to increasing the minimum contract value that requires a 100 percent bond from $25,000 to a reasonable number. The current threshold for a 100 percent bond ($25,000) was established thirty years ago and is an arbitrary number.

IOWADOT would consider using an alternative means of screening/evaluating contractors in place of performance bonds. IOWADOT suggested replacing the performance bond system with performance-based contractor evaluations because a performance-based contractor system exists, works well at IOWADOT, and is accepted by the industry. IOWADOT would also consider using another means to screen/evaluate contractors as a supplement to the use of performance bonds, because doing so would save money.

Agency's views on the model for performance-based prequalification

IOWADOT believes that the model could help drive the successful delivery of projects if the model is powerful enough to impact large contractors to the same extent as small contractors. Because IOWADOT already includes performance evaluations in the prequalification of a contractor, it is not anticipated that implementation of the model would change project cost, project duration, risk of contractor defaults, or staff responsibilities. The project-specific prequalification aspect of the model could be used for special design bid build projects to further ensure that specific qualifications are available on those projects, such as specialty geotechnical jobs, or complex structural jobs. The model could be implemented at IOWADOT, but could experience a challenge with the industry if people believe it incorporates subjective evaluations. Finally, IOWADOT suggested that project-specific prequalification not be tied to alternative project delivery. Rather, IOWADOT suggested the use of a two-step prequalification system that only allows the bids of the contractors that pass the qualifications to be opened because then people believe this eliminates subjectivity. However, it is it is likely that there could still be industry opposition to the two-step system, even though the subjectivity is considered eliminated.

Table 45. IOWADOT project data.

| Year | Value of Awarded Contracts |

Number of Contracts |

Number of Defaults |

2007 |

$431,783,499.92 |

620 |

0 |

2008 |

$507,727,178.97 |

727 |

0 |

2009 |

$805,490,601.73 |

849 |

0 |

2010 |

$705,230,796.94 |

845 |

0 |

2011 |

$730,748,762.18 |

939 |

0 |

Agency Name: Oklahoma Department of Transportation (ODOT-OK)

Delivery method(s) the organization is allowed to use:

Does the agency use performance-based prequalification in any form? Yes

Which projects require performance bonding? All

What is the value of the performance bonds required for projects? 100 percent of construction cost

Agency’s prequalification process

ODOT-OK has a prequalification program based on a review of the contractor’s financials, experience, and equipment and places the heaviest weight on a contractor’s financial analysis. Contractors are required to renew the prequalification every two years. However, the prequalification renewal clock resets every time a contractor completes a project with ODOT-OK, in these cases a contractor is required to renew at least every five years. Contractors need to prequalify for specific classes of work and complete a favorable financial analysis. Post-project performance evaluations are conducted and can impact prequalification status. State statute allows three unsatisfactory evaluations in a 1-year period before suspension or debarment may be considered. The outcome of the financial analysis determines the total value of ODOT-OK work that the contractor may bid on within a specific class. This is a pass/fail test, where the contractor’s financials need to exceed the value of the projects under contract, plus the value of the contracts the contractor wants to bid on in a given letting.

The management and implementation of the prequalification program requires 67.5 percent of a full-time employee, which consists of one clerk at 40 percent, a second clerk at 25 percent, and a supervisor at 2.5 percent. The size, type, and/or complexity of a project does not change the effort required to prequalify.

The contractor performance evaluations are conducted at the completion of every project. The contractor receives a copy of the completed performance evaluation. ODOT-OK has no clear policy on whether or not the contractor has to be informed of a negative evaluation. ODOT-OK does not have a formal appeals process in place for a contractor that receives a negative performance evaluation, but it allows an informal appeal to be made to an individual one level higher than the person who completed the evaluation. A negative performance evaluation does not automatically disqualify a contractor from future work. There is no mechanism to permit a negative performance evaluation to impact the bidding capacity of a contractor, short of suspension or debarment. All performance evaluations remain on the record indefinitely. ODOT-OK believes that project performance evaluations enhance quality, timely completion, and contractor cooperation with the resident office.

The interviewee stated that the most effective practice of the existing prequalification program was the financial analysis and its use to determine bidding eligibility.

Agency’s experience with performance bonding and sureties

ODOT-OK requires all projects to have a performance bond valued at 100 percent of the construction cost. It has occasionally met with a surety when a contractor has had a performance issue. Beyond those meetings, ODOT-OK has no knowledge of what the surety may be doing behind the scenes to address the issue.

Overall, ODOT-OK is satisfied with sureties and the way they manage performance bonding. It believes that the current system is effective, as evidenced by the low default rate.

ODOT-OK would not consider using an alternative means to screen/evaluate contractors in place of performance bonds.

Agency's views on the model for performance-based prequalification

The ODOT-OK design bid build prequalification system is similar to the tier one and tier two elements of the proposed performance-based contractor prequalification model. The ODOT-OK design bid build prequalification system also includes something similar to tier three of the proposed model for specialty projects (like cable barrier projects). The interviewee felt that the ODOT-OK system could be improved by determining bonding/surety at the annual prequalification stage; currently, ODOT-OK only uses bonding/surety information at the project bidding stage to allow/disallow a contractor to bid on a specific project. By including the bonding/surety information in the annual prequalification stage, ODOT-OK only has to manage the bonding/surety evaluation once, rather than for every project each contractor bids on. The maximum bidding limit is set at 2.5 times the working capital (working capital = current assets - current liabilities).

Table 46. ODOT-OK project data.

Year |

Value of Awarded Contracts |

Number of Contracts |

Number of Defaults |

2007 |

$633,768,354.70 |

1,095 |

0 |

2008 |

$703,136,032.36 |

1,135 |

0 |

2009 |

$965,306,457.21 |

1,556 |

0 |

2010 |

$744,806,340.68 |

1,625 |

0 |

2011 |

$739,557,693.21 |

1,968 |

0 |

Agency Name: Utah Department of Transportation (UDOT)

Delivery method(s) the organization is allowed to use:

Design-Bid-Build

Construction Manager/General Contractor

Design-Build

Public-Private Partnership

Does the agency use performance-based prequalification in any form? Yes

Which projects require performance bonding? All projects

What is the value of the performance bonds required for projects? Projects under $500 million require a bond of 100 percent of the project value; projects over $500 million require a bond of 50 percent of the project value.

Agency’s prequalification process

UDOT requires contractors to prequalify on an annual basis for projects over $1.5 million. Prequalification is based on a contractor’s financial capacity, performance evaluation, and amount of experience working for UDOT. Currently, financial capacity carries the most weight in a contractor’s ability to prequalify. However, in about a year, UDOT will implement a new prequalification process that will increase the weight of performance evaluations and change the performance evaluation system. The current prequalification system requires the work of one full-time UDOT employee, regardless of the project size, type, or complexity.

Contractors become prequalified for a certain amount of work. If a contractor’s financial capacity is over $50 million, that contractor can bid on any UDOT work. Prequalification is not required for projects less than $1.5 million; therefore, UDOT’s prequalification system is really made for contractors with financial capacities between $1.5 million and $50 million, as the agency believes contractors in this range pose the greatest risk. The prequalification system does not vary based on the project type, size, or complexity.

Contractors are prequalified for a certain amount of work, which is determined by multiplying their adjusted equity by their performance factor and the sum of their experience rating factor, financial factor, and additional experience factor. A contractor’s adjusted equity is determined by the contractor’s financial statement. The performance factor is based on the average of the contractor’s last 3 years of performance evaluations completed by the resident engineer, with a minimum of three ratings. The experience rating factor is determined by the contracts, estimates, and agreements manager, based on a contractor’s amount of experience working on UDOT projects. The comptroller determines a contractor’s financial factor, based on information from the contractor’s financial statement. The contracts, estimates, and agreements manager determines the additional experience factor, based on the contractor’s average performance factor for the past year.

UDOT’s current contractor performance evaluation system is conducted by the resident engineer at the completion of every project, uses a ten-point scale for evaluation, and is very subjective. Interim performance evaluations are suggested as a partnering tool. The performance evaluation covers quality control and workmanship; safety; work zone traffic control; EEO/labor compliance; environmental compliance; administration, organization, and supervision; partnering; schedule; and public relations. In general, UDOT’s ratings have been very high; any low ratings didn’t have the data or hard evidence to back them up because the evaluations were so qualitative. If a contractor is given an overall performance rating of less than 70 percent, an explanation is required.

Contractors receive a copy of their performance ratings. UDOT is required to notify contractors before it submits a negative performance evaluation, and there is an appeals system in place. All performance evaluations remain on the record for three years. A negative performance evaluation does not automatically disqualify a contractor from future work, but it does limit the contractor’s bidding capacity.

UDOT is currently developing a new electronic performance evaluation system that will focus on objective measures of quality, safety, and schedule, and will be more heavily weighted when calculating the amount of work for which a contractor is prequalified. UDOT’s new performance evaluation system will include a three-strike approach. The department will give contractors two attempts to fix an identified performance issue, and after the third incident of the same performance issue, the contractor’s bidding privileges will be modified.

Agency’s experience with performance bonding and sureties

UDOT requires all projects under $500 million to have a performance bond of 100 percent of the project value. In the past, UDOT has investigated reducing the amount of the performance bond, but found that the economic benefits were minimal and not commensurate with the risk. For projects over $500 million, the performance bond value is reduced to 50 percent of the project value. Other than project value, nothing changes the performance bonding requirements. UDOT estimates that it takes one full-time employee to manage the performance bond requirements.

Performance bonds are not a part of UDOT’s prequalification process. For each project, only the awarded contractor is required to supply a performance bond; thus, not all of the bidding contractors have to go through the effort. Performance bonds are not included in the annual prequalification because UDOT has experienced fluctuations in contractor’s abilities to get performance bonds over the course of a year.

Other than one default that happened 5 years ago, UDOT has had very little experience, if any, working with sureties. That default case was the only time that UDOT remembers working with a surety on a project or even initiating contact with a surety about a performance issue. In the case of the default, UDOT notified the surety of the performance problem, the surety didn’t do anything to prevent the default, and the contractor defaulted. There was an 8 to 12 month delay on the project as a result of the default, which UDOT does not believe the surety could have decreased. As a result of the default, UDOT incurred additional project costs, due to added construction management. Further, the public was affected by the inconvenience of an idle construction project.

UDOT has never had a surety work proactively with a contractor to improve performance or attempt to avoid a default unless the surety was first called in by UDOT. In UDOT’s experience, sureties are not involved in any aspect of a project, unless UDOT calls them. UDOT does share poor contractor performance evaluations with the surety, but it has never received responses from the surety in those cases.

UDOT would not consider eliminating or supplementing the performance bond requirement on projects. The department regards performance bonding as a form of cheap insurance.

Agency’s views on the model for performance-based prequalification

Overall, UDOT believes that the model is headed in the right direction. The agency is very supportive of incorporating contractor performance into the prequalification process, but has identified two areas of the model that could use some reconsideration: performance bonding on an annual basis and the reduction of the value of the performance bond.

UDOT has experienced fluctuations in the performance bond values that contractors are able to secure over the course of a year. These fluctuations are a reflection of the condition of contractors’ business over the course of the year. Because such fluctuation cannot be captured in an annual performance bond requirement for prequalification, UDOT requires a performance bond for every awarded contract. While UDOT understands it would be more convenient for a contractor to acquire only one performance bond over the course of the year, the agency believes this is too risky to pursue, as indicated in tier one of the model.

UDOT previously considered reducing performance bond amounts on projects as a cost-savings measure. However, the agency found that the savings from the reduction of the performance bond value were negligible and not worth the additional risk. As a result, UDOT does not believe there is a benefit to including the reduction of the performance bond amount in tier two of the model.

Year |

Value of Awarded Contracts |

Number of Contracts |

Number of Defaults |

2007 |

$441,855,551.30 |

177 |

0 |

2008 |

$460,590,019.31 |

143 |

0 |

2009 |

$1,090,116,707.13 |

206 |

0 |

2010 |

$557,318,674.76 |

180 |

0 |

2011 |

$636,475,647.30 |

134 |

0 |

Agency name: Virginia DOT (VDOT)

Delivery method(s) the organization is allowed to use:

Design-Bid-Build

Design-Build

Public-Private Partnership

Does the agency use performance-based prequalification in any form? Yes

Which projects require performance bonding? All projects over $250,000

What is the value of the performance bond required for projects? 100 percent of the project’s value

Agency’s prequalification process

VDOT prequalifies contractors every three years and requires annual reviews and updates. VDOT has two full-time employees to manage the contractor prequalification process. This process does not include contractor performance evaluations, which are conducted by VDOT inspectors in the field on a regular basis. The prequalification status is based on a contractor’s overall safety score, VDOT’s performance evaluations, and a financial review. The financial review is not in-depth and is only intended to establish whether a contractor’s financial standing is positive or negative. The review only impacts the bonding requirements, not the prequalification of the contractor. VDOT has five prequalification status levels: prequalified, prequalified probationary, prequalified inactive, prequalified conditional, or prequalified subcontractor.

Prequalified status allows contractors to bid on all projects up to their bonding ability and requires a minimum prequalification score of 80, a minimum performance evaluation score of 85, and a minimum safety score of 70. A prequalified probationary or prequalified inactive status indicates that a contractor meets the minimum safety score and has demonstrated the ability to complete the type of work for which prequalification is requested, but has not performed work for VDOT, and thus does not have a performance evaluation score. A firm that is probationary or inactive can have no more than three ongoing projects with VDOT at one time, and each project needs to have a contracted value of less than $2 million. A firm is determined to be conditionally prequalified when its quality and/or safety scores are below VDOT’s desired standards. A conditionally prequalified firm can have only one active project at any given time and is limited to a maximum value of $1 million in contracted work at one time. A prequalified subcontractor goes through a similar process, but can only bid on subcontractor work.

A contractor’s prequalification status is determined by the prequalification score, of which VDOT’s performance rating represents 70 percent and the company’s overall safety score (based on the Experience Modification Ratio) represents 30 percent. VDOT’s contractor performance ratings are conducted on all projects on a monthly basis, and a comprehensive score is calculated at the end of the projects. The performance evaluation, which is automated through an electronic form, assesses all scopes of work, quality, and safety on a four-point scale (ranges from 1 to 4). A VDOT project inspector is required to fill out the contractor performance evaluations monthly. If a particular element of a project is inactive, the inspector assigns a score of 0 and does not include that score in the overall monthly performance score. At the end of the project, the interim (monthly) scores are converted into a comprehensive project score. The comprehensive scores remain on the record at VDOT permanently, and there is an appeals process available for contractors to dispute any performance ratings.

Within the performance ratings, every aspect, other than project management, is evaluated objectively and compared to requirements and specifications. Project management is more subjectively evaluated and is rated using an A, B, C, D, and F rating scale (like school grades). VDOT is satisfied with this process because it is mostly objective and there are notes in the project diaries or reports that correspond to the project. Contractors and subcontractors are removed from the list of prequalified bidders if they receive one score below 60, or if in a 24 month period, they receive 3 scores below 70 on a contractor performance evaluation annual or final report. Lower contractor performance evaluation scores can also impact a contractor’s prequalification status level.

Because the contractor performance evaluation is so heavily weighted in VDOT’s prequalification, contractors that are new to VDOT can have difficulty quickly becoming fully prequalified. VDOT has the abililty to provide a project waiver if a contractor has no experience with VDOT and therefore no contractor performance evaluation. The waiver considers VDOT’s past performance evaluations of the contractor’s key team members (if they have done work for VDOT in another capacity), performance ratings from other State transportation agencies, and/or accomodation letters from owners of projects the contractor completed that were similar to VDOT’s work.

Overall, VDOT believes that the current prequalification process provides for better projects, more bidders on projects, and overall improvement in final work products. The number of prequalified bidders has increased since the implementation of VDOT’s performance-based prequalification process. It is speculated that the higher number of bidders is a result of the five different prequalification status levels that replaced the previous pass/fail prequalification. The prequalification status levels also allow contractors to stumble and not be completely disqualified from all VDOT work.

Agency's experience with performance bonding and sureties

Overall, VDOT has had good experiences with sureties and performance bonding. The agency averages two possible defaults a year, and one a year, at most, actually defaults. VDOT informs sureties about performance issues 100 percent of the time and has never had a surety inform VDOT about a performance issue on a project. VDOT has never had a dispute with a surety about a default, and every time VDOT has been through a default, the surety finished the project; the surety didn’t monetarily reimburse the agency. When a default occurs, the project experiences, on average, a 3-month shutdown.

VDOT estimates that it takes the equivalent of one full-time employee working ten days per month to manage the performance-bond system; however, this work is spread among many department staff. VDOT believes it is possible for a surety to work with a contractor to avoid default, once the surety has been informed of a performance issue, but it has no firsthand knowledge of this type of action.

VDOT has used a construction manager in place of a surety when a contractor has demonstrated the ability to perform the work and makes the lowest bid, but cannot secure a bond for the project. In this case, the construction manager monitors the entire project and receives all VDOT project payments. Construction managers are responsible for paying themselves and all subcontractors, and whatever is left goes to the contractor. VDOT does not know the exact cost of this alternative because the construction manager is hired directly by the contractor.

VDOT is willing to use this system again. While the agency does not currently evaluate a construction manager’s ability to perform work, if the system did replace performance bonding, some sort of qualification system would be needed for construction managers because they are not at risk on the project. The system would provide larger companies with the opportunity to be the construction manager and mentor the contractor.

VDOT is passionate about the inclusion of contractor performance-based evaluations in prequalification regulations and requirements. Overall, VDOT views the model as a great framework for performance-based prequalification for agencies that currently prequalify based on only financial requirements. However, VDOT would not implement the model verbatim because it is not an improvement over the system the agency has in place.

VDOT thinks the financial capacity determination and reduction of performance bonds are redundant because sureties already complete these activities. Because sureties are at risk on a project, they conduct a very thorough examination of a firm before they provide a performance bond, which includes an analysis of the firm’s financial capacity. VDOT does not have the expertise or resources to determine a contractor’s financial capacity to the same depth and accuracy as a surety can. The second redundancy is the reduction of the performance bond value for firms that exceed minimum performance expectations. VDOT believes this essentially already occurs when sureties offer lower-cost performance bonds to firms they consider stable or lower risk than unstable or higher-risk firms.

Year |

Value of Awarded Contracts |

Number of Contracts |

Number of Defaults |

2007 |

$551,527,205.05 |

389 |

0 |

2008 |

$622,724,764.51 |

409 |

0 |

2009 |

$416,585,354.88 |

283 |

0 |

2010 |

$547,838,809.66 |

401 |

0 |

2011 |

$499,837,802.09 |

329 |

0 |

Agency name: Washington State DOT (WSDOT)

Delivery methods the organization is allowed to use:

Design-Bid-Build

Design-Build

Does the agency use performance-based prequalification in any form? Yes

Which projects require performance bonding? All projects

What is the value of the performance bonds required for projects? For projects under $500 million, WSDOT requires a performance bond of 100 percent of the project’s construction value. For projects over $500 million, the value of the performance bond can be reduced on a project-by-project basis.

Agency’s prequalification process

WSDOT prequalifies contractors annually (typically in March). The prequalification process is dictated by sections 468-16-010 through 468-16-210 of the Washington Administrative Code. WSDOT estimates that it takes the equivalent of two full-time employees to manage the prequalification process. However, this work is not the sole responsibility of two full-time employees; it is spread among many people. The workload fluctuates throughout the year; in March, the workload is heavy, due to the annual prequalification process, and at other times of the year, when the project load is light, the prequalification workload is light, too.

The three most important prequalification factors are financial capacity, past work experience, and a prime contractor’s performance report. The financial capacity of a contractor, which is evaluated using the contractor’s financial statement, determines the size of a project that the contractor can bid on. WSDOT requires prime contractors to self-perform 30 percent of the work on the project they are bidding on. Past work experience is evaluated to determine what type of work a contractor is qualified to perform, which involves speaking with past clients about the contractor’s work. The prime contractor performance report is completed by the WSDOT project team at the completion of all WSDOT projects. The report is then shared with the contractor, prior to its submittal to WSDOT upper management. There is an appeals process, and the results can increase or decrease the final bidding capacity rating the contractor receives from WSDOT.

WSDOT is happy with its current prequalification process and feels it gets better projects as a result of the process. The prime contractor’s performance report and past work experience are the most useful parts of the evaluation because they ensure that a contractor has the ability and experience to successfully complete a project (which essentially prevents a paving contractor from bidding on a bridge project and vice versa). The financial capacity is similar to the bonding process and does not add as much.

Agency’s experience with performance bonding and sureties

For all projects under $500 million, WSDOT is legally required to have a performance bond for 100 percent of the project value. A performance bond is required for projects over $500 million, but the value of the bond may be reduced on a case-by-case basis (though this reduction has only happened a couple times on mega projects, due to the difficulty of bonding them). WSDOT’s performance-bond process requires the completion of a standard form, and it is estimated that the workload for this procedure equates to a partial full-time employee. When there is an exception to the process or a performance issue is identified, the workload can increase to one full-time employee. If a surety has to become involved in the project, the project team’s workload increases to manage the surety and bring the surety up to speed on the project.

WSDOT has not had a recent project default. In all recent cases, the surety stepped in before default and finished the project, which resulted in no stoppage or lost time on the project. When a performance issue surfaces on a project, WSDOT contacts the surety for assistance 100 percent of the time. Usually, the surety has not learned of the performance issue prior to WSDOT’s contact. WSDOT typically has to contact a surety on 5 to 10 percent of all projects. In the recent economic climate, this amount of contact has increased minimally. Though WSDOT has not had any recent defaults, WSDOT has also not had a surety work with a contractor early in the project to avoid default.

A contractor’s performance is not included in the performance-bond process (outside of the standard evaluations used by the surety). Any performance-based evaluations of the contractor are included in the administrative prequalification process. WSDOT’s performance ratings (which are conducted at the completion of a project) have never been shared with a surety.

Overall, WSDOT thinks performance bonds are valuable and considers sureties essential to projects. Sureties have proved useful because they have assisted with the completion of projects before they reached default, and if nothing else, threatening to call a surety is an effective way to improve a contractor’s performance.

Agency’s views on the model for performance-based prequalification

The performance-based prequalification model is similar to WSDOT’s current process. One difference is that WSDOT cannot legally lower the performance bond requirement for a contractor, while the second tier of the model adjusts the performance bond requirement if the contractor exceeds the minimum performance standards. Because WSDOT has already implemented a system that is similar to the model, the agency does not believe the new model would result in any changes to project cost, duration, staff responsibilities, or risk of contractor default. WSDOT does believe that it has gotten better projects because it uses a performance-based system to prequalify contractors, since the agency has been able to procure contractors with the right experience. However, WSDOT does not have any quantifiable proof that it has gotten better projects because of its use of this system.

Year |

Value of Awarded Contracts |

Number of Contracts |

Number of Defaults |

2007 |

$406,244,656.83 |

135 |

0 |

2008 |

$319,250,602.30 |

117 |

0 |

2009 |

$281,766,937.37 |

146 |

1 |

2010 |

$74,202,021.55 |

64 |

0 |

2011 |

$6,253,163.82 |

13 |

0 |