U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

Federal Highway Administration Research and Technology

Coordinating, Developing, and Delivering Highway Transportation Innovations

| REPORT |

| This report is an archived publication and may contain dated technical, contact, and link information |

|

| Publication Number: FHWA-HRT-14-034 Date: August 2014 |

Publication Number: FHWA-HRT-14-034 Date: August 2014 |

Agencies currently use numerous approaches to incorporate contractor performance into the prequalification process. While the variation is substantial, the motivation to implement these systems is generally the same-to correlate contractor performance with a contractor’s ability to competitively bid, which therefore creates an incentive for good performance and encourages marginal performers to improve. The following expresses the philosophy of including performance in the contracting process:(29)

The concept of performance-based contracts originated from a consideration of four factors, namely, (a) the increasing lack of personnel within the national road departments...(b) the frequency of claims...(c) the need to focus more on customers’ satisfaction by seeking to identify the outcomes, products, or services that the road users expect to be delivered, and by monitoring and paying for those services on the basis of customer-based performance indicators; and (d) the need to shift greater responsibility to contractors throughout the entire contract period as well as to stimulate and profit from their innovative capabilities. [Emphasis added]

Four representative agencies with different successfully implemented systems-FDOT, IOWADOT, ODOT-OH, and MTO-can serve as a foundation for a generic model of the performance-based contractor prequalification process.

FDOT has had a contractor performance rating system in place since 1982, which it uses during its prequalification process.(39) FDOT evaluates contractor performance in the following 10 areas:

Quality.

Management.

Cost.

Traffic.

DBE/EEO participation.

Environmental.

Traveling public.

Agency cooperation.

Property owner cooperation.

Submittals.

Florida uses performance rating procedures and guidelines to rate contractors and has an appeal process in place for the contractor’s performance rating.

The core of FDOT’s approach is the determination and use of an AF. If a contractor already works for FDOT and has at least three “contractor past performance reports,” FDOT uses the components shown in table 66 to first determine each contractor’s Ability Score (AS). FDOT sums the scores of the contractor past performance reports together with the previous average score and then divides by the total number of scores used. (A separate evaluation process is used to determine an AS for new contractors.) FDOT then uses the matrix shown in table 67 to assign AFs. If the contractor has two or more contractor past performance reports in which it received an AS lower than 76 in the 12 months preceding the contractor’s fiscal year end date, then their assigned AF is reduced to 4.

Table 66. FDOT ability score.(39)

AS |

|

Maximum Value |

|

Organization and Management |

|

Experience of principals |

15 |

Experience of construction supervisors |

15 |

Work Experience |

|

Completed Contracts |

|

Highway and bridge related |

25* |

Non-highway and bridge related |

10 |

Ongoing Contracts |

|

Highway and bridge related |

25* |

Non-highway and bridge related |

10 |

Total |

100 |

| * Maximum value shall be increased to 35 if applicant’s experience is exclusively in highway and bridge construction. |

AF |

|

If AS is: |

AF is: |

98-100 |

15 |

94-97 |

14 |

90-93 |

12 |

85-89 |

10 |

80-84 |

8 |

77-79 |

5 |

74-76 |

4 |

70-73 |

3 |

65-69 |

2 |

64 or less |

1 |

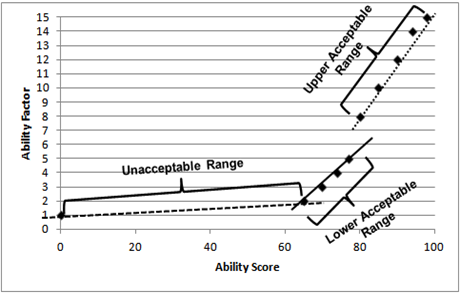

Table 66 shows the impact of past performance on a contractor’s ability to bid. Contractors with an AS of 80 or above can receive an AF upwards of 8 times those of contractors with an AS of less than 80. When the AS drops below 65, a contractor receives no benefit from the score and the ultimate ability to bid is based strictly on financial capacity. The FDOT system shows the powerful impact that the inclusion of past performance in bidding capacity calculation can have. In theory, a contractor with a perfect performance record-reflected by an AS of 100-can bid on 15 times more work than it could have bid on if the decision was based solely on the surety industry’s performance bonding capacity (as illustrated in the formula to determine the FDOT Maximum Capacity Rating (MCR) in figure 29).

Figure 28. Line graph. FDOT contractor ability score/ability factor relationship.

Once an AF has been determined, FDOT uses it to determine the MCR, or “the total aggregate dollar amount of uncompleted work an applicant may have under contract at any one time as prime contractor and/or subcontractor.”(39) The formula for MCR follows:

![]()

Figure 29. Equation. Maximum capacity rating.

Where:

MCR = Maximum Capacity Rating

AF = Ability Factor

CRF = Current Ration Factor (or Adjusted New Assets/Adjusted Net Liabilities.

ANW = Adjusted Net Worth

FDOT further provides that contractors with an AF greater than 80 and a current ratio factor greater than 1 can request an increase in their MCR if they can provide a letter from a surety that shows that their current bonding capacity exceeds the calculated MCR. There are two tiers within this group that are eligible for a new limit to their MCR, termed their surety capacity (SC). For contractors with an AF of 91 and greater, the MCR will be the aggregate of contracts amount specified in the surety commitment letter. For contractors with an AF between 80 and 90, the following formula is used in conjunction with table 68.

![]()

Figure 30. Equation. Surety capacity.

Where:

SC = Surety Capacity

SM = Surety Multiplier

MCR = Maximum Capacity

CRV = Construction Revenues

TRV = Total Revenues (as set forth in applicant’s financial statements)

Table 68. FDOT ability score/surety multiplier.

AS |

Surety Multiplier |

88 |

6.8 |

87 |

6.2 |

86 |

5.6 |

85 |

5.0 |

84 |

4.6 |

83 |

4.2 |

82 |

3.8 |

81 |

3.4 |

80 |

3.0 |

FDOT’s approach shows a clear impact of a contractor’s past performance on a contractor’s access to future work, also seen through the MCR value’s linear relationship with past performance. For contractors with superior ratings (i.e., those with ratings greater than 80), there is also the potential for “bonus” access to available work, in the form of additional capacity adjustments. This approach encourages contractors to perform well without indirectly granting a subsidy to poorly performing contractors.

While the system does not provide a direct financial benefit to the owner by reducing total bonding costs, it clearly creates an incentive that can motivate contractors to improve their performance. Like many other jurisdictions, Florida includes a rather lengthy list of causes for suspension, revocation, and denial of qualification in their prequalification process. This list provides FDOT with an additional tool to use to address extreme cases of substandard contractor performance.

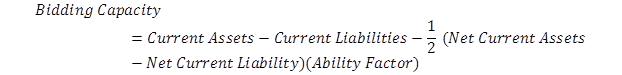

Figure 31 is the formula used by IOWADOT to determine the amount of work a contractor can bid on, based on its past performance. That performance is quantified with the ability factor, which is derived from contractor performance evaluations.

Figure 31. Equation. IOWADOT bidding capacity calculation.

ODOT-OH evaluates a contractor or subcontractor’s performance during each of their projects and then uses the evaluation to determine the amount of work the contractor can bid on. The system is quite simple and is included here, in part, to illustrate a performance-based contractor prequalification process in its most basic form. ODOT-OH’s process includes the use of rating guidelines and it mandates that additional supporting documentation requirements are met in instances of poor contractor performance. Contractor performance evaluations from the previous calendar year are averaged and then used to determine a prequalification factor, as shown in table 69.

Table 69. ODOT-OH prequalification factor matrix.

Previous Year’s Average Evaluation Score (Percent) |

Prequalification Factor |

85 or greater |

10 |

80-84 |

9 |

70-79 |

8 |

60-69 |

7 |

55-59 |

6 |

50-54 |

5 |

Below 50 |

1 |

The contractor’s bidding capacity is then determined by multiplying its net asset value-as presented in the documents submitted for ODOT-OH’s administrative prequalification process-by the prequalification factor. As a result, contractors with good performance are rewarded with increased bidding capacity, while poorly performing contractors have decreased access to work. ODOT-OH has also created a Prequalification Review Board to hear appeals of contractor performance evaluation results and other qualification-related decisions. The board demonstrates ODOT-OH’s recognition of the importance of establishing processes that are perceived as fair and it also helps ensure contractor confidence in the system.

MTO has maintained its performance-based prequalification process since the 1960s and relies on this process in place of bid bonds and performance bonds. MTO uses a comprehensive contractor performance rating system and evaluates contractor performance across a wide range of categories, using objective criteria wherever possible. MTO annually establishes contractor performance ratings using CPRs calculated for the previous three years. The CPR is calculated as a weighted average, in such a way that recent ratings are weighted higher. As a result, the most recent poor and improved performances have a greater impact on the CPR. MTO also provides rating guidelines and a process for contactors who would like to appeal the contractor performance ratings.

MTO’s system includes two components that address contractor performance: the infraction report process and the CPR system. The infraction report process is designed to address very significant contract incidents across four areas: project management, quality, safety, and environmental. The infraction report system is activated when a contractor commits a serious breach of contract that includes, but is not limited to, the following specific behaviors:(34)

Failure to abide by tendering requirements.

Tender declarations that are incomplete or inaccurate.

Failure to abide by general conditions of contract.

Serious issues that affect safety or the environment.

The [unsatisfactory] timeliness of the completion of the work and services.

The issuance of any Notice of Default.

The manner of the [unsatisfactory] resolution of any disputes, and whether such disputes were resolved in accordance with the prescribed provisions of the contract.

When such an incident occurs, a report is prepared and submitted to the MTO Qualification Committee (comprised of senior ministry staff) for review. The committee then decides how to proceed and implements one of the following:

Takes no further action.

Issues a warning letter.

Applies sanctions.

Sanctions that arise from infraction reports are applied to a contractor’s contractor financial rating, and as a result, access to work is immediately reduced.

MTO uses a unique method to determine the impact of the CPR system. Contractors that maintain a performance rating of more than 70 are placed in a “green zone” and can bid on work that falls within the contractors’ financial rating, based on the evaluation of financial documents that the contractor submits during the administrative prequalification process. If a contractor’s performance rating falls below 70, MTO imposes a dollar-value limit on the work it can take on, called the Maximum Workload Rating (MWR), to restrict the contractor’s ability to bid. The MWR is the highest annual total dollar value of work awarded to a contractor over the previous five fiscal years.

When contractors’ performance ratings are greater than 55 and less than 70, they are placed in a “yellow zone.” The qualification committee can decide merely to impose the MWR limitation or to reduce it by up to 20 percent for contractors placed in this zone. Contractors are put in a “red zone” if their performance ratings are between 35 and 55. If placed in the red zone, the contractor’s MWR is automatically reduced, based on the rating the contractor receives on a linear scale that ranges from 20 to 100 percent of total MWR. Any sanctions imposed during the infraction process can further reduce the contractor’s MWR.

As mentioned earlier, the Ontario process is also unique in that MTO does not require bonding, which results in a direct financial benefit to the ministry. A contractor’s performance does not impact the contractor’s costs of work; it impacts a contractor’s access to work. Of course, contractors pay the cost of good performance, which corresponds with an increased value to the owners, who benefit from the higher level of performance.(17) While the punitive nature of reducing a contractor’s access to work creates a significant incentive to improve quality and/or contract performance, it does not necessarily compensate the contractor for the additional cost that higher performance may entail.

Ontario’s system impacts the contractors’ eligibility in various ways. Below are three scenarios that illustrate how the Ontario system applies in several scenarios.

Scenario A

A contractor is evaluated using the information shown in table 70.

Table 70. MTO scenario A evaluation.

Measure |

Value |

Basic Financial Rating |

$12 million |

Work on Hand |

$5 million |

Contractor Performance Index (CPI) |

78 |

MWR |

$5.5 million |

Infractions |

10 percent (Subcontractor drove excavator through creek) |

Available Rating |

($12 million - 10% ($12 million)) - $5 million = |

The contractor would like to submit a bid for a contract that requires a rating of $6 million and a MWR of $4 million.

Since the contractor has a CPI greater than 70, it falls in the green zone, and therefore is not subject to the MWR. However, the contractor only has $5.8 million of Available Rating (AR) and the contract requires an AR of $6 million. As a result, the contractor cannot submit a bid for this contract. Had the contractor not incurred the infraction, it would have been eligible to bid on this contract.

Scenario B

A contractor is evaluated using the information shown in table 71.

Table 71. MTO scenario B evaluation.

Measure |

Value |

Basic Financial Rating |

$25 million |

Work on Hand |

$11 million |

Contractor Performance Index (CPI) |

65 (Qualification Committee imposed MWR, with no additional reduction) |

MWR |

$8.8 million |

Infractions |

None |

Available Rating |

$25 million - $11 million = $14 million |

The contractor would like to submit a bid for a contract that requires a rating of $13 million and a MWR of $10 million.

Since the contractor has a CPI of 65, it is in the yellow zone. The Qualification Committee decided to impose a MWR on this contractor, with no further reductions applied. The contractor has $14 million of AR for a contract that requires a rating of $13 million and therefore meets the financial requirements. However, the contract also requires $10 million as its MWR. Since the contractor is subject to a MWR of $8,8 million, the contractor is not able to qualify to submit a bid for this project.

Scenario C

A contractor is evaluated using the information shown in table 72.

Table 72. MTO scenario C evaluation.

Measure |

Value |

Basic Financial Rating |

$425 million |

Work on Hand |

$51 million |

Contractor Performance Index (CPI) |

51 |

MWR |

$62.5 million |

Infractions |

15 percent (due to series of serious incidents of inappropriate traffic control) |

MWR Adjusted |

20 percent + (4 / 20 x 80 percent) = 36 percent $62.5 million - 15 percent - 36 percent = $30.625 million |

Available Rating |

($425 million - 15 percent ($425 million)) - $51 million = $310.25 million |

The contractor would like to submit a bid for a contract that requires a rating of $90 million and a MWR of $50 million.

Since the contractor has a CPI of less than 55, it is in the red zone. The Qualification Committee automatically imposed a MWR reduction of 15 percent for the infraction, as well as an additional MWR adjustment, based on the specific CPI assigned to the contractor. This large contractor has an AR of $310.25 million for a contract that requires an AR of $90 million. However, this contractor’s poor contract performance has resulted in a significantly reduced MWR. For contractors subject to a MWR, the contract requires a MWR rating of $50 million. This contractor only has a MWR of $30.625 million and therefore cannot qualify to submit a bid on this project.

The Ontario system is designed to treat large and small contractors equally when their performance falls below the expected standard. Nonetheless, a reduced financial capacity may have a significant impact on small contractors, whereas the work volume of large contractors with significant financial resources may not be greatly impacted, since they typically work for a wide range of transportation agencies in many geographical areas. When substandard performance forces MTO to impose the MWR limitation, the contractor-regardless of its size-cannot increase its MTO work volume above the highest amount of work that was successfully obtained in the past five years. This subsequently forces the offending firm to either seek work from agencies it has not previously worked with or to increase its workload for agencies for which it has, or is currently, performing work. This evaluation system increases a contractor’s uncertainty of its ability to bid when it receives poor evaluations, which creates a significant incentive for contractors to maintain satisfactory performance.