- Highway Finance

- Overall Highway Finance Trends

- Current Revenue Sources

- Historical Revenue Trends

- Overall Highway Expenditures

- Highway Capital Outlay Expenditures

- Innovative Finance

- Public-Private Partnerships

- Credit Assistance

- Debt Financing

- Innovations in Tolling

- Overall Highway Finance Trends

- Transit Finance

- Transit Funding

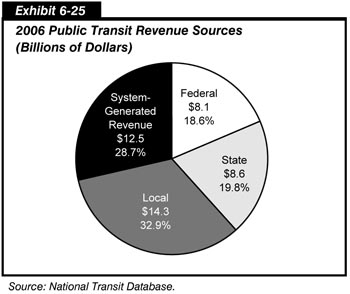

- Level and Composition of Transit Funding

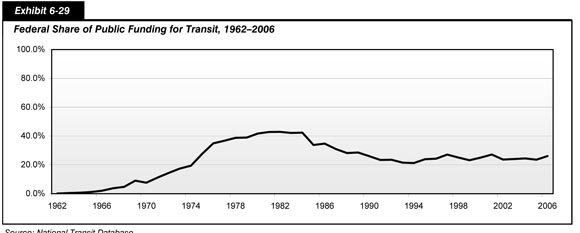

- Federal Funding

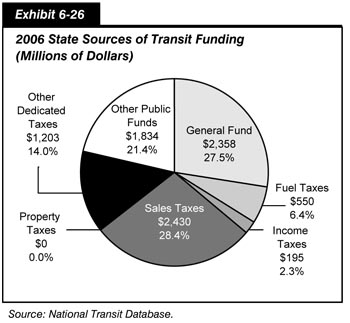

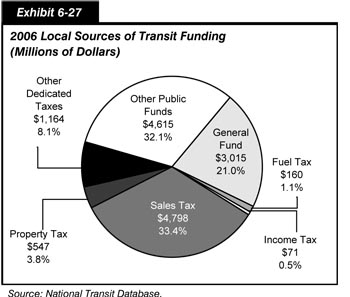

- State and Local Funding

- Level and Composition of System-Generated Funds

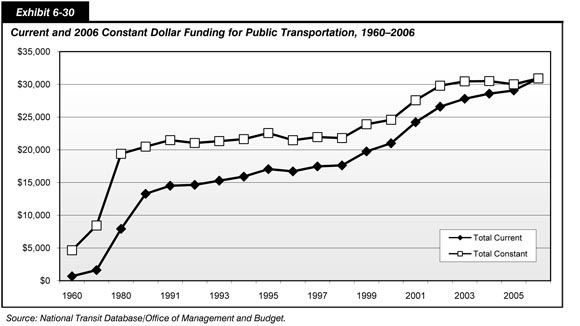

- Trends in Public Funding

- Funding in Current and Constant Dollars

- Capital Funding and Expenditures

- Operating Expenditures

- Operating Expenditures by Transit Mode

- Operating Expenditures by Type of Cost

- Operating Expenditures per Vehicle Revenue Mile

- Operating Expenditures per Passenger Mile

- Farebox Recovery Ratios

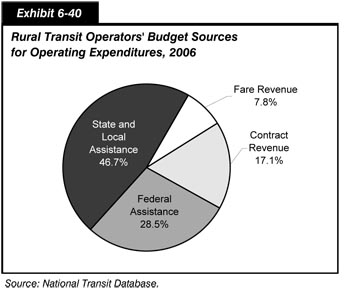

- Rural Transit

- Comparison

Highway Finance

This section presents a detailed look at highway finance from two different perspectives. First, this chapter examines overall highway finance trends, beginning with the revenue sources that support public investment in highways and bridges across all levels of government. This is followed by a detailed analysis of capital expenditures. Second, it examines tools that are allowing transportation agencies to finance surface transportation projects when traditional finance methods may not fully cover the need. These tools include the use of Public-Private Partnerships, credit assistance, debt financing, and innovations in tolling.

A separate section within this chapter explores the financing of transit systems. This is followed by a section comparing key statistics from the highway and transit sections with the information presented in the previous edition of this report. The goal of this chapter is to comprehensively address not only highway finance as supported by traditional means, but also the trends that may impact this area in the future.

Overall Highway Finance Trends

Innovative finance plays an increasingly important role in the delivery of highway infrastructure, but the vast majority of finance is still done by more traditional means. The following section takes a comprehensive look at all transportation funding in the United States; it presents information on the revenue sources that support public investment in highways and bridges, as well as the various types of investments that are being made by all levels of government. This is followed by a discussion of the current and historic roles of Federal, State, and local governments in highway funding. The section then concludes with a more detailed analysis of capital expenditures.

Private sector investment in highways would generally show up in the "other receipts" category in the exhibits in this section, to the extent that such investment is captured in State and local accounting systems.

Current Revenue Sources

As shown in Exhibit 6-1, $166.0 billion was generated by all levels of government in 2006 for the purpose of highway investment. Actual cash expenditures in 2006 for highways and bridges, however, were lower, totaling $161.1 billion. The $1.6 billion shown as drawn from reserves in the Federal column indicates that the cash balance of the Highway Account of the Federal Highway Trust Fund (HTF) declined by that amount during 2006. State and local governments, however, placed $6.6 billion in reserves, which means that $5.0 billion in revenue generated for highways at all levels of government was instead saved for spending at a later point.

| (Billions of Dollars) | Percent | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Federal | State | Local | Total | ||

| User Charges | |||||

| Motor-Fuel Taxes | $26.8 | $31.9 | $1.4 | $60.1 | 36.2% |

| Motor-Vehicle Taxes and Fees | $5.2 | $19.1 | $0.8 | $25.2 | 15.2% |

| Tolls | $0.0 | $6.7 | $1.4 | $8.1 | 4.9% |

| Subtotal | $32.1 | $57.7 | $3.6 | $93.4 | 56.3% |

| Other | |||||

| Property Taxes and Assessments | $0.0 | $0.0 | $8.6 | $8.6 | 5.2% |

| General Fund Appropriations | $2.4 | $4.9 | $19.6 | $26.8 | 16.1% |

| Other Taxes and Fees | $0.3 | $5.0 | $4.6 | $9.9 | 5.9% |

| Investment Income and Other Receipts | $0.0 | $4.2 | $5.3 | $9.5 | 5.7% |

| Bond Issue Proceeds | $0.0 | $11.9 | $5.9 | $17.8 | 10.7% |

| Subtotal | $2.7 | $26.0 | $44.0 | $72.6 | 43.7% |

| Total Revenues | $34.8 | $83.7 | $47.6 | $166.0 | 100.0% |

| Funds Drawn From (or Placed in) Reserves | $1.6 | ($2.8) | ($3.8) | ($5.0) | -3.0% |

| Total Expenditures Funded During 2006 | $36.3 | $80.9 | $43.8 | $161.1 | 97.0% |

Highway-user charges—including motor-fuel taxes, motor—vehicle taxes and fees, and tolls-were the source of 56.3 percent of the $166.0 billion of total revenues for highways and bridges in 2006. The remaining 43.7 percent of revenues came from a number of sources, including local property taxes and assessments, other dedicated taxes, general funds, bond issues, investment income, and other miscellaneous sources. Development fees and special district assessments are included under "Investment Income and Other Receipts" in Exhibit 6-1.

The degree to which highway programs are funded by highway-user charges differs widely among the different levels of government. At the Federal level, 92.3 percent of highway revenues came from motor-fuel and motor vehicle taxes in 2006. The remainder came from general fund appropriations; motor carrier fines and penalties; and some timber sales, leasing of Federal lands, and oil and mineral royalties.

Highway-user charges also provided the largest share, 69.0 percent, of highway revenues at the State level in 2006. Bond issue proceeds were another significant source of funding, providing 14.3 percent of highway funds at the State level. The remaining 16.7 percent of State highway funding came from general fund appropriations, other State taxes and fees, investment income, and other miscellaneous revenue sources.

Many States do not permit local governments to impose motor-fuel and motor-vehicle taxes, or they cap them at relatively low levels. Therefore, at the local government level, only 7.6 percent of highway funding was provided by highway-user charges in 2006. Local general funds, property taxes, and other taxes and fees were the sources of 68.9 percent of local highway funding. Bond issue proceeds provided 12.4 percent of local highway funding, while investment income and miscellaneous receipts provided the remaining 11.1 percent.

Historical Revenue Trends

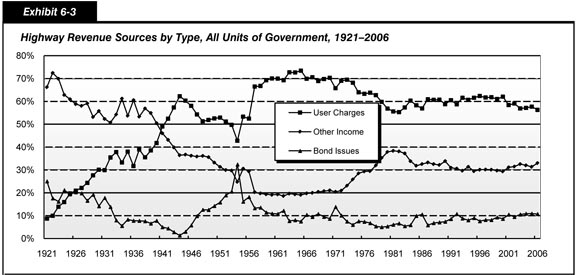

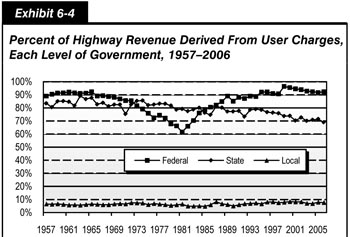

Exhibits 6-3 and 6-4 show how highway revenue sources have varied over time. Exhibit 6-3 identifies the different sources of highway revenue since 1921 for all levels of government combined. Exhibit 6-4 identifies the percentage of highway revenue derived from user charges by each level of government since 1957. Some of the variation in revenue sources shown in the graph portion of Exhibit 6-3 is caused by changes in the share of funding provided by each level of government over time; this topic will be discussed later in this chapter. In the early 1920s, when local government bore much of the responsibility for highway funding, property taxes were the primary source of revenues for highways. Property taxes have, however, become a much less significant source of revenue over time. In 2000, property taxes dropped to an all-time low of 4.7 percent of total highway revenue and remained at roughly that level through 2002; in 2003, property taxes began to climb slightly, reaching 5.2 percent of total highway revenues in 2006. The share of total highway revenues generated by bond proceeds has fluctuated over time, reaching a high of 32.4 percent in 1954. Since that time, combined highway and bridge programs have become less dependent on debt financing; this share has not exceeded 11 percent of revenues since 1971.

| Year | Fuel and Vehicle Taxes | Tolls | Property Taxes | General Fund Approps. | Other Taxes and Fees | Investment Income and Other | Issue Proceeds | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1921 | $0.1 | $0.0 | $0.7 | $0.1 | $0.0 | $0.1 | $0.4 | $1.4 |

| 1925 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 2.0 |

| 1929 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 2.7 |

| 1933 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 1.9 |

| 1937 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 2.7 |

| 1941 | 1.2 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 2.6 |

| 1945 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 1.9 |

| 1949 | 2.1 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 4.3 |

| 1953 | 3.1 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 1.3 | 6.5 |

| 1957 | 5.6 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 1.2 | 9.0 |

| 1961 | 7.7 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 1.3 | 11.8 |

| 1965 | 9.8 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 1.1 | 14.3 |

| 1969 | 13.0 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 1.9 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 1.9 | 19.9 |

| 1973 | 17.0 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 3.0 | 0.4 | 1.1 | 2.0 | 26.2 |

| 1977 | 19.6 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 5.4 | 0.8 | 1.8 | 2.2 | 33.0 |

| 1981 | 21.8 | 1.8 | 2.5 | 8.8 | 1.4 | 3.7 | 2.6 | 42.5 |

| 1985 | 33.6 | 2.2 | 3.5 | 9.9 | 1.9 | 4.3 | 6.1 | 61.4 |

| 1989 | 41.4 | 2.9 | 4.3 | 10.8 | 2.9 | 5.5 | 5.2 | 72.8 |

| 1993 | 50.8 | 3.6 | 4.7 | 10.6 | 4.0 | 6.8 | 7.8 | 88.4 |

| 1997 | 61.6 | 4.7 | 5.3 | 15.1 | 5.0 | 7.0 | 8.8 | 107.4 |

| 1998 | 64.3 | 4.7 | 5.8 | 14.5 | 5.1 | 8.2 | 9.0 | 111.6 |

| 1999 | 69.1 | 5.1 | 5.8 | 17.2 | 6.4 | 6.8 | 11.3 | 121.7 |

| 2000 | 75.6 | 5.7 | 6.1 | 19.3 | 5.7 | 7.3 | 11.3 | 131.1 |

| 2001 | 71.8 | 5.9 | 6.3 | 19.1 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 14.0 | 133.1 |

| 2002 | 73.1 | 6.6 | 6.5 | 20.3 | 7.5 | 8.1 | 12.7 | 134.8 |

| 2003 | 73.3 | 5.9 | 7.2 | 21.8 | 8.8 | 7.5 | 14.7 | 139.2 |

| 2004 | 76.4 | 6.6 | 7.5 | 23.6 | 7.9 | 7.6 | 15.8 | 145.3 |

| 2005 | 83.4 | 7.7 | 8.2 | 24.3 | 9.1 | 8.0 | 17.2 | 157.8 |

| 2006 | 85.3 | 8.1 | 8.6 | 26.8 | 9.9 | 9.5 | 17.8 | 166.0 |

| Year | Federal | State | Local | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1957 | 89.0% | 83.5% | 6.5% | 66.5% |

| 1961 | 92.1% | 84.7% | 5.7% | 69.9% |

| 1965 | 92.4% | 87.7% | 6.5% | 73.5% |

| 1969 | 88.1% | 82.5% | 6.5% | 69.8% |

| 1973 | 81.6% | 85.3% | 7.3% | 69.5% |

| 1977 | 74.3% | 83.2% | 6.4% | 63.8% |

| 1981 | 61.5% | 79.1% | 6.4% | 55.6% |

| 1985 | 78.8% | 76.2% | 4.7% | 58.3% |

| 1989 | 89.0% | 77.2% | 6.1% | 60.7% |

| 1993 | 89.0% | 78.5% | 6.9% | 61.6% |

| 1997 | 91.0% | 76.3% | 8.1% | 61.7% |

| 1998 | 90.7% | 75.9% | 7.5% | 61.8% |

| 1999 | 96.4% | 73.6% | 7.9% | 61.0% |

| 2000 | 95.5% | 73.9% | 8.3% | 62.0% |

| 2001 | 94.6% | 70.3% | 8.1% | 58.4% |

| 2002 | 93.9% | 72.6% | 8.2% | 59.1% |

| 2003 | 92.8% | 70.0% | 7.0% | 56.9% |

| 2004 | 92.4% | 70.8% | 6.9% | 57.1% |

| 2005 | 91.7% | 71.4% | 7.9% | 57.7% |

| 2006 | 92.3% | 69.0% | 7.6% | 56.3% |

Highway Statistics, various years, Tables HF-10A and HF-10.

Since the passage of the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 and the establishment of the Federal HTF, motor-fuel and motor-vehicle tax receipts have consistently provided a majority of the combined revenues raised for highway and bridge programs by all levels of government.

After peaking at an all-time high of 73.5 percent of highway revenues in 1965, the share represented by highway-user charges dropped to 55.2 percent in 1982. As shown in Exhibit 6-4, until 2000, the percentage had rebounded and stabilized in a range of about 60 to 62 percent. Since 2001, it has been slightly lower, ranging from 56 to 59 percent.

A corresponding pattern can be observed in the percentage of Federal highway revenue derived from highway-user charges as shown by the Federal line in Exhibit 6-4. During the early years of the HTF, over 90 percent of highway revenues at the Federal level came from fuel and vehicle taxes. From the late 1960s to early 1980s, this percentage declined, to a low of 61.5 percent in 1981. During this period, Federal motor-fuel taxes did not increase, and a growing percentage of Federal highway funding came from other sources. Since 1981, Federal motor-fuel taxes have increased significantly, and Federal general fund revenues used for highways have declined. As a result, the portion of Federal highway revenue derived from highway-user charges increased, reaching an all-time high of 96.4 percent in 1999. Since then, however, the share of Federal funding generated by highway-user charges have begun to decrease, dropping to 92.3 percent in 2006.

Exhibit 6-4 shows that the share of State government highway funding contributed by highway-user charges has generally declined over time. From 1997 to 2006, the percentage dropped from 76.3 percent to 69.0 percent. Over the same period, States grew more reliant on debt financing, as bond proceeds grew from 8.6 percent to 14.3 percent of State government highway funding.

Highway-user charges have never been as significant a source of highway revenue at the local government level as at the Federal or State levels. In recent years, the share of local government highway funding derived from highway-user charges has been slightly higher than it was historically, exceeding 8 percent each year from 2000 to 2002, before dropping to 7.6 percent in 2006.

Overall Highway Expenditures

Exhibit 6-1 indicates that total expenditures for highways in 2006 equaled $161.1 billion, then identifies the portion of this aggregate amount funded by each level of government. Exhibit 6-5 classifies this total by type of expenditure and by the level of government. The "Federal," "State," and "Local" columns in Exhibit 6-5 indicate which level of government made the direct expenditures, while "Funded by…" in the column "Current Expenditures" indicates the level of government that provided the funding for those expenditures. All amounts cited as "expenditures," "spending," or "outlays" in this report represent cash expenditures rather than authorizations or obligations.

| (Billions of Dollars) | Percent | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Federal | State | Local | Total | ||

| Capital Outlay | $0.5 | $59.0 | $19.2 | $78.7 | 48.8% |

| Funded by Federal Government* | $0.5 | $32.8 | $1.4 | $34.6 | 21.5% |

| Funded by State or Local Govt's* | $0.0 | $26.2 | $17.9 | $44.1 | 27.4% |

| Noncapital Expenditures | |||||

| Maintenance | 0.2 | 12.6 | 18.6 | 31.3 | 19.4% |

| Highway and Traffic Services | 0.0 | 4.7 | 4.4 | 9.1 | 5.7% |

| Administration | 1.5 | 7.1 | 4.6 | 13.2 | 8.2% |

| Highway Patrol and Safety | 0.0 | 7.7 | 6.8 | 14.5 | 9.0% |

| Interest on Debt | 0.0 | 4.4 | 2.2 | 6.6 | 4.1% |

| Subtotal | $1.7 | $36.5 | $36.6 | $74.7 | 46.4% |

| Total, Current Expenditures | $2.2 | $95.4 | $55.8 | $153.4 | 95.3% |

| Bond Retirement | $0.0 | $4.6 | $3.0 | $7.6 | 4.7% |

| Total All Expenditures | $2.2 | $100.1 | $58.8 | $161.1 | 100.0% |

| Funded by Federal Government* | $2.2 | $32.8 | $1.4 | $36.3 | 22.6% |

| Funded by State Governments* | $0.0 | $65.1 | $15.8 | $80.9 | 50.2% |

| Funded by Local Governments* | $0.0 | $2.2 | $41.6 | $43.8 | 27.2% |

While the Federal government funded $36.3 billion of total highway expenditures in 2006, the majority of the Federal government's contribution to highways consists of grants to State and local governments. Direct Federal spending on capital outlay, maintenance, administration, and research amounted to only $2.2 billion (about 1.4 percent). The remaining $34.1 billion was in the form of transfers to State and local governments.

| How was the $36.3 billion figure for Federal contributions to total highway expenditures derived, and why does this figure differ from amounts that appear in other documents (e.g., the President's Budget)? | |

|

The Federal expenditures shown in this report are intended to reflect the highway-related activities of all Federal agencies, rather than just those of the traditional transportation agencies such as FHWA. The figures shown in this report tie back to data in Highway Statistics,1 which are linked to data for highway expenditures on an agency-by-agency basis2 at the Federal level. These data represent cash outlays, rather than obligations (which are more relevant in terms of the annual Federal budget) or authorizations (which are more relevant in terms of multiyear authorization bills). Since the financial data reported by State and local governments are compiled on a cash basis, this report uses the same basis for Federal expenditures to ensure consistency.

The Federal figures2 rely on data from a mix of Federal, State, and local sources. In some cases, this table captures Federal funding for highways that are not otherwise tracked at the Federal level. For example, under current law, 25 percent of the receipts derived from Federal timber sales are to be paid to States for public roads and schools in the counties where forests are situated. At the time these payments are made, it is unknown what portion will ultimately be used for roads as opposed to schools; however, once States have expended these funds, they report to FHWA what portion was used for roads so that this information may be included.

Note that the Federal highway funding figures in this report exclude any amounts funded from the Highway Account of the Federal HTF that were used for transit purposes as identified in Highway Statistics.1 Such amounts would appear as Federal funding for transit in this report.

The $34.6 billion Federal contribution to total capital expenditures represents total Federal highway expenditures of $36.3 billion, less direct Federal expenditures for noncapital purposes such as maintenance on Federally owned roads, administrative costs, and research.

1 Highway Statistics, Tables HF 10 and HF-10A.

2 Highway Statistics, Tables FA-5 and FA-5R. |

|

State governments combined $32.8 billion of Federal funds with $65.1 billion of State funds and $2.2 billion of local funds to make direct expenditures of $100.1 billion (62.1 percent). Local governments combined $1.4 billion of Federal funds with $15.8 billion of State funds and $41.6 billion of local funds to make direct expenditures of $58.8 billion (36.5 percent).

Types of Highway Expenditures

Current highway expenditures can be divided into two broad categories: noncapital and capital. Noncapital highway expenditures include maintenance of highways, highway and traffic services, administration, highway law enforcement, highway safety, and interest on debt. Highway capital outlay consists of those expenditures associated with highway improvements. Such improvements include land acquisition and other right-of-way costs; preliminary and construction engineering; new construction, reconstruction, resurfacing, rehabilitation, and restoration; and installation of guardrails, fencing, signs, and signals. Bond retirement is not part of current expenditures, but it is included in the figures cited for total highway expenditures in this report.

| What basis is used for distinguishing between capital expenditures and maintenance expenditures? | |

|

The classification of the revenue and expenditure items in this report is based on definitions contained in A Guide to Reporting Highway Statistics, the instructional manual for States providing financial data for the Highway Statistics publication. This manual indicates that the classification of highway construction and maintenance expenditures should be based on criteria provided in the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials publication, AASHTO Maintenance Manual—1987.

Other definitions of maintenance are used by different organizations. Some resurfacing, restoration, and rehabilitation projects that meet this report's definition of capital outlay might be classified as maintenance activities in internal State or local accounting systems.

|

|

As shown in Exhibit 6-5, all levels of government spent $78.7 billion on capital outlay in 2006, or 48.8 percent of total highway expenditures. Highway capital outlay expenditures are discussed in more detail later in this chapter.

| How are "maintenance" and "highway and traffic services" defined in this report? | |

|

Maintenance in this report includes routine and regular expenditures required to keep the highway surface, shoulders, roadsides, structures, and traffic control devices in usable condition. This includes completing spot patching and crack sealing of roadways and bridge decks and maintaining and repairing highway utilities and safety devices such as route markers, signs, guardrails, fence, signals, and highway lighting.

Highway and traffic services include activities designed to improve the operation and appearance of the roadway. This includes items such as the operation of traffic control systems, snow and ice removal, highway beautification, litter pickup, mowing, toll collection, and air quality monitoring.

|

|

Current non-capital expenditures consumed $74.7 billion (46.4 percent), while the remaining $7.6 billion (4.7 percent) went for bond redemption. As most Federal funding for highways goes for capital items, noncapital expenditures are funded primarily by State and local governments. In 2006, spending by local governments on noncapital expenditures slightly exceeded spending by State governments on noncapital expenditures, with local governments allocating $36.6 billion and State governments spending $36.5 billion. Local government expenditures for the maintenance subset of noncapital expenditures comprised $18.6 billion (about 59.3 percent) of the $31.3 billion total.

Historical Expenditure and Funding Trends

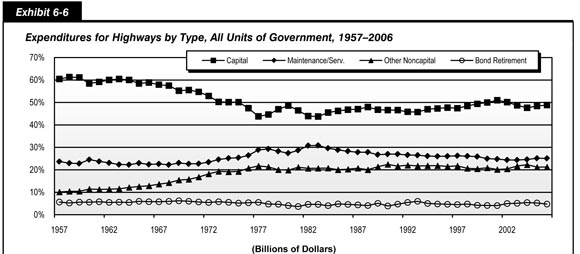

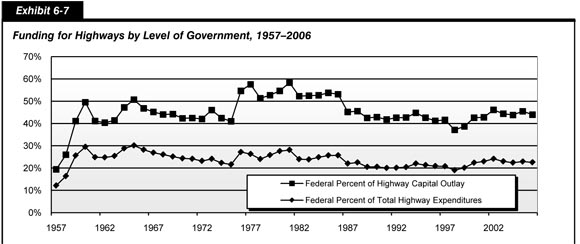

Exhibits 6-6 and 6-7 provide historical perspective for the 2006 values shown in Exhibit 6-5. Exhibit 6-6 shows how the composition of highway expenditures by all levels of government combined has changed over time. Exhibit 6-6 shows the amounts provided by each level of government to finance those expenditures and the share of funding provided by the Federal government for total highway expenditures and for highway capital outlay.

| Year | Capital Outlay | Maintenance and Services | Other Noncapital | Debt Retirement | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Administration | Highway Patrol and Safety | Interest on Debt | Total Other Noncapital | |||||

| 1957 | $5.6 | $2.2 | $0.4 | $0.3 | $0.3 | $0.9 | $0.5 | $9.3 |

| 1961 | $6.8 | $2.7 | $0.5 | $0.3 | $0.4 | $1.3 | $0.7 | $11.5 |

| 1965 | $8.4 | $3.3 | $0.8 | $0.5 | $0.5 | $1.8 | $0.9 | $14.3 |

| 1969 | $10.4 | $4.3 | $1.1 | $1.1 | $0.7 | $2.9 | $1.2 | $18.8 |

| 1973 | $12.2 | $5.9 | $1.7 | $1.9 | $1.0 | $4.7 | $1.4 | $24.2 |

| 1977 | $13.1 | $8.6 | $2.4 | $2.8 | $1.3 | $6.5 | $1.6 | $29.8 |

| 1981 | $19.7 | $12.2 | $3.4 | $3.9 | $1.7 | $9.0 | $1.6 | $42.4 |

| 1985 | $26.6 | $16.6 | $4.2 | $5.2 | $2.1 | $11.5 | $2.8 | $57.5 |

| 1989 | $33.1 | $19.0 | $5.7 | $6.6 | $2.8 | $15.2 | $3.6 | $70.9 |

| 1993 | $39.5 | $22.9 | $7.9 | $7.2 | $3.7 | $18.8 | $5.2 | $86.4 |

| 1997 | $48.4 | $26.8 | $8.3 | $9.8 | $4.2 | $22.2 | $4.6 | $102.0 |

| 1998 | $52.3 | $28.2 | $8.5 | $9.4 | $4.4 | $22.3 | $5.1 | $108.0 |

| 1999 | $57.2 | $30.0 | $9.0 | $10.4 | $4.4 | $23.7 | $4.9 | $115.9 |

| 2000 | $61.3 | $30.6 | $10.0 | $11.0 | $4.6 | $25.6 | $5.1 | $122.7 |

| 2001 | $66.7 | $32.4 | $10.2 | $11.4 | $4.8 | $26.4 | $5.3 | $130.8 |

| 2002 | $68.2 | $33.2 | $10.7 | $11.7 | $5.4 | $27.8 | $6.8 | $135.9 |

| 2003 | $70.0 | $35.0 | $12.0 | $13.5 | $5.7 | $31.2 | $7.4 | $143.6 |

| 2004 | $70.3 | $36.3 | $12.7 | $14.3 | $5.8 | $32.9 | $8.0 | $147.5 |

| 2005 | $74.1 | $38.5 | $12.0 | $14.2 | $6.3 | $32.5 | $8.0 | $153.2 |

| 2006 | $78.7 | $40.4 | $13.2 | $14.5 | $6.6 | $34.3 | $7.6 | $161.1 |

| Year | Funding for Total Highway Expenditures | Funding for Capital Outlay | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Billions of Dollars) | Percent Federal | (Billions of Dollars) | Percent Federal | |||||

| Federal | State | Local | Total | Federal | Total | |||

| 1957 | $1.1 | $6.1 | $2.0 | $9.3 | 12.2% | $1.1 | $5.6 | 19.4% |

| 1961 | $2.9 | $6.2 | $2.4 | $11.5 | 24.8% | $2.8 | $6.8 | 41.1% |

| 1965 | $4.3 | $7.3 | $2.7 | $14.3 | 30.1% | $4.2 | $8.4 | 50.7% |

| 1969 | $4.7 | $10.4 | $3.7 | $18.8 | 25.1% | $4.6 | $10.4 | 44.2% |

| 1973 | $5.8 | $13.8 | $4.6 | $24.2 | 24.1% | $5.6 | $12.2 | 46.0% |

| 1977 | $7.8 | $15.1 | $6.9 | $29.8 | 26.3% | $7.5 | $13.1 | 57.6% |

| 1981 | $11.9 | $20.1 | $10.4 | $42.4 | 28.1% | $11.5 | $19.7 | 58.4% |

| 1985 | $14.7 | $27.9 | $14.9 | $57.5 | 25.7% | $14.3 | $26.6 | 53.8% |

| 1989 | $14.5 | $36.4 | $19.9 | $70.9 | 20.5% | $14.1 | $33.1 | 42.5% |

| 1993 | $17.6 | $46.5 | $22.3 | $86.4 | 20.4% | $16.9 | $39.5 | 42.7% |

| 1997 | $21.2 | $54.2 | $26.6 | $102.0 | 20.8% | $20.1 | $48.4 | 41.6% |

| 1998 | $20.5 | $59.7 | $27.8 | $108.0 | 19.0% | $19.4 | $52.3 | 37.1% |

| 1999 | $23.3 | $61.0 | $31.7 | $116.0 | 20.1% | $22.1 | $57.2 | 38.7% |

| 2000 | $27.5 | $62.7 | $32.6 | $122.7 | 22.4% | $26.1 | $61.3 | 42.6% |

| 2001 | $30.0 | $66.3 | $34.5 | $130.8 | 23.0% | $28.5 | $66.7 | 42.8% |

| 2002 | $32.8 | $69.0 | $34.1 | $135.9 | 24.1% | $31.5 | $68.2 | 46.1% |

| 2003 | $33.0 | $71.9 | $38.7 | $143.6 | 23.0% | $31.1 | $70.0 | 44.4% |

| 2004 | $33.1 | $72.8 | $41.6 | $147.5 | 22.4% | $30.8 | $70.3 | 43.8% |

| 2005 | $35.1 | $75.3 | $42.8 | $153.2 | 22.9% | $33.7 | $74.1 | 45.5% |

| 2006 | $36.3 | $80.9 | $43.8 | $161.1 | 22.6% | $34.6 | $78.7 | 44.0% |

The increased Federal funding for highways available under the Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century (TEA-21) and the Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for Users (SAFETEA-LU) contributed to a 58.0 percent increase (from $102.0 billion to $161.1 billion in nominal dollars) in total highway spending by all levels of government between 1997 and 2006. Capital outlay by all levels of government increased by 62.7 percent in nominal dollar terms over the same period, from $48.4 billion to $78.7 billion.

The percentage of total highway expenditures that went for capital outlay peaked at 61.3 percent in 1958, the start of the Interstate era. Subsequently, capital outlay's share of total spending gradually declined to a low of 43.8 percent in 1983. As shown in Exhibit 6-6, this share climbed up above 50 percent in 2001, but has subsequently fallen back below this level. In 2006, about 48.9 percent of all highway expenditures were used for capital improvements.

Exhibit 6-7 shows that the portion of total highway funding provided by the Federal government rose from 20.8 percent in 1997 to 22.6 percent in 2006. The Federal share of capital funding also increased significantly (from 41.6 percent to 44.0 percent) over this same period. Federal cash expenditures for capital purposes increased from $20.1 billion in 1997 to $34.6 billion in 2006, while State and local capital investment increased from $28.3 billion to $44.1 billion.

Federal support for highways increased dramatically following the passage of the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 and the establishment of the HTF. The Federal share of total funding peaked in 1965 at 30.1 percent. Since that time, the Federal percentage of total funding gradually declined, dropping to a low of 19.0 percent in 1998. The Federal percentage of total funding rose steadily from 1998 until 2002 when it reached 24.1 percent, as the increased obligation authority provided under TEA-21 began to translate into higher cash outlays, but has generally declined since then. The Federally funded portion of capital outlay by all levels of government rose above 40 percent in 1959, peaking at 58.4 percent in 1981. From 1987 through 1997, the Federal share remained in a range of 41 to 46 percent. The Federal percentage of capital outlay dropped below this range in 1998, falling to 37.1 percent, but returned to this range in 2000 and has remained in it since.

| Do the relative Federal, State, and local shares of funding described in this chapter equate to a comparable relative degree of influence? | |

|

No. Significant intergovernmental transfers of funds occur from the Federal government to State and local governments, from State governments to local governments, and from local governments to State governments. Depending on the specific grant program, recipients have a varying degree of autonomy and discretion in how they use the funds. The relative degree of influence that each level of government has on what individual projects are funded and what types of highway expenditures are made is not necessarily consistent with the share of highway funding that each level of government provides. |

|

Spending by all levels of government on maintenance and traffic services increased by 51.0 percent in nominal dollar terms from 1997 to 2006, but declined as a percentage of total highway spending, since other types of expenditures grew even faster. As shown in Exhibit 6-6, maintenance and traffic services' share of total highway spending dropped to 25.1 percent. Spending on other noncapital expenditures, including highway law enforcement and safety, administration and research, and interest payments, declined from 21.8 percent of total spending to 21.3 percent. Debt retirement expenditures were the fastest-growing category of expenses between 1997 and 2006, but the rate of spending growth has declined since 2004.

| What factors have contributed to the increase in the BPI from 2004 to 2006? | |

|

The leading factors for the increase include strong growth in residential construction and global competition for construction materials. Transportation construction is one aspect of the national construction picture.

Among highway construction materials, the largest price increases have been associated with diesel fuel, steel, and concrete. Worldwide demand from China, Europe, India, and the United States has put pressure on the refining and producing capacities for these construction materials. In the United States, according to the Energy Information Agency, the transition to low-sulfur diesel fuel has affected diesel fuel production and distribution costs.

In addition to higher energy costs, a number of diverse factors are impacting construction costs. These include localized material shortages for specific construction products; consolidation in the highway industry (number of prime contractors, ownership of quarries, etc.); increased construction market opportunities in other areas, such as hurricane recovery reconstruction programs; the downsizing of the workforce due to instability of transportation funding prior to August 2005; spot shortages of skilled labor; regulatory restrictions, such as environmental permits for plants and quarries; and hurricane-related issues increasing non-highway construction demand.

|

|

Constant Dollar Expenditures

This report uses two indices for converting nominal dollar highway spending to constant dollars; the FHWA Composite Bid Price Index (BPI) is used for converting highway capital expenditures, while the Consumer Price Index (CPI) is used for converting noncapital highway spending. For some historic periods the BPI has grown faster than the CPI, while in others the CPI has grown faster. The BPI tends to be more volatile than the CPI, as it is affected by industry-specific trends as well as the general trends within the overall economy. This volatility was demonstrated in the period between 2004 and 2006, as sharp increases in the prices of materials such as steel, asphalt, and cement caused the BPI to increase by 43.3 percent, compared to a 6.7 percent increase in the CPI.

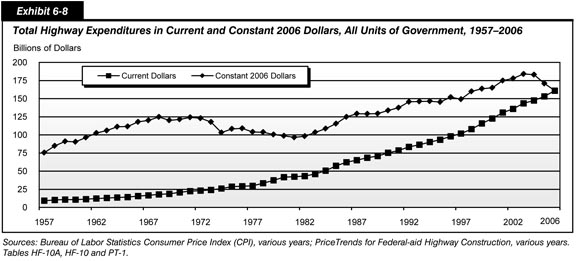

Exhibit 6-8 compares highway expenditures in current (nominal) and constant (real) dollars over time. While highway expenditures have grown in current dollar terms in each of the years from 1960 through 2006, constant dollar expenditures show a different pattern. In constant dollar terms, total highway expenditures reached a plateau in 1971, and did not keep pace with inflation from 1972 through 1981. Since 1981, constant dollar highway spending has increased; and by 1986, it had moved back above the 1971 level. Constant dollar spending reached an all time high in 2003, then dropped sharply to below 1999 levels.

Despite the recent sharp decline in the purchasing power of highway capital investment, overall highway expenditures grew more quickly than inflation between 1997 and 2006. As noted earlier, total highway expenditures increased by 58.0 percent from $102.0 billion in 1997 to $161.1 billion in 2006, which equates to an average annual growth rate of 5.2 percent in nominal terms. Over the same period, the BPI increased at an average annual rate of 6.0 percent, and the CPI increased at an average annual rate of 2.6 percent. In constant dollar terms total highway expenditures grew by 7.9 percent from 1997 to 2006, equating to an average annual growth rate of 0.8 percent.

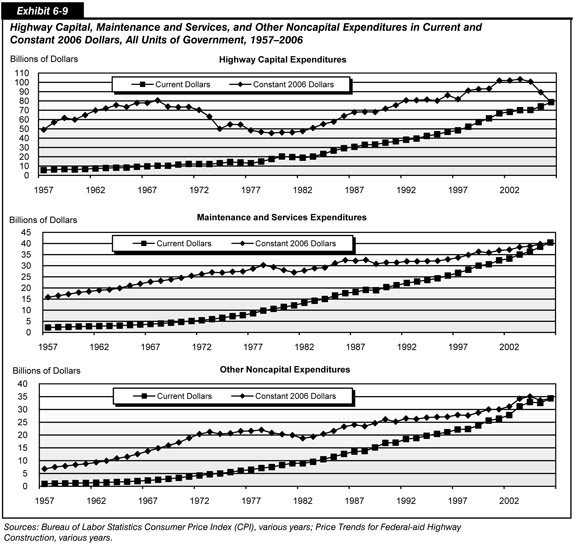

Exhibit 6-9 compares current dollar and constant dollar spending for capital outlay, maintenance and traffic services, and other noncapital expenditures (including highway law enforcement and safety, administration and research, and interest payments). As noted earlier, highway capital expenditures by all levels of government increased more quickly than noncapital expenditures, increasing 62.7 percent from $48.4 billion in 1997 to $78.7 billion in 2006, which equates to an average annual growth rate of 5.6 percent in nominal dollar terms. Because this rate of increase is smaller than the increase in the BPI over this period, highway capital expenditures fell by 4.0 percent from 1997 to 2006, equating to an average annual decline of 0.8 percent. In constant dollar terms, highway capital expenditures in 2006 were at their lowest level since 1991.

| Are the recent increases observed in the BPI unprecedented? | |

|

No. The increase in the BPI between 2004 and 2006 was of approximately the same magnitude as the increase from 1977 to 1979, and smaller than its growth from 1972 to 1974.

Other indices such as the Bureau of Labor Statistics' (BLS') Producer Price Index Industry Data for Highway and Street Construction also show large increases in this general time frame. Between 2003 and 2006, this index rose 35.3 percent, compared to a 47.7 percent increase for the same period in the BPI. Sharp increases in steel prices beginning in 2003 were followed by increases in petroleum, concrete, and other highway construction materials.

The BLS index cited above increased by an additional 5.8 percent in 2007 and 13.8 percent in 2008. However, after peaking in July 2008, the index has subsequently declined back close to its 2007 level. No 2007 or 2008 data for the BPI are available, because the index has been discontinued. A replacement index is currently being developed that will draw upon bid price data generated by States for both State-only and Federal-aid projects. The next edition of this report will utilize this new index to recalculate historic constant dollar highway expenditure data.

|

|

In constant dollar terms based on the CPI, spending for maintenance and traffic services reached an all time high in 2006, increasing 20.2 percent (2.1 percent per year) over the nine-year period beginning in 1997. Other noncapital expenditures grew by 23.1 percent (3.3 percent per year) in constant dollar terms over this same period.

Total highway expenditures funded by State and local governments, which includes a mix of capital and noncapital spending, grew by 9.6 percent (1.0 percent per year) in constant dollar terms from 1997 to 2006. Highway capital spending funded by State and local governments fell by 7.8 percent (0.9 percent per year) in constant dollar terms over this period. Expenditures funded by the Federal government, which are more heavily weighted towards capital items, grew by 2.5 percent in constant dollar terms (0.3 percent per year) from 1997 to 2006. Federally funded highway capital spending grew by 1.4 percent (0.2 percent per year) over this period.

Looking back further to 1981, the growth of capital expenditures and noncapital expenditures is more consistent in constant dollar terms. Over this 25-year period, highway capital outlay grew at an average annual rate of 5.7 percent from $19.0 to $78.7 billion in nominal dollars; in constant dollar terms this equates to a 70.0 percent increase (2.1 percent per year). Over this same period, maintenance and traffic services grew by 49.8 percent in constant dollar terms (1.6 percent per year), and other noncapital expenditures grew by 72.2 percent in constant dollar terms (2.2 percent per year).

Constant Dollar Expenditures per Vehicle Mile Traveled

While not all types of highway expenditures would necessarily be expected to grow in proportion to vehicle miles traveled (VMT), increases in VMT do increase the wear and tear on existing roads, leading to higher capital and maintenance costs. The addition of new lanes and roads to accommodate additional traffic results in one-time capital costs, as well as recurring costs for rehabilitation and maintenance. Traffic supervision and safety costs are also related in part to traffic volume. As the highway system has grown and become more complex, the cost of administering the system has grown as well.

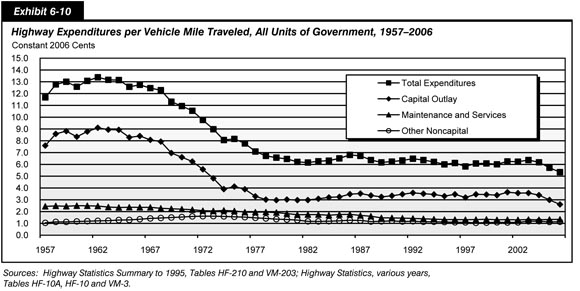

In current dollar terms, total expenditures per VMT have grown steadily over time. Between 1997 and 2006, expenditures per VMT rose from 4.0 cents to 5.3 cents. However, expenditures per VMT in constant dollars fell by 8.3 percent during this period. The initial peak in total expenditures per VMT in constant dollars during the early 1960s corresponds to the significant level of new construction and rapid Interstate Highway System expansion during that timeframe. This was followed by a steady decline in total constant dollar expenditures per VMT during the 1960s and 1970s, with the rate of decline slowing during the 1980s and early 1990s but reaccelerating after 2003. Capital outlay per VMT fell by 18.4 percent between 1997 and 2006 in constant dollar terms. Spending on maintenance and traffic services increased by 2.2 percent over this same period in terms of constant cents per VMT basis, while constant spending per VMT on other noncapital items rose 4.7 percent. These data are shown in Exhibit 6-10.

Highway Capital Outlay Expenditures

State governments directly spent $59.0 billion on highway capital outlay in 2006. Exhibit 6-11 shows how States applied this $59.0 billion to different functional systems. It also includes an estimate of how the total $78.7 billion spent by all levels of government was applied. State government capital outlay is concentrated on the higher-order functional systems, while local governments apply the larger part of their capital expenditures to lower-order systems.

| Functional Class | Direct State Capital Outlay (Billions of Dollars) | Capital Outlay, All Jurisdictions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (Billions of Dollars) | Per Lane Mile (Dollars) | Per VMT (Cents) | ||

| Rural Arterials and Collectors | ||||

| Interstate | $4.2 | $4.2 | $33,709 | 1.6 |

| Other Principal Arterial | 9.5 | 9.5 | 38,449 | 4.1 |

| Minor Arterial | 4.4 | 5.0 | 17,567 | 3.0 |

| Major Collector | 3.1 | 4.4 | 5,193 | 2.3 |

| Minor Collector | 0.4 | 1.2 | 2,343 | 2.1 |

| Subtotal | $21.6 | $24.3 | $12,009 | 2.7 |

| Urban Arterials and Collectors | ||||

| Interstate | 12.4 | 12.4 | 140,443 | 2.6 |

| Other Freeway and Expressway | 5.3 | 5.5 | 110,037 | 2.5 |

| Other Principal Arterial | 8.5 | 10.6 | 48,082 | 2.3 |

| Minor Arterial | 3.5 | 6.4 | 24,240 | 1.7 |

| Collector | 0.9 | 3.3 | 14,206 | 1.9 |

| Subtotal | $30.5 | $38.1 | $44,679 | 2.2 |

| Subtotal, Rural and Urban | $52.0 | $62.4 | $21,697 | 2.4 |

| Rural and Urban Local | $7.0 | $16.3 | $2,936 | 4.1 |

| Total, All Systems | $59.0 | $78.7 | $9,343 | 2.6 |

| Funded by Federal Government* | $32.8 | $34.6 | $4,109 | 1.1 |

Total highway capital expenditures by all levels of government amounted to $9,343 per lane mile in 2006, or 2.6 cents per VMT. Capital outlay per lane mile was generally greatest for the higher-order functional systems and was greater on urban roads than rural roads.

Capital outlay per VMT ranged from 4.1 cents on rural other principal arterials to 1.6 cents on rural Interstates. Capital outlay per lane mile was greater on urban roads than rural roads; however, when measured by VMT, outlay per VMT was greater on rural routes than urban routes. Between 2004 and 2006, capital outlay per VMT grew from 2.4 cents to 2.7 cents on rural roads, while it remained steady on urban roads at 2.2 cents.

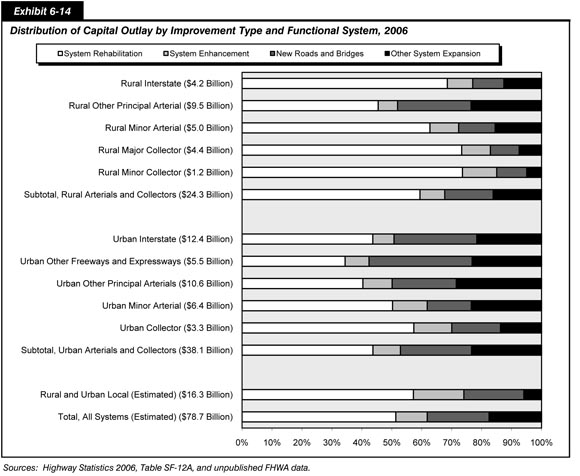

Capital Outlay by Improvement Type

States provide the FHWA with detailed data on what they spend on arterials and collectors, classifying expenditures on each functional system into 17 improvement types. For this report, these improvement types have been allocated among three groups: System Rehabilitation, System Expansion, and System Enhancement.

| How are "system rehabilitation," "system expansion," and "system enhancement" defined in this report? | |

|

System rehabilitation consists of capital improvements on existing roads and bridges that are intended to preserve the existing pavement and bridge infrastructure. These activities include reconstruction, resurfacing, pavement restoration or rehabilitation, widening of narrow lanes or shoulders, bridge replacement, and bridge rehabilitation. Also included is the portion of widening (lane addition) projects estimated to be related to reconstructing or improving existing lanes. System rehabilitation does not include routine maintenance costs. As shown in Exhibit 6-5, an additional $31.3 billion was spent by all levels of government in 2006 on routine maintenance.

System expansion includes construction of new roads and new bridges and addition of new lanes to existing roads. This includes all "New Construction," "New Bridge," "Major Widening," and most of the costs associated with "Reconstruction-Added Capacity," except for the portion of these expenditures estimated to be related to improving the existing lanes of a facility. As used in this report, "System Expansion" is the functional equivalent to "Capacity Expansion" used in some previous editions. The term was modified because some system rehabilitation and system enhancement improvements may result in added capacity without the addition of new lanes.

System enhancement includes safety enhancements, traffic operations improvements such as the installation of intelligent transportation systems, and environmental enhancements.

|

|

Exhibit 6-12 shows the distribution of the $52.0 billion in State expenditures among these three categories. Detailed data on Federal government and local expenditures are unavailable, so the combined $62.4 billion of capital outlay on arterials and collectors by all levels of government was classified based on the State expenditure patterns. Similarly, little information is available on the types of improvements being made by all levels of government on local functional system roads. To develop an estimate for the improvement type breakdown for the $78.7 billion invested on all systems in 2006, it was assumed that expenditure patterns were roughly equivalent to those observed for rural minor collectors.

| (Billions of Dollars) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| System Rehabilitation | System Expansion | System Enhancement | Total | ||

| New Roads and Bridges | Existing Roads | ||||

| Direct State Expenditures on Arterials and Collectors | |||||

| Right-of-Way | $2.0 | $1.8 | $3.8 | ||

| Engineering | $3.3 | 1.3 | 1.2 | $0.6 | 6.3 |

| New Construction | 7.5 | 7.5 | |||

| Relocation | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Reconstruction—Added Capacity | 1.8 | 4.2 | 6.0 | ||

| Reconstruction—No Added Capacity | 4.0 | 4.0 | |||

| Major Widening | 2.6 | 2.6 | |||

| Minor Widening | 0.9 | 0.9 | |||

| Restoration and Rehabilitation | 8.6 | 8.6 | |||

| Resurfacing | 0.3 | 0.3 | |||

| New Bridge | 0.8 | 0.8 | |||

| Bridge Replacement | 3.5 | 3.5 | |||

| Major Bridge Rehabilitation | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Minor Bridge Work | 1.9 | 1.9 | |||

| Safety | 1.5 | 1.5 | |||

| Traffic Management/Engineering | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| Environmental and Other | 1.4 | 1.4 | |||

| Total, State Arterials and Collectors | $25.4 | $11.5 | $10.8 | $4.3 | $52.0 |

| Total, Arterials and Collectors, All Jurisdictions (estimated)* | |||||

| Highways and Other | 23.1 | 12.1 | 12.9 | 5.5 | 53.6 |

| Bridges | 7.9 | 0.9 | 8.8 | ||

| Total, Arterials and Collectors | $31.1 | $13.0 | $12.9 | $5.5 | $62.4 |

| Total Capital Outlay on All Systems (estimated)* | |||||

| Highways and Other | 30.2 | 15.0 | 13.8 | 8.2 | 67.3 |

| Bridges | 10.1 | 1.2 | 11.4 | ||

| Total, All Systems | $40.4 | $16.2 | $13.8 | $8.2 | $78.7 |

| Percent of Total | 51.3% | 20.6% | 17.6% | 10.5% | 100.0% |

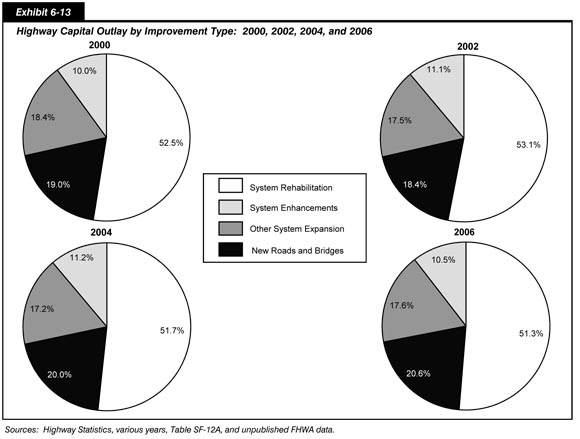

In 2006, about $40.4 billion was spent on system rehabilitation (51.3 percent of total capital outlay). As defined in this report, system rehabilitation activities include capital improvements on existing roads and bridges that are designed to preserve the existing pavement and bridge infrastructure. These improvements do not include routine maintenance.

About $16.2 billion—20.6 percent of total capital outlay—was spent on the construction of new roads and bridges in 2006. An additional $13.8 billion, or 17.6 percent, was used to add lanes to existing roads. Another $8.2 billion, or 10.5 percent, was spent on system enhancement, including safety enhancements, traffic operations improvements, and environmental enhancements.

Exhibit 6-13 depicts the change over time in the share of capital outlay devoted to these major categories. The overall share of highway capital improvements going toward system rehabilitation slightly decreased between 2000 and 2006, declining to 51.3 percent. The share devoted to system enhancements increased between 2000 and 2006, growing to 10.5 percent. Expenditures for new roads and bridges relative to other improvement expenditures increased from 19.0 percent in 2000 to 20.6 percent in 2006.

| Are the data shown in Exhibit 6-13 consistent with comparable information provided in previous editions of this report? | |

|

No. The information for 2002 and 2004 have been revised to correct errors in the underlying data for these years. In addition, the methodology used to estimate the distribution of local functional class expenditures was modified for each of the years depicted in the exhibit. As a result of this change, the estimated percentages for system enhancements and new roads and bridges increased, while the estimated percentages for other system expansion and system rehabilitation decreased.

|

|

Exhibit 6-14 shows significant variations in the types of capital expenditures made by States on different functional systems. The portion of capital outlay devoted to system rehabilitation ranges from 34.4 percent on urban other principal arterials to 73.6 percent on rural major collectors. Overall, system rehabilitation's share on arterials and collectors in rural areas (59.4 percent) was greater than in urban areas (43.7 percent).

System expansion expenditures also vary significantly by functional class. The portion of capital used for construction of new roads and bridges is highest on urban other freeways and expressways, at 34.4 percent, while urban other principal arterials have the largest share going to other system expansion improvements, at 28.5 percent. Urban other freeways and expressways have over 57.6 percent of capital investment devoted to system expansion).

Constant Dollar Expenditures by Improvement Type

As noted earlier, inflation has greatly reduced the relative purchasing power of transportation dollars. Between 1997 and 2006, highway capital outlay expenditures declined by 4.0 percent in constant dollar terms. Investment in system expansion—such as the widening of roads and the construction of new facilities—decreased by 14.2 percent in constant dollar terms, reflecting the increased cost of materials. At the same time, spending on other improvements increased. In constant dollar terms, investment in system enhancement increased by 22.7 percent, while funding for system rehabilitation grew by 0.4 percent.

Capital Outlay on the National Highway System

The National Highway System (NHS), which is described more fully in Chapter 2, includes the Interstate Highway System and other roads important to the nation's economy, defense, and mobility. Exhibit 6-15 identifies the distribution of the $37.1 billion of capital outlay on the NHS in 2006 by functional system. Approximately $13.5 billion was invested on rural arterials and collectors that year, and another $23.3 billion was spent on urban arterials and collectors. An estimated $0.3 billion was spent on NHS routes functionally classified as rural local or urban local, which would mainly consist of intermodal connectors and STRAHNET Connectors.

| Functional Class | Total (Billions of Dollars) | Percent of Total NHS |

|---|---|---|

| Rural Arterials and Collectors | ||

| Interstate | $4.2 | 11.3% |

| Other Principal Arterial | $8.2 | 22.1% |

| Minor Arterial | $0.6 | 1.7% |

| Major Collector | $0.4 | 1.2% |

| Minor Collector | $0.0 | 0.0% |

| Subtotal | $13.5 | 36.3% |

| Urban Arterials and Collectors | ||

| Interstate | $12.4 | 33.3% |

| Other Freeway and Expressway | $4.9 | 13.3% |

| Other Principal Arterial | $5.5 | 14.7% |

| Minor Arterial | $0.4 | 1.2% |

| Collector | $0.2 | 0.4% |

| Subtotal | $23.3 | 62.9% |

| Subtotal, Rural and Urban | $36.8 | 99.2% |

| Rural and Urban Local | $0.3 | 0.8% |

| Total, All Systems | $37.1 | 100.0% |

Exhibit 6-16 categorizes capital spending on the NHS by type of improvement. System rehabilitation expenditures of $16.6 billion constituted 44.7 percent of total NHS capital spending in 2006. The $17.7 billion spent for system expansion represented 47.7 percent of total NHS capital spending, while the $2.8 billion spent for NHS system enhancement constituted 7.6 percent. Between 2004 and 2006, there was an increase in the relative share of spending directed to NHS rehabilitation projects (up from 43.5 percent), an increase in the share of spending for NHS expansion (up slightly from 47.6 percent), and a decrease in the share of spending for NHS enhancement (down from 8.9 percent).

| Total Invested (Billions of Dollars) |

Total NHS Capital Spending | NHS Percent of Total Capital Expenditures for All Highways | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rural | Urban | Total | Rural | Urban | Total | ||

| System Rehabilitation | |||||||

| Highway | $6.0 | $6.2 | $12.3 | 33.1% | 19.7% | 20.3% | 40.1% |

| Bridge | $1.1 | $3.2 | $4.3 | 11.6% | 9.2% | 26.4% | 35.6% |

| Subtotal | $7.2 | $9.4 | $16.6 | 44.7% | 16.7% | 22.0% | 38.8% |

| System Expansion | |||||||

| Additions to Existing Roadways | $2.6 | $5.5 | $8.1 | 21.8% | 18.8% | 39.7% | 58.5% |

| New Routes | $2.6 | $6.3 | $8.9 | 24.0% | 19.1% | 46.2% | 65.3% |

| New Bridges | $0.1 | $0.6 | $0.7 | 1.9% | 13.2% | 57.0% | 70.1% |

| Subtotal | $5.3 | $12.3 | $17.7 | 47.7% | 18.8% | 43.4% | 62.2% |

| System Enhancements | $1.0 | $1.8 | $2.8 | 7.6% | 12.9% | 24.7% | 37.6% |

| Total Investment | $13.5 | $23.6 | $37.1 | 100.0% | 17.1% | 30.0% | 47.1% |

The $37.1 billion spent for capital improvements to the NHS in 2006 constituted 47.1 percent of the $78.7 billion that all governments expended on highway capital projects that year. Approximately 38.8 percent of total highway rehabilitation investment on all roads was directed toward the NHS, including 16.7 percent directed toward rural NHS routes and 22.0 percent directed toward urban NHS routes.

Of total highway system expansion investment on all roads in 2006, approximately 62.2 percent was directed toward the NHS, including 18.8 percent directed toward rural NHS routes and 43.4 percent directed toward urban NHS routes. Approximately 37.6 percent of total capital expenditures classified as system enhancements in 2006 were directed toward NHS routes.

Capital Outlay on the Interstate Highway System

Of the $37.1 billion spent by all levels of government for the capital improvements to the NHS in 2006, 44.6 percent was used on the Interstate component of the NHS. Exhibit 6-17 describes how the $16.5 billion of Interstate capital spending in 2006 was distributed by type of improvement. In 2006, all levels of government combined directed 49.9 percent of their Interstate-related expenditures to system rehabilitation, 42.6 percent to system expansion, and 7.4 percent to system enhancement. Between 2004 and 2006, there was a decrease in the relative share of spending directed to Interstate rehabilitation projects (down from 50.8 percent), an increase in the share of spending for Interstate expansion (up from 40.9 percent), and a slight increase in the share of spending for Interstate enhancement (up from 8.3 percent).

| Total Invested (Billions of Dollars) |

Percent of Total Interstate Capital Spending | Percent of Total for All Functional Classes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rural | Urban | Total | Rural | Urban | Total | ||

| System Rehabilitation | |||||||

| Highway | $2.5 | $3.2 | $5.8 | 34.8% | 8.3% | 10.5% | 18.8% |

| Bridge | $0.3 | $2.2 | $2.5 | 15.1% | 2.8% | 17.9% | 20.7% |

| Subtotal | $2.9 | $5.4 | $8.3 | 49.9% | 6.7% | 12.6% | 19.3% |

| System Expansion | |||||||

| Additions to Existing Roadways | $0.5 | $2.7 | $3.2 | 19.4% | 3.8% | 19.4% | 23.2% |

| New Routes | $0.4 | $3.1 | $3.5 | 21.3% | 3.0% | 22.8% | 25.8% |

| New Bridges | $0.0 | $0.3 | $0.3 | 1.9% | 2.6% | 29.9% | 32.6% |

| Subtotal | $1.0 | $6.1 | $7.1 | 42.6% | 3.4% | 21.4% | 24.8% |

| System Enhancements | $0.4 | $0.9 | $1.2 | 7.4% | 4.7% | 11.7% | 16.4% |

| Total Investment | $4.2 | $12.4 | $16.5 | 100.0% | 5.3% | 15.7% | 21.0% |

Exhibit 6-18 examines these changes in greater detail. Most notably, increased funding for Interstate expansion projects was targeted in urban areas. Between 2004 and 2006, there was a 39.7 percent increase in spending for system expansion projects on urban Interstates, and a 22.6 percent decline in Interstate expansion activities in rural areas. Overall, between 2004 and 2006, there was a 26.2 percent increase in capital spending on urban Interstates, and a 7.5 percent increase on rural Interstates.

| 2004 (Billions of Dollars) | 2006 (Billions of Dollars) |

Percent Change 2006/2004 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rural | Urban | Total | Rural | Urban | Total | Rural | Urban | Total | |

| System Rehabilitation | |||||||||

| Highway | $1.9 | $2.8 | $4.7 | $2.5 | $3.2 | $5.8 | 31.4% | 16.6% | 22.7% |

| Bridge | $0.4 | $1.8 | $2.3 | $0.3 | $2.2 | $2.5 | -21.1% | 18.3% | 10.8% |

| Subtotal | $2.4 | $4.6 | $7.0 | $2.9 | $5.4 | $8.3 | 21.9% | 17.3% | 18.8% |

| System Expansion | |||||||||

| Additions to Existing Roadways | $0.7 | $2.2 | $2.9 | $0.5 | $2.7 | $3.2 | -24.2% | 21.4% | 10.5% |

| New Routes | $0.5 | $2.0 | $2.5 | $0.4 | $3.1 | $3.5 | -19.5% | 57.1% | 41.4% |

| New Bridges | $0.0 | $0.2 | $0.2 | $0.0 | $0.3 | $0.3 | -32.5% | 73.6% | 54.1% |

| Subtotal | $1.2 | $4.4 | $5.6 | $1.0 | $6.1 | $7.1 | -22.6% | 39.7% | 25.9% |

| System Enhancements | $0.3 | $0.8 | $1.1 | $0.4 | $0.9 | $1.2 | 19.2% | 5.1% | 8.8% |

| Total Investment | $3.9 | $9.8 | $13.7 | $4.2 | $12.4 | $16.5 | 7.5% | 26.2% | 20.9% |

It is important to note that, for any particular functional class (such as rural Interstates) and any particular type of capital improvement (such as the bridge component of system rehabilitation), year-to-year spending is much more variable than for total capital investment of all types. Year-to-year investment can be more easily affected by large individual projects that happen to have a high level of cash outlays in a given year. The changes in expenditure patterns observed between 2004 and 2006, therefore, may not represent a long-term trend. This comparison is included primarily to help put into perspective the comparisons of 2006 spending with the future capital investment scenarios discussed in Part II of this report.

Innovative Finance

In recent years, governments throughout the United States have experimented with new ways of financing transportation projects. As costs have increased for many of these projects, officials have often tried to replicate some of the most successful strategies of the private sector. Some officials have taken this approach much further, engaging the private sector as an active partner in delivering projects. As a result, innovative finance is a far more advanced element of transportation policy than it was 5 or 10 years ago. This section describes how innovative finance is complementing traditional methods of paying for the Nation's surface transportation projects.

Innovative finance includes a combination of specially designed techniques that aid traditional funding methods in providing financing for transportation projects. These techniques open up new streams of revenue, helping to retire debt obligations; and reduce financing and related costs, freeing up savings for other projects. While these methods are commonly used in the private sector, they are relatively new to Federally aided transportation funding.

Innovative finance concepts have evolved over time. The Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act (ISTEA) and TEA-21 laid the foundations for several new concepts designed to fund transportation investment. SAFETEA-LU has continued the development of innovative financing mechanisms. SAFETEA-LU advanced the use of Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs), credit assistance, and innovative debt financing as tools in transportation finance.

Public-Private Partnerships

There is a long history of the private sector providing transportation service. In the late 1700s and early 1800s, private toll roads opened the interior United States to commerce and settlement. More recently, commercial and residential developers have helped finance local roads so that new projects could be built. These developers have either built the roads themselves, or paid impact fees that local governments used to complete new routes.

While private sector investment has slowed somewhat since the advent of public financing for highways, there has been renewed interest in private sector involvement as transportation budgets have been stretched. Additionally, private sector arrangements are central to many projects that involve freight transportation, since nearly all service providers and many elements of freight infrastructure are private.

| Are PPPs limited to the transportation sector? | |

|

No. PPPs are used regularly in several sectors, including water and wastewater, education, health care, corrections, parks and recreation, and technology.

|

|

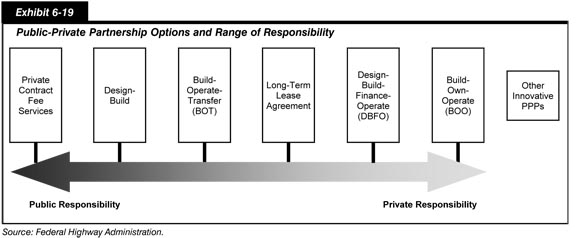

Today, a variety of public-private partnerships (PPPs) are being used to provide transportation services. A public-private partnership is a broad term that refers to contractual agreements formed between public and private sector partners. Under this arrangement, the private sector steps out of its traditional role and becomes more active in making decisions as to how a project will be accomplished.

Public-private partnerships can be applied to a large range of transportation functions across all modes. These functions may include project conceptualization, design, finance, construction, maintenance, toll collection, and project maintenance. Exhibit 6-19 describes the more common PPP options currently being used in the United States. It shows how the range of responsibilities shifts from the public to the private sectors depending on different PPP options, which are described below. Exhibit 6-20 provides a list of the PPPs being implemented across the United States, either on existing facilities or new capacities.

| PPP | Location | Status |

|---|---|---|

| Existing Facility | ||

| Chicago Skyway | Illinois | Closed |

| Indiana Toll Road | Indiana | Closed |

| Pocahontas Parkway | Virginia | Closed |

| Northwest Parkway | Colorado | Closed |

| Dulles Greenway | Virginia | Closed |

| Pennsylvania Turnpike | Pennsylvania | Request for Quotation (RFQ) Issued |

| Greenville Southern Connector | South Carolina | RFQ Issued |

| New Capacity * | ||

| Trans-Texas Corridor (TTC) -35 | Texas | Concession Awarded |

| SH-130 Segments 5 and 6 | Texas | Closed |

| I-69/TTC | Texas | Request For Proposals (RFP) Issued |

| I-635 | Texas | RFP Issued |

| North Tarrant Express | Texas | Bidders Shortlisted |

| Dallas/Fort Worth (DFW) Connector | Texas | Bidders Shortlisted |

| SH-161 | Texas | Bidders Shortlisted |

| US-281/Loop 1604 | Texas | Bidders Shortlisted |

| Capital Beltway High-Occupancy Toll (HOT) Lanes | Virginia | Closed |

| I-95/I-395 HOT Lanes | Virginia | Interim Agreement Executed |

| US Route 460 | Virginia | Bidders Shortlisted |

| Midtown Corridor Tunnel | Virginia | Expressions of Interest Submitted |

| Port of Miami Tunnel | Florida | Preferred Bidder Selected |

| I-595 Improvements | Florida | Bidders Shortlisted |

| First Coast Outer Beltway | Florida | RFQ Issued |

| Northwest Corridor | Georgia | Development Agreement Executed |

| I-285 Northwest Truck-Only Toll (TOT) Lanes | Georgia | Evaluation of Proposers |

| GA-400 Crossroads Region | Georgia | Evaluation of Proposal |

| I-20 Managed Lanes | Georgia | Pre-Solicitation |

| Missouri Safe and Sound Bridge Program | Missouri | Preferred Bidder Selected |

| Oakland Airport Connector | California | RFP Issued |

| Knik Arm Crossing Project | Alaska | Bidders Shortlisted |

| Denver Regional Transportation District (RTD) | Colorado | RFQ Expected |

| I-73 | South Carolina | Request for Conceptual Proposals |

Private Contract-Fee Services

Many public agencies are transferring responsibility for services they would typically perform to private sector companies. Agencies that use private contract-fee services can tap private sector technical, management, and financial planning expertise in new ways. This often reduces the work burden for agency staff, and it can provide access to innovative technology and specialized expertise. Maintenance, operations, and finance are three areas where this approach is often used.

As an example of this model, the South Carolina Department of Transportation has implemented a statewide program to accelerate the completion of 200 highway improvement projects in 7 years, instead of 27. Because the State did not want to add new personnel, the Department of Transportation entered into partnerships with two private construction and resource management firms. It was agreed that these companies would work on strategic planning, financial management, design, and construction activities.

Design-Build

With the second model, Design-Build delivery, design and construction phases are merged into a single contract. The design-builder assumes responsibility for the majority of the design work and all construction activities, together with the risks associated with providing these services, for a fixed fee. When using Design-Build delivery, owners usually retain responsibility for financing, operating, and maintaining the project. While Design-Build procurement has been more prevalent in private sector work, it is also gaining acceptance among many public agencies. SAFETEA-LU advanced the use of Design-Build delivery by eliminating an FHWA requirement that prohibited agencies from issuing requests for proposals and entering into contracts until after environmental approval. This had been a particular problem for PPPs, since there are many advantages in having the private sector partner involved in the environmental review process.

| The 2006 edition of the C&P report listed the Design-Bid-Build model on the continuum of public-private partnerships. Why has it been removed from this edition of the report? | |

|

The Federal government does not consider the Design-Bid-Build model a PPP because it fails to go beyond the "traditional" arrangement for implementing projects.

The Design-Bid-Build model was used for much of the Twentieth Century. A Design-Bid-Build model segregates design and construction responsibilities by awarding them to an independent private engineer and a separate private contractor. The delivery process is separated into three linear phases: (1) design, (2) bid, and (3) construction. During the initial design phase, a transportation agency awards a design contract to an engineer or architect, who completes a final project design and supporting documentation. In the second phase, the owner uses this documentation to assemble construction bid documents. Pre-qualified contractors are invited to submit competitive, lump-sum bids; and the owner awards the construction contract to the contractor submitting the lowest responsible bid or total contract price. In the construction phase that follows, the owner retains responsibility for monitoring the contractor's performance.

|

|

Alaska's Anton Anderson Memorial Tunnel is an example of both the private contract-fee service model and the Design-Build model. To convert the former railroad tunnel for both rail and highway use, the Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities awarded a Design-Build contract. Once the project was finished, the State outsourced the operation of the tunnel to a private highway asset management and operations company. Since the tunnel opened in 2000, that firm's responsibilities have included toll collection and administration, emergency response, snow removal, maintenance, and the complex procedures by which the tunnel switches between train and automobile use.

Build-Operate-Transfer/Design-Build-Operate-Maintain

The third model, "turnkey procurement," is more formally known as Build-Operate-Transfer (BOT)/Design-Build-Operate-Maintain (DBOM). This approach combines responsibility for usually separate functions—design, construction, and operations and maintenance—under a single entity. One advantage of this approach is that the private sector team is required to establish a long-term maintenance program up front, together with estimates of the associated costs. This might reduce the likelihood that problems with the physical performance of the infrastructure asset will go unnoticed, saving money in the long run.

Recent improvements to Massachusetts Route 3 were completed through a BOT/DBOM contract. Under a traditional public process, the improvements would have required five different contract packages and taken 12 to 15 years to complete. Instead, the State used a BOT/DBOM approach, cutting the construction time in half. Through a competitive process, the Massachusetts Highway Department selected a private developer to finance, design, and build the project, then operate and maintain the facility for 30 years. The developer may generate nonproject revenues through ancillary development in the corridor. The developer also shares in the sale of fiber optic rights and the sublease of a service plaza.

Long-Term Lease Arrangements

The fourth model, that which is used in long-term lease arrangements, involves the leasing of an existing, publicly financed toll facility to a private sector concessionaire for a certain period of time. The transportation agency awards long-term leases on a competitive basis, picking the most attractive offer. The amount of the concession fee is typically the most important factor, but other criteria may include the length of the concession period and the creditworthiness and professional qualifications of the bidders. Once the award is made, the concessionaire pays the upfront concession fee, then has the right to collect tolls on the facility for a specified time period. In exchange, the private partner must operate and maintain the road, often making improvements.

Long-term lease arrangements are among the most visible, hotly debated innovations in transportation today. Supporters argue that long-term leases are among the fastest ways to improve transportation services in an era when public funding is limited and citizens are often reluctant to pay higher taxes. By transferring toll setting responsibilities to the private sector, they argue, the process is depoliticized. They also argue that the large, up-front concession fees can be used to fund badly needed transportation projects elsewhere. Opponents of long-term lease arrangements, however, claim that the public can lose control over toll rates, and that tolls may become potentially burdensome. Opponents also argue that, in the long run, the public agency loses a consistent stream of revenue.

| What terms and conditions can help preserve some public control over facilities that are part of long-term lease arrangements? | |

|

There are several ways a long-term lease arrangement can be structured to preserve some public control. Transportation agencies can provide oversight of the private sector partner's performance, and require specific capital reinvestment, safety, and customer services requirements in their lease agreements. Other regulations can be enacted to ensure that the lease proceeds are used to support transportation improvements in prescribed areas. Provisions can also be incorporated requiring sharing of excess revenues between the public and private entities if toll revenues exceed some predetermined level. |

|

Over the past several years, there have been several high-profile long-term lease arrangements. In 2005, the City of Chicago announced that it had entered into an agreement with a consortium to lease the 7.8-mile Chicago Skyway Toll Bridge System for 99 years. Under the lease agreement, the consortium paid the City of Chicago $1.83 billion for the right to operate and collect tolls on the Chicago Skyway. The privatization of the Skyway, an existing toll road, was the first agreement of its kind in the United States. The lease agreement established maximum toll rates and set facility performance standards. The consortium is responsible for all operating and maintenance costs of the Skyway and will have the right to all toll revenue. In this particular example, the toll road concession revenues were treated as general revenues to the city, rather than being dedicated to highway or transit improvements.

In 2006, the same consortium entered into an agreement with the Indiana Finance Authority to take over operations of the 157-mile Indiana Toll Road for the next 75 years. The concession agreement established toll rates and possible increases, and it placed limits on the return on investment for the concessionaire. The $3.8 billion concession fee will provide funding for about 200 transportation projects around the State, including the construction of Interstate 69 between Evansville and Indianapolis.

Also in 2006, the Virginia Department of Transportation executed agreements to turn over the Pocahontas Parkway to a private concessionaire for 99 years. Under the terms of those agreements, the concessionaire acquired the sole right to enhance, manage, operate, maintain, and collect tolls on the Parkway. The $548 million concession fee relieved the Virginia Department of Transportation from all debt related to the construction of the Pocahontas Parkway. This arrangement—combined with credit from the Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (TIFIA) program—will also lead to the construction of a four-lane extension to Richmond International Airport.

All three of these projects involved foreign investors. The PPP markets in Europe and Australia are more mature than those in the United States, and experienced investors from both continents are actively seeking out new opportunities in the United States. Several American financial institutions, however, are now establishing infrastructure investment funds. The new authority provided by SAFETEA-LU to issue tax exempt private activity bonds for transportation projects may encourage American investors to expand their activity in the domestic toll road market.

| How have other countries used PPPs to provide transportation services? | |

|

PPPs are central to the transportation policies of several European countries. In these countries, highway agencies are beginning to take on the role of network operator rather than provider of services.

The United Kingdom has some of the most extensive experience with PPPs, where they became popular in the early 1990s as local governments struggled with maintenance and reconstruction costs. Improvements were often delayed and, when construction finally began, limited public funds meant that completion was often delayed. Since that time, the use of PPPs has proven to be a remarkable remedy. A survey by the United Kingdom Treasury showed that of 61 PPP projects, nearly 90 percent were completed early or on time. Projects that were not completed on time were completed within three months of the scheduled date.

In France, long-term lease arrangements have been used for more than three decades. Portugal is aggressively using long-term lease arrangements as part of its long-term transportation strategic plan, and eventually aims to have 90 percent of its national network administered by concessions.

|

|

Design-Build-Finance-Operate

The fifth model, the Design-Build-Finance-Operate (DBFO) approach, bundles together all design, construction, finance, and operation activities, transferring these functions to private sector partners. There is a great deal of variety in DBFO arrangements in the United States, especially in the degree to which financial responsibilities are actually transferred to the private sector. One commonality among all DBFO projects is that they are either partly or wholly financed by debt leveraging revenue streams dedicated to the project. Tolls are the most common revenue source; however, other finance mechanisms may include lease payments and vehicle registration fees. Future revenue is leveraged to issue bonds or other debt that provides funds for capital and project development costs. They are also often supplemented by public sector grants, either through direct funding or in-kind contributions such as donations of right-of-way. In some cases, private partners are required to make equity investments as well.

One example of a DBFO project is California State Road 125, commonly known as the South Bay Expressway. This connects the only commercial port of entry in San Diego to the regional freeway network. The southern section of S.R. 125, stretching about ten miles, was constructed as a privately financed and operated toll road with electronic toll collection. A limited partnership holds a franchise with the State under which it financed and built the highway. When the road was finished in 2007, the State took ownership, but the limited partnership leased the facility back from the State. The limited partnership will operate and maintain the road for five years. After that period, control will revert to the State at no cost.

Build-Own-Operate

The sixth model, Build-Own-Operate (BOO), completely removes the public sector from the transportation project. Under this approach, a private company is granted the right to develop, finance, design, build, own, operate, and maintain a transportation project, owning the project outright and retaining the operating revenue risk and all of the surplus operating revenue. This approach is most common in the power and telecommunications industries.

A major section of the Foley Beach Express was built using BOO principles. This limited access, four-lane route stretches for about 14 miles in southern Alabama. Six miles of the route—including a major bridge over the Intracoastal Waterway—were completely financed, designed, and constructed by a private company. The company operates and maintains the facility today.

Other Public-Private Partnerships

There are some types of PPPs that do not necessarily correspond to the six models outlined above. They demonstrate the variety of ways in which the public and private sectors can meet modern transportation needs.

Construction of a major section of the King Coal Highway involves an innovative partnership between the West Virginia Department of Transportation, a local redevelopment authority, and coal companies. The State is using excess materials generated by the mining process to construct the foundation for the highway. Because regulatory agencies are more likely to allow permits for coal removal if there is a constructive use for excess material, coal companies have benefited from this level of participation. It is estimated that this collaborative process has cut costs by 50 percent for the initial section of the highway.

| How has the U.S. Department of Transportation advanced the use of PPPs? | |

|

In the last few years, the U.S. Department of Transportation has implemented several initiatives to help remove barriers and increase the role of the private sector in highway construction, operation, and maintenance.