U.S. Department of Transportation

Federal Highway Administration

1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE

Washington, DC 20590

202-366-4000

Publication No. FHWA-PL-17-011

January 2017

At this point, FHWA has distributed Federal funds (but not cash) to the States as prescribed by the authorization act. This chapter discusses how long those funds remain available to the State and what happens if the State does not use the funds in a timely manner. It also describes the Federal share of a project’s cost and the commitment of the Federal government to pay a State for the Federal share of its eligible expenses. Finally, the chapter covers the Federal budget process and appropriations legislation.

An obligation is a legal commitment: the Federal government’s promise to pay a State for the Federal share of a project’s eligible cost. This commitment occurs when FHWA approves the project and executes the project agreement.[38] Obligated funds are considered “used” even though no cash is transferred.

Obligation also is the step in the funding process under contract authority programs where Congress most commonly imposes budgetary controls. This usually involves the imposition of limitations on Federal-aid Highway Program (FAHP) obligations. Chapter 5 describes these limitations.

Period of availability. Funding for many Federal programs terminates at the end of the fiscal year for which it is appropriated. Federal-aid highway funds, in contrast, are typically available for obligation (use) for more than one year. When FHWA makes a new apportionment or allocation for an ongoing program, it adds that amount to the program’s unused balance from previous years. If, in an authorization act, Congress chooses to discontinue a program, any unused balance continues to be available for the period of availability that originally applied to the discontinued program.

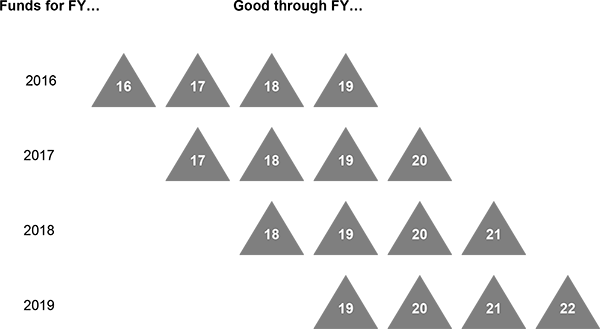

Some types of funds—known as “no-year” or indefinite funds—are available until they are expended. However, as specified in law, under most of the major Federal-aid highway programs, funds are available for obligation “…for a period of three years after the last day of the fiscal year for which the funds are authorized…”;[39] thus, they are available for obligation for four years. For example, fiscal year (FY) 2016 Federal-aid highway funds that FHWA apportioned on October 1, 2015, are available for obligation until September 30, 2019. Note that outlays (expenditures) associated with timely-obligated funds may occur beyond the four-year obligation period.

Figure 4 shows the typical period of availability of funding for Federal-aid highway funding.

Figure 4. Typical period of availability for Federal-aid highway funding.

Lapsing. If FHWA does not obligate a particular year’s funding (at the request of the State or other funding recipient) within the period of availability, the authority to obligate any remaining amount lapses—it is no longer available.[40] Since the lapse is of funding (budgetary resources), rather than cash, a State does not need to return any cash to the Federal government at that time; it simply has lost the opportunity to obligate the lapsed amount.

When obligating funds, FHWA uses a “first-in, first-out” method. This method assumes that the oldest funds in a given category are obligated first, minimizing the risk of a funding lapse. States also manage their use of FAHP funding to reduce the likelihood of lapsing.

The Federal government typically does not pay for the entire cost of construction or improvement of Federal-aid highways. Therefore, the State or local project sponsor must usually “match” Federal funds with funds from other sources. The maximum share of an eligible project’s costs that the Federal government will cover is known as the Federal share. In almost all cases a State may, at its option, reduce the Federal share for a particular project by contributing more non-Federal resources than required by law.

Federal share percentages. Unless otherwise specified in the authorizing legislation, most projects will have an 80 percent Federal share.[41] However, a number of statutory provisions can modify a program’s basic Federal share. Examples include the following:

Interstate System. The Federal share for projects on the Interstate system is 90 percent (unless the project adds lanes that are not high-occupancy-vehicle or auxiliary lanes, in which case the Federal share will revert to the 80 percent level).[42]

Sliding scale. States with large amounts of Federal lands have their Federal share of certain programs increased up to 95 percent in relation to the percentage of their total land area that is under Federal control.[43]

100 percent Federal funding. Certain programs, such as the Federal Lands Transportation Program, the Tribal Transportation Program, and the Territorial Highway Program, provide a 100 percent Federal share for projects. In other cases, programs provide full Federal funding to support specific types of projects, such as Emergency Relief projects (for certain emergency repairs made within 180 days of the event causing the need for such repairs),[44] Highway Use Tax Evasion projects,[45] and certain safety projects.[46] The FAST Act also offered a Federal share of up to 100 percent for projects with innovative project delivery methods.[47]

Tapered Match. In some cases, FHWA may approve a “tapered” match for a project. Under tapered match, the Federal share may vary on individual progress payments on a project, as long as the total contribution of Federal funds does not exceed the maximum Federal share authorized for the project.[48] These progress payments are permitted as long as a project agreement has been executed pursuant to 23 U.S.C. 106.[49]

Appendix H shows the basic Federal share for selected programs, along with provisions that may modify that share.

Sources of matching funds. The funds required to match Federal funding can come from any or all of the following sources:

An appropriations act is a congressional action that makes funds available for obligation and expenditure with specific limitations as to amount, purpose, and duration. As described in Chapter 2, most Federal programs are funded through appropriated budget authority, courtesy of an appropriations act. However, as the FAHP operates under contract authority, the appropriations act serves a different function for FHWA.

Four elements of an appropriations act most significantly impact the Federal-aid Highway Program:

To become law, an appropriations bill must pass through each of the steps required on an authorization bill (see “From bill to law” in Chapter 2). The appropriations process differs from the authorization process in three substantial ways, though. First, an appropriations bill is an outcome of the broader Federal budget process, where it is preceded by the President’s Budget request and a congressional budget resolution. Second, an appropriations bill falls under the jurisdiction of different congressional committees than an authorization bill. Third, based on long-standing precedent, an appropriations action must originate in the House of Representatives, rather than the Senate. An authorization bill, in contrast, may originate in either of the two chambers.

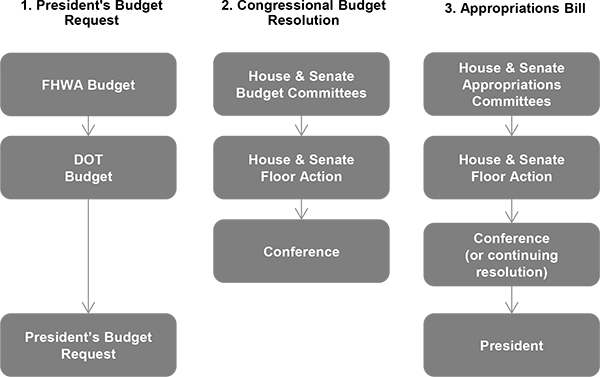

As shown in figure 5, the Federal budget process has three main phases. First, the Administration prepares and submits to Congress the President’s Budget request. Next, through a congressional budget resolution, the House and Senate agree on the total amount of Federal spending for the fiscal year. Finally, the two chambers develop and pass one or more appropriations bills, consistent with the constraints set by the budget resolution. These bills go to the President, who signs them into law.

Figure 5. Federal budget process.

President’s Budget request. The executive branch begins the Federal budget process by developing the President’s Budget request. FHWA typically starts developing its portion of the budget in the spring, about 1½ years before the beginning of the fiscal year being addressed. Among its contents, the FHWA budget includes a proposal for each of the following:

Chapter 5 discusses the obligation limitation. Chapter 6 describes liquidating cash and the projections on which the Administration relies when requesting the amount for a fiscal year.

Typically in June, FHWA submits its budget proposal to the Office of the Secretary of Transportation. The Department reviews FHWA’s budget proposal and provides any changes in a process known as “passback”. FHWA may appeal the passback, though the Department makes the final determinations. The Department then incorporates FHWA’s proposal, as revised via passback, into the broader departmental budget, then submits that budget to the Office of Management and Budget (OMB).

Once all of the executive agencies have developed their respective budgets and have the approval of OMB (including a second passback process), the budgets become part of the President’s Budget request. By law, the President must submit his or her budget request to Congress on or before the first Monday in February, less than nine months before the fiscal year begins. The Constitution grants Congress the “power of the purse”—the authority and responsibility to pass laws that govern Federal spending—and the President’s budget is simply a proposal. Nonetheless, throughout the appropriations process the President will frequently state his or her position on the budget legislation under consideration in Congress.

Committees of jurisdiction. As with the authorizing process, Congress is divided into committees of jurisdiction for developing the budget of the United States, including both the Congressional budget resolution and the annual appropriations bills.

The House and the Senate each have a Committee on the Budget. These committees, established by the 1974 Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act, are charged with drawing up budget resolutions and shepherding them through the respective chambers.

The House and Senate also each have a Committee on Appropriations, which is responsible for developing appropriations legislation. Each of these committees has twelve subcommittees, and each of those subcommittees produces an appropriations bill for its area of jurisdiction—yielding a total of 12 appropriations bills per year. Appropriations legislation for transportation (including FHWA) is under the primary jurisdiction of each chamber’s subcommittee on Transportation, Housing and Urban Development, and Related Agencies (THUD).

Table 4 shows the relevant committees of jurisdiction.

| HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES | |

|---|---|

| Committee | Jurisdiction |

| Committee on the Budget | Congressional Budget Resolution |

| Committee on Appropriations | All appropriations |

| Subcommittee on Transportation, Housing and Urban Development, and Related Agencies (THUD) | THUD appropriations |

| SENATE | |

| Committee | Jurisdiction |

| Committee on the Budget | Congressional Budget Resolution |

| Committee on Appropriations | All appropriations |

| THUD Subcommittee | THUD appropriations |

Congressional budget resolution. In the spring, Congress formulates its own view of the Federal budget, using the President’s budget request as input. The first major Congressional action is development of a Congressional budget resolution. Once approved, this resolution guides all congressional action when developing legislation for the next year. It sets high-level spending and tax levels, and explicitly sets a deficit or surplus level for the year. However, it does not set Department-level budgets—a task reserved for the follow-on appropriations bills.

After holding hearings on the President’s Budget request, the House and Senate Budget Committees each develop and debate a budget resolution. The resolution moves through the committee, then to the floor of the full chamber. As with an authorization bill, a budget resolution must be passed in identical form by both the House and the Senate. Therefore, the two bodies must resolve differences between House- and Senate-approved budget resolutions via either an exchange of amendments or a conference committee.

Budget resolutions are not law; they simply govern subsequent Congressional appropriations activity. Consequently, they do not require the President’s signature.

Appropriations legislation. After passing a budget resolution, the House and Senate develop appropriations bills. The Constitution requires the House (rather than the Senate) to originate “revenue bills,” which has long been interpreted as including appropriations bills. Accordingly, the House traditionally debates and passes its appropriations bills prior to the Senate, and when debating appropriations bills on the Senate floor, the Senate adopts the bill number (e.g., H.R. 1234) belonging to the corresponding House bill. As a practical matter, though, the Senate may begin informal development of its own bills in parallel to the House process.

To keep total spending consistent with the budget resolution, the Chairs of the House and Senate Appropriations Committees allocate that resolution’s top-line spending numbers among its various subcommittees. Each subcommittee drafts and debates a bill that sets the funding amounts for the programs under its jurisdiction. If approved by the subcommittee, the bill moves on to the full committee. The full committee then debates the bill, and if it approves it, “reports it out” to the full chamber of its respective body of Congress. And as with authorization bills, the appropriations committee typically produces a report to accompany its bill, providing additional direction to the executive branch on how to implement the law once enacted.

Each chamber debates and passes its series of twelve appropriations bills: the THUD bill, plus the eleven others. The House and Senate again resolve their differences via amendment exchange or a conference committee. Once both chambers have approved identical versions of the THUD bill, the legislation goes to the President for signature.

As with any other bill, the President may sign it into law or veto. If the President vetoes the bill, Congress has the ability to override the veto through a 2/3 vote in each chamber.

In addition to the “regular” annual THUD Appropriations Act, three other types of appropriations actions may affect the funding available for the FAHP: a supplemental appropriations act, an omnibus appropriations act, and a continuing resolution (CR).

Supplemental appropriations act. A supplemental appropriations act is sometimes necessary during the course of a fiscal year when it becomes apparent that key operations of the Federal government require funding beyond that provided through the regular appropriations process. When it foresees this situation, the Administration will request that Congress enact supplemental legislation. The Emergency Relief program is, by far, the most common program relating to highways for which Congress has enacted supplemental appropriations.

Omnibus appropriations act. In recent decades Congress has usually been unsuccessful in enacting the entire series of 12 appropriations bills by the beginning of the fiscal year. When unable to pass each individual measure, Congress may at times combine many—or even all—of the bills into a single, consolidated package known as an omnibus. The appropriations process has ended in an omnibus appropriations act in eight of the last ten fiscal years.

An omnibus raises different political dynamics than an individual appropriations bill, as it in effect presents each Member of Congress with a single vote that will either fund or shut down the majority of the Federal government.

Continuing resolution. In the absence of either a regular appropriations act or omnibus, Congress may instead pass a CR. A CR typically extends the previous fiscal year’s legal authorities for a limited period of time (days, weeks, or months). During that period, the CR usually provides pro-rated funding, most commonly based on the prior year’s funding levels.

For the Federal highway program, the continuing resolution provides the obligation limitation for the CR period. It also provides liquidating cash, which allows FHWA to liquidate State obligations (pay States) for projects that are underway.