This chapter presents the activities to undertake in the pre-procurement phase. Table 6 provides a summary of key goals of this phase and successful practices to help achieve them.

| Pre-Procurement Phase Goals | Key Activities |

|---|---|

| Structure a procurement team to provide overall project management |

|

| Establish a project delivery strategy |

|

| Set the stage for stakeholder engagement and required approvals |

|

Each P3 project is unique in terms of the project scope and the expertise it requires throughout the procurement process. In some cases, P3s are procured by an independent office and in others the agency runs the procurement with existing staff resources. In some States, the agency is responsible for the procurement but is subject to approvals and/or oversight by a separate agency or governing body. In all cases the agency's pre-procurement activities should include establishing a framework for involving leadership and decision-makers in the procurement process.

Colorado's High-Performance Transportation Enterprise (HPTE) is an example of a government-owned business established especially for the purpose of pursuing infrastructure projects as P3 procurements. The Commonwealth of Virginia previously established a separate P3 office with dedicated staff, which is now an integral part of the VDOT organization. The organizational structure of the P3 office can define the channels for leadership and decision-maker involvement. Regardless of whether a separate P3 office exists, if an agency is preparing to procure a P3 project, it will need to identify the appropriate number of personnel that will be dedicated to the procurement and delivery of the project. P3 procurements likely will require much of the available time of at least one full time staff person in a leadership role to oversee the process from beginning to end and likely will require significant amounts of time from other support staff with specific expertise in disciplines important to the project.

A P3 procurement requires participation, support, and agreement where applicable from agency senior managers, and a number of governing and legislative entities. In some cases, State legislation requires agencies using P3s to report to the legislature or to obtain legislative support and in some cases, approval of projects. The agency should also coordinate with State, regional, and local jurisdictions and the Federal Government. While interagency agreements may be necessary to address project-specific issues, the process of engaging leadership and decision-maker involvement can be established in advance. This could be articulated in the form of a mission or vision statement of the specialized P3 office, if one exists, or laid out in the form of jurisdiction-wide guidelines, issued pre-procurement, specifying decision-making authority and roles of leadership at different stages of the P3 procurement process.

It is important to note that the teams representing the various leadership roles for the procurement are not mutually exclusive. The P3 procurement management team can and often does include members from key leadership positions within various entities that bear the ultimate responsibility for the project, such as the transportation agency, the P3 office, or specialized P3 entity, if one exists.

The importance of involving leadership in the process does not eliminate the need to delegate decision-making authority to the P3 procurement team that is responsible for the day-to-day direction of the procurement process. Throughout the procurement process, a number of important decisions may need to be made relatively quickly; in many ways, these decisions are precedent-setting to the agency and may also apply to other governmental entities in the same State, and thus the agency should establish appropriate approval processes within its hierarchy to ensure efficient decision-making. Most recent P3 procurements point to the need for both greater flexibility and innovation on the part of the agency along with the ability to be responsive to both the opportunities and challenges that come with the involvement of a private entity in the development of a complex project. Well-defined guidelines for reporting to, and otherwise involving leadership, can help ensure that key decision-makers are kept informed of developments without compromising the agility and decision-making authority of the P3 procurement team. The guidelines also need to be flexible so that they can accommodate unanticipated situations, which are common in P3 procurements.

The procurement of a major project as a P3 requires specialized skills and expertise in addition to those needed for a more standard procurement. These skills are typically provided by a combination of in-house staff and consultant resources. In general, the following skills are a critical part of all P3 procurements.

Colorado High Performance Transportation Enterprise (HPTE) P3 Management Manual

In identifying the P3 Project Team members, the HPTE Director, in coordination with the applicable Region Director, will consider the following key elements:

Colorado HPTE P3 Management Manual

Requires project management to maintain costs and schedule for each phase for both a traditional project delivery approach and the P3 approach. Cost management per the manual also involves assumed risk allocation for major elements of the proposed P3 project and the cost/cost savings and schedule/schedule savings for each project delivery approach and for the development of the initial risk matrix.

In addition to subject matter expertise, the procurement team must recognize the importance of flexibility and the ability to innovate - including willingness to consider creative solutions provided by the private sector and the experience to be able to make sound decisions in the best interest of the public in the face of ever-changing information. Prior experience with P3 projects and procurements is highly desirable to avoid inefficiencies and delays in the overall management of the procurement process.

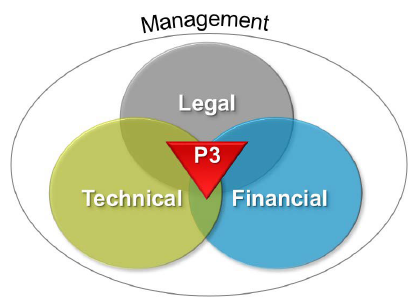

The technical, financial and legal teams work together to bring the three core elements of the procurement into a cohesive whole through the project development phases (see Figure 2 on the next page). However, the perspectives and recommendations of the team members can diverge on occasion, and the agency's decision-makers may have to base their decisions on recommendations from different points of view that may not always agree. For instance, an action in the proposal development phase, such as ROW acquisition can be performed in whole or in part by agency staff and consultants or transferred to the concessionaire. While the legal and technical teams may recommend transferring the risk to the private entity, the financial team would be in the best position to assess the financial implications and feasibility of the risk transfer. The agency's management team would have to decide which recommendation to adopt.

The technical, financial, and legal teams normally include both agency staff and advisors, with at least one public employee in a leadership or coordination role within each team. The ultimate responsibility for managing the project rests with the agency. The P3 Management Manual for the High-Performance Transportation Enterprise (the "HPTE Manual") 22 provides information regarding the management structure of that organization, which may be useful to an agency seeking to use P3s for the first time. The HTPE Manual contemplates having a management team comprised largely (if not solely) of agency staff members with support as needed from specialized advisors. Since the agency bears the ultimate responsibility for the project, it is good practice for agency staff to be actively involved in the day-to-day process of the procurement.

In addition to coordination between the technical, legal, and financial teams, the management team can also serve as the "face" of the procurement team, interfacing with administrative leadership and other stakeholders and involving leadership on significant decisions as the procurement progresses.

Project management is a critical and complex function in the procurement of a project as a P3. In comparison to a traditional procurement, a P3 project typically involves more stakeholders, greater complexity of project tasks, a larger team including both specialized advisors and internal staff, and a higher degree of vulnerability to external and internal factors that could impact the procurement schedule. Furthermore, most P3 projects, especially the first such procurement for an agency, typically attract a higher level of interest and scrutiny from the public, media, and elected officials, requiring seasoned management of the procurement process. It is therefore essential for the agency to have an experienced project manager. While it would be preferable for the project manager to have experience with P3 project development and procurement, it is possible that the agency may not have access to such expertise, in which case a project manager with design-build procurement experience becomes essential.

The following are some of the key aspects of the project manager/management team's responsibilities:

Schedule Management: The project manager (or management team) develops and manages the schedule throughout the procurement process. The schedule should identify the procurement phases and activities involved in each phase, their timeline and dependencies, key decisions points and activities on the critical path. Schedule management also involves risk identification and management of activities that have the potential to negatively impact the procurement schedule (such as a late decision to pursue TIFIA funding, legislative approvals, political considerations, legal challenges, and others.)

Cost Management: The project management team typically develops and manages costs for each procurement phase. Other key considerations involved in cost management include cost of financing, cost of engaging specialized advisors, conducting a VfM analysis and initial and ongoing analysis of cost of alternative project delivery options as prescribed by guidelines and/or in response to specific project needs. Payment of stipends to unsuccessful bidders is a successful practice and should be included in the cost considerations of a P3 procurement.

Staff and Consultant Management and Engagement: As noted in section 3.1, the P3 procurement team involves a diverse set of expertise and potentially several sub-teams to successfully deliver the project. The project management team is typically responsible for the establishment and ongoing management of the various teams, including activities such as staffing, appointing team leads, delegating tasks, and ensuring coordinated functioning of the teams.

Leadership Engagement: In addition to providing periodic briefing updates on the progress of the P3 development, the project management team also makes decisions regarding the need to "bump-up" key issues to leadership and decision-makers. These may occur at scheduled or unscheduled points during the procurement.

Industry/ Proposer Engagement: This involves an industry forum and one-on-one sessions, communications and negotiations with the proposers through the RFQ and RFP process, determining stipends for unsuccessful bidders, and other activities involved with engagement of proposers through the procurement process.

Training: The success of a P3 procurement will depend in large part on the personnel involved in the procurement process and the expertise and training they have and receive in advance of the procurement. Appropriate training can help educate stakeholders, including agency staff and contractors, in setting procurement expectations, address risk and foster innovation.

Public Outreach: As with some of the other project management tasks, this may be delegated to a specialized group within the P3 project team. However, the project management team may be ultimately responsible for education of the public and elected officials on the P3 approach, conducting workshops and public hearings, meeting with elected officials and other stakeholders, and conducting other outreach to the public and media.

For the Purple Line procurement, Maryland DOT (MDOT) and Maryland Transit Administration (MTA) established a leadership team during the development of the RFP specifically to provide oversight on the risk allocation decisions and provide guidance on how issues should be addressed. This team included agency leadership from MDOT and MTA along with financial and technical advisors. As this was the first P3 project for both agencies, there was no formal process to budget for consultant costs. The final costs for engaging advisors were significantly higher than initial estimates.

Successful Practice

Advisors engaged to support a P3 procurement should have prior experience advising P3 deals. Advisors with only traditional procurement experience are not likely to be sufficiently qualified to support a P3 procurement.

State law may designate a specific public entity to engage specialized legal or financial and investment advisors to help guide the State's legal and investment decisions or may permit individual agencies to engage such advisors. The entity thus empowered may hire specialized consultants for specific programs or on an on-call basis. Although some agencies have indicated an interest in procuring a single contract to obtain technical, financial, and legal expertise within a single team of advisors, experts generally recommend separate procurements for each area of specialty. By procuring each service separately, the agency retains the ability to obtain the best consultant in each sub-area. Furthermore, with respect to legal services, agencies should consider whether a sub-consultant arrangement might create a barrier to attorney-client communications or affect the agency's ability to rely on the attorney-client privilege.

Organizations that have procured multiple P3 contracts often maintain a bench of consultants with agreed-upon rates that can be engaged on a task order basis as needed through the procurement. Such an arrangement enables agency staff to participate heavily in the upfront tasks and engage consultants on an as-needed basis as the procurement proceeds. The consultants can be called upon to augment the P3 office staff as needed for each P3 project procurement. The VDOT P3 Office follows this strategy. States such as Florida and Texas, which have had a pipeline of P3 procurements and several P3 projects proceeding simultaneously, typically maintain a pool of consultants with a variety of specialized expertise who are engaged based on the type of expertise required for a specific procurement. An "on-call" or "bench" model for consultant engagement is suitable for agencies that have significant in-house expertise with the P3 procurement process. An agency with little to no prior experience with P3 project delivery could gain by early and more well-defined engagement of seasoned consultants or commercial advisors or by acquiring expertise through strategic hiring.

The level of engagement of expert advisors depends both upon the staff capacity of the agency as well as the volume of P3 procurements that the agency delivers annually. A number of agencies with experience in P3 procurements have noted that specialized consultants can be expensive and that their involvement needs to be actively managed. Having a very well-defined scope for expert advisors and a solid in-house management and monitoring process can ensure that the advisors are well managed and cost-effective, reducing the risk that the agency may spend money on activities that become redundant as the procurement proceeds.

In managing external advisors, agencies should consider how best to:

External advisor support is typically a significant portion of the predevelopment budget. As such, the scope, budget, and schedule for the advisors/consultants should be well-managed with knowledgeable and dedicated staff.

The HPTE Manual directs the HPTE Director to identify the following for advisory services contracts:

The P3 Project Manager is required to coordinate the expert advisors' efforts throughout the project development phase.

Confidentiality

P3 procurements involve the need to balance the public interest in having an open and transparent process against the public interest in holding a fair and open competition for the P3 contract. Private sector participants in P3 procurements are highly concerned about the possibility that their proprietary ideas may be disclosed to competitors over the course of the procurement process, and often prefer to avoid public disclosure of their concepts even after the contract is awarded.

Many agencies have adopted policies requiring all agency staff and consultants that have, or will have access to confidential data, to execute a non-disclosure agreement during the pre-procurement phase that will remain in effect throughout the procurement and thereafter.

As discussed in sections 4.2 and 8.3, the public interest in transparency regarding procurements has resulted in a significant level of disclosure, often by posting information on project websites. The final RFQ and RFP, and any addenda, are normally posted after issuance. Some information regarding proposals may be posted shortly after receipt of proposals, but the proposals themselves typically are not posted. The final contract documents are usually posted in their entirety.

Organizational Conflicts of Interest

Federally funded contracts are subject to rules requiring agencies to take appropriate measures to avoid organizational conflicts of interest (OCI). For example, 23 CFR 1.33 provides that no person performing services for a State or government instrumentality in connection with a project shall have directly or indirectly a financial or other personal interest other than employment in any contract or subcontract in connection with such project. Additionally, 2 CFR 200.317 and 2 CFR 1201.317 provide that States and subrecipients of States, respectively, follow the same policies and procedures used, or authorized to be used by a State, as would be applied for procurements with non-Federal funds. Most States have developed internal conflicts of interest procedures that must be adhered to under the above government-wide uniform requirements. FTA's Best Practices Procurement Manual (BPPM) 23 includes an extensive discussion regarding OCI issues, 24 which are specific to FTA-related financial assistance (but include TIFIA credit assistance for transit projects); and FHWA's Design-Build Rule includes specific OCI requirements, 25 which are specific to FHWA Federal-aid highway funding (including TIFIA credit assistance for highway projects). Agencies must also comply with any OCI requirements imposed by their own State law.

For example, the FHWA rule on Federal-aid highway funded design-build projects defines OCI as follows:

Organizational conflict of interest means that because of other activities or relationships with other persons, a person is unable or potentially unable to render impartial assistance or advice to the owner, or the person's objectivity in performing the contract work is or might be otherwise impaired, or a person has an unfair competitive advantage. 26

Situations raising potential OCI issues include:

If a procurement is affected by a potential OCI, it may be possible to adopt mitigation measures to avoid the conflict. However, if the OCI is not identified early, a problem may arise that cannot be cured, and in some cases the validity of the procurement may be affected, requiring the entire procurement to be re-done. As a result, it is vital that agencies consider how to deal with OCI issues as early in the procurement process as reasonably possible. Measures that agencies can take during the pre-procurement phase include:

The agency should consider the advantages and disadvantages of allowing consultants to participate on P3 teams despite their prior involvement in various aspects of the project. If all advisors involved in the planning and initial design process are precluded from joining P3 teams, that will reduce the pool of qualified firms eligible to submit proposals. The OCI policy should provide guidance regarding how different types of assignments will be treated and means of mitigating potential conflicts.

Refer to sections 4.3 and 4.4 for a discussion of additional OCI issues that should be addressed in putting the procurement package together and in evaluating statements of qualifications (SOQ) and proposals.

A project's success is dependent upon the implementation of an effective project delivery strategy. The delivery strategy will impact, among other things, project cost, quality of design, construction, long-term maintenance, and the schedule for completion of construction. Agencies planning large projects can improve their chances of success by performing a thorough assessment of the key objectives for the project and the delivery strategies available to it. Not all projects are appropriate for P3 delivery. The most appropriate delivery strategy will depend on the project owner's objectives as well as the specific project characteristics and circumstances (including project scope, corridor tolling, cost estimates, funding sources, traffic, ridership and revenues). This section discusses certain steps to be followed to assess whether a project is suitable for P3, as well as measures that can be implemented to ensure that the procurement will be successful.

Generally, the following project characteristics indicate that it may be appropriate for an agency to consider P3 delivery for a particular project:

In determining suitability, the agency should be mindful of the ability of the project to attract financing and equity investor interest.

Successful Practice

Following the initial screening, the agency should proceed with a business case analysis for those projects, analyzing the project scope, size, and complexity to determine whether a public private partnership can deliver the best value to the traveling public. Additional information regarding the screening process and development of a business case can be found on FHWA's website.

See the "P3 SCREEN Analytical Tool" web page, which is part of FHWA's P3 Toolkit, available at: https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ipd/p3/toolkit/analytical_tools

/p3_screen/.

See also the 2016 Peer Exchange report for the "P3 Peer Exchange: San Francisco Bay Area, California" at https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ipd/p3/p3_training/peer_ex_san_fran

_mar2016/.

In some cases, it may be readily apparent that P3 delivery is not appropriate for a particular project despite the existence of some of the above characteristics; in other cases, the agency should conduct an initial screening to assess which projects in the agency's capital program may be appropriate for P3 delivery (that is, where P3 delivery likely offers best value for limited public funds). For major projects, Federal law requires the agency to assess in its financial plan whether a P3 would be appropriate to deliver the project. 28

The business case study typically includes a VfM analysis comparing ways to deliver a project to determine which project delivery approach is most likely to meet the requirements and objectives for the lowest cost over the project's life. The business case analysis helps the agency determine the most suitable delivery method and can also be used as a tool in seeking political support and stakeholder consensus.

Highway and transit project sponsors receiving Federal assistance are required to conduct a VfM analysis in certain circumstances. Federal law requires the procuring agency of a P3 project seeking a loan or credit assistance under TIFIA or RRIF, a PAB allocation, or a grant under the INFRA program to conduct a "value for money analysis or a comparable analysis prior to deciding to advance the project as a public-private partnership." 29 Furthermore, the U.S. DOT, on request, may provide "technical assistance [to an agency delivering a Title 23 project] ... in analyzing whether the use of a public-private partnership agreement would provide value compared to traditional public delivery methods." 30 For public transportation projects governed by Title 49, the U.S. Code requires the U.S. DOT to "encourage sponsors to conduct assessments to determine whether use of a public-private partnership represents a better public and financial benefit than a similar transaction using public funding or public project delivery." 31 The Build America Bureau has responsibility for developing and monitoring best practices, of which this guide is a part, to help public agencies considering and developing P3 projects. In addition, FHWA has delivered workshops on key areas of P3 project development at different stages of the P3 process to assist public agencies as they consider, develop, procure and implement P3 projects.

VfM analyses typically rely on a "public sector comparator" and either a "shadow bid" or actual bid that enables the agency to assess the pros and cons of a range of traditional and P3 delivery methods. The public-sector comparator is a project life-cycle estimate of the cost of traditional project delivery using a DBB or DB method, including the costs of agency-delivered operations and maintenance. A shadow bid provides a similar project life-cycle cost estimate for the alternative delivery method. In addition to project costs, the analysis considers costs of financing and the allocation of project risks between the agency and the concessionaire, and assesses the effect of different delivery methods on exposure to such risks. It also may take into account differences in procurement and oversight costs, Federal financing subsidies, and/or the taxes that would be paid by private entities but not by a public agency. The goal is to undertake an "apples to apples" comparison to the maximum extent possible to help the agency evaluate the project delivery approach for the project under consideration. The analysis is complex and is typically provided by a team that includes financial, technical, and legal advisors with expertise in traditional and P3 project delivery.

The FHWA P3-VALUE Toolkit includes a guidebook concerning VfM assessments. 32 The Toolkit also includes the Public-Private Partnership Value for Money Analysis to Learn and Understand Evaluation tool (P3-VALUE 2.1) and other resources. 33

The agency should clearly articulate the policy goals of the project as these will inform the development of procurement specifics such as scope, terms, and risk allocation as well as the subsequent evaluation and selection decisions, and will be relevant in administering the procurement. At various stages of the procurement, these goals should be reviewed to confirm that the project is proceeding in the right direction. Most agencies set out their project goals in the procurement documents to ensure the proposers understand the agency's goals and will submit proposals that support achievement of these goals.

One of the major benefits to P3 project delivery is that it offers significant opportunities for innovation by allowing the private sector flexibility to develop efficient methods to meet project goals combined with incentives that align the concessionaire's interests with the public interest. 34 In structuring the procurement and developing contract documents, the agency should make sure that opportunities for innovation are offered at appropriate points in the process. This includes:

Once the agency decides to use a P3 approach to develop a specific project, it will need to determine the scope of the concession, including defining the project, determining the respective roles and responsibilities of the agency and concessionaire, deciding whether the concession will include a lease or other form of property interest, and setting the term of the concession. As discussed in the Second Strategic Highway Research Program (SHRP2) report entitled "Effect of Public-Private Partnerships and Nontraditional Procurement Processes on Highway Planning, Environmental Review, and Collaborative Decision Making," 35 these decisions must be coordinated with the environmental review process for the project. Technical, financial, legal, and political considerations should be factored into the decision, along with the agency's goals relating to the project. Furthermore, the VfM is typically built based on assumptions regarding scope, and it may be necessary to revisit the VfM if the final decision differs from those assumptions.

As part of this analysis, the agency should consider the extent of an asset's useful life and determine the point in an asset's lifecycle where significant capital renewal might be required. It may not be cost effective to require the concessionaire to price major renewal work or to replace critical equipment towards the end of the project term because of the cost uncertainty and difficulty of pricing major works 30 to 50 years into the future. It might prove more efficient for the public sector to procure the work as part of a separate contract when the P3 term is complete or seek to replace the asset as part of a new procurement at or near the end of the asset's useful life. Agencies also should evaluate how to most effectively use warranty periods to ensure the performance of equipment and technology.

The agency's initial determinations regarding the scope of a concession require assessment of technical considerations, such as logical project boundaries, costs of acquiring rights of way, interfaces with other facilities, and major risks affecting design, construction, operation and maintenance of the project. These initial determinations will form the basis for the high-level financial assessment discussed below. For projects in colder areas, one issue to be considered is whether snow and ice management should be included in, or excluded from, the scope. Although it is preferable to make this decision early in the procurement process, since it is relevant to proposers in forming their teams, agencies may opt to defer this decision until later in the procurement process, as the answer may change depending on factors not yet known when the initial P3 decision is made.

For revenue-financed projects, such as Virginia's I-495 Capital Beltway HOT Lanes project described in Appendix B, traffic and revenue studies for different configurations, as well as projected costs of project development, are critical factors in establishing the project scope. For projects that primarily rely on public funding, such as the Purple Line availability payment project described in Appendix B, determining the availability and timing of the grant and other public funds that will support the availability payments over the project's life takes the place of revenue projections in the analysis. In all cases, the term of the concession must be long enough to allow projected revenues and/or availability payments to fund repayment of debt plus a reasonable return on capital.

Legal issues to be considered in the process of setting scope and term include any constraints that may apply to concessions under applicable law. For example, if the agency's enabling legislation only permits concessions for projects that can self-fund operations, it will need to be factored into the scope. In many cases, the concession term will be subject to statutory or constitutional limitations. As an example, the statute that authorized the Purple Line concession states that a P3 agreement may not exceed 50 years, including all renewals and extensions, unless an exception applies.

Public policy considerations are crucial to decisions regarding project scope. It is important to ensure that the project has the reliable support of stakeholders, including local and State-level leadership and the general public. In setting the scope of the project, the agency should consider whether adding or removing different elements from the scope will affect political support for the project.

If the agency is using a pre-development agreement (PDA) approach, discussed in section 3.5, the scope of the project-as well as the term-will be informed by the feasibility analysis studies undertaken by the concessionaire during the initial phase and the environmental review process. Appendix B describes the process followed for the North Tarrant Express project.

Successful P3 project delivery is dependent on efficient and effective risk assessment and allocation. To be most effective, risk assessment should begin well before a project delivery method is chosen to enable a more accurate business case analysis and provide the agency with the ability to determine and optimize project delivery alternatives. Proper risk assessment also will assist the agency with structuring the P3 contract because it allows the agency to optimize risk allocation by ensuring that the risks are transferred to (or retained by) the party in the best position to handle them. The FHWA "Guidebook for Risk Assessment in Public Private Partnerships" describes in detail how an agency can utilize risk management to ensure the successful delivery of a P3 project. 36

Section 2.2 described certain issues to be considered by an agency in its threshold legal analysis relating to use of P3s. Further legal analysis is needed once the agency has made the decision to proceed with a P3 procurement and is in a pre-procurement mode. In addition to revisiting the legal issues identified in section 2.2, the agency should consider how the procurement and contract will be affected by:

In order to ensure that applicable legal requirements are identified, the legal team should review the agency's standard contract and procurement documents to identify standard provisions that may need to be added to the documents.

It may be useful to develop checklists identifying applicable local, State, and Federal requirements so as to facilitate a compliance review as the procurement package is being developed. 42

As noted in section 3.1, the internal communications strategy between the P3 procurement sub-teams and between the procurement team and leadership should be identified in advance of procurement and should involve flexibility to allow for decision-making by the P3 procurement management team. The guidelines for internal communication with agency leadership can be outlined in P3 guidance documentation and normally include:

Aside from periodic updates, it may be important to involve leadership at critical unscheduled decision-points and when important issues or risks arise. These determinations may be made by project leadership in consultation with project staff.

The agency also should develop a strategy for communications with stakeholders, the media, and the public, including initial agency outreach as discussed in section 3.1 and outreach efforts delegated to the concessionaire.

As discussed in section 4.4.5, the agency also should establish rules applicable to communications with proposers.

Prior to issuance of an RFQ, and at various stages thereafter prior to submission of proposals, the agency may wish to hold meetings to solicit private sector input into the proposed approach to delivering the proposed project and/or more specific comments regarding the draft RFQ documents, as well as any other available draft documents relevant to the project and the overall procurement process and schedule.

A market sounding may be informal, such as the exercise conducted by the Indiana Finance Authority in 2010 for the Ohio River Bridges Project or another recent process involving a series of 1-hour calls with a cross-section of industry participants with a specific list of questions seeking industry feedback.

The agency may also conduct a more formal sounding, which could include:

The following discussion concerns post-procurement activities as well as issues directly affecting a P3 procurement, as the agency must have a full understanding of the issues in order to make appropriate decisions regarding how to proceed with a P3 procurement. Much of this discussion and additional discussion regarding the relationships between P3 project development and the environmental review process can be found in a report prepared for the Second Strategic Highway Research Program entitled "Effect of Public-Private Partnerships and Nontraditional Procurement Processes on Highway Planning, Environmental Review and Collaborative Decision Making." 44

To appropriately address the issues raised by the environmental review process for projects proposed for funding under title 23 U.S.C. and title 49 U.S.C. Chapter 53, it is necessary to begin with the transportation planning process required by Federal law. 45 The statewide transportation improvement program (STIP) and the metropolitan planning organization (MPO) transportation improvement program (TIP) must include capital and non-capital surface transportation projects within the boundaries of the State proposed for funding under title 23 U.S.C. and title 49 U.S.C. Chapter 53 (23 CFR 450.218(g) and 450.326(e)). The project must also be consistent with the long-range statewide transportation plan and, if it is in a metropolitan planning area, the metropolitan transportation plan (MTP) (23 CFR 450.218(k) and 450.326(i)). Urbanized areas with populations of more than 50,000 individuals must have an MPO to carry out the transportation planning process. That metropolitan planning process results in an MTP that covers a planning horizon of at least 20 years, and a TIP, which sets forth the projects which are to be implemented over the next four years. 46 The STIP MTP, and TIP must be "fiscally constrained." That means that the funding for a project is identified in the MTP and STIP/TIP and is reasonably expected to be available within the time period contemplated for completion of the project (23 CFR 450.218(o), 23 CFR 450.326(k)), 23 CFR 450.324(f)(11). For P3 projects, this also means that the State or other project sponsor has or is likely to obtain the legal authority to carry out a P3 project. Private investment and any needed public subsidy will need to be reasonably expected to be available at the time the project is included in the STIP/TIP for the time-period when the project is implemented. The FHWA and FTA will jointly look at whether the current cost estimate remains consistent with the MTP, STIP and TIP, and the level of commitment of potential private investors. 47

In nonattainment areas and maintenance areas, 48 funding for projects proposed for the first two years of the STIP/TIP must be "available" or "committed." (23 CFR 450.218(m) and 450.326(k)). 49

The NEPA process and compliance with other environmental requirements for P3 projects is the same as for non-P3 projects. Once the project sponsor (State or local agency) identifies a project to implement, it contacts its regional U.S. DOT modal office (e.g., the FHWA Division Office or FTA Regional Office) to begin the environmental review process required by NEPA. 50 Additionally, highway, transit, and rail projects are covered by a DOT-specific environmental review process under 23 CFR 771/774 and 23 U.S.C. § 139. Typically, the project sponsor, such as the State department of transportation (DOT) for highway projects or a local transit agency for transit projects, conducts early studies to identify the general environmental conditions, potential socio-economic issues, and other considerations. This information and the scope of the project assist the agency in determining the appropriate NEPA class of action, either a categorical exclusion, environmental assessment (EA), or environmental impact statement (EIS). FHWA, FRA, and FTA's joint NEPA implementing regulations provide lists of CEs, which allow simplified review of projects that neither individually or cumulatively have a significant effect on the quality of the human environment. 51 An EA is prepared for projects that are not categorically excluded but may not require an EIS. If the EA demonstrates no significant impact the process is concluded with a finding of no significant impact (FONSI). If, at any point in the EA process, the agency determines that the action is likely to have a significant impact on the environment, the preparation of an EIS is required. (23 CFR 771.119(i)).

When a project requires an EIS, a Notice of Intent (NOI) to prepare an EIS is published in the Federal Register to notify the public of the general nature of the proposed project and solicit public input on the scope of the project and the significant issues for further study in the EIS. For highway and transit projects, the transportation planning process should be the primary source for identifying the project purpose and need and potential project alternatives.

The draft EIS (DEIS) is the next formal step. The DEIS must evaluate all reasonable alternatives to the action and discuss the reasons why other alternatives, which may have been considered, were eliminated from detailed study. The DEIS must also summarize the studies, reviews, consultations, and coordination required by environmental laws or Executive Orders to the extent appropriate at this stage in the environmental process (23 CFR 771.123(c)). Public involvement must be included as a part of the DEIS as prescribed under 23 CFR 771.111(h) for highway projects and under 23 CFR 771.111(i) for transit projects. The agency coordinates and requests comments from other affected agencies and the public (including resource agencies). All public comments and comments from interested stakeholders should be addressed in the final EIS (FEIS). This includes comments on both the natural and human environment, and comments as they relate to consideration of alternatives and selection of the preferred alternative. When all of these comments are considered and (usually) disagreements with resource agencies are resolved, the lead agencies to the maximum extent practicable will issue a single document (combined FEIS/record of decision (ROD)) pursuant to 23 U.S.C. 139(n), or will issue the FEIS. The FEIS responds to all substantive comments received, may include project changes that may have occurred in response to comments or other considerations, etc. The ROD provides the agency decision and may be issued no sooner than 30 days after completion of the FEIS if a single document (combined FEIS/ROD) is not used. The single document (combined FEIS/ROD) will contain the same type of information found in separately issued FEISs and RODs. Once the single document (combined FEIS/ROD) or ROD is issued, highway projects may be approved for the next phase of project development, typically final design and right-of-way acquisition. For transit projects, after the combined FEIS/ROD or ROD is issued FTA may issue a Letter of No Prejudice 52 or the FFGA, if appropriate, and project can proceed to final design.

The EIS also documents agency compliance with a myriad of other Federal laws that apply to a Federal transportation project. These may include but are not limited to: Section 404 of the Clean Water Act (relating to the dredging and filling of Waters of the United States); Section 4(f) requirements (relating to the preservation of historic sites and publicly owned parks); 53 Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act; Section 7 of the Endangered Species Act; and many others. Most of the requirements are resolved at approximately the same time as the issuance of the ROD. If full compliance is not possible by the time of the final EIS, the final EIS should reflect consultation with the appropriate agencies and provide reasonable assurance that the requirements will be met. 54 However, if a specific permit is required, it is often left to the concessionaire to obtain such permits. The FEIS must include any necessary required mitigation measures, which will be enforced as part of the conditions for FHWA/FTA approval (23 CFR 771.125(a)(1)).

The concerns that are specific to P3 projects and strategies for dealing with them are discussed in the following sections.

Potential concessionaires and their lenders are highly interested in the timeline for obtaining NEPA approvals for potential P3 projects, particularly if the project will require an EIS, due to the uncertainties associated with the process until the ROD is issued. Until the process is complete, it remains unknown which alternative will be adopted, or if the project should be built at all. The private investor may have to forego other opportunities during this period, and the period of uncertainty regarding the project could be extended even further if there is litigation. As a result, proposers may be reluctant to participate in a procurement for a project that is in the early stages of the NEPA analysis. 55

FHWA has provided information regarding the amount of time it takes to complete the EIS process from the NOI to issuance of the ROD. The time has declined between 2011 and today. Thus, in 2011 the median time to complete an EIS was 79 months, while in recent years, this number has hovered around 45 months. The numbers for FTA are not readily available. 56

In considering the time it takes to complete the NEPA process, the following factors should be considered:

On August 15, 2017, President Trump issued Executive Order 13807 (E.O. 13807), which encourages agencies to reduce the average time needed to complete the EIS process to approximately two years and establishes the One Federal Decision policy. 57 FHWA has worked with the U.S. Coast Guard, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the National Marine Fisheries Services to develop a Written Agreement, committing to work together to achieve the E.O. 13807 goals. 58

The NEPA process is designed to inform the public and decision-makers of the environmental and related consequences of a particular Federal action. A private party with a stake in the outcome of the NEPA process may not prepare an EIS; however, a third-party contracting mechanism may be used. However, for PDA concessions, the agency may ask the concessionaire to provide studies that will inform the NEPA process. This can be very useful because the expertise of the concessionaire's team and any innovative plans the concessionaire may have for the project can be incorporated into the project.

FHWA's Design-Build Rule specifically permits award of P3 agreements prior to completion of the NEPA process (subject to conditions), but prohibits performance of final design and most other project activities until after completion of the NEPA process. 59 A number of agencies have entered into "pre-development agreements" (PDAs) 60 with concessionaires to obtain the benefit of early involvement by the private sector. The use of pre-development or comprehensive development agreements are generally a function of State law and State policy. These agencies should consult with agency counsel for consistency with State and local procurement procedures. However, as noted above, the concessionaire likely will price the risk of timely completion of the NEPA process into the concession agreement due to the complexities involved in NEPA analysis and the time required to complete the analysis for a large, complex project.

Another feature of P3 RFPs is the ability to propose ATCs that can save cost and improve project function. These ATCs, if too different from the project described in the RFP, can also lead to additional NEPA work. This issue is discussed further below.

If tolling is planned or being considered, it should be documented in the NEPA document and its potential impacts analyzed.

Transit projects will likely have user fees in the form of fares rather than tolls, and use of a P3 approach for a transit project might result in a higher fare or require a public subsidy. Consequently, transit projects may require an analysis comparable to that undertaken for toll projects.

For both highway and transit projects, private sector involvement in transportation facilities can be controversial. Future difficulties may be averted if the agency makes it apparent early on that a project is being considered for implementation through a P3 delivery approach, and the reasons for consideration of P3 delivery.

Should the agency decide to pursue a P3 RFP for the construction or modification of a transportation facility following the NEPA process, the selected proposer would be subject to constraints based on the final NEPA documents. In most EISs, completion of the ROD is considered acceptance of the general project location and concepts described in the environmental review documents unless otherwise specified by the approving official. 63 The project is generally described in broad terms, giving the winning proposer considerable flexibility in the design of a new facility. Any changes post-NEPA may be subject to additional analyses 64 and re-evaluation. In urban areas where the project is to be built in a very confined area, the level of design needed in the EIS can be much greater than is typical for more rural areas, resulting in less flexibility for a potential P3 partner.

The NEPA process and requirements in related statutes 65 often result in specific mitigation measures that become conditions to the approval(s) of the project. Mitigation may include costly features that require constant maintenance to be effective. For example, a newly created wetland may require considerable care until it becomes self-sustaining. Thus, the addition of costly and difficult mitigation measures can make a project less attractive to private investors.

The ability of a Federal agency to participate in mitigation measures or project changes is governed by law. An agency must have a legal basis for all expenditures it makes. Thus, while a range of mitigation measures are considered legitimate project expenses, unrelated betterments could not be approved without additional legal authority. Once an agency identifies such legal authority, that authority would apply generally. There is no such thing as a one-time Federal approval. This policy concern might also limit the kinds of mitigation measures an agency can consider.

Government agencies also may be reluctant to agree to new or novel mitigation measures, especially when the measures are only marginally related to the impacts caused. Indeed, such mitigation measures may be outside of the limits of what the Federal Government can impose on a grantee, and the Federal agency may be precluded by applicable law from implementing such measures or believe that it is not in the agency's interest to fund or otherwise implement them. For example, in order to resolve local concerns on the Central Artery/Tunnel Project in Boston, Massachusetts, the State agreed to provide a wide array of local improvements. Many of these went significantly beyond reducing adverse impacts attributable to the federally funded transportation project. FHWA took care to note that these improvements were not to be treated as mitigation in the EIS because that would have put FHWA in the position of having to ensure their implementation.

Private investors and the public sector have different viewpoints relating to prospective mitigation measures. A concessionaire's primary concerns may be whether the mitigation measures are so expensive as to jeopardize the profitability of the project and whether the delay cost in arguing about a particular mitigation measure is more or less expensive than simply accepting it. These considerations may lead a proposer to incorporate a measure into a project that a government agency could or would not accept. Staying on schedule and avoiding delay may be critical to the success of a P3 project. Delays cost money and extend the time required to open the project for revenue service. Thus, a concessionaire might advocate inclusion of mitigation measures that will resolve a controversy, with the goal of avoiding project delays, without regard to precedent set for future projects. Project sponsors and private investors should clearly identify measures that may expedite the schedule to FHWA/FTA, but recognize that the measures may be excluded from Federal participation.

Typically, P3 agreements require the concessionaire to obtain any necessary permits. This could include permits under Sections 401 (discharge of pollutants, usually during construction) and 404 (dredge and fill) of the Clean Water Act, and many other State and Federal permits. Under current law and practice, these permits require a level of design detail not available at the EIS stage, or they depend on matters within the control of the contractor. There are times when difficulty regarding a particular permit may arise. If the difficulty arises from an issue within the control of the agency, or if it can cause significant delay, it may be in the agency's interest to assist with or intervene in the matter.

The concessionaire typically is under considerable economic pressure to expedite project delivery in order to accelerate the revenue start date. Extensive delays or tardy responses to requests for information or comment can significantly increase the project costs. This is different for a government transportation agency, that may have any number of projects under development at any given time. The dedicated concessionaire project team typically has only one project at issue. The government sponsor of a project should monitor the development and execution of the required permits and be prepared to support the concessionaire in its efforts to obtain necessary permits in a timely manner if an issue arises with which the agency can help.

"Due diligence" is a term commonly used to describe the steps taken by a person seeking to acquire, invest in or lend money to a business, ensuring that the buyer, investor, or lender has reviewed all material information relevant to the transaction. In the case of a P3 project, the agency should conduct its own due diligence process to ensure that all relevant information is considered in making decisions regarding the procurement, as well as to assist equity investors and lenders in deciding whether to invest in the project. The agency should also work to ensure that all documents that should be included in the procurement package are assembled and available for review prior to issuance of the RFP.

Due diligence efforts form the foundation of each of the project activities.

High-level issues relating to defining the scope of the project are discussed in Section 3.2.3. Project definition is also interrelated with the environmental review process discussed in section 3.3 and may be affected by discussions with industry.

Once the high-level decisions are made about the scope of the project, the agency's technical team will need to start (or continue) the process of assembling and drafting documents serving to define the project in sufficient detail to enable potential proposers to make reasonable assessments of project costs and risk allocation and to minimize contingencies. Steps to be taken include review of available data regarding the project area and deciding whether to invest in additional surveys and studies to provide more reliable information to the proposers or to simply provide the existing documents as reference documents. The technical team should establish a process for drafting technical provisions, which typically involves assignment of responsibility for individual sections to staff or advisors with relevant expertise, with a single individual responsible for compiling the specifications into a set of provisions that describe the project scope.

In addition to describing requirements for design, construction, and operations, and maintenance work, the provisions will identify matters such as applicable standards, data and reports, any available preliminary design drawings, service requirements, handback requirements, ROW, utility and access information, and other technical considerations.

Successful Practice

It is essential that the agency consider policies related to tolling (such as rate ceilings, schedule of toll rate increases, and discounts or exceptions) early in the procurement process and communicate its decisions to the private parties. It can be very costly for the agency to adjust tolling policies after financial close is reached and the project is in operation.

Traffic/ridership and revenue projections are at the center of P3 transportation projects that involve financing or payments tied to facility usage and revenue and will play an important role in all project phases. These may be of less importance in the case of non-revenue generating projects or availability payment concessions. The traffic/ridership and revenue study will assess corridor traffic demand, projected ridership, user willingness to pay, toll policy and system requirements, and future growth characteristics, among other factors. The agency's initial traffic/ridership and revenue projections should clearly articulate the methodology for data collection and modeling, major assumptions, and sensitivity testing. The results of such modeling should be provided to potential proposers for information only, and the proposers should be cautioned that they must perform their own studies. Reliance on any information provided by the agency will be at the proposer's own risk. Nonetheless, the strength of the agency's preliminary traffic/ridership and revenue study will likely affect the level of private sector interest in the P3 project.

In developing these projections, agencies should consider various issues that span the operating life-cycle of the facility. For example, for highway toll concessions, agencies should consider toll policy measures such as requirements and possible limitations on toll increases during the contract term and whether to provide special consideration for local or high-volume users.

It also is important to consider the approach to toll operations and maintenance, such as whether the agency will require the concessionaire to be responsible for the operations and maintenance of tolling or to use existing systems for tolling. In the former case, the proposers should assess alternatives available to reduce toll collection risk, and in the latter, they will be concerned about the level of risk associated with the existing systems.

If NEPA approval is not yet obtained, the FHWA Design-Build rule provides that the RFP must identify the current status and state that no commitment will be made to any alternative under evaluation, including the no-build alternative. 66 This practice is consistent with FTA policy. Due diligence efforts of State and local project sponsors will be needed to identify the environmental and other approvals necessary for design and construction of the project and to ensure the required information is included in the RFP, including identifying the approvals that will be obtained by the agency and the anticipated timelines for those approvals. The RFP documents also often include a list of approvals that will be the concessionaire's responsibility.

The potential for delays to P3 projects associated with environmental approvals is perceived as a major risk by the private sector and lenders. It is true that the NEPA process can encounter significant administrative delays relating to procedural issues, and that litigation can result in injunctions causing further, extended delays. If litigation is still a possibility, this can be an area of significant concern to proposers, resulting in higher cost and possible withdrawal of proposers from the procurement, if the agency seeks to transfer environmental risk to the proposers. Even though the majority of cases result in a decision that does not disrupt the project schedule, 67 agencies must consider the risk as perceived by the private sector in deciding how to structure the procurement and allocate risk in the contract.

The risk of unknown conditions at the site is a major issue for P3 projects as the potential cost and delays that may be caused by hidden conditions can be significant. Conditions to consider include:

By definition, unknown conditions are impossible to quantify in advance of final design and construction. Although it may be possible for the agency to transfer these risks to a concessionaire, particularly for revenue risk projects where the concessionaire may be considered the equivalent of the project owner, proposers are highly concerned about the potential for additional costs and delays associated with unforeseeable risks and argue that the public interest is not well-served by a risk allocation approach that requires the private sector to account for that uncertainty by including a significant contingency in the price proposals. Regardless of which party bears the risk of unknown conditions, any action that the agency can take during the pre-proposal period to control this risk will be beneficial to the project. This normally includes conducting geotechnical studies and other surveys in relevant areas. For certain projects, studies regarding the condition of existing facilities may also be advisable.

Issues associated with utility relocations are another major risk for P3 documents. As many utility facilities are underground, utility risk is significant. Obtaining subsurface utility engineering (SUE) data in a timely manner during the pre-procurement phase benefits both the agency and the private entity and the procurement. It also facilitates commencement of negotiations with the utility owners and third parties identified during this process. SUE is an engineering practice that combines civil engineering, surveying, and geophysics to obtain information about underground utilities, and is an integral part of the preliminary engineering process. SUE involves managing certain risks associated with utility mapping at appropriate quality levels, utility coordination, utility relocation design and coordination, utility condition assessment, communication of utility data to concerned parties, utility relocation cost estimates, implementation of utility accommodation policies, and utility design. Different "quality levels" of information are provided by combining these activities with traditional records research and site surveys and utilizing technologies such as geophysical methods and non-destructive vacuum excavation. Costs for SUE services are eligible for Federal participation.

The agency may significantly enhance the likelihood of a successful outcome of the P3 procurement by deciding to make an early investment in SUE. The benefits of early SUE for the P3 project are many, and the higher the "quality level," the greater the benefit. Providing accurate utility information in the procurement documents will significantly reduce the cost that proposers assign to the risk of costs and delays attributable to utility relocations. By identifying the exact location of virtually all utilities ahead of time, relocations can be minimized, and costs and delays caused by cutting, damaging or discovering unidentified utility lines are reduced. These activities, combined with traditional records research and site surveys, and the use of new technologies such as surface geophysical methods and non-destructive vacuum excavation, provide "quality levels" of information.

The agency should determine the extent to which the proposers/concessionaire will be entitled to rely upon the SUE data and site conditions data included in the RFP documents as well as the level of risk associated with utility relocation and site conditions that it will transfer to the concessionaire. One successful practice is for the agency to seek proposers' input early in the procurement process regarding the types of data they believe are most critical to efficiently price the project so that the agency can provide that data during the procurement. By conducting these investigations and providing key information relatively early in the procurement process, the agency can avoid the need to delay the procurement to obtain necessary data, ensuring that price proposals do not include unnecessary contingency for these risks.

For a discussion of issues relating to risks regarding site conditions and utility relocations relevant to P3 projects, see the 2015 NCHRP legal digest entitled "Liability of Design-Builders for Design, Construction, and Acquisition Claims." 68

Almost every P3 transportation project involves multiple government agencies with a stake in the project. In addition, most such projects face a significant risk of project delays and unanticipated costs associated with utility relocations and interfaces with third parties who own facilities affected by the project. Although at least some of this risk can be transferred to the private sector, the agency should seek to reduce the risk to the maximum extent it can.

The first step in mitigating this risk is to identify the project stakeholders, affected utility owners, and other third parties, followed by an assessment regarding the level of risk to the project associated with approvals required from project stakeholders and third parties. In some cases, the agency may be able to transfer responsibility to the concessionaire to obtain permits and other approvals from stakeholders, but in many cases the agency prefers to retain responsibility for interfaces with stakeholders. Regardless of how risk and responsibility are allocated, the project will benefit from early steps taken by the agency to smooth the path for future approvals that need to be obtained from stakeholders.

With respect to utility owners and third parties, significant concerns revolve around the potential for delays to the project if the utility owners or third parties fail to take action required for project construction to proceed in a timely manner. In some cases, project operations are interrelated with third party operations, for example rail transit projects using the same corridor as freight rail operators. The risk of delays relating to project construction can be reduced by entering into agreements that set the rules to be followed to obtain approval of the elements of the concessionaire's design affecting utility and other third-party facilities and to ensure that construction work for such facilities proceeds according to schedule. Similarly, risks relating to project operations can be reduced by third party agreements setting the rules that will apply after completion of construction. Ideally, the agency would start to negotiate these agreements during the pre-procurement phase and continue negotiations during subsequent phases, with the goal of finalizing the agreements well in advance of the proposal due date.

Refer to section 8.1.2 for additional information relating to negotiation of agreements with utility owners and other third parties.

A public outreach plan can serve to both inform the public of the major project milestones as well as communicate the agency's commitment to transparency, thus building confidence in the agency's decision-making process. As mentioned earlier, political risk is a significant risk for many P3 projects, particularly for large projects in jurisdictions with little or no history of P3 procurements. A lack of information in the public domain or even a perception of lack of transparency can have a negative effect on public opinion and consequentially political support for the project.

The Colorado HPTE P3 manual proposes including the following in the agency's public outreach plan:

Most P3 transportation projects face a significant risk of project delays and unanticipated costs associated with ROW acquisition if ROW needs and applicable requirements are not identified and coordinated early in the project planning phase. Even where most of the property required for a project is already under public ownership, it is likely that at least some of the parcels to be obtained will be on the critical path for the construction phase of the project. Although some of the responsibility for acquisitions can be transferred to the private sector, the power of eminent domain can only be exercised by the government. The first step in mitigating this risk is to involve the agency's ROW staff early in the project to help identify the required parcels, determine if the State has early acquisition authority that it can use for the project and set the stage for acquisitions to commence. Some of the early acquisition authorities, found in regulation at 23 CFR part 710, subpart E, allow ROW acquisition to begin before the NEPA process is complete. The State will need to consider each project individually to make a determination about which if any of the early acquisition authorities can be used. If early acquisition authority is not used, ROW acquisition can commence once the NEPA process is complete. The proposers will expect the contract to include an access date for each parcel to be obtained by the agency and information regarding the concessionaire's responsibilities for acquisitions, allowing them to schedule project development. In some cases, the agency might allocate responsibility for ROW acquisition to the concessionaire, particularly for projects where the final design will dictate how much ROW will actually be required. The contractual deadlines for acquisitions to be undertaken by the agency will require input from ROW staff and advisors as well as condemnation counsel, as they are dependent on staffing plans, legal requirements, and court schedules. 69 Furthermore, contract provisions should mitigate the risk that the P3 concessionaire, who may be unfamiliar with the Uniform Relocation Act's restrictions on its ROW activities, inadvertently violates such requirements in its eagerness to accelerate the project schedule.

Various types of funding may be available for the proposed P3 project, including several Federal options as discussed in section 2.4. During the pre-procurement period, the agency should assess available funding sources and take appropriate steps to ensure that the project will be eligible for grant funding, TIFIA and/or RRIF loans and credit assistance, and/or a PAB allocation, to offer the greatest flexibility to the private bidders in structuring their financing solution. As with all projects, the agency should meet with the Build America Bureau and relevant U.S. DOT operating administration representatives to ensure that the Federal partners understand project issues and to obtain advice regarding steps that should be taken to help ensure eligibility for future funding and finance opportunities.

An article discussing FDOT's I-4 Ultimate project highlighted the importance of early and ongoing communications with U.S. DOT regarding TIFIA loans, stating:

"FDOT's early and effective engagement with U.S. DOT from the beginning of the procurement process fostered a positive and productive relationship with U.S. DOT that helped facilitate a relatively smooth negotiation and closing process.

The I-4 Ultimate Project was the first project to implement the new, streamlined TIFIA procedure, for which proposer teams were provided a uniform baseline term sheet upon which to base their assumptions regarding TIFIA loan terms and conditions in their proposals.

FDOT engaged U.S. DOT early in the procurement process and maintained continuous and productive communications with U.S. DOT throughout the RFP development and closing phases. . ., developing a positive working relationship with the TIFIA Joint Program Office.

This relationship facilitated timely and co-operative resolution of the various issues that arose throughout the procurement. Although the best value proposer was responsible for negotiating and finalizing the terms of the TIFIA loan with U.S. DOT, FDOT remained engaged throughout, providing invaluable assistance to I-4 Mobility Partners in reaching final agreement with U.S. DOT." 70

Planning for transit projects pursuing CIG funding includes added steps due to the statutory requirements that must be completed before the project is eligible for and can receive discretionary CIG funding. The transit project sponsor should discuss its proposed schedule with FTA representatives. If the project sponsor plans to award the P3 contract prior to award of the CIG construction grant, it should lay the groundwork for the possibility that a Letter of No Prejudice may be needed to allow work to proceed during the interim period.

The planning process should also consider potential opportunities based on FHWA's authority to conduct experimental programs involving "processes" under the Federal-aid Highway Program 71 and a similar FTA program as discussed below. 72 FHWA has established two experimental programs relevant to innovation that benefit P3 projects. The first is Special Experimental Project (SEP)-14, which allows for the testing of innovative contracting mechanisms and practices. A SEP-14 experiment in the 1990s tested the benefits of design-build contracting for highway projects. Prior to this test, design and construction contracts could not be combined because design contracts had to be acquired through a process requiring negotiation with the most highly qualified firm (essentially the same process required for Federal agency contracts under the Brooks Act). 73 Construction contracts had to be awarded to the lowest responsible and responsive bidder. 74 As a result of the SEP-14 test, Congress amended the law to expressly provide for design-build (and P3) contracting. 75 FHWA headquarters officials in the Office of Infrastructure continue to maintain approval and oversight of SEP-14 experiments.

SEP-15 was created in the early 2000s and is both broader in concept than SEP-14 and focused specifically on P3 project delivery. SEP-15 allows experimentation to test deviations from title 23 statutory, regulatory, or policy provisions, provided that the experimental features are consistent with the overall purpose and intent of the underlying statute, regulation, or policy being tested. Actions explicitly prohibited by statute cannot be the subject of a SEP-15 experiment. The experiment must be consistent with other Federal laws that apply to title 23 funded activities. All SEP-15 proposals are reviewed by a committee of senior headquarters officials and must be approved by the Deputy Administrator. 76 Thus, agencies wishing to propose a SEP-15 experiment must be prepared to have a fairly mature idea of what they wish to do, be able to describe the long-term benefits of their idea, and expect a thorough review process with no guarantee of approval. An example is its use in Florida's I-595, an availability payment project. During procurement, SEP-15 was used to increase the price comparability between proposals by allowing proposers to submit their project proposal to TIFIA during procurement, rather than once a preferred bidder had been selected. Consequently, proposers were able to submit their final proposals including the TIFIA component, making it easier for the FDOT to determine the best value proposer. This approach was subsequently adopted by the TIFIA program as the standard procedure for offering Federal credit assistance in a competitive P3 solicitation. Another example concerns Pennsylvania's Rapid Bridge Replacement, which aimed to replace over 500 structurally deficient bridges. During the procurement, SEP-15 was used to implement a process to speed up the preparation of NEPA documentation and create economies of scale. A list that includes these and other approved SEP-15 experiments may be found on FHWA's website. 77

On May 30, 2018, FTA issued a final rule 78 that would serve essentially the same purpose as SEP-15. Under the "Private Investment Project Procedures" (PIPP) recipients of Federal funding for public transportation projects would be able to request a modification or waiver of specific FTA requirements if the recipient demonstrates that those requirements discourage the use of P3s or private investment. FTA would then have discretion to grant a modification or waiver of such requirement(s) if it determines that:

However, NEPA requirements and any other provisions of Federal statutes would not be subject to modification or waiver.

Finally, the agency should consider the opportunities for training offered by the Build America Bureau and FHWA's Office of Innovative Program Delivery (OIPD) and FTA's Private Sector Participation program. 79

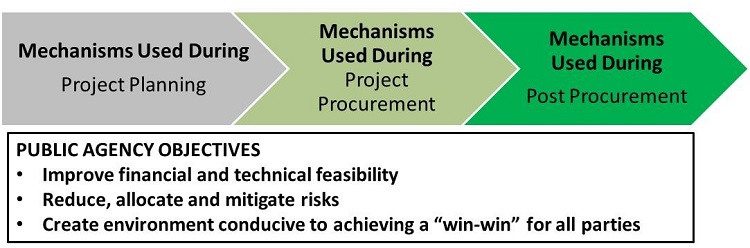

A number of P3 projects have used a PDA model, which involves selecting a concessionaire at the early stages of the project during project planning (see Figure 3). The use of pre-development or comprehensive development agreements are generally a function of State law and State policy. These agencies should consult with agency counsel for consistency with State and local procurement procedures. The concessionaire's scope may include participating in an initial project planning phase with an opportunity to negotiate a subsequent implementation agreement. As permitted by State law and policy, projects that successfully deploy PDAs typically have the following characteristics:

Most industry observers consider the first P3 transactions in the United States to be PDAs, commencing with California's AB 680 Program in 1990, the use of which spread thereafter to the Washington State Department of Transportation's 1993 PPP Initiative, and to the State of Virginia under the Public-Private Transportation Act in 1995. The Texas Department of Transportation, the North Carolina Turnpike Authority, Houston METRO, and the Oregon Department of Transportation, among others, also have used PDAs. The PDA approach has become less common as the market has matured, but continues to be explored by agencies for specific projects.

There is no single way in which PDAs have been deployed, but evolving law and policy, transaction history and lessons learned suggest key attributes, suitability criteria and government sponsor safeguards to optimize value from this tool. The North Tarrant Express (NTE) project provides an example of the successful procurement of a PDA in combination with a toll concession for a portion of the same project that was ripe for development. PDAs may be procured through a qualifications-based selection process or may involve a best value evaluation based on pricing for the initial phase or based on an indicative price for the project. For the NTE project, the selection process included evaluation of the PDA pricing but that component of the proposal was given much lower weight than the technical and financial proposals for the initial scope.