Exhibits

In order to understand the possible tax impacts of different P3 delivery models, it is important to put tax revenue analysis in its proper context. When evaluating whether to move forward with a project, the taxes generated by increased economic activity may be material and represent an important consideration for the public sector sponsor. However, when selecting the preferred project delivery method, the incremental value of tax revenues generated by P3s is typically a small subcomponent of the overall consideration and does not tend to drive the overall decision. With this in mind, below we present a broader discussion on current trends and practices in evaluating projects and delivery methods, followed by an exposition of tax revenue valuation techniques.

Often, public sector decision makers conduct a benefit cost analysis (BCA) to determine whether to proceed with a project. Typically, a benefit cost analysis systematically compares the risk-adjusted economic and/or social benefits and costs of a project or investment proposition. 87 The elements included in a BCA attempt to value the positive and negative impacts of the project from a broad societal perspective, with the objective of determining if, and by how much, the benefits to society outweigh the costs. In addition to financial considerations, these costs and benefits often include environmental, safety, time saving and broad economic/welfare impacts of the project.

Typically, the BCA focuses on evaluating the incremental changes compared to a "base case" in which the project does not occur at all (the "no-build" scenario). The goal of a BCA is to translate the impacts of a project into monetary terms if possible and is usually carried out several times during the development of the project. The steps usually followed by decision-makers to conduct a BCA are summarized below:

The planning activities focus on the definition of a framework for comparing the impacts of the proposed project against the base case. The main elements to define include the technical solution, the analysis timeframe, the geographical focus of the BCA, and the metrics to include in the BCA.

This phase covers the gathering of relevant technical data, such as value-of-time, traffic volumes, projected time savings, vehicle operating costs, safety impacts, and engineering parameters of the proposed project (capital and operating costs for example), and any costs associated with the base case.

Once the key inputs are gathered, a model is developed that attempts to assign financial values to each of the elements being considered. The BCA may often estimate the revenues generated from indirect taxes or incremental economic activity generated by the project's existence. It may involve increased (or decreased) tax revenues from surrounding property taxes, general sales taxes, and income taxes resulting from the project's impact on the local economic activity. Since taxes are a transfer (i.e., a benefit to the taxing authority and an equal cost to the taxpayer), the net effect on overall societal welfare is zero. However, these tax streams can influence the decision to move forward with the project as they represent potential revenue streams to fund future projects and/or initiatives. Typically, the BCA does not consider or compare project delivery mechanisms, making the simplifying assumption that, for the most part, the benefits and costs will be realized by conventional or P3 project delivery, apart from some differences in timing.

An important element of a BCA is the definition of the benefit and cost elements to include in the analysis. As with many types of analysis, this will be influenced by the considerations of the entity performing the analysis and sponsoring the project. This question is important in the U.S., where state and local governments are responsible for most investment in transportation infrastructure. 88 In this case, a state or local sponsor may elect to adopt a more focused scope of analysis than would a nationwide entity, focusing only on the benefits and costs that accrue locally for projects that it is funding on its own. On the other hand, BCA's performed for certain federal grant or credit programs may require a broader view that takes into account regional or national impacts, as appropriate.

Once the project receives the go-ahead based on the results of the BCA, the public sector entity responsible for the project must determine its preferred delivery method. This analysis often includes both qualitative and quantitative analytical methods. While there is a broad range of "traditional" project delivery methods available to U.S. entities, this paper will focus on the generalized choice between a P3 project delivery and whatever the local "traditional" project delivery method would be.

The decision on whether to pursue a P3 or another project delivery method is frequently supported by a common analytical methodology - the Value for Money (VfM) Analysis. At its core, the traditional VfM methodology attempts to evaluate the net present value 89 of the risk-adjusted lifecycle costs and revenues (if appropriate) to the project sponsor of delivering the project though conventional, P3, or other means. 90 The option that has the lowest net lifecycle costs (or highest net revenues) is the one that is said to show the highest value for the money spent assuming that other factors - such as schedule or quality of service are the same under the delivery methods being compared. In many infrastructure markets with a history of performing VfM analysis, qualitative elements like regulatory factors, risk management, and an analysis of the respective capabilities of the proposed parties are often included in the VfM analysis. This is done to ensure that a "better" product that might come at an increased financial cost still demonstrates Value for Money.

We note that the discussion below focuses on quantitative elements of Value for Money in general terms, but does not define specific methods of analysis. This reflects the findings in discussions with advisors and sponsors while researching this paper that, unlike other countries like Australia 91, Canada 92, and the UK 93, where VfM follows very defined and prescribed methodologies, the US market appears to be moving in a different direction. Instead of focusing on defining a methodology that will derive one number that will define how much value for money is expected to result from a specific project delivery method, US Value for Money analysis is more focused on understanding the key "trade-offs" (both qualitative and quantitative) that might be associated with a given project delivery methodology. Based on discussions of a roundtable of experienced advisors and procuring entities convened for the purposes of this paper, 94 a leading practice is to develop a matrix of considerations and tradeoffs associated with the various project delivery methods under consideration, and to use that matrix with decision makers and stakeholders to make the final project delivery decision. Many of the elements that would be included in this analysis are beyond the tax-focused scope of this paper, so the balance of the paper will focus on the quantitative elements that typically involve tax revenues.

Typically the first steps of a VfM analysis examine two primary scenarios - (1) project delivery through traditional public means (i.e., the Public Sector Comparator (PSC)), and (2) an estimate of what a P3 bid will be (i.e., the Shadow Bid).

The PSC is the procuring agency's estimate of what the lifecycle costs of the project will be using a conventional project delivery method. The Shadow Bid is an estimate developed by the procuring agency and its advisors of what a private sector P3 bid would likely be. The Shadow Bid takes into account the financing instruments likely to be selected by a private bidder, as well as expected efficiencies provided by the private sector's involvement. As described above, Value for Money globally has often been summarized as one number demonstrating the Value for Money of the project. This can be seen in Exhibit H below:

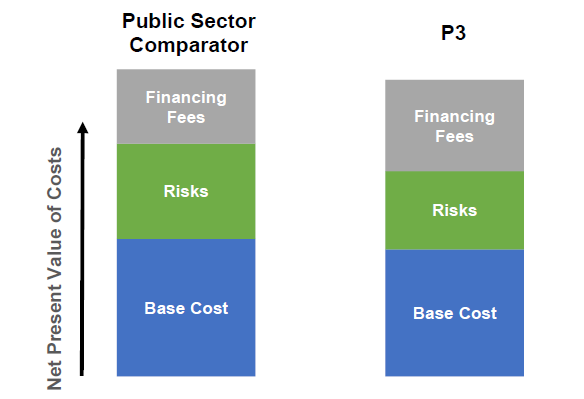

|

Exhibit H above describes the net present value of costs, comprised of Base Cost, Risks, and Financing Fees, for the Public Sector Comparator and a P3. The aggregate net present value of costs is lower for the P3 than the Public Sector Comparator, reflecting the Value for Money differential.

In addition, one method of analysis that is receiving increased acceptance, is to examine the "value for money", or savings of one method over another, generated in each year. This enables the procuring authority to understand the potential yearly impacts on its budget in a given year, and is particularly applicable to availability payment projects. It also provides the ability to analyze any trends in benefits achieved over time. An example of this analysis is shown in Exhibit I below.

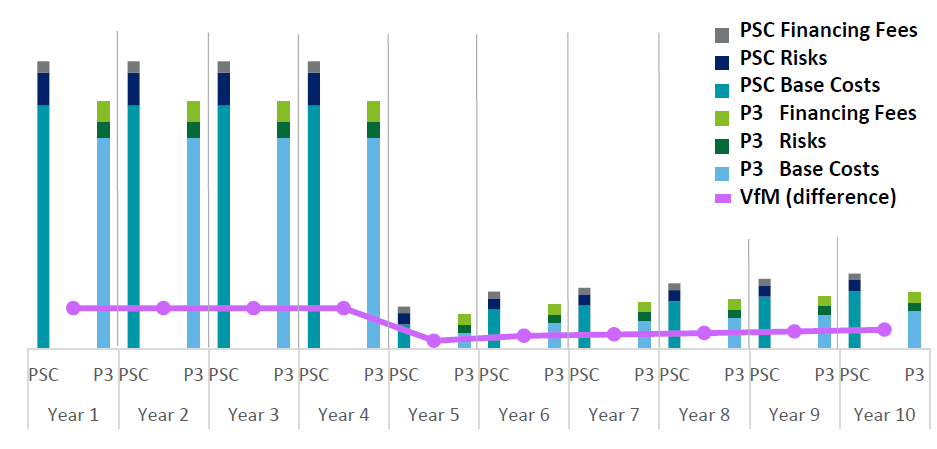

|

Exhibit I above describes the Value for Money and its three components (Base Cost, Risks, and Financing Fees) as a bar chart over a time period (in years) and compares the PSC with the P3 project delivery. Annual costs associated with the P3 project delivery are lower than the PSC, resulting in a positive VfM throughout the time series.

A few considerations have arisen regarding the outputs of traditional VfM analysis:

The discount rates used during the VfM analysis can materially influence the analysis outcome. Higher discount rates put less value on future cash flows, thus more strongly emphasizing upfront project costs, while the inverse is true of lower discount rates.

There is an ongoing academic debate regarding the selection of the discount rate 95 that is beyond the scope of this paper. However, guidelines provided by several countries where P3s are deployed suggest that the discount rate could be comprised of two main components and applied to both the PSC and the Shadow Bid 96:

Some awarding authorities prefer to use different discount rates for each scenario, 97 using a higher discount rate for the costs associated with the Shadow Bid to reflect the risk-shifting to the private sector associated with the P3 project delivery. FHWA's P3-VALUE 2.0 analytical tool and its Value for Money Guide suggest that lifecycle performance risks shifted to a P3 concessionaire may be calculated as a separate component based on the risk premium associated with the weighted average cost of capital of the P3 Shadow Bid. Alternative methods include using a Competitive Neutrality Adjustment to the calculation to reflect the value of this risk-shifting, or adjusting the cash flows and performing scenario analysis to analyze the range of financial results that may arise from different project delivery methods. As stated above, the subject is still a matter of debate and results in different approaches across countries and even across procuring entities and advisors within the same country.

Furthermore, methodologies surrounding the creation of the Shadow Bid may depart from the practices actually in use when P3 bidders submit bids in real procurements. 98 For example, some advisory practitioners may apply different discount rates to the project's revenues and costs, reflecting the different risk profiles and estimation certainty of each. This is not typically a practice seen in bid models. Also, P3 bids often reflect a revenue projection exercise that benchmarks all revenues (and consequently the bearable costs of the project) against a higher estimate than the Shadow Bid. The typical revenue assumption for a P3 bid uses the revenues expected with 50 percent likelihood (P50), reflecting the potential upside of the project, while the Shadow Bid created by the public sponsor often uses the revenues expected with 90 percent likelihood (P90). FHWA's P3-VALUE 2.0 analytical tool uses P50 revenue estimates for the Shadow Bid and incorporates a revenue uncertainty adjustment that accounts for the P90 perspective of public sponsors.

Finally, given the difficulties inherent in the public sponsor's estimation of a P3 Shadow Bid, some U.S. decision makers have elected to deemphasize the Shadow Bid in favor of a more robust PSC. The robust PSC attempts to more precisely estimate the price at which the public sector could traditionally deliver a project at an accepted level of quality. The estimation gives more attention to the required warranties, insurances, and other risk-protections that the public sector would reasonably need to incur to develop the project. This PSC is then effectively used as an auction "reserve price" that the P3 entity must outperform, or else the public sector will deliver under traditional methods.

Even after accounting for the differences in baseline costs, retained risks, and financing costs, there may still be some adjustments required to provide a more even comparison of the PSC and P3. One additional factor includes tax streams foregone by the public sponsor when it chooses to use traditional project delivery. A Competitive Neutrality Adjustment (CNA) is one way to model these nuances, and in particular for the purposes of this paper, the value of tax streams. The result of the CNA is a PSC that more fully reflects the foregone revenues and expenses associated with traditional project delivery.

The CNA sometimes attempts to resolve the potential distortions to the VfM arising from the fact that a project delivered via a traditional project delivery is not completely comparable to a P3. P3s often have different characteristics with respect to cost certainty, overall project quality and additional tax revenues. Concession agreements contractually obligate the P3 owner to deliver on schedule (with liquidated damages if not), fulfill maintenance requirements over time, and to use equity or reserve accounts in the event of cash flow shortages. (These factors may be addressed separately in a "lifecycle performance risk" estimate, as suggested by P3-VALUE 2.0 and FHWA's Value for Money Analysis Guide.) In addition, the P3 entity's owners generally pay taxes that would not have been realized had a public project delivery been undertaken. Taxes are the key adjustment reflected in the P3-VALUE 2.0 tool.

Incorporating the CNA into the VfM analysis allows these considerations to inform the decision criteria. In its simplest form, and only with respect to taxes, 99 a CNA attempts to account for the additional tax revenues that are received by the public sector because it used a P3 project delivery instead of a traditional project delivery. In this case, the taxes that are foregone because the public sector used a traditional project delivery mechanism represent an opportunity cost to the public sector. 100 Analytically, this is typically handled by adding this as an "opportunity cost" of lost tax revenues to the Public Sector Comparator, on a net present value basis. These concepts are demonstrated in Exhibit J.

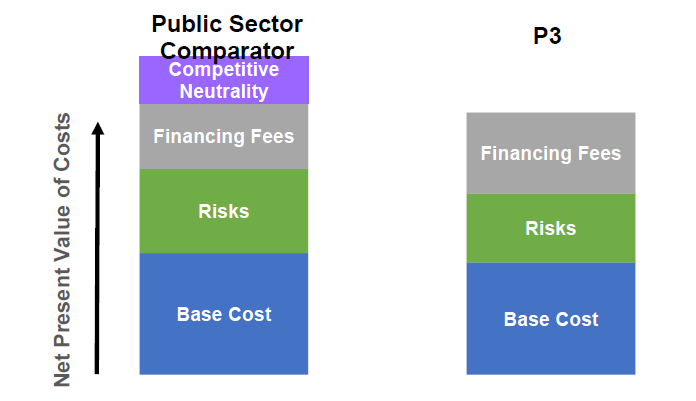

|

Exhibit J above expands upon the chart described in Exhibit H by comparing the net present value of costs for a Conventional Project Delivery and a P3 Project Delivery. However, in this case, an additional element, Competitive Neutrality, is added to the Conventional Project Delivery option to reflect the opportunity costs of foregone taxes, increasing the Value for Money of the P3.

Specifically, if the P3 concessionaire's owners pay taxes (e.g., taxes on income or dividends), the present value of those taxes are calculated and added as a cost to the PSC to offset the tax income stream that is foregone by not pursuing a P3 project delivery. A comprehensive treatment of taxes generated by a P3 would also consider the tax revenues of any taxable debt issued to finance the P3, as the public sector would generally use tax-exempt debt. Unless the debt issued is tax-exempt, it would be expected that any interest income from the debt would be subject to a combination of local, state, and federal taxes. Practically, though, many U.S. transportation P3s have been majority-financed by federal credit (e.g., TIFIA) and private activity bonds (PABs), which are both tax-exempt forms of debt. (Federal credit programs do not pay taxes on their interest income,) Furthermore, the additional tax income from investors in taxable debt is partially offset by the larger interest deduction claimable by the P3 due to higher interest rates for taxable debt.

Like the VfM that it contributes to, the CNA is subject to subjective decisions in its application. This is because the public sponsor must make assumptions about the tax profile and strategy of likely bidders, which may not reflect the reality of actual bids, as well as the revenues and costs of the P3. The CNA may be more meaningful when used to assess availability payment P3s rather than revenue risk P3s. This is because under an availability payment structure, revenues are contractually agreed upon, whereas under a revenue risk structure revenues depend on actual traffic volumes. Hence, the uncertainty of the tax stream under the former is potentially less than under the latter.

The assumptions and calculations performed in the VfM and its CNA can vary depending on who is conducting the analysis. Whether to use different discount rates for revenues and costs, whether to factor in the accelerative benefits of P3s, whether to incorporate a project's social benefits, and which taxes or other cash flows to include, are in the end up to the discretion of the public sponsor. Ultimately, decision makers use the VfM as a tool to assist in making project delivery decisions based on their considerations at the time. Certain methodologies may better fit the objectives of a particular public sponsor at a particular time.

One key motivation for using a P3 delivery method, particularly in the case of revenue risk transactions, is the potential for additional capacity that it creates for procuring entities to pursue projects. P3 delivery mechanisms for revenue risk transactions can bring in outside capital for investment, lower the upfront government contribution, move projects off of the government balance sheet, potentially avoid the need to establish or expand a public authority, and contractually obligate certain performance and quality standards without requiring the allocation of funds to satisfy ongoing maintenance requirements. Projects may get built that would not otherwise be built given the public sponsor's fiscal constraints, expanding and accelerating the portfolio of projects that can be pursued. Benefit-Cost Analysis (rather than VfM) methodologies can be used to analyze these projects by comparing them to a "no build" PSC, or one that is significantly delayed. FHWA's P3-VALUE 2.0 analytical tool and guide demonstrate how such comparisons may be made. The decision of how to structure the PSC will depend on the financial and political realities of the public sponsor at the time.

Similarly, which taxes to include in the CNA is a subjective decision for the public sponsor. Based on discussions with practitioners, 101 a common practice is for the CNA to only include taxes that inure to the public sponsor's level of government. For example, a state department of transportation that benefits from general fund appropriations may not wish to consider federal income taxes, but may include state income taxes in its CNA. 102 Other state or local agencies may not include state income taxes if they do not receive them. Furthermore, a self-supported state Turnpike Authority may choose to not include any taxes or to perform a CNA. On the other hand, there have been examples where the CNA included all levels of taxation due to the project's funding by federal, state, and local sources. 103 We note that removing non-inuring taxes from the analysis would tend to weaken the case for a P3, whereas including all levels of taxation would lead to a larger "opportunity cost" adjustment to the CNA.

Regardless of the methodology employed, experience and research indicate that the impact of the state and local taxes associated with the CNA on the VfM will be small compared to differences between the PSC and Shadow Bid in terms of base costs, financing fees, and retained risks. However, as demonstrated in the example tax calculations in the Appendix, much larger impacts may be estimated if Federal income taxes are included in the CNA estimate.

A P3 can be structured in several different ways, and a number of decisions may be made by taxing authorities or government entities as to which taxes to waive or reimburse to the P3 concessionaire. One key principle for public sector sponsors to consider in making tax decisions is that there will be a tradeoff between the value the public sector receives directly from the P3 project and taxes the P3 concessionaire or its owners are required to pay. These taxes factor into the P3 partner's financial model as a cost, and therefore increase public sector upfront costs (contributions or milestone payments), availability payments, or toll rates that must be paid, or reduce any up-front payment the concessionaire may make. Accordingly, the decision a procuring authority makes (to the extent it makes decisions about the taxes to which a P3 is subject) is whether it wants to receive the value in the form of taxes from the P3, reduced cost in upfront or availability payments, reduced costs for facility users, or an increased up-front payment. Exhibit K depicts this trade-off.

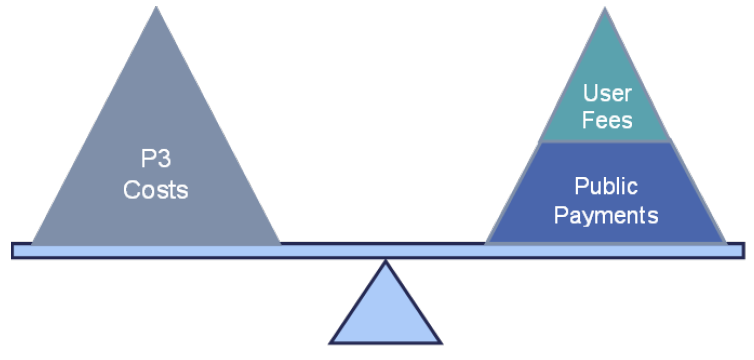

|

Exhibit K demonstrates the balance that an awarding authority must preserve for a P3 project delivery. The costs associated with the P3 need to be balanced with the proceeds from user fees and/or public payments.

Generally, the direct taxes paid by a P3 concessionaire's owners, if they are included in the financial model, will be calculated by the model based on the model's underlying assumptions for the tax base and rate. For public sponsors wishing to analyze or estimate tax revenue streams, this can be a very helpful tool. Various scenarios can be run in the model to analyze the impact of different economic and performance factors on the tax revenue streams. This type of scenario analysis can often be used to develop risk-adjusted expectations of the tax revenue streams. For example, adjusting key project variables will result in a range of revenue streams, which can be combined (generally using a probability-weighting approach) to develop an "expected" revenue stream. In a toll concession, economic activity, traffic, toll rates, inflation, project performance, and other demand-based metrics can be adjusted to produce yearly revenue streams under varying conditions. In availability payment concessions, revenues stem from upfront milestone payments and a series of availability payments that are calculated to meet the private sponsor's required rate of return. Therefore the tax revenue generated from these projects will not change as much in a scenario analysis based on economic variables. However, a project sponsor may wish to consider modeling scenarios based on private partner performance and assumed penalties for non-performance.

Private sector bidders also incorporate calculations for direct taxes into financial projections. As discussed at length in Sections 2 and 3, the legal structure of not only the P3 vehicle but also the project partners will play a role in the effective taxes paid by the P3 concessionaire. In theory, one could come up with a 'best guess' tax rate by combining the various tax rates expected to be paid by project partners and weighting them according to each partner's equity share. In practice, financial models will often simplify this calculation by assuming a 35% corporate tax rate for the project. The simplification allows for a standardized metric that partners use to determine their relative tax burden. If taxes are included in the model, project returns are generally calculated on both before-tax and after-tax bases to allow each investor to analyze project cash flow based on its tax status.

For indirect taxes calculated by the public sector, the modeling exercise may involve developing a secondary model to estimate tax revenue streams. This model would use the project model as an input, and would then perform additional calculations based on the results and economic activity implications of the project model to generate a tax revenue stream. Development of this model would require the development of assumptions for relationships between the tax base and the P3 project's activity. For example, to model the impact of the P3 project on local real estate values, an assumption could be made that for every x% increase in traffic, there is a corresponding y% increase in assessed property values in the area that is z miles on either side of a road. The project model's assumptions for traffic would then feed into the secondary model, which would calculate estimated assessed values and property taxes in each year. A scenario analysis can then be performed to develop a range of property values under various conditions, and an "expected" revenue stream can then be calculated.

87 http://www.dot.state.mn.us/planning/program/benefitcost.html

88 National Association of State Budget Officers State Expenditure Report, 2015

89 The net present value is the difference between the discounted value of the revenues of a project and the discounted values of its costs. For an explanation of the calculation methodology to derive the discounted value, please see section 4.3.3 Discounted Values, below.

90 FHWA - P3 Value for Money Primer

91 https://infrastructure.gov.au/infrastructure/ngpd/files/Volume-5-Discount-Rate-Guidance-Aug-2013-FA.pdf

92 http://www.p3canada.ca/~/media/english/resources-library/files/revised/p3%20business%20case%20development%20guide.pdf

93 https://www.nao.org.uk/successful-commissioning/general-principles/value-for-money/

94 Held on March 30, 2017 at FHWA Office in Arlington, VA.

95 http://www.eib.org/epec/resources/publications/epec_value_for_money_assessment_en

96 Ibid.

97 https://www.oecd.org/gov/budgeting/45038620.pdf

98 FHWA Roundtable with Practitioners, held March 30, 2017, at FHWA facilities in Arlington, VA

99 Competitive Neutrality Adjustments may consider more than the tax implications of a P3. They may also attempt to place a value on the risk-shifting over the project lifecycle, freed-up financial capacity, and other items that may be specific to a project. Often, these other factors outweigh the impact of the taxes. A robust discussion of risk-estimation or CNA methodologies is beyond the scope of this paper. The reader may consult FHWA's Value for Money Analysis Guide for a more detailed discussion of risk valuation.

100 Guidance for Quantitative Procurement Options Analysis Discussion Paper, Page 19, Partnerships British Columbia

101 FHWA Roundtable Discussion with Practitioners, held March 30, 2017 at FHWA facilities in Arlington, VA

102 I-595 Business Case Analysis**

103 Presidio Parkway Business Case Analysis