List of Figures

List of Tables

This chapter describes how governments set the policy, goals, objectives, and key performance indicators that form the basis of the policy case for a project. These are linked to the business case for a value capture technique through the allocation of costs and risks. This chapter explains how policy makers at the State and local level can achieve alignment of their policy objectives with the business and financial case for value capture techniques. It also discusses how this process can be enhanced through involving stakeholders in the planning process.

It is important that the rationale for pursuing value capture techniques be integrated into an overall coherent policy vision for transportation, mobility, and land use. For value capture to be successful, there should be clearly articulated policy goals with broad stakeholder buy-in. The type of value capture technique pursued should be directly related to achieving those goals. At a general level, the policy planning process involves the articulation of broad policy goals, which should be translated into concrete policy objectives and measured through key performance indicators (KPI).

Policy goals refer to a government's broad objectives for policy making. Goals can be defined as statements that describe the fundamental economic, social, and environmental outcomes that a jurisdiction is aiming to achieve through its activities across all sectors (not just transport). As they relate to transportation and development, goals typically fall into broad categories such as the following:

Example 19 shows the policy vision for the Bel-Red Street Network in Washington State.

Example 19: Clear Identification of Vision and Goals in the Bel-Red Street Network

The corridor connecting Redmond, Bellevue, and Seattle in Washington State is one of the fastest-growing areas of the Pacific Northwest. With the Central Puget Sound Regional Transit Authority, known as Sound Transit, expanding the light rail network across metro Seattle, the city of Bellevue saw an opportunity to promote transit-oriented development around the future light rail line - the Bel-Red Street Network - to generate maximum benefit from it. The city set up a community steering group to guide planning and set overarching goals. The steering group developed a detailed set of goals and targets to transform the 900-acre site into mixed-use, transit-oriented neighborhoods, while improving the environment and creating thousands of new jobs and housing units. The vision defined by the steering group consisted of the following six goals:

This case is discussed in more detail in Appendix Section II.

The next step in developing the policy case is to translate broad policy goals into specific objectives for various aspects of the transportation program. 254 Table 11 shows an example of broad goals linked to specific objectives.

| Area | Economic Objectives | Environmental Objectives | Social Objectives |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regional Road Network | Improved economic growth throughout the region | Reduced pollution and negative externalities from driving | Better, lower-cost mobility throughout the region |

| Municipality | More efficient connections to the region to spur development | More livable, less polluted community | Improved standing of the municipality on measures of social equity |

| Corridor | Less congestion due to improved transit-oriented development | Increased share of active modes on corridor | Improved access to services and housing for all socioeconomic groups |

| Interchange | Better intermodal connections at interchange | Active modes and transit incorporated into interchange facilities | Better affordability incorporated into any interchange-adjacent development |

In order to monitor the achievement of objectives, KPIs are used to track progress. KPIs can be tracked against specific value capture methods to measure the extent to which they are helping achieve a government's goals and objectives. Most jurisdictions will have guidelines for developing targets and KPIs. The following SMART 255 criteria are commonly used to guide practitioners in developing KPIs:

KPIs should incorporate measures that are recognized as reliable and appropriate. This may include meeting legislative criteria or standards set by professional bodies. Where new measures are proposed, consideration should be given to consulting with the relevant stakeholders to ensure a robust indicator is set and to reduce the likelihood of disputes at a later stage. Further discussion on stakeholder consultation is discussed in Section 10.4.

Because value capture techniques rely both on public and private coordination, government support alone is not sufficient for their success. There should also be significant private sector support for value capture to work - both from the general landowners (not to be confused with the general public) and the private developers. For the private sector to be supportive, the value capture proposal should convey an appealing business case from both a public and private perspective.

A key feature of a strong business case is that it be fair and favorable from both a public and private perspective. This means it should have an appropriate distribution of costs, benefits, and risks between both parties. The process of developing a business case for a new value capture initiative requires first defining the investment and then the optimal distribution of costs, benefits, and risk between public and private parties.

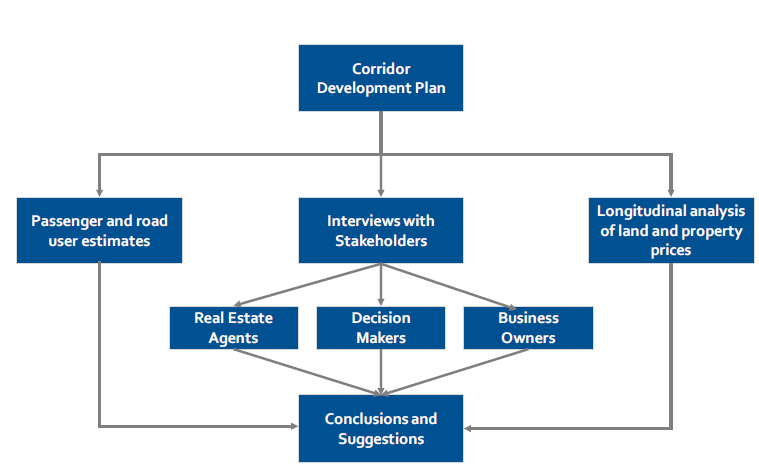

Figure 4 shows an example of the process of developing a business case for a value capture initiative. Developing the business case requires gathering both quantitative and qualitative data to understand the full perspective of the costs and risks associated with a project and the associated value capture initiative. A project proponent can then determine an acceptable cost and risk-sharing approach to both the private and public sectors.

Step One: Gather Required Project Information

Developing a business case for a value capture initiative first requires assembling all required corridor information. This includes "hard" data such as user estimates and property market analyses, as well as "soft" data gained through interviews with potential investors and market stakeholders. Much of this information goes into the development of economic impacts by category. In some cases, this may be accompanied by a more formal cost-benefit analysis or even a more general economic impact analysis highlighting non-land-based benefits to parties.

Project-specific information includes data on costs and constructability, such as the following:

Step Two: Determine Project Risks and Appropriate Risk Sharing

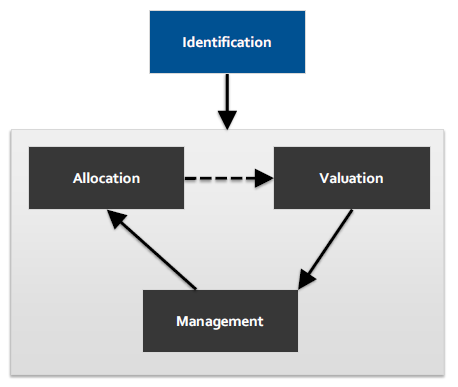

Following are the four major steps in risk assessment, shown also in Figure 5:

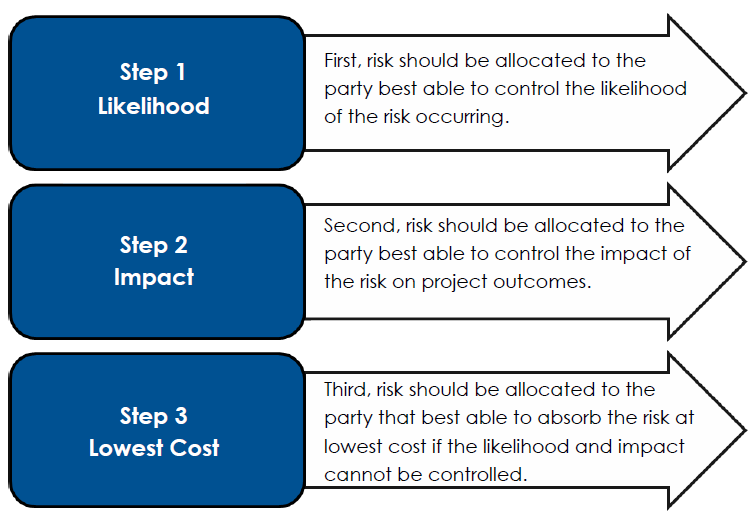

The risk identification and valuation exercise is interwoven into the risk allocation and management process. Figure 6 illustrates considerations relevant to ensuring risks are allocated appropriately. After the risks and costs are defined, valued, and allocated, the next step is to develop a funding plan for the project based on identified public and private funding needs.

Step 1 |

First, risk should be allocated to the party best able to control the likelihood of the risk occurring. |

Step 2 |

Second, risk should be allocated to the party best able to control the impact of the risk on project outcomes. |

Step 3 |

Third, risk should be allocated to the party that best able to absorb the risk at lowest cost if the likelihood and impact cannot be controlled. |

Detailed guidance on business case development, including risk allocation, can be found in FHWA's Guidebook for Risk Assessment in Public Private Partnerships. The approaches described in this guide are geared toward P3s, but can be easily adapted for other methods of alternative delivery, including value capture.

Explore in Detail

Guidebook for Risk Assessment in Public Private Partnerships

Federal Highway Administration, December 2013.

Preliminary planning and design should always be part of the project delivery process and can lead to more efficient project delivery. Specific preliminary design steps include many early engineering tasks, risk analyses, environmental analyses, and other reviews, such as land ownership, topography studies, traffic studies, financial analyses, reviews of hazardous materials, estimates of materials and labor needed for final design, and utility reviews. 256

An agency can realize significant project delivery efficiencies if planning and design occur in tandem with the environmental review process, especially since many preliminary design tasks are linked to the information needed for this process. For example, through preliminary planning design, an agency can determine high-level project location and design ideas, as well as potential alternatives, each of which feeds into environmental review.

For additional environmental review and preliminary planning and design process details, refer to Chapter 4 in the FHWA Office of Federal Lands Highway Project Development and Design Manual.

Explore in Detail

Project Development and Design Manual Section 4: Conceptual Studies and Preliminary Design

Federal Highway Administration, July 2012.

It is critical for sponsors of transportation projects involving value capture techniques to involve stakeholders and foster public involvement. Stakeholder involvement can help improve the project's benefit to the community, municipality, and/or the State, as well as to those specific stakeholders. It can also help mitigate some of the negative impacts of the project and build stakeholder support.

The FHWA Office of Planning, Environment, and Realty describes stakeholder involvement and the public participation process as follows:

Public participation is an integral part of the transportation process that helps ensure decisions are made in consideration of and to benefit public needs and preferences. Early and continuous public involvement brings diverse viewpoints and values into the decision-making process. This process enables agencies to make better informed decisions through collaborative efforts and builds mutual understanding and trust between the agencies and the public they serve. Successful public participation is a continuous process, consisting of a series of activities and actions to both inform the public and stakeholders and to obtain input from them that influences decisions that affect their lives.

The public, in any one area or jurisdiction, may hold a diverse array of views and concerns on issues pertaining to their own specific transportation needs. Conducting meaningful public participation involves seeking public input at specific and key points in the decision-making process on issues where such input has a real potential to help shape the final decision or set of actions.

Public participation activities provide more value when they are open, relevant, timely, and appropriate for the intended goal of the public involvement process, providing a balanced approach with representation of all stakeholders and including measures to seek out and consider the needs of all stakeholders, especially those that are traditionally underserved by past and current transportation programs, facilities, or services. 257

Stakeholders may express objections to the project and/or the value capture technique used in the project. For instance, stakeholders had objections to the Capitol Crossing project (see case study in Appendix Section V) because of its impact on surrounding real estate and the belief that the District of Columbia's compensation for the air rights was not adequate. Therefore, the approaches to addressing and managing stakeholder needs that apply to transportation projects generally also apply to value capture-related projects. Resources on these approaches are noted at the end of this section.

Stakeholders consist of people, groups, and organizations. They take on different roles in the project development process, working with the sponsor of the value capture-related project. They include the following:

In the case of transportation value capture projects, it is common for the sponsor to negotiate with several stakeholders to realize a project. In the case of transit projects, it is common for the transit agency to require the local municipality to provide its regulatory approval and for developers to participate in a joint development project or donate land to achieve project benefits. 258

The process to involve stakeholders, hear their concerns and, in some cases, negotiate with them, takes place in a number of forums. These include meetings and hearings, which are typical in an environmental or planning process that mandates the number and format of such events. It can take the form of legislative deliberations, as in the case of the Bozeman impact fees. It can also take place in the form of referenda, as in the case of U.S. Highway 63 when local citizens along that alignment voted in favor of the project, allowing the special purpose transportation corporation to move ahead with it. Stakeholder involvement can also take the form of a legal process, as happened in Bozeman when a group opposing the impact fee sued the city.

Stakeholders also use social media to express their views on projects. The FHWA has developed recommendations on virtual public involvement, which are referenced at the end of this section.

The stakeholder involvement process can take time and can potentially delay a project. Scheduling and holding meetings can add time, especially if additional meetings are required that were not included in the original project development process. Sponsors need to consider this timeline in the context of other project timelines. It is important that project sponsors consider the time required for stakeholder involvement as an opportunity to hear and address public concerns and build support for the project.

Increasing stakeholder buy-in sometimes also comes at a financial cost to project proponents. For instance, some transit value capture projects may require that, in return for increased zoning density, developers make a portion of new housing affordable. In the case of the Atlanta BeltLine, that project's financial capacity was limited by the requirement that some of the TIF revenues be shared with the Atlanta School District. In the case of Capitol Crossing, the District of Columbia prevented the developer from closing parts of I-395 during construction, increasing project costs.

A best practice in development for many transportation projects, especially value capture-related ones, is that the sponsors anticipate and build in a variety of mechanisms to incorporate stakeholders. Sponsors should expect to hear opposition to the project and be prepared to negotiate with stakeholders as is financially, legally, and politically possible. As with any negotiation process, especially in public forums, sponsors need to recognize that not all concerns may be able to be adequately addressed.

Explore in Detail

Center for Accelerating Innovation: Locally Administered Federal-Aid Projects: Stakeholder Partnering

Federal Highway Administration, 2019.

Office of Planning, Environment, and Realty: Virtual Public Involvement

Federal Highway Administration, 2019.

Public Involvement/Public Participation Portal

Federal Highway Administration, 2019.

254 "Defining Goals, Objectives, and Targets," Australian Transport Assessment and Planning, June 22, 2018, www.fhwa.dot.gov/ipd/value_capture/resources/value_capture_resources/value_capture_implementation_manual/ch_10.aspx.

255 George Doran, "There's a S.M.A.R.T. Way to Write Management's Goals and Objectives," Management Review, vol. 70, no. 11, 1981, pp. 35-36.

256 "Clarifying the Scope of Preliminary Design," Federal Highway Administration Center for Accelerating Innovation, July 18, 2016, www.fhwa.dot.gov/innovation/everydaycounts/edc-1/prelimdesign.cfm.

257 "Public Involvement/Public Participation," Federal Highway Administration Office Planning, Environment, and Realty, www.fhwa.dot.gov/Planning/public_involvement/.

258 Sasha Page et al., Transit Cooperative Research Program (TCRP) Report 190: Guide to Value Capture Financing for Public Transportation Projects, Transportation Research Board, 2016, 44-46.