List of Figures

List of Tables

Once a public agency has identified a project that meets public policy objectives, the next stage involves developing a plan for funding and maybe financing the project. This first section of this chapter presents an overview of the range of different funding and financing options available to State and local governments. The second section provides some considerations for government practitioners determining whether value capture techniques may be appropriate for their specific project.

Developing a funding and financing plan involves identifying the sources for capital costs and O&M costs.

Developing a funding and financing plan for an infrastructure project is one of the key steps within the planning process. These plans should consider the following questions:

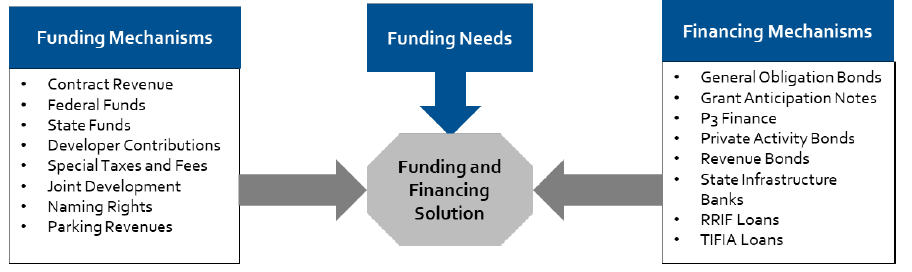

The conceptual distinction between funding and financing sources is explained in Sidebar 2, and Figure 2 provides examples.

Although the terms funding and financing are often used interchangeably, they are separate concepts.

Funding refers to the various sources that are available to help pay for an infrastructure investment. Funding sources may be available immediately (such as Federal or State funds) or may materialize during the later years of the project's life (such as tolls, farebox revenues, or incremental tax revenues).

Financing refers to the set of arrangements that ensure there is enough cash up front or during appropriate phases of the project to pay for the capital costs of the new infrastructure. Financing arrangements can involve debt (including bond financing or bank loans) or equity capital provided by private developers. Issuing bonds results in interest and principal payments or debt service, which are paid for throughout the life of the project. Through financing, future funding sources can pay for the current investment.

Funding and financing mechanisms provide funding and financing solutions to funding needs. Funding mechanisms include contract revenue, federal funds, state funds, developer contributions, special taxes and fees, joint development, naming rights, and parking revenues. Financing mechanisms include general obligation bonds, grant anticipation notes, P3 finance, private activity bonds, revenue bonds, state infrastructure bonds, RRIF loans, and TIFIA loans.

A funding and financing plan will typically include a combination of traditional and innovative funding and financing sources.

Table 1 provides a non-exhaustive overview of traditional and innovative funding and financing sources. As part of developing a financial plan for a project, practitioners are encouraged to consider all potential funding sources and financing techniques. A good starting point is typically to examine which Federal and/or State funding and financing sources may be available for the project and then to estimate the funding gap for which more innovative sources can be considered. The development of a financial plan often combines different funding and financing sources, requiring practitioners to apply resourcefulness and creativity.

| Approach | Funding Sources | Financing Mechanisms | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct System Revenues | Other Funding Sources | ||

| Traditional |

|

|

|

| Innovative |

|

|

|

Some value capture techniques, such as joint development, are associated with P3s, a form of project delivery and risk transfer used in many types of infrastructure projects, including transportation. There are important similarities and differences between these, especially in the procurement process, with P3 procurements often following a more structured process, as described in Sidebar 3.

Public agencies use P3 techniques to develop and operate transportation infrastructure, including toll roads and transit facilities. The application of certain value capture techniques can be considered P3s. When planning and discussing a project with stakeholders, it is important to be aware of the similarities and differences between the two.

Key Similarities: P3s involve the transfer of certain risks between the public agency and infrastructure developers, such as for design, build, finance, and O&M. Many State departments of transportation (DOTs) have undertaken P3s for major highway projects, including those in California, Florida, Texas, and Virginia. Some transit agencies have utilized P3s as well, including projects in Denver, CO, and the Maryland suburbs of Washington, DC.

Value capture joint development projects are a form of P3 in which a transportation agency selects a developer as a partner. Most often, the developer is not building the transportation facility, but some type of development with the public agency benefiting financially and/or through an in-kind contribution as discussed above. It may involve some type of compensation and/or exchange of value.

Key Differences: P3s generally involve a highly structured procurement that ends with the selection of one firm or a group of firms to deliver the transportation project. Value capture procurements may be highly structured or they may be closer to qualifications-based selection processes, in which the firm or consortium of firms is selected based on its expertise or concept, with the final agreement negotiated once the project parameters have greater clarification. Also, a joint development may include one or more developers. The Denver Union Station joint development, for instance, had multiple developers.

Furthermore, other value capture techniques, such as TIF districts, special assessment districts (SADs), and business improvement districts (BIDs), may involve one developer or a number of them. With these techniques, there is not usually a selection process but an approval process that may include one landowner or a group. In the case of TIF, some municipalities provide this benefit to one developer as part of an agreement to pay for necessary infrastructure improvements. These agreements are usually derived from negotiations and not a fully competitive process.

Asset Recycling: Asset recycling is an approach that relates to and/or overlaps with P3s. In asset recycling, existing public use infrastructure is sold or leased to a private party. The government uses the monies to pay for the improvement of other infrastructure assets. This technique has been used in Australia 13 and is now in use in the United States. Often under the arrangement, an existing asset is leased to a private party that then enhances that asset, such as in the U.S. 36 Express Lanes project in Denver, CO. 14 Asset recycling is often considered a form of P3. In some circumstances, it could also be considered a form of value capture. Since this Manual focuses on value capture techniques that generally have a link to real estate markets or locational advantages, asset recycling is not discussed here. FHWA's website contains informational material on asset recycling at: https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ipd/fact_sheets/value_cap_asset_recycling.aspx.

Federal and State funding and financing options typically have limitations on the extent to which they can pay for project costs.

Federal and State disbursements often require a State or local match, typically in an 80:20 ratio. Sometimes, State or local governments may struggle to secure the required matching funds. In these cases, the following Federal-aid matching strategies are available:

Federal financing mechanisms may also be limited in the extent to which they can finance project costs. Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (TIFIA) loans, for example, can generally finance up to 33 percent of eligible project costs. 17 The specific requirements of Federal and State grants and programs present opportunities for integrating more innovative techniques like value capture in the funding plan.

When considering the most appropriate financing sources, risk profile and cost are also important considerations.

The lowest cost financing source is usually the available revenues for the project, known as "pay-as-you-go." In terms of pure financing costs, general obligation tax-exempt bonds often have the lowest costs. While lower cost, the decision to issue such tax-exempt bonds needs to be weighed against the opportunity cost of utilizing the public's bonding capacity and leveraging its credit rating. Non-recourse tax-exempt and taxable revenue bonds, P3 financing, and non-recourse bank loans may be used instead, although they may have higher financing costs. In addition, some of these instruments, such as P3 financing, may leverage other cost-saving benefits, including specialized construction and operations expertise.

Innovative finance loans, such as the U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT) Build America Bureau's TIFIA and Railroad Rehabilitation and Improvement Financing (RRIF) loans, as well as SIB loans, can also offer rates and terms that are lower and more attractive than general obligation or non-recourse tax-exempt debt.

The development of a funding and financing plan is typically an iterative process, which during the early stages may involve several different options.

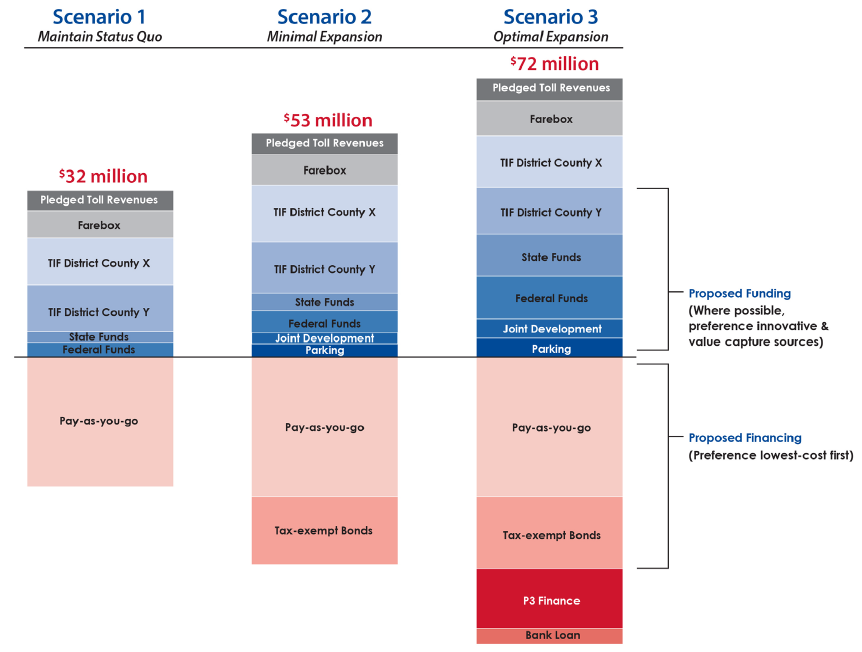

As Figure 3 shows, a financial plan that is developed at an earlier stage of project planning can include several different technical scopes based on levels of expansion and/or different mixes of funding sources and financing mechanisms. Later during the planning process, as the technical scope is confirmed and funding sources are committed, the financial plan will be confirmed. Practitioners should have qualified staff and/or outside advisors to assist with the development of the financial plan, to ensure that all possible options are being considered.

Financial plan for three different scenario. First, maintain status quo, with a $32 million budget. Second, minimal expansion, with a $53 million budget. Third, optional expansion, with a $72 million budget.

As mentioned, value capture may complement more traditional funding sources but is not a substitute. In addition, not all projects may be appropriate for value capture. This section provides considerations for practitioners assessing whether value capture techniques may be able to add value to their project. Chapter 3 provides further decision-making tools and considerations for selecting a value capture technique.

Value capture techniques may be appropriate when they can facilitate public policy objectives.

Value capture techniques differ in the extent to which they can meet different public policy objectives. Policy objectives related to promoting equity through beneficiary-pays models may be advanced through value capture techniques such as special assessment districts (SADs). Policy objectives related to addressing social inequalities through the creation of affordable housing may be met by including affordable housing requirements in respective plans or zoning ordinances that cover the project. Policy objectives related to improving the efficiency of land use in urban areas might favor joint development techniques such as air rights, which can involve the construction of residential or commercial developments above existing highways. Additionally, land value taxes might be appropriate when governments are already considering broader tax reforms. Examining public policy objectives may help practitioners narrow the range of appropriate value capture techniques for their project.

Examining the enabling legislation for value capture techniques can also help narrow the range of those that are applicable.

As further described in Chapters 4 through 9 of the Manual, most value capture techniques require enabling legislation. While a project is in the planning stages, practitioners should focus on value capture techniques for which enabling legislation is in place and for which legal hurdles can be overcome within a reasonable timeframe.

Value capture is more likely to succeed when considered early in the planning process.

Value capture techniques should ideally be considered early during project preparation, when changes to design and technical scope are still possible. Choosing to include value capture techniques during later stages risks making planning changes difficult to implement. This might result in less flexibility to optimize the integration of land use and transportation assets in order to maximize revenues from value capture. Although allowing for flexibility in design and planning is important, practitioners should ensure that the original economic rationale for the project is not compromised and that key public policy objectives, like purpose and need, continue to be met.

Expected community support will influence the success of a value capture technique.

For most value capture techniques, community support is critical. Business improvement districts (BIDs) are typically developed at the initiative of businesses. Special assessment districts (SADs) are often established based on a petition by property owners. When community members clearly support the use of value capture, it often is more likely to succeed. Value capture techniques such as TIF may compete for funding from existing public needs, such as schools and other government services, and therefore may be harder to implement. Practitioners are encouraged to involve stakeholders at the early design stages to obtain their input and address mitigation measures, where appropriate.

The geography of the planned project, including whether it is urban or rural, will likely impact value capture potential.

Some value capture techniques are more appropriate in densely populated urban areas. For example, air rights, in which a development is built above an existing highway, is most likely to succeed in urban areas where demand is high and land value justifies such a high-cost investment. Rural areas may benefit from other techniques, such as developer contributions, that are not as dependent on quickly rising property values.

Practitioners should consider whether value capture techniques could assist financing or plug a funding gap.

Assessing project funding and financing needs can also help practitioners determine where value capture techniques might fit within their funding plan. Some techniques provide revenue sources that can be dedicated to repaying financing. For example, if a transportation project is financed through general obligation bonds or loans from the TIFIA or RRIF programs, revenues from value capture may be used for repayment in certain circumstances. This provides a mechanism through which value capture can be used to finance construction cost obligations. Many techniques, however, require a "backstop" in order to obtain financing such as the issuance of bonds or obtaining bank loans. When this backstop relies on general obligation revenues or other revenue sources with high credit ratings, it reduces the extent to which financing is truly based on value capture risk.

Local match needs can provide a case for including value capture in the funding plan.

Value capture can be leveraged to meet local match requirements for Federal or State disbursements. Most value capture techniques can be used for this purpose, although those that result in revenues during the later stages of the project will still require a financing vehicle to make local matching funds available immediately. In Virginia, the Dulles Rail Transportation Improvement District used SAD funds to meet local match requirements needed to leverage Federal funds. In Texas, transportation reinvestment zone (TRZ) funds were also used to meet the local match. More information on these two cases is provided in the Appendix.

As discussed, value capture is rarely the sole project funding source, but is typically part of a funding and financing plan that includes several sources. Chapter 3 will help practitioners select one or more specific value capture techniques based on the characteristics of the transportation project.

13 Jake Varn and Sarah Kline, "How could "asset recycling" work in the United States?" Bipartisan Policy Center, June 8, 2017, bipartisanpolicy.org/blog/how-could-asset-recycling-work-in-the-united-states/.

14 "US 36 Express Lanes," Colorado Department of Transportation, www.codot.gov/projects/archived-project-sites/US36ExpressLanes.

15 "Federal-aid Matching Strategies," Federal Highway Administration, Center for Innovative Finance Support, www.fhwa.dot.gov/ipd/finance/tools_programs/federal_aid/matching_strategies/toll_credits.aspx.

16 Federal Highway Administration, Innovative Finance Quarterly, Fall 2005, www.fhwa.dot.gov/ipd/finance/resources/general/if_quarterly/fall_05.aspx.

17 Unless the sponsor provides a compelling justification for up to 49%. "TIFIA Credit Program Overview," U.S. Department of Transportation, www.transportation.gov/tifia/tifia-credit-program-overview.