List of Figures

List of Tables

This chapter describes how agencies can implement a funding and financing plan involving value capture techniques. It begins with an assessment of the universe of financing options available to an agency - if it chooses to use financing. It then covers the projection of value capture revenues, including sensitivity analyses to account for potential deviations from expected revenues. This is followed by the implementation of a plan to collect and utilize the revenues, which seeks to ensure they are spent appropriately. Finally, it describes the risks associated with value capture revenues and how these risks can be mitigated through thorough analysis, oversight mechanisms, and innovative financial planning.

Deciding whether or not to use financing - and, if so, the type of financing to apply - is a key step in implementing value capture. The types of financing available for a jurisdiction may also inform the types of value capture that may be appropriate for a project, as described in Chapter 2. The predictability of value capture-related cash flows varies based on project specifics, including size and mode, as well as the type of value capture technique applied. Many value capture techniques - for example, those involving incremental growth - by definition start out with a low revenue base that increases over the course of several years. Even value capture techniques that are less reliant on growth are still subject to real estate and other economic cycles and suffer from the fact that they are dependent on the success of one project, as opposed to a portfolio of projects. While the business and economic case, as described in Chapter 10, should give lenders a clear picture of revenue risks, value capture projects are still more difficult to finance than projects secured by more predictable sources, such as property, gas, or sales taxes. Sidebar 12 details the challenges associated with obtaining investment-grade credit ratings used in obtaining bonds and sometimes loans for projects using value capture techniques.

Despite this difficulty, many jurisdictions have found ways to finance value capture projects. For a project funded by value capture revenues to access the municipal bond market successfully, value capture revenues should be relatively predictable or their risk of unpredictability should be reduced. Value capture revenue risk can be reduced in several ways. In some cases, a jurisdiction may back a project with its full faith and credit in order to issue municipal bonds or receive loans at a low interest rate. In other cases, agencies may combine value capture revenues with other, more stable revenues in order to issue debt. Finally, agencies seeking to finance value capture may also consider alternative forms of financing from organizations with higher risk tolerance than municipal bond investors, such as from State Infrastructure Banks (SIBs) or from Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (TIFIA) loans. Agencies may also choose not to use any form of financing, but instead, may use their value capture revenues as they are collected - also known as pay-as-you-go funding.

Rating agencies, including Standard and Poor's (S&P), Moody's, Fitch Ratings, and Kroll Bond Rating Agency, play a critical role in the financing of value capture-related projects, such as those funded with special assessment districts (SADs) or tax increment monies. As financial intermediaries, they carry out extensive evaluation of the project, its risks, its sponsors, and other issues. Their rating may determine the cost of the financing (i.e., interest rate and other terms) and the ultimate ability of the financing to reach appropriate investors.

For the latter, the rating agency's designation of whether it is "investment grade" is critical. An investment grade rating is one in which the rating is above the level of "BB" for S&P/Fitch Ratings or "Ba" for Moody's (the three major credit rating agencies). Such a rating or higher (i.e., BBB, A, AA, or AAA on the S&P ratings scale) assumes "relatively low to moderate credit risk." 289 Many retail bond funds primarily purchase bonds that are rated investment grade. Since these bond funds dominate the tax-exempt market, a bond without an investment grade rating will be purchased by fewer investors, if any. Therefore, most public agencies strive to issue investment grade bonds.

While banks and private placement providers, such as insurance companies, are usually not required to follow this investment grade/non-investment grade framework, they often view investments in a similar way.

If the rating agencies determine that financing involving the value capture-related revenues will not receive an investment grade rating, project sponsors may revise the financial plan to make it more creditworthy through guarantees or backstops using high investment grade sources, such as fuel or sales taxes.

Once a financial plan including value capture has been outlined, as described in Chapter 2, an agency should move forward with a more thorough financial feasibility analysis to determine if its plan is implementable, and whether it can expect value capture to provide the needed revenues.

For example, to assess the financial feasibility of a TIF, an agency should start with the collection of key data that affect value capture revenues, including the following:

Financial feasibility for other value capture techniques will require similar or other analyses. For example, SADs require an analysis of the property market, sales tax districts require an approach centered on taxable sales, and transportation impact fees are determined by the number of trips assumed by new development and the associated cost of providing new transportation infrastructure.

Through this analysis, an agency can determine the expected revenue from value capture. Once the expected revenue has been assessed, agencies should then perform a sensitivity analysis to determine how revenues may vary based on changes to key variables. A well-executed sensitivity analysis can help determine the risk associated with value capture revenues, and therefore the types of financing that may be appropriate for a particular value capture approach. For example, a value capture transaction that is expected to have steady and low-risk cash flows may be able to raise funds through the bond market or receive loans from private banks. On the other hand, a value capture transaction with higher risk cash flows may have to rely on financing from less risk-averse lenders such as SIBs, or it can access the bond market and private banks through a credit guarantee from a public agency, as described in Sidebar 12. After determining the appropriate financing approach, an agency should then designate an entity to collect and disperse the value capture proceeds for eligible uses, as discussed in Section 13.3.

The mechanics of collecting value capture monies need to be settled before a value capture technique is applied, especially when financing is needed. With some techniques, such as SADs or TIF districts, the municipality should generally establish specific "ring-fenced" or "firewalled" accounts into which value capture monies flow. Monies from these accounts are authorized only for use specific purposes related to the transportation project to ensure that benefits are received by those paying and the required payments will not be deemed a tax.

With other techniques, value capture revenues can be paid immediately up-front or over a designated period. Naming rights payments are usually subject to a special agreement with a private company, sometimes negotiated by an advertising agency. For each technique, the process of collecting and depositing these monies is usually documented in legal agreements, drafted by legal counsel on behalf of the sponsoring municipality.

Managing the collection of value capture monies can be challenging because innovative ways of raising funds can create new challenges that jurisdictions may not anticipate. In El Paso, TX, it took more than 5 years after setting up the first TRZs for municipalities to address the issue that when larger properties within the zones were subdivided over time, the resulting smaller parcels were not automatically added to the TRZ funding register. Since then, they carefully monitor the parcel subdivision process to ensure that new properties are included. 290

Ring-fencing (i.e., safeguarding) accounts is especially important in cases where value capture monies are used to repay bonds or loans. Lenders conduct extensive due diligence on how the funds are collected, deposited, and used to repay debt service. Additionally, ring-fencing the accounts reassures the public that funds will be spent as promised. Some of the success in realizing the U.S. Highway 63 project was due to the establishment of the Highway 63 Transportation Corporation, as discussed in Appendix Section IX. It may also be required for a jurisdiction to qualify for Federal grants.

Value capture monies are used for purposes as dictated by statutes that determine how and where they should be expended. Generally, monies should be able to be used for eligible costs that make up typical highway or transit projects as defined by Federal, State, and local statutes, including the following:

In some cases, the value capture monies cannot directly fund the associated transportation project, but future extensions of the project and/or similar projects. This is common with impact fees, which are calculated to cover the expected future transportation required to serve a development type with a similar impact, such as a single-family home.

From the perspective of a local jurisdiction, another attraction of value capture monies is that they can count as a portion of a local entity's share in a project which receives Federal and/or State funding.

Jurisdictions should also establish a governance framework for value capture implementation that provides the various entities involved in a project with clear lines of responsibility throughout the project implementation process. Furthermore, agencies should engage stakeholders throughout the project life, not just during its planning stages.

Reporting and monitoring are also critical to ensure that value capture revenues are used appropriately and that projects are successfully meeting their goals. As such, an agency should create performance indicators and ensure clear responsibility for reporting the extent to which these performance indicators have been met and ensure that these results are published widely enough that the general public and key stakeholders are able to access them. As highlighted earlier in Example 14, the city of Chicago dealt with bad press over failing to properly publish how revenues from TIF were being used, so it established advisory boards to publish monitoring reports and better oversee them.

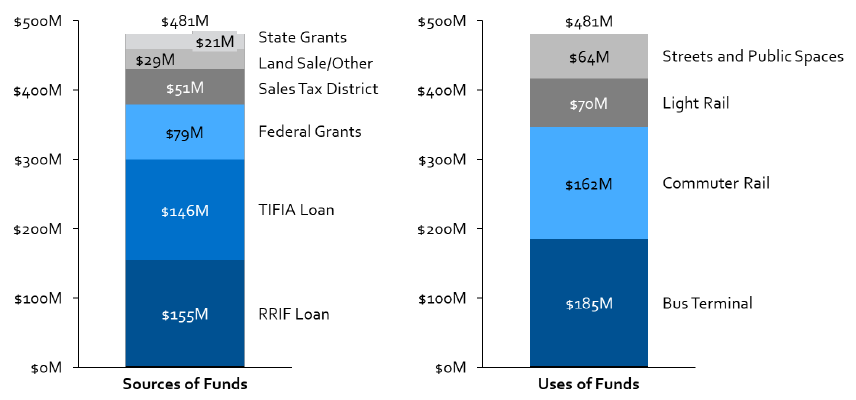

The Denver Union Station project illustrates how value capture funds can be combined with other funding in order to develop a funding and financing plan and mitigate the financial risks of value capture. Denver Union Station is a multimodal transportation project in Denver, CO, that includes an intermodal terminal, rail, and bus components, as well as street and public space improvements. The project was funded with traditional sources such as Federal grants and sales taxes. It also took advantage of innovative funding sources derived via value capture techniques, including SADs, TIF, and joint development. The project was also financed with TIFIA and RRIF loans. The breakdown of project sources and uses are described in Figure 9.

The Denver Union Station is a multimodal transportation project was funded with traditional sources such as Federal grants and sales taxes. It also took advantage of innovative funding sources derived via value capture techniques, including special assessment districts, tax increment finance and joint development, TIFIA and RRIF loans.

Sales Tax District

The Regional Transportation District, which provides bus and rail service to the Denver metro area, is funded through a sales tax of 0.4 cents that was approved in 2004; $51 million of funds already saved from this account were allocated to the Denver Union Station project. Additional funds from this sales tax district were pledged to the RRIF and TIFIA loans over several years.

TIFIA Loan and RRIF Loan 292 293

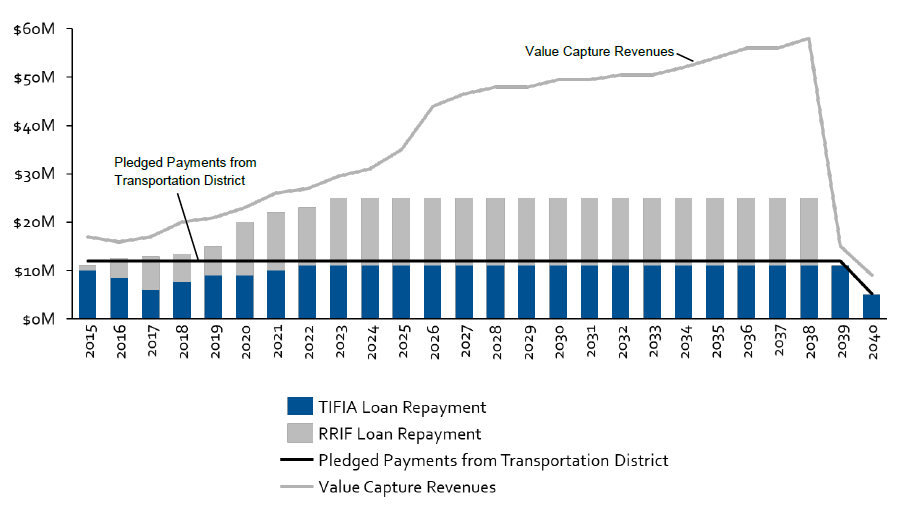

The Denver Union Station project could not be financed with tax-exempt municipal bonds, in part because most of the funds available for repayment were from value capture sources, which were perceived as less certain because of real estate risk and because financing was sought at the height of the 2007-2009 recession. However, the project was able to secure a TIFIA loan and a RRIF loan from the Federal Government. These loans were backed by pledged sales tax revenues, a relatively secure source of revenue, as well as more speculative value capture funding from a TIF district and a special tax district.

The TIFIA loan was structured as a senior loan and the RRIF loan as a subordinate loan. As seen in Figure 10, the project's pledged funding was significant enough to cover all TIFIA debt service payments in each project year, while the value capture revenues were projected to be many times higher than the debt service on the RRIF loan.

Because most of the pledged revenues would be used to make TIFIA payments, the Denver Union Station project had to include additional security guarantees for the RRIF loan in the event that value capture funds fell short of projections.

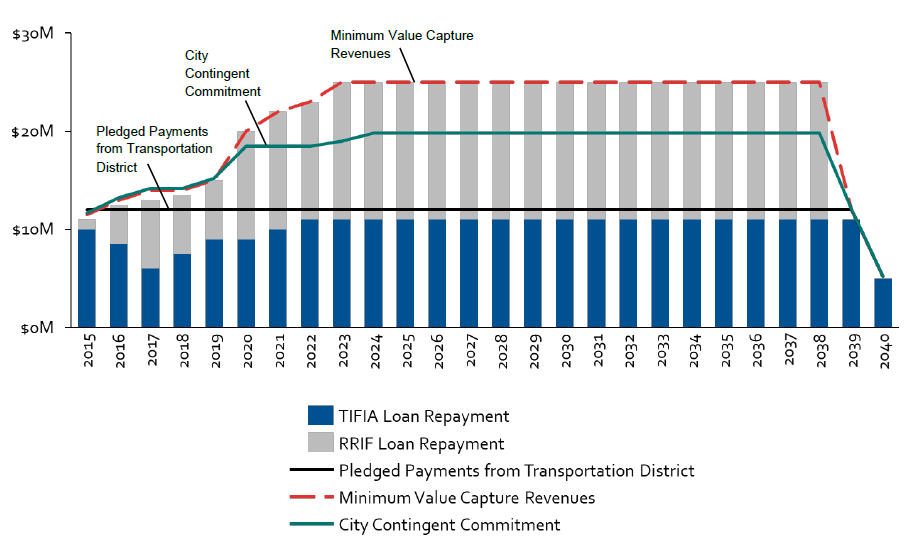

Because most of the pledged sales tax revenues would be used to make TIFIA payments, the value capture revenues were primarily the repayment source for the RRIF loan. The project had to include additional security guarantees for the RRIF loan in the event the value capture funds fell short of projections. As such, the city of Denver provided a contingent commitment, which guaranteed that in the event of a shortfall in revenue available for RRIF debt service that required a draw on the RRIF reserve fund, the city and county of Denver could request an appropriation from the Denver City Council of up to $8 million per year. This amount would cover approximately half of the debt service obligations. Figure 11 shows how this contingent commitment would work in the event that value capture revenues amounted to only 20 percent of their forecast. This contingent commitment, combined with a low likelihood of this extreme case, provided sufficient security for the provision of a RRIF loan.

The Denver Union Station case illustrates the benefits and uncertainty of value capture, and how this uncertainty can be mitigated through a mix of stable funding sources, contingent funding guarantees, and use of innovative and flexible financing.

289 Fitch Ratings, International Issuer and Credit Rating Scales, retrieved on 1/24/2016 from: www.fitchratings.com/site/definitions?context=5&context_ln=5&detail=507&detail_ln=500.

290 E-470 Public Highway Authority, 2016 Basic Financial Statements December 31, 2016 and 2015 (With Independent Auditors' Report Thereon), www.e-470.com/Documents/AboutUs/2016%20E-470%20Public%20Highway%20Authority%20Audited%20Financial%20Statement%20Report.pdf.

291 BATIC Institute: an AASHTO Center for Excellence, "Denver Union Station Area Redevelopment Project," Webinar Series: Innovations in Practice, Webinar 2, March 30, 2016.

292 Page et al., Guide to Value Capture Financing for Public Transportation Projects, 55-62.

293 Anastasia Khokhryakova, Financing of the Denver Union Station, Ballard Spahr LLP, 2013, www.law.du.edu/documents/rmlui/conference/powerpoints/2013/KhokhryakovaADUSCaseStudyFinancing-of-The-Denver-Union-Station-DMWEST-9630502-1.pdf.

294 BATIC Institute, "Denver Union Station Area Redevelopment Project."

295 BATIC Institute, "Denver Union Station Area Redevelopment Project."