Previous Chapter « Table of Contents » Next Chapter

This chapter identifies strategies that reach across all disciplines involved in roadside design. It focuses in detail on four of those disciplines: aesthetics, geotechnical (geotech), hydraulic design, and vegetation. Aesthetics is one that is typically thought of as an overarching objective within a project.

Sustainability solutions within the roadway cross-section, such as pavement materials, are not included in this guidebook nor are detailed solutions for bridges and other structures. Safety is considered an integrated component of all disciplines and is addressed within each.

Elements of the roadside aesthetic:

Aesthetics, more specifically the roadside aesthetic, is the physical presentation of landforms and the human built environment adjacent to a roadway. Within the context of transportation, aesthetics comprises the visual integration of transportation facilities into the surrounding physical and cultural landscape (Texas DOT, 2009). This relationship can be defined by multiple variables ranging from natural land forms and human-enhanced topography to the design of signage and road-safety elements.

State DOT examples of Aesthetic Guidance described in this guidebook include:

Landscape and Aesthetic Design Manual, Texas DOT (2009)

Pattern and Palette of Place,

Nevada DOT (2002)

Aesthetic Design Guidelines, Ohio DOT (2000)

To create an aesthetically pleasing roadside, a balance needs to be struck between the natural world and human-built forms, taking into account the needs of roadway users, the roadway owner, and the preservation or enhancement of the natural and cultural environment. It is important that aesthetics be linked to the functionality of the roadway. Sustainable and aesthetically pleasing roadways not only take into account the preservation of the natural environment but also the economic and social needs of stakeholders (Texas DOT, 2009).

With the growing focus on sustainability comes an emphasis on roadside beautification. Preserving and enhancing the natural environment through the designation of scenic by-ways, highlighting significant cultural resources and creating roadsides that are visually pleasing, has become increasingly important to a diversity of stakeholders (Schauman et al., 1992). As the majority of people interact with natural environments visually via their vehicles, the aesthetics of the roadway become their primary connection to this environment. This focus has not only led to the development of high-quality design elements at the roadside but has also contributed to the fiscal and environmental health of rural communities, enhanced and protected the natural environment, and promoted the importance of natural and historic resources (Figure 3-1). In response to this increased focus, federal and state agencies have begun to develop standards, procedures, and guidelines to address aesthetics of the roadway.

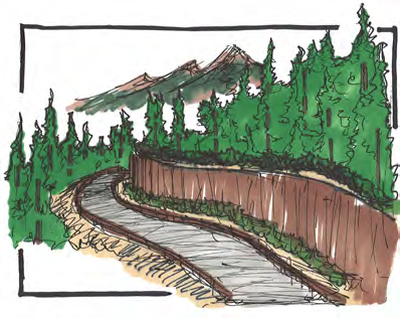

Figure 3-1: Rural roadsides that maximize views

Detailed regulations for roadside aesthetics are limited. FHWA Title 23, Section 109, of the Code of Federal Regulations requires that "aesthetic or scenic qualities of a place may be taken into account and preserved or enhanced" (Texas DOT, 2009). The FLH Project Design and Development Manual states that the most relevant aesthetics guidance and standards can be found within the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) and the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act (WSRA). The NHPA states that designers should work to identify historic elements at the roadside and consider options to minimize adverse effects, including "avoidance, rehabilitation, modified use, marketing and relocation" (NHPA, as amended, 2006). The WSRA of 1966 was implemented to protect rivers that present significant environmental, historic, and scientific value. When designing a road and roadside along a WSR-designated river, designers are required by law to protect the "aesthetic, scenic, historic, archeological, and scientific features" of the river (WSR, 1966). These two acts represent helpful guidance but only pertain to two components of the roadside (historic preservation and protection of rivers). The aesthetics discussion is much broader.

Typically, when roadway engineers begin a design project, the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials' (AASHTO) A Policy on Geometric Design of Highways and Streets, 2004 (known as the Green Book), is the first resource consulted. The Green Book outlines the design of roads and highways and provides national roadway design standards. Design guidelines within this guidebook are based on user safety and provide the minimum requirements when designing a road. Aesthetics are not a major focus within the Green Book, thus guidance concerning aesthetics is typically driven by the agency or owner of the roadway in question. On projects where agency guidance is not present, it is the responsibility of the roadway/roadside designer to champion sustainable and context-sensitive aesthetic principles.

Some state DOTs have developed statewide aesthetics guidelines. In their report titled Pattern and Palette of Place: A Landscape and Aesthetics Master Plan for the Nevada State Highway System, the Nevada DOT established a landscape and aesthetics program for the statewide highway system (Multiple Authors, 2002). The report states that context should be one of the most important factors in determining the aesthetic complexion of a roadside. Ohio DOT's Aesthetic Design Guidelines states that the primary goals of the guidelines are to promote a cohesive and uncluttered appearance; consider patterns, colors, textures and relief; and make aesthetics an inherent part of transportation projects. It states that interdisciplinary teams are a crucial part of the design process (Ohio DOT, 2000).

AESTHETICS

AND SAFETY

AESTHETICS

AND SAFETY

FHWA statistics indicate that vehicle collisions with trees account for more than 4,000 fatalities and 100,000 injuries each year (FHWA, Safety and Trees: The Delicate Balance, 2006). In some cases however, these amenities should be protected to preserve and protect the natural roadside aesthetic. Conversation should include the cost of moving the roadway, the aesthetic value of the hazard in question, and the importance of travel speed versus the value of the roadside aesthetic.

Roadside aesthetics is not a singular design problem. Each discipline and project may have varying goals and objectives. This section defines elements that comprise the rural roadside aesthetic and identifies trade-offs that need to be considered when working with other design disciplines to develop a sustainable roadside.

View larger version of Figure 3-2

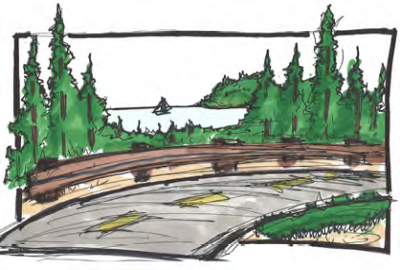

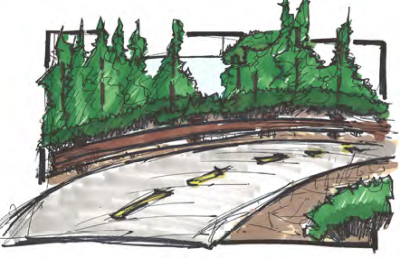

Figure 3-2: Roadway vewplanes Visualization showing a complete roadside view (at top) followed by the view with a highlighted foreground, middle ground, and background, respectively.

View larger version of Figure 3-3

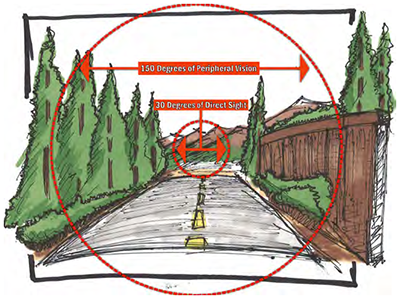

Figure 3-3: Drivers cone of vision at 55 mph

Figure 3-4: Decorative walls and lighting These add visual interest and help maximize views.

View larger version of Figure 3-5

View larger version of Figure 3-5

View larger version of Figure 3-5-2

View larger version of Figure 3-5-2

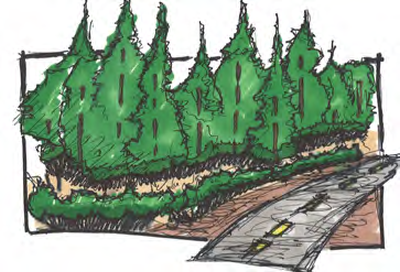

Figure 3-5: Trees framing views (top) and trees blocking views (bottom)

View larger version of Figure 3-6-1

View larger version of Figure 3-6-1

View larger version of Figure 3-6-2

View larger version of Figure 3-6-2

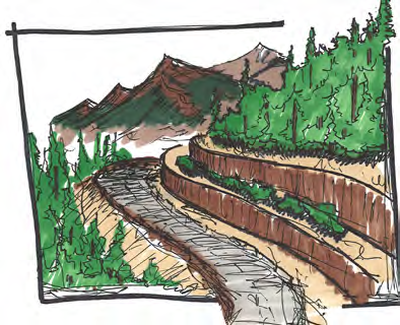

Figure 3-6: A wall detracting from views (left); a terraced wall with reduced scale to accentuate views (right)

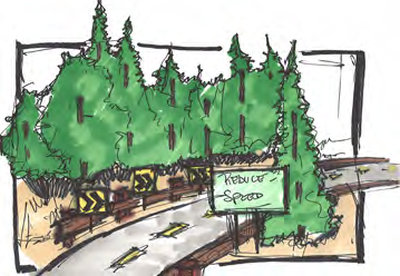

Figure 3-7: High quality and contextually appropriate signage

View larger version of Figure 3-8-1

View larger version of Figure 3-8-1

View larger version of Figure 3-8-2

View larger version of Figure 3-8-2

Figure 3-8: Retaining walls enhancing both safety and roadside character

View larger version of Figure 3-9-1

View larger version of Figure 3-9-1

Figure 3-9: Snow fence treatments

Development of a design approach that is flexible in its response to contextual conditions is imperative in creating specific aesthetic approaches that fit the geological, vegetative, social, and economic conditions of the roadway. This section outlines a suggested approach in developing and designing the aesthetic elements previously discussed.

"A basic sustainable landscape aesthetic for the roadside should include: well-proportioned and visually pleasing vertical built forms (bridges, monument and walls), well designed slopes and drainage swales, views from the highway to adjacent land uses and the preservation and enhancement of vistas and view planes to natural landforms."

(Nevada DOT, 2002)

Step 1: Corridor Principles and Visual Investigation

As with most planning and design processes, the initial scale of work should be at a high, corridor-based level. This area of study is usually defined by the limits of the given project.

However, in some instances, roadside aesthetic principles can be applied to specific historic, geologic, or specially defined regions.

The first step is to define the principles that the design should seek to achieve. Developing a broad "mission" statement at the onset of the project can help to focus detailed design solutions later in the project. In an effort to define the aesthetic principles of the corridor, a visual investigation of the corridor is helpful in understanding the context in which its aesthetics will be defined. An inventory of common features, unique attributes, and historical context can help guide the process. A visual presentation of these qualities can be created to help categorize and illustrate the current conditions of the roadside. These imaging studies can then be delivered to stakeholders in an effort to define the aesthetic principles of the roadway that interventions seek to create, maintain, and protect.

Case Study

I-70 CORRIDOR AESTHETIC PRINCIPLES

COLORADO

In an effort to develop a contextual aesthetic for the I-70 Mountain Corridor between Denver and Glenwood Springs, the Colorado DOT (CDOT) instituted the I-70 Mountain Corridor Context Sensitive Solutions (CSS) process. This intensive process included input and guidance from professionals representing a wide range of disciplines as well as multiple stakeholders who live and work along the corridor. Overarching corridor-wide principles included:

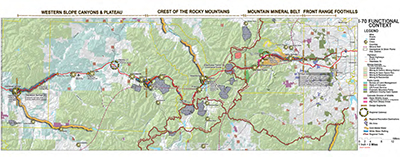

To streamline the process, CDOT divided the corridor into four zones to reflect the diverse aesthetics: the Western Slope Canyons and Plateau, the Crest of the Rocky Mountains, the Mountain Mineral Belt, and the Front Range Foothills. Specific aesthetic principles were then developed for each zone. Smaller sections were necessary to pinpoint more detailed locations and provide a base map in which to begin to apply aesthetic design solutions consistent with the principles.

Source: https://www.codot.gov/projects/contextsensitivesolutions

Step 2: Opportunities, Constraints, Weaknesses, and Strengths

Once the visioning process has been completed, the characteristics of the corridor need to be explored in depth. This process should define important elements along the corridor that aesthetic principles can help to enhance, buffer, or create. This process should occur at two scales: corridor-wide and more detailed sections of the corridor.

Corridor-wide Evaluation

A corridor-level view helps determine areas where sustainable aesthetic elements are best utilized and applied. Elements that should be highlighted include land use, population centers, lakes, rivers, open space facilities, and other natural and human-formed features (Figure 3-10). Once opportunities have been documented, designers can begin to define different design districts along the corridor. The aesthetic design of these districts should reflect the contextual environment of the area. Multiple contextual elements can be distinguished at this level of analysis, including:

Once this analysis is completed, application of various treatments can be explored.

View larger version of Figure 3-10

Figure 3-10: Example of corridor-wide evaluation

Step 3: Application of Treatments

This section gives an overview of various treatments and strategies to improve corridor aesthetics. These recommendations serve as a starting point. The selection of these will vary by project context and conditions.

Figure 3-11 : Options for preserving the clear zone

Figure 3-12: Retaining wall enhancing surrounding environment

View larger version of Figure 3-13

View larger version of Figure 3-13

Figure 3-13: Rock fall mitigation using shotcrete to prevent erosion

Case Study

ROCK FENCING ALONG I-70

IDAHO SPRINGS TO GEORGETOWN, COLORADO

One of the major design issues within the Idaho Springs to Georgetown segment of I-70 was the numerous rock fencing elements that existed above the roadway. These rock fencing elements prevented large boulders from falling onto the busy roadway along a section that in the past had been the site of rock/ vehicle accidents. While these safety elements were imperative to the safety of the traveler, they distracted from aesthetics of the sheer rock wall grandeur of the mountain side. In an effort to mitigate this visual impact, Colorado DOT experimented with different paint colors. A visual experiment was instituted using large paint chips carried onto the hill side by construction workers. Once the paint chips where placed next to the rock fences, observers from the roadway selected colors that most closely resembled the contextual geology of the site and the structural elements were painted that color.

This simple yet effective aesthetic study helped to develop a sustainable solution that met safety standards while minimizing visual impact. Simple aesthetic solutions such as this are both low cost and effective.

Photo Source: Colorado DOT

General